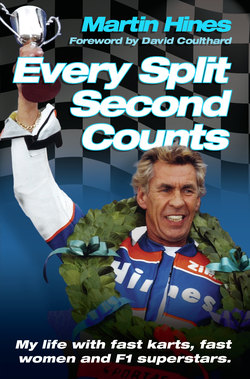

Читать книгу Every Split Second Counts - My Life with Fast Carts, Fast Women and F1 Superstars - Martin Hines - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 5

A Member of the Warren Street Boys

With kids now starting competitive racing at eight years old, it seems incredible that I was sixteen before I even sat in a kart. But you have to remember the sport was still in its infancy. The very first kart was built in 1956 by Art Ingels, a hot-rodder and racing-car builder in the States. He and some mates brought their karts with them when they were based in England with the US Air Force and within a few weeks it had started to catch on over here. It was more a hobby than an organised sport, an adrenaline rush for people like Wally Green, who turned to karting after he packed in speedway.

It was while we were watching Wally that Mum decided I could try karting and we bought our first TABs. Dad worked on them when we got back to the shop and was impressed with the quality. These weren’t toys: they were real little racing machines, albeit somewhat basic. He decided there could be a business in this growing craze. At the very least it might pay enough to cover the cost of our own karting, so we started buying and selling equipment and I had the chance to run the new company, imaginatively named Mart’s Karts.

One of my first jobs was to go and see Micky Flynn, a former American Air Force captain, who had remained in England after he was demobbed. He set up a company importing all those home comforts the Yanks who were still serving over here couldn’t buy in England, including karting gear from the big US companies such as Homelite and McCullochs. He was supposed to supply only the US bases but it wasn’t hard to persuade Micky to do a few deals for us too, just as long as we didn’t let on where we were getting the stuff.

Micky was one of the pioneers of kart racing in Europe and we had a series of ‘what a small world’ moments concerning him a few years ago. The first was when we spent a family Christmas in La Manga Club in Spain. Luke came back from an evening on the town and announced, ‘I was drinking with a girl who reckons you knew her grandfather. He helped start karting in England.’ Sure enough, she was Micky’s granddaughter. Some time later I was chatting to a guy in a bar over there who told me he had an affinity with karting because his grandfather had been involved and I was able to tell him, ‘Not only did I know your granddad, my son knows your sister!’ Eventually I met their mum, Micky’s daughter, and since then her husband and I have done a bit of business, so it’s gone full circle.

Dad always threw himself into every project wholeheartedly and quite soon Mart’s Karts wasn’t enough for him. He took on the lease at the Rye House track and within a few months had become chairman of the club. He decided this was going to be the HQ for our expanding kart business, so he and I knocked down the old wooden hut that stood near the track, dug out some foundations, mixed and laid the cement and erected a smart portable building to act as our new offices.

At first the business consisted mainly of selling bits and pieces off a trailer we used to tow behind the car to race meetings. At the time, most of the karts sold in this country came from two large manufacturers or were imported from Italy but that all changed when Dad got talking to a friend of his. Alec Bottoms was the plumbing half of building company Bottoms & Bartrup. He was also a motorsport enthusiast and he’d combined the two interests to produce a kart chassis he called the Zipper, which apparently was his nickname at school, though I don’t dare imagine why. It was agreed that I would race his Zipper Mark II chassis and it went well, so Dad suggested we should sell them from our shop.

We did OK with them, but Alec didn’t have time to build many himself, and, when he gave the job to a firm in Waltham Abbey, they too were slow in supplying us. Frustrated at losing sales, Dad approached Alec and persuaded him to sell us the jigs so we could take over the complete operation. Suddenly, Mart’s Karts was a major manufacturer. I wasn’t too keen on the name Zipper – although for a while we did use the slogan ‘There’s no flies on us, we’ve got a Zipper’ – but thought Zip had the right image, so we changed the name of the karts and decided it made sense to change the name of the company at the same time.

We worked on the karts, modifying them from my experiences as a driver, and they started to become very popular. The business grew rapidly and after a while we had to build a factory on a site I found on an industrial estate at Hoddesdon. That quickly became too small, so we found another plot of land just down the road and had plans drawn up for a bigger unit. Dad arranged for the design to be in two stages, with an extension that could be added whenever we needed it, but, just before building work started, I was chatting with the contractor and found out the extension would cost twice as much if we waited as it would if we had it all built at once. With the rate we were growing it made sense to me to go for it now, so I told him to go ahead. I forgot to tell Dad of my decision and, a few weeks after work had started, he went to have a look round and came back very excited.

‘The builders have made a mistake,’ he said. ‘They’re building the whole thing at once. We’re gonna get a bargain.’

I had to confess that I’d told them to go ahead, but he forgave me when he realised how much we would save in the long run.

