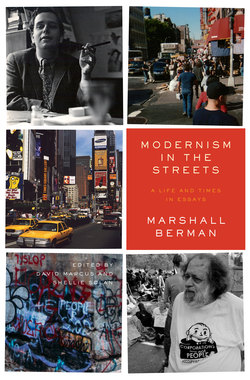

Читать книгу Modernism in the Streets - Marshall Berman - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Buildings Are Judgment, or “What Man Can Build”

ОглавлениеThe current fiction is that any overnight ersatz bagel and lox boardwalk merchant, any down to earth commentator or barfly, any busy housewife who gets her expertise from newspapers, TV, radio and telephone, is ipso facto endowed to plan in detail a huge metropolitan complex good for a century. In the absence of prompt decisions by experts, no work, no payrolls, no arts, no parks, no nothing will move.

Robert Moses, replying to Robert Caro, The Power Broker

I’ve had to save you. You are interrupting my plans now … Never mind. I’ll carry out my ideas yet—I will return. I’ll show you what can be done. You with your little peddling notions—you are interfering with me. I will return. I …

Mr. Kurtz, in Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls

and ate up their

brains and imagination?

Moloch, whose buildings are judgment!

Allen Ginsberg, ‘‘Howl’’

The political and cultural storms of the sixties enabled Americans to expand their minds in a great many marvelous ways. In some ways, though, our collective consciousness seems to have contracted and shrunk. For instance, it seems virtually impossible for Americans today to feel or even imagine the joy of building, the adventure and romance and heroism of construction. The very phrases sound bizarre; you probably wonder what’s the joke. Think of your gut response when you encounter something being built—a building, a road, a bridge or tunnel, a pylon or pipeline, a television tower, anything—your first impulse will almost certainly be to shrink back in fear and loathing. This impulse cuts across class, ethnic, generational, and ideological lines: Try it on your friends, your enemies, your parents, yourself; you can even try it on workers who depend on building for their bread and butter. It’s true, but not really relevant, that most of what’s going up today is both shoddy and brutal: Our recoil is too fast and too visceral to make discriminations; even on the rare occasions that something beautiful gets built, we cannot seem to see. We tend to think that everything around us must have been indescribably lovelier “before”—before it got “developed.” We idealize the past of our whole environment, the way Scott Fitzgerald idealized his primeval Long Island—“a fresh, green breast of the new world”—paradise, till Man came and ravaged and ruined it with his parking lots.

Our contempt for construction is so immediate and instinctive today that we hardly even notice it. In fact, however, it is relatively new; at least it is new as a cultural consensus, radically different from the consensus of a generation ago. Of course, it may not last, or it may turn out to be only an undertow rather than an overthrow. Still, we need to understand where it came from, how it happened, what it means. How have we come to condemn the process and products of construction as emblems of everything we find most destructive: massive ugliness, sordid venality, outrageous windfalls of wealth, endless storms of dirt and noise, big plans laying waste little people’s lives, organized viciousness without redeeming social value? How have millions of people who have never heard of Allen Ginsberg come to share his vehement judgment against the spirit “whose buildings are judgment”?

When I read Ginsberg’s Howl at the end of the fifties, his anguished vision of “Moloch, who entered my soul early” struck close to home. When Ginsberg asked who was the “sphinx of cement and aluminum,” the demon that devoured as it built, I felt at once that, even if the poet didn’t know it, Robert Moses was his man. For Robert Moses and his public works had a very personal resonance for me. He had come into my life just after my bar mitzvah, and helped bring my childhood to an end, when he rammed a highway through the heart of my neighborhood in the heart of the Bronx. When we had first heard about the Cross-Bronx Expressway, early in the fifties, nobody believed it, it seemed absurd, unreal. In the first place, hardly anyone I knew had a car: The neighborhood itself, and the subways leading downtown, defined the flow of our lives; the very idea of an expressway seemed to belong to some other world. Besides, even if the government needed a road, they surely couldn’t mean what the announcements seemed to say: that the road would be blasted directly through us—and, in fact, through a dozen solid and settled neighborhoods very like ours; that more than 60,000 people, working and lower-middle class, mostly Jews, but with many Irish, Italians, and blacks thrown in, would be thrown out of their homes. It couldn’t happen here, we thought: after all, this was our government, America, not Russia, right?

