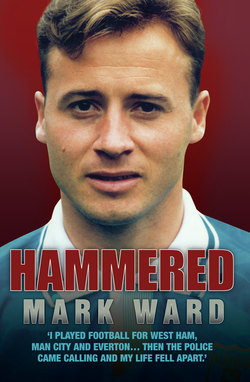

Читать книгу Hammered - I Played Football for West Ham, Man City and Everton… Then the Police Came Calling and My Life Fell Apart - Mark Ward - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. JOY AND SORROW

ОглавлениеHOW ironic that my first-ever appearance as a player at Goodison Park, on September 12, 1978, was largely thanks to … Merseyside Police!

The same constabulary whose officers arrested me in May 2005 were responsible for giving me and my team-mates at Whiston Cross (Juniors) the experience of a lifetime. Our local police force organised a five-a-side competition throughout Merseyside in the summer of ’78 – and the reward for reaching the finals was the opportunity to play at Goodison. It was a huge competition and winning it was no mean feat.

Our team comprised goalkeeper Kevin Hayes (‘The Egg’), skipper Peter McGuinness, hatchet man Carl Thomas and the two playmakers, Andy Elliot and myself. Andy was the best player at our rival school St Edmund Arrowsmith and we became good pals. The early rounds of the competition were played locally and we comfortably swept through the games and advanced to the semi-finals at the police training grounds in Mather Avenue.

Our journey by minibus to the semi-finals was one full of excitement and nervous expectation for our team of 15-year-olds. We’d all known each other from having played in school matches over the years and we were very confident of going all the way.

I travelled to the game in a pair of bright red Kickers boots that Mum had bought me. Nobody else around our way had them at the time and I thought of myself as a bit of a trend-setter. Dad was none too pleased to see his son strutting around in red boots but I was very much my own man even in those days. Just because my family are all Bluenoses, it didn’t deter me from wearing what I wanted – even if they were in the colours of our big Mersey rivals. In fact, I wore those boots until they fell off my feet and was forever gluing the soles back on them. This was the era of baggy jeans and I must have looked ridiculous.

My choice of music was different to that of my mates. I was influenced by my eldest sister Susan’s boyfriend at the time, Les Jones. He was into Earth Wind & Fire and I’d borrow his records and listen to this magnificent American R&B band. In later years I was lucky enough to see them perform live on two occasions.

I also loved listening to Elvis Presley. Not too many lads my age would admit to admiring Elvis but he really was the king in my eyes. One Christmas Mum bought me the Elvis Greatest Hits double album and I wish I had a pound for every time I played it. I’ll never forget the day Elvis died – August 16, 1977 – because I was at the FA’s coaching headquarters at Lilleshall having trials for England Schoolboys. I was there for a few days and I recall coming down for breakfast that morning, picking up a newspaper and reading the shock front-page headline ‘Elvis is Dead’.

Peter McGuinness and The Egg started to listen to Northern Soul and visited Wigan Casino, which was voted ‘Best Disco in the World’ by American music magazine Billboard in 1978 and was definitely the place to be seen. You had to be 16 to get in and, being five-feet nothing and baby-faced, I’d not plucked up the courage to try and sample the unbelievable atmosphere at this famous dance venue. I’d always thought it would be a wasted journey until my curiosity got the better of me one night and I jumped on the train for the short journey to Wigan.

I’d borrowed a blue velvet jacket from an older lad called Brian McNamara. As I stood in front of him and tried it on, he said: ‘It’s a bit big for you but you’ll get in – no problem.’ But looking back on it, I must have looked pathetic. Brian was a lot bigger than me and his jacket probably looked like an overcoat.

Stepping down from the train and walking to the dance venue, I started to have second thoughts. There was no way I looked 16. As we arrived I was amazed by the size of the queue – there seemed to be young girls and lads from all parts of England talking in different accents. I was in a gang of about 10 lads and as I neared the front of the queue, I was trying to remember my adopted false date of birth that would hopefully convince them that I really was old enough to be allowed in.

Just as I approached the entrance, a big bouncer tugged at my arm and pulled me to one side. ‘Sorry, son, you have to be 16 to get in here – not 12.’ I turned red with embarrassment, as everybody heard his humiliating put-down.

