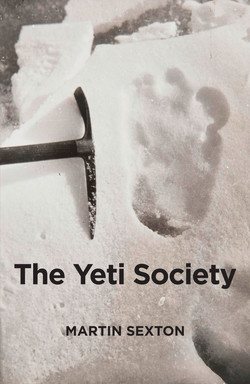

Читать книгу The Yeti Society - Martin Sexton - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE Mohammad went to the Mountain

ОглавлениеMohammad made the people believe he would call a mountain to him, and from the top of it he would offer up his prayers for the observers of his law. So the people assembled; Mohammad called to the Mountain to come to him—again and again, but the Mountain remained still and some of his followers muttered, but he remained unabashed and told his followers to remain patient and then a call came from the Mountain—but only he heard it—it seemed to say to him, ‘Come.’ So Mohammad stood up and declared he would go, and so he went to the Mountain.

‘The Holy Light watches over us.’ That is what Mr. Khan would say to me each time he held this old Quran in his hand. Mr. Khan was old, but no one was sure what his real age was. I lived with him in the Hunza in the north-west of Pakistan—the great mountain range was all around us, but few walked this path, only mountain goats and Taliban fighters. But it was another mountain thousands of miles away that was Jabal al Noor or the Holy Light, where the Prophet received his first revelation and this was the reason why Mr. Khan was here and why we had constructed the tunnels and it was why all the Qurans came from far and wide—from places I never knew or had visited. I would carry the old Qurans for Mr. Khan. We would place them inside the great complex of tunnels that ran for over a mile that lay cut into the rock buried beneath the earth like a fox's lair and black as a starless night. Outside was a standing stone the sun had washed white, that was taller than any man and some said was as old as the mountains themselves. Mr. Khan created the tunnels because God had told him so after his visit to the Holy Light in Mecca. In the revelation, he was told the day of judgement was coming and that he, Mr. Khan, must send out word to all the lands of the Prophet and beyond, that all the words of God in the Holy book that had been damaged by accident, fire or through mischief were to be sent to Mr. Khan. If he could he would repair and then make them whole and send them back out to the faithful. Those that were beyond repair he must bury in a mountain till the day of judgement itself.

He had created the tunnels by his own hand at first and everyone said it was a miracle. They had no supports or struts of any kind and one could stand up in them—not just a young boy, but also Mr. Khan, or any of the Taliban fighters that sometimes slept there. Some people would say the tunnels were as the word of God revealed to his Prophet.

Last summer the world shook. A—great earthquake had come and it seemed that it might kill us all. Some of the tunnels collapsed. The Qurans fell off their stacks and were buried. Even every loose sack I helped carefully fill with book after book had been swallowed whole by the Mountain.

But the great stone washed white by the sun remained upright, not even a faint crack was to be found. Mr. Khan said it was God's will and a sign the days were closer to the end because of the wicked and the Kafir and that our work must begin again in earnest as now throughout the lands of the Prophet many Qurans would have been damaged. He sent me out again to the villages—but this time the villagers were angry that I was there to collect broken books and had not offered to help them with anything else. This time they showed no respect and said that the old man was a fool and soon for his grave.

But elsewhere in other places far from the earthquake, other Qurans came, and not long after even the locals forgot their anger, remembered their faith and more books arrived. Sometimes very old Qurans like the one Mr. Khan carries with him arrive. Perhaps 100, 200 or even 400 years old—with beautiful calligraphy and some with the illumination of beautiful patterns and harmonies of wonderful shapes. I often get lost and drift away and study these wonders from the old world.

Most of the books of the Quaran are not so old. If they can be used again, we rebind and then reuse and send them back into the villages and mosques. We only place those that are beyond binding—with fallen loose pages, or those with pages missing, or those with whole parts missing, burnt, stained or torn, with just the fragments of the holy words of God—in the sacks and then place them deep inside the tunnel complex. Sometimes large groups of children my age—some younger, some older—walk on a pilgrimage from the madrasas just to see Mr. Khan's cave of Qurans. I am not sure how many books are here—in whole or part. Mr. Khan says we have 1,000 sacks or more and each full sack I know is itself filled with millions of holy words.

My father told me before he went away to fight with the Mujahideen against the Russians and never came back that he and his father and his father before were descendants of the conquered as well as the followers of the Great King Alexander when he crossed the mountains into Indus. In addition we had the formidable fighting blood of the Khalsa, our ancestors were the initiated Sikhs, but that we also had Mughal relations. He would take me to the odd rock carvings that lay beside the path Alexander's men came by and the world conqueror himself trod. Some carved in Sanskrit left by the Old Kingdom of Tibet when it invaded China and the Indus in the 7th century, but my father said it was much older and that even Alexander saw it. Some of the rocks had giant hairy men and no necks with long extended arms waving, carved into them. One was over two metres high.

