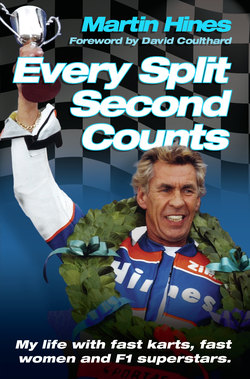

Читать книгу Every Split Second Counts - My Life with Fast Carts, Fast Women and F1 Superstars - Martin Hines - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Low-cc but High-Octane Fun

My first girlfriend was Pamela Rowland. I was twelve or thirteen at the time and, if I’m honest, it was more of a crush than a romance. I’m not even sure Pamela was ever aware we were an item. But she certainly sparked my interest and from then on there were a series of flirtations that saw me grow more confident and knowledgeable about the difference between the sexes and how much fun that difference can be.

My pulling power improved as soon as I was sixteen and got my first motorbike. Dad had started to sell 99cc Garelli bikes from Italy, which were very popular because you didn’t pay as much road tax on them. They looked fantastic with low handlebars, so you could tuck yourself down, making out you were riding a proper racing bike. With no helmets in those days it wasn’t too hard to cut a dashing figure that girls seemed to find attractive.

Garellis were surprisingly nippy. I remember leaving the bingo hall in a hurry one night because I was late to meet a girl I’d been chatting up. I opened up the throttle and about a mile down the road I became aware of a flashing blue light in my mirror. I pulled over to let them pass but they stopped too and accused me of speeding. When I told the copper my name and address, he said. ‘You’re a lucky lad. Your dad looks after our bikes so I’ll let you off with a warning this time, but don’t you ever let me catch you speeding again.’

There was little chance of that because two months later the bike was a write-off. I was in West Hendon, stuck behind a Rolls-Royce tootling along aristocratically in the middle of the road. As soon as we reached a straight stretch, I pulled out to go by him but, without any indication, the Roller swung across me to turn right. Oh, shit!

I’d read somewhere that with motorbikes it’s usually the machine that kills you, not the accident, and I had enough sense to drop the bike down, let go and get it out of the way. I hit the deck with a thud that shook me up but I escaped with a few grazes. The weight of the bike took it careering on under the car and it reappeared on the other side crushed and almost unrecognisable. If I’d hung on, that would have been my fate too.

That was the end of my motorcycling. I changed image and converted to a Mod. Out went the leather jacket, Chuck Berry and Brylcreem; in came the sharp Italian suits, trad jazz and a Vespa GS scooter with more mirrors than a Hollywood boudoir. But with Mods and Rockers deciding bank holidays were designed specifically for them to fight each other along seaside promenades, Dad decided I’d be safer giving up bikes altogether in case I felt the urge to join in. He tempted me with my first car, a Bond three-wheeler, which you were allowed to drive on a motorbike licence. In the hierarchy of production models following on from Lamborghini or Aston Martin, the Bond came a little below the Trotters’ Reliant Robin but I loved that car with a passion. Neither Mods nor Rockers would have reckoned it was cool, but at least you didn’t get wet when it rained and there was just about room to squeeze a girl in there with you.

After the Bond came a Ford Squire and a Triumph Herald, then my first car straight from the showroom, a dark-blue Vauxhall Viva HV, which I bought for £449. That was followed by a Sunbeam Stiletto and I’ve had a lot of cars since then, including E-type, BMW, a Lamborghini, two Porsches and my latest Merc E55 AMG. I got a kick out of most of them – but it’s difficult to think of any that has given me as much fun as that old green-and-cream Bond with its 197-9F Villiers two-stroke engine.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. Being a bit lairy, I fitted it with a Peco exhaust system that they used in motocross. It was perfect, giving the engine a deep, throaty roar so that, when I drove through Finchley, heads would turn thinking a Ferrari was coming. Sadly, I hadn’t realised that the fumes were no longer being taken underneath the car and out the back but were now seeping through the dash and building up inside the cab. I noticed that it smelled a bit but didn’t realise the full implications until I took my pal Johnny Burford out for a longer spin. We were cruising along happily until we passed out, overcome by carbon monoxide, and crashed into a hedge. We clambered out and spewed up all over the place. It was time for a rethink on the exhaust.

