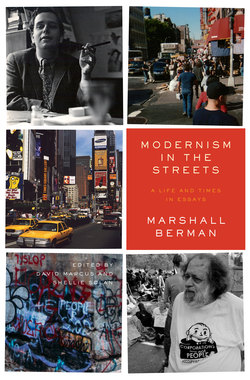

Читать книгу Modernism in the Streets - Marshall Berman - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Alienation, Community, Freedom

ОглавлениеIn his attempt to define an organic “structure of feeling” in nineteenth-century social thought, a structure capable of supporting the political Left and Right alike, Raymond Williams brings together much material that is of deepest interest to anyone who wants to rethink and refurbish socialist traditions.1 On the other hand, the very fact that he does bring such material together is a symptom of how dangerously vague and inchoate socialist traditions have become. In Williams’s view, the conservative-reactionary Wordsworth and the radical-revolutionary Blake, while pulling politically in opposite directions, are enveloped in a deeper, cultural unity of focus and insight: It is “the perception of alienation, even as a social fact, [which] can lead either way.” But to assimilate the Blakean “structure of feeling” to the Wordsworthian, even in such a limited way, seems to me misleading. A little scrutiny will show two sharply distinct perceptions in operation here, rooted in profoundly different systems of values; the covering term “alienation” only covers up their fundamental alienation from one another.

Consider, first of all, the passages cited by Williams in which “alienation” is supposedly expressed by Blake. Blake is lamenting the absence from the world of creative energy, spontaneity, exuberance, sexual expression, and sensual delight. These personal qualities are stifled by a social system shot through with political and religious, economic, and militaristic exploitation. What makes the city, London, so fearful a place is that it reveals the general exploitation (“the mind-forg’d manacles”) in such a diversity and profusion of forms: a different mark on every man. But Blake never rejects urban life in itself; it is only incidental to his picture of the modern world, a world essentially defined by repression and exploitation. The city of today is a vast exhibition hall for the “arts of death”; yet its dark Satanic mills will provide the foundation for that new Jerusalem, to be built with all the “arts of life,” in which Blake’s visions and prophecies of liberation will be fulfilled.

If we examine Wordsworth’s sense of alienation, as it is explicated by Williams from Book Seven of The Prelude, we will see how radically opposed to Blake’s his perceptions are. Wordsworth is undertaking here to describe London—for him, the epitome of the modern world—and his first, “alienated” reaction to it. We will notice, however, that for all Wordsworth finds to deplore in the city, his vision is marked by none of the poverty, squalor, privation, and slavery that Blake was so plagued by. (Granted, there is some vague generality about the city’s “low pursuits”; and the brief entrance of a beggar, who, however, is explicitly labeled as a symbol for Man and the Universe.) Not that Wordsworth is being callous: His vision of London is not really marked by anything else either. What is most striking about his response to the city—in contrast to his perennial response to the country, to nature—is its lack of concreteness. The doors of his perception are closed tight to what is actually going on in this place at this moment in historic time. The alibi he offers—that in fact nothing is going on around him, that here there are only “trivial objects, melted and reduced / To one identity”—only gives away the narrowness of his perception, the breakdown of his imagination. That he fails so dismally to grasp and evoke the contents of life in one particular city can be traced, I think, to his overriding and bitterly hostile preoccupation with the general form of urban life as such.

What is it about this urban life that upsets him so? The city is a mad rush, which, he feels, lays the “whole creative powers of man asleep.” It is a wild conglomeration of “self-destroying, transitory things” from which he seeks refuge in the “composure and ennobling Harmony,” which the vision of rural nature can provide. As a primary symbol for citification and its discontents, Wordsworth uses the Fair of St. Bartholomew, which he describes ironically:

The Wax-work, Clock-work, all the marvelous craft

Of modern Merlins, Wild Beasts, Puppet-shows,

All out-o’-the-way, far-fetch’d, perverted things,

All freaks of Nature, all Promethean thoughts

Of man.

In short, it is precisely those qualities which Blake saw as the noblest expressions of man’s “Promethean” freedom and power, and with which he felt most deeply at home—energy, exuberance, diversity—which Wordsworth finds most alien in the city; he despises them as “freaks of Nature” and “perverted things” because they alienate him from the stable peace and cosmic harmony he so deeply craves. Thus Wordsworth’s political and social authoritarianism is no accident: The structure of his feelings places him firmly within the metaphysical Party of Order.2 He perceives, more clearly than Blake did, the elective affinities between the spirit of urban life and that dreadful freedom he hates and fears; that is why he is so anxious to escape it.