I was excited about the business but, if I’m honest, at that stage it was more a way of earning enough money and creating the time so that I could drive. I had quickly realised there were two sorts of karting: one for the general public who just wanted to have some fun, and the other for a small, elite group of serious racers. I wanted to be in that set. They looked the part, they had the right overalls, the right kit and their karts went faster than others, including mine.

These boys were nearly all the sons of wealthy motor dealers and didn’t seem to do a lot of work, spending most of their time hanging around a second-hand car showroom in Warren Street. The leader of the pack was Bobby Day, whose dad, Alan, had the biggest Mercedes dealership in the country. Bobby had film-star looks and the attitude to go with them, and his mates weren’t too dusty, either. They included Mickey Allen; Bruno Ferrari, whose family connections meant he was never short of a bob or two; Buzz Ware, who earned his money making supermarket trolleys; and a lovable rogue, John J Ermelli. Buzz and Jon Jon were to become two of our first works drivers and we remain good friends to this day.

I knew I wasn’t as good in a kart as they were, but I reasoned that, like them, I had two arms, two legs, two eyes and certainly as much bottle, so there must be a way I could catch them up. I had one great advantage: I had plenty of access to Rye House and, even with my aptitude for mental arithmetic, I can’t begin to work out how many times I drove round that track, always trying to go a bit faster. It’s interesting that some people are drawn to karting because they are engine junkies, never happier than when they have a spanner in their hand, tinkering with this bit or that. Sometimes I feel they enjoy that more than the driving. I like fiddling with engines but the thing that has always given me the biggest buzz is to have my kart go faster than everyone else’s and, as the business progressed, I also wanted to sell more than the competition. Nothing gave me greater satisfaction than coming away from a meeting having driven the fastest lap of the day on one of our karts. Even when I lost a World Championship on the final lap one year, the disappointment was less because I’d driven the fastest lap.

I had a massive desire to succeed and, unlike some of the other kids who dropped by the wayside, I would not let myself be put off by setbacks. In those days I occasionally drove a gearbox kart with a 197-9F Villiers engine and, in one of my early races round Rye House, my engine blew when I was in second place. Back in the pits I realised the cylinder was going nowhere. Then I remembered that the trusty Bond had the same type of engine, so I worked frantically for the next hour and a half and transferred the Bond cylinder into the kart and raced it in the final. Unfortunately, that blew, too. I now had no kart and a car in bits and had to phone dad for a lift. We soon had both kart and car back in working condition and, despite the expense, he wasn’t at all upset that I’d blown two engines; in fact I think he was quietly proud that I’d shown some initiative.

I’ve never been much of a believer in the theory that some people are born with a steering wheel in their hand. I think the most important ingredient for success in motorsport – and in life – is what goes on in the six inches between your ears, or, for us bigheads, seven inches. Of course, it helps if you have some natural talent and it can be impossible if you have a handicap that means some things are just physically beyond you. But for most of us the key is having the drive and determination to put in the work it takes to succeed and to learn from our mistakes.

The best example I’ve ever seen is Ayrton Senna, who I first met in those early karting days. I’m convinced that, if Ayrton had decided to be a tennis player, he would have won Wimbledon; if he’d chosen golf, he would have shot 60 round St Andrews. I remember him flying model helicopters for relaxation but still his mastery of them was just incredible. He could have been brilliant at anything he decided to do, because he had that mindset. Second was failure to him and he made sure he covered every angle to ensure he would succeed.

I was determined I would become a top kart driver. I would find out what time the good drivers were testing and slip out behind them, following them round, checking which lines they took, where they braked and when they hit the power. Then I’d go out on my own and try to replicate what I’d learned, always looking to shave a fraction of a second off my previous best. Finally, I knew I was ready to take them on.

It took me a couple of years to start winning but I eventually found myself accepted by the in-crowd. At last I enjoyed a taste of their glamorous lifestyle, joining up with and driving against the Warren Street Boys and their young pretenders, who included Glen Beer, Dave Ferris, Trevor Waite and a couple of guys – Barry Cox and Dave Salamone – who even went on to star as Mini-Cooper S drivers in the original Italian Job movie with Michael Caine. They claimed they were cast because of their good looks but if that had been the case, surely I’d have been chosen!

The reality was that Dave was acting as chauffeur to actor Stanley Baker, who was one of the producers on the film, and Dave’s dad had a dealership, so was able to provide the Minis. After filming was over Dave offered me one of the cars – ‘just a few dents and scratches but only about a thousand miles on the clock’ – for £500. I turned him down and still have sleepless nights thinking about how much it would be worth now. Later, he offered me a BMW M11 with the M11 number plate. He wanted about fifteen grand for that and, again, I said no thanks, thus throwing away a potential profit today of around £485,000.

Fortunately, my driving was better than my eye for a bargain and people started to notice I was winning races. Eventually, I was chosen as one of the seven-man team to represent England in Belgium, which meant I could wear the coveted green helmet with the red, white and blue stripes down the middle. I couldn’t have been prouder.