All the other lads entered the Casino okay, leaving me feeling gutted and alone outside. I was angry with myself for having believed that I might get in. I took off the oversized blue velvet jacket, tucked it under my arm and started the solitary journey back to Liverpool.

These knock-backs were very common at the time. My diminutive size and youthfulness made it very difficult for me to socialise with my mates of the same age. Another similar example occurred one night at Prescot Cables FC, where they held very popular Saturday dance nights in the bar area known as Cromwells. The disco was organised by the Orr brothers – Robbie and John – who also ran the football team. The venue was just up the road from where I lived and all the lads of my age were flocking there every weekend.

Peter McGuinness, who played for Prescot Cables, and The Egg were regulars and the stories they told of the girls they had pulled on their nights out there gave me the urge to join them. As I queued to get in, I was amazed by the quality of the local talent – the lads were bang on with their assessment. Standing between Peter and The Egg, I watched anxiously as Peter paid his 50p entry fee and as I went to give my coin to the bouncer, he said: ‘Sorry, no midgets tonight.’

With a lot of sniggering from way back in the queue, once again I felt totally humiliated at this rejection. Only this felt even worse than being turned away from Wigan Casino, because Cromwells was in my own back yard.

That night, Peter mentioned my problem to Robbie Orr, who said that if I approached him at the door the following week, he’d let me in. I didn’t really believe what Peter told me but there I was again the very next week, just hoping that Robbie would be on the door to let me in as promised. True to his word, after Peter introduced me to Robbie at the entrance, he just shook my hand and said ‘come in’. He never even charged me admission.

It turned out the Orr brothers were both Evertonians. This was the first instance of me being given special treatment simply due to my association with Everton. Ironically, although I never had to pay whenever I went back there again, Peter and The Egg both continued to have to fork out 50p every week!

At this time I’d been courting a girl from Whiston Higher Side school called Jane Spruce. She was two years younger than me and I was very keen on her. She wasn’t like the other girls her age – she was very confident and had an arrogance that attracted me to her.

Jane and her friends would also go to Cromwells on Saturdays. Although she wasn’t from a wealthy family, Jane’s parents, Barbara and George, worked hard for a living and ensured their daughter had the best in clothes. Always immaculately dressed, Jane was despised by some of the other local girls, which I put down to jealously. She was always the girl I fancied more than any other but she was no push-over and I soon realised that we were both strong characters. I was eventually to fall madly in love with her.

* * * *

The five-a-side tournament semi-finals at the police training grounds reached a dramatic finale. The whistle blew at full-time and then the cruel reality hit both teams – the golden chance to progress to the final at Goodison all came down to a penalty shoot-out.

Our manager Steve Hughes brought the lads together and told us not to worry about missing a penalty. In his eyes, we had already achieved great success just by getting this far.

I took our first penalty and slotted it comfortably home. Every penalty hit the back of the net, so it was left to the keepers to decide it. The Egg stepped up to take his and blasted it past their keeper. One last save from The Egg and we’d be in the final. Their keeper struck his spot kick very hard and straight but The Egg had his measure and turned the ball around the post. We all ran to Kevin, lifted him off the ground and the feeling was one of unbelievable elation.

On the way home in the minibus, Steve Hughes asked if any of us wanted a biscuit. But as he reached into his coat pocket, he suddenly laughed out loud. The digestives were no more. Steve had been so engrossed and stressed during the penalty shoot-out, he had crushed the whole packet of biscuits into tiny crumbs. The dream of stepping out onto the pitch at Everton meant as much to our manager as it did to his players.

Tuesday, September 12, 1978 was my swansong playing with my mates in the final of the Merseyside Police five-a-side competition at Goodison. That night was special and I remember scoring a couple of goals in a 4-1 victory. Everyone in our team played brilliantly and it was the last trophy I won with the lads I’d grown up with. Soon after, I was offered a contract by Everton and signed as an apprentice professional in 1979.

* * * *

Billy Ward was a very proud Dad when he left our house in Whiston to accompany me on the bus to sign the paperwork at Goodison. Dad had been a massive Evertonian all his life. He’d tell me about greats like the ‘Golden Vision’ Alex Young, Alan Ball and the other stars of the 1970 championship-winning side.