Williams does not recognize the conflict of values I have pointed out. Nevertheless, I would judge from his general tone, both here and in his previous works, that if forced to choose he would opt for Wordsworth against Blake, for the Country against the Town, for that tradition in English social thought which exalts and aims to recapture “a medieval unity and innocence.” I am deeply disturbed by the structure of feeling that lies behind these preferences. Consider Williams’s own response to the city, which—going beyond Wordsworth, who had his reservations (which Williams mentions, but does not take seriously enough to understand)—is not so much a description, let alone an evocation, as a conceit. Thus he ascribes to city life “a new kind of display of the self: no longer individuality of the kind that is socially sustained, but singularity—the extravagance of display within the public emptiness.” Wordsworth’s judgment is cited, in tones of approval:

All the strife of singularity,

Lies to the ear, and lies to every sense.

A man’s life can evidently be “true,” that is, personally authentic, only with—in the context of a community—a small, homogeneous, face-to-face society, necessarily rural, in which his identity is clearly “recognized” (to use Hegel’s term) or (in Williams’s own formulation) “socially sustained.” Once this idyllic community is eclipsed, individuality becomes possible only as a desperate form of overcompensation, a defense against being totally engulfed, hence in some sense a fraud, a lie. I have a feeling Williams has been influenced in these persuasive formulations by the first part of Georg Simmel’s classic essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life.” I only wish, however, that he had been influenced by the second part of the essay as well, in which, after presenting the thesis above, Simmel brilliantly overwhelms it with its antithesis: that personality, insofar as it is “socially sustained” within a rural Gemeinschaft, is jammed into a stifling system of established roles, constricted and crushed into a stereotype; and that only by breaking the bonds of community, and floating freely in the fluid anonymity of urban life, can individuality find the room it needs to breathe and to grow. This latter possibility seems never even to cross Williams’s mind—yet it is the fundamental principle of modern liberalism, a liberalism which socialism claims not to abolish but to fulfill.

Again, as the litany of urban alienations runs on, we are told that “it is not only the ‘ballast of familiar life’ [Wordsworth’s phrase] that is lost, but also all that makes one’s own self human and known: the acting, thinking and speaking of man at once himself and in society.” Williams’s language here is depressingly loose; but if his terms “human” and “himself” and “in society” are not tautologies, the only meaning I can wring out of them is precisely “the ballast of familiar life”: the definition of oneself in terms of some role in the stable, static, perpetually “familiar” community. In an urban milieu, this possibility indeed tends to get lost (though not at all as fast, or as inexorably, as social thinkers used to think: Neighborhoods, it has recently been noticed, live on). And yet, on the other hand, since the French and Industrial revolutions, a more open, mobile, urban social life has generated new modes of self-definition, of “making one’s own self human and known”: By cutting loose from the ballast of one’s life, by soaring adventurously into the unfamiliar—in other words, by asserting one’s freedom. Blake, the most radical of Romantics and the most “modern,” demanded a total, anarchic freedom in aesthetic and political, sexual and moral life. Wordsworth, though politically conservative and authoritarian, nevertheless recognized and exalted this new freedom within a limited sphere: for the “highest minds,” in the realm of the poetic imagination. Whether Williams, with his expressed preference for an art nourished by communal impulse and suffused with communal culture and tradition, would concede even this much—or how, by his own standards, he would justify any sort of concession—is not at all clear.

In saying all this I do not mean to cast aspersions on Raymond Williams’s personal devotion to liberty, which I know is exemplary. But it is distressing to see where his sentimental need to enfold radicalism in the communal coziness of a Great Tradition has led him. Because he has resisted making sharp conceptual distinctions between the conflicting values, which any broad cultural tradition must contain, Williams has managed to avoid a clear moral choice. He has thus been drawn—unconsciously, perhaps, but steadily—into a style of social thought whose mixed indifference and hostility toward personal freedom have far less in common with socialism than with that populist mystique of “blood and soil,” which has expressed itself in such sinister forms in our day.

This essay was first published in Dissent, Winter 1965.