Johnny was also with me when we took the Bond sledging. We decided that a generous fall of snow would be the ideal conditions to take the car to the hill on Station Road and try a few handbrake turns. It was fantastic. We went spinning down the hill like something out of a mad-cap ice show. Until we hit the kerb. The Bond flipped over on to its roof and, from a car with rubber tyres, brakes and a steering wheel, it became a metal sledge, hurtling downhill with nothing to control it. As the friction started to wear away the roof, I could feel the top of my head becoming hotter and hotter. I was laughing because screaming would have been pointless, but I was also wondering what would happen when the roof finally wore away. Luckily, we came to a halt before we found out. We somehow scrambled out and I phoned Dad to come and help us.

It took five of us to get the Bond the right way up. Dad attached a tow line to his car. Unfortunately, the crash had done more damage than we’d realised and, when we stopped at traffic lights, I braked but nothing happened. The Bond slid elegantly into Dad’s rear bumper. We eventually got it to the repair shop, where the guy admitted it was the first time he’d been asked to fix a car where the main damage was that the roof had been worn thin.

With all this expense, it was a good thing I was starting to earn some money. I’d had an interest in movies ever since my childhood, when Signet Films, who had a studio in a basement round the corner from Dad’s shop, chose me as their juvenile lead in a couple of their productions. In the first I was the composer Handel as a small boy and was even allowed to pretend to play a harpsichord belonging to the Queen Mother. I was so brilliant in the role – or maybe it was because I was cheap – that I was selected to play the King of the Lilliputians in Gulliver’s Travels, which required me to sit on a throne and use my sceptre to prod people who looked about a tenth of my size thanks to some artful work with mirrors.

I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and, as I got older, I guess I thought I had what it took to be a movie star, if only a producer would spot my moody good looks and sheer animal magnetism. I felt I was perfect to become a cowboy or a chisel-jawed war hero. I loved war epics, especially when the Brits were particularly heroic as in The Bridge on the River Kwai or The Dam Busters. I also enjoyed gangster films with Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney, and action movies. My all-time favourite was Audie Murphy in To Hell and Back, in which he starred in his own heroic life story. (If there are any producers out there who want the rights to this book, I do have quite a lot of experience in front of cameras and I could do my own stunts!)

I was also interested in the technical side of films. I had a small cine camera and enjoyed making home movies, so thought it would be a good way to make a living, at least until I was ‘discovered’. I wasn’t sure how to go about it until Dad reminded me that Wally, who had now left the bike shop, worked in the transport department for Samuelson Film Services. The company was run by four brothers – Sydney, David, Neville and Michael Samuelson – and had started when, as a young TV cameraman, Sydney discovered the BBC would pay him £10 just to use his camera when he didn’t need it. A ten-week contract brought him a hundred quid and the brothers realised they had hit on a gap in the market. Samuelson’s became one of the biggest names in the industry, providing equipment for film and TV companies as well as making programmes of their own.

Wally explained there was a problem getting into the technical side of the business: you couldn’t get a job unless you were a member of the ACTT union and you couldn’t join the union unless you had a job. Fortunately, when he introduced me to the Samuelson brothers they took to me and said they would sort out the union card and I could work as an apprentice under Mr Vickers, one of the country’s leading camera technicians. This was a fantastic opportunity to learn a trade under the guidance of an expert. It was a rapidly growing industry that I was interested in and I would be with one of the top companies. Above all, it was the kind of hands-on, practical work that I enjoyed most.

My first serious assignment at Samuelson Film was to work on the hit TV show Candid Camera which trapped the public in hilarious situations. This was the first edition starring Jonathan Routh and one of those things that you never forget in life! One of the first programmes I worked on was when we took a Bubble car into a petrol station at Hendon Central to fill it up with fuel. They would normally take about two gallons but, unknown to the public and the garage staff, the car was just one big petrol tank with a Bubble body on it. The other classic I worked on was when goldfish were being eaten straight from the bowl. There were plenty of horrified faces from people who didn’t realise fish-shaped carrots were being consumed. Even with all this fun going on I still became restless and my dream job lasted less than a year.

I didn’t like working under someone and having him tell me what to do. It wasn’t Mr Vickers’s fault – he was fine to me – and I wasn’t being rebellious out of bloody-mindedness. I just came from a family that didn’t have a boss and it didn’t feel right. I needed to be my own boss and, by a stroke of great fortune, I was about to have the chance.