One of his big mates was Eddie Kavanagh, a legendary Evertonian who famously ran on to the Wembley pitch during the 1966 FA Cup final against Sheffield Wednesday and had to be wrestled to the ground by a number of coppers. They used to call Eddie ‘Tit Head’ because he took so many beatings in his time that one of the scars on his head looked like a nipple. Eddie ended up being a steward at Goodison.

I remember the look of pride and joy on Dad’s face as I signed my first Everton contract in front of Jim Greenwood, the club secretary. He was beaming – little was he to know that, just an hour later, our whole world would be turned upside down.

I’d been full of excitement on the return bus journey and couldn’t wait to get home and tell Mum what it was like behind the scenes at Goodison, to be part of the inner sanctum. But, strangely, when we arrived back at the house, she wasn’t there to greet us.

As Dad walked straight into the kitchen to put the kettle on, I noticed an envelope on top of the mantelpiece with ‘Billy’ written on it. I picked it up and gave it to Dad without even thinking – I assumed it was probably just a note from Mum to say that she had gone shopping.

As I sat in front of the telly, dreaming about the future … playing in front of massive crowds and scoring in the Merseyside derby … I felt a tap on the shoulder. With tears running down his face, Dad passed me the letter. And as I read Mum’s words, I realised the enormity of what she had written.

She was apologising for leaving him and their children. Dad and I looked at each other and we started to cry, not wanting to believe the terrible truth that the most important woman in both our lives had left us.

Dad adored Mum but, looking back on their time together, I don’t think she could cope with him anymore. The relationship between my parents was volatile at times, due mainly to Dad’s insane jealousy. It was a terrible disease of his mind and he couldn’t control it. He was never violent towards Mum but he constantly accused her of being disloyal when, in truth, she hardly went anywhere without him. I loved the pair of them dearly.

He was devastated by the break-up and, because of the hurt it caused him, I took Dad’s side. In fact, I never spoke to Mum again for 16 years.

But there was never any doubt that she loved her seven kids. Just six months after moving to Wolverhampton, she decided to return to Liverpool – with another man. Dad went crazy. I remember him screaming all sorts of threats one night after he’d found out she was living back in Liverpool with a new partner. He was making verbal threats to kill Mum’s boyfriend – and he meant it.

Even though I was just 16, Billy 15 and Tony 13, the next day we made a point of warning Mum’s boyfriend – I never did find out his name – to get out of town or else he’d definitely come to some serious harm. When we barged past Mum at her front door, her new partner sat there on the sofa. I just blurted it out: ‘Do yourself the biggest favour, mate. Get out of Liverpool before my father gets you.’

Mum was shouting and screaming but the three of us just walked straight past her and out through the front of the house, hoping we’d done enough to convince her new man to see sense. And thankfully he did. He moved out the next day and Mum followed him to start a new life together in the Wolverhampton area, where she still lives today.

Dad passed away in 1988, aged 52. It was a heart attack that killed him but I’ve always maintained that he really died of a broken heart, because he never got over losing Mum. I don’t blame her at all, though. That’s life, many couples divorce – I’ve been there myself – and if it hadn’t been for certain flaws in their relationship, who knows, they might still have been together today.

I’ll never forget, though, the stark contrast of emotions Dad felt on the day his eldest son signed for his beloved Everton. How, one minute, he was the proudest man in the whole of Liverpool and, just an hour later, he found out he’d lost the only woman he ever loved. Why she chose that day of all days to leave, I’ll never know. Mum told me years later that, with Dad out of the house and on his way to Goodison with me, she had an unexpected opportunity to leave. Feeling as desperate as she did at the time, she said it was a chance she simply had to take.

Her leaving the family home affected us all. My sisters, Susan, Irene and Ann, eventually set up home in Wolverhampton with Mum, while Billy, Tony, Andrew and myself stayed with Dad in Liverpool. From being a very close-knit family, the break-up of our parents also split us right down the middle. It knocked me for six at first.

Dad was a broken man but he cared about my future and gave me one bit of sensible advice: ‘Just concentrate on being a winner and give it your best shot at becoming a footballer,’ he told me. An old saying of his was: ‘Quitters never win and winners never quit.’ How right he was.

It was unbearable, at times, to hear him crying at night after coming home drunk from the pub again. I felt helpless, as most kids do when their parents split up. I think it did affect my football for a while but I was so determined to succeed in the game, I had to think of myself and try and forget about the troubles at home.