The day before he left he sat me and my sister by the rocks and told us of the old world and that where we lived men always fought and this had been the way before even the Holy book and was still the way, but maybe Allah could stop it. He stood up beside the great carved giant and told me that when Alexander crossed into Asia and the Indus, he came across a group of sages who did not bow but stomped their feet by that very rock. One of the sages said to Alexander:

‘King Alexander, every man can possess only so much of the earth's surface as this we are standing on and you are mortal like the rest of us, even though you covet and ache for much, much more. You will soon be dead and you will own no more of this earth than that is sufficient to bury your bones.’

Alexander could have killed him on the spot, said my father, but he knew the sage was truly free and spoke the truth and it was then the great Alexander knew he would not return home. My sister and I myself knew our father was talking about himself and we wept. Then our father took our hands and said that we must recite the Throne Verse, as he did, to enter the protection and security of Allah each evening, before we slept or set out on any journey. Then with our final words together, we all recited in unison: ‘His throne includeth the heavens and the earth, and He is never weary of preserving them. He is the Sublime, the Tremendous.’

I like old books, old things and manuscripts. My mother and father have a gift for languages. I can put cultured Urdu into good English, I can speak highly colloquial Urdu, Arabic, count in Uzbek, use Punjabi, Braj Bhasha, some Persian, Sanskrit, Brushuski common words. My sister says I also like to swear in English. I went to the Aga Khan middle school and because my father was respected I sometimes stayed in the castle or Baltit Fort in the Hunza Valley by the white-capped mountains. One day my father's teacher let me hold and look at a manuscript that he said was the oldest in the world and told the most ancient of folk tales, the Jataka Tales. He would recite The Story of the Great Ape, how the wisest of men, the first man was once born as a great ape and lived as a recluse amidst the forests of the hidden valleys of the Himalaya.

I have a secret. In the Qurans that are sent—sometimes, old postcards or photographs or drawings fall out, with beautiful pictures of far-flung places. Strange cities, great buildings, people dressed in all manner of clothes, even women with painted faces who show their bodies, animals I have never seen. Some of these I keep and look at when Mr. Khan is sleeping. One day as I was sorting through the books an illustration fell out from the pages between the torn bindings, and I read the half-erased title ‘…tin in Tibet’. It had a young boy like me with a small white dog. He was on a mountain just like the mountains that we hide the books in. A great beast stood up in it, not a bear, but bigger than the tallest man, full of hair, as tall as the great stone outside the cave and like the rock carvings my father showed me. I examined the illustrated mountains and looked again at the strange animal and then gazed hard into the high mountain range all about me and wondered could such a beast live here? It excited me and I became more certain every day that indeed it did. The mountain was not named in these two loose pages but I could just barely read the torn and fuzzy worn type that it was in a place called Tibet and that the boy was called Tin and if the boy Tin could go, so could I. My English was good. I knew this place existed as my father allowed my sister and I to pore over the English atlas our mother had hidden. I knew that the mountains here and about met, and these mountains were linked by valleys and plains and other ranges that made the roof of the world—linking India, Nepal, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bhutan and Tibet. My father was a good fighter and joined the Mujahideen fighting the Russians. He was promised new weapons and money for our family by an American who said as tribal leader if he brought some of the other good fighters along, we would no longer be poor. My father said we were all descended from the great fighters of Huzan who were descendants of the men who followed Alexander the Great. His campaign historian recorded that he saw a tribe of such beings as those carved on the great stones once from his ships, as they navigated into a long river into the Indus and that his men shot arrows at them and Alexander ordered his men to swim to them and catch one but they all fled into the trees; that he had even asked the locals to bring one to him, but they said they could not be caught like other animals. All this would play over and over in my mind. I became lost in this more than anything else each time I gazed at these two faded pages of ‘…tin in Tibet’.

One morning I awoke determined. I decided that I would go to the mountains. I would leave the old man and the caves and head higher into the range. I would even join the fighters and help them carry their guns and packs if need be; just so I could in turn leave them and find this hairy man of the mountains and the lost tribe Alexander the Great spoke of. Maybe I would find my father too. I, Mohammed, would find the Yeti and do all this and one day they would tell stories of me.