The Bronx of those days still basked in the afterglow of the New Deal: If we were really in trouble, we were sure our pantheon of liberal saints and heroes—Eleanor Roosevelt, Adlai Stevenson, Senator Lehman, Governor Harriman, our young reformist Mayor Wagner—would come through and take care of us in the end. And yet, before we knew it, trucks and cranes and immense machines were there, on top of us, and people were getting notice that they had better clear out fast, or else; they looked numbly at the wreckers, at the disappearing streets, at each other, and they went. Moses was coming through, and no political or spiritual power could protect the Bronx from him. For seven years, the center of the Bronx was pounded and blasted and smashed. When the dust of construction finally settled, and the exhaust fumes began to rise, our neighborhood was depopulated, economically depleted, emotionally shattered—as bad as the physical damage had been, the inner wounds were worse—and ripe for all the dreaded spirals of urban blight. Thus Moses gave me, and thousands of other New Yorkers, a crash course in the dynamics of power: what got built, and how, and for whose benefit, and what happened to the people who happened to be in the way. Moses was in the fullness of his power in those days.

Everywhere you looked, he was building something: A dozen expressways all over the state, slashed through the heart of the city and the country, leveling both; high-rise housing for literally hundreds of thousands of people, austerity barracks for the poor, opulent whited sepulchers for the richest of the rich; dozens of schools; a convention hall that loomed over Central Park; the biggest cultural center in the world at Lincoln Square; a new World’s Fair rising on the ruins of the old; Shea Stadium; at the mouth of New York Harbor, the city’s gateway, the world’s largest suspension bridge; far upstate, along the Canadian border, reaching a climax at Niagara Falls, the world’s greatest complex of dams and power plants. And all these projects were little more than beginnings for Moses, foundations on which to build more.

BIGGER THAN LIFE

What kind of man was this Moses? What made him tick? Where were the springs of his colossal energy and audacity, his monstrous pride and arrogance, his insatiable will to build up and tear down? I found myself obsessed with the man and his works. As I grew up and got a liberal education, my head filled up with a gallery of titanic builders and destroyers from literature and myth and history, in whose company Moses might belong; Gilgamesh; Ozymandias; Louis XIV, creator of Versailles; Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman, the enormous statue of Peter the Great that loomed over the Imperial Capital he had built, and that, generations after his death, menaced Petersburg’s citizens and drove them mad; Ibsen’s Master Builder; Baron Haussmann, who razed so much of medieval—and revolutionary—Paris and created the boulevards and vistas of our romantic dreams; Bugsy Siegel, master builder of the underworld, who created Las Vegas and was killed for it; “Kingfish” Huey Long; Mr. Kurtz; Citizen Kane. It was a strange but genuine Great Tradition. The paradigm that struck me most forcefully was Goethe’s Faust, that bible of the German bourgeoisie from which Moses sprang. Goethe’s Faust is an intellectual who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for superhuman powers, but who feels fulfilled only when he gains the power to build—to irrigate and develop an arid and barren coast, to make the wasteland bloom and open it to human life—and to murderously do away with the people in his way. It was hard to think about Robert Moses without mythicizing him: Like the immense hulks he built, he looked and felt bigger than life.

Moses himself was always glad to supply the public with archetypes in case our imaginations should run dry. He could come on like a great American gangster, racing around in fleets of black limousines, going out of his way to transgress speed limits, street lights, rules of the road, boasting that “Nothing I have ever done has been tinged with legality.” Or he could appear as an unreconstructed Soviet Commissar, proclaiming to the world that “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs!”1 He could even sound like the legendary oriental despots, serene in the totality of their power, free to let their magnificent malignity hang out. Thus, unlike most men of power, who characteristically use language as euphemism and smokescreen, Moses would bluntly say that “when you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax.” You could make no mistakes about that. But Moses could also mobilize self-images that were beneficent and benign. When he planned to turn the city dump in Flushing Meadows into an enormous park, he dressed himself as the prophet Isaiah and asserted Jehovah’s mandate to “give unto them beauty for ashes.” After his park was underway he would often say that he was the man who had seized Scott Fitzgerald’s Valley of Ashes—the ash heaps between Long Island and New York City, which became, in The Great Gatsby, a brilliant symbol of our civilization’s industrial waste and human hell—and transformed it into a symbol of natural beauty and human delight.

Over the years, I came across many New Yorkers who were as haunted by Moses as I was. We would watch his projects being built, trade rumors and references along with fantasies and myths. Where did his vast power come from? How had he begun? What demonic inner forces drove him on? There was one incredible story about what might be the Rosebud of this Citizen Moses. The rumor was that he had never learned to drive—and had taken his revenge by making himself Detroit’s man in New York and forcing everyone around him to drive everywhere. (I never believed it but The Power Broker discloses that the story was true after all.) What was he going to do next? We wracked our brains to anticipate his next move, before this Great Dirt Mover (as he liked to call himself) literally grabbed the ground out from under our feet. But he kept himself miles and years ahead of us, because we never learned how to “think big.” Could people be aroused to fight him? Was there any way he could be stopped? As the fifties ripened slowly into the sixties, we schemed and dreamed.

LOOKING FOR A MYTH