Читать книгу The Yeti Society - Martin Sexton - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

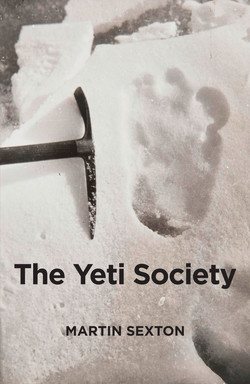

CHAPTER THREE Eve at Bluff Creek

ОглавлениеBigfoot is real. Absolutely breathes, eats, mates, lives, and they are our brothers and sisters, they are not animals, they are human beings with a soul, just as all humans have.

—Red Elk, of the Blackfoot and Shoshoni Nations

‘Bigfoot is the white man's name, the locals call it See'atko, Skookum, Oh Mah, Sasquatch—but there are as many names for it as there are indigenous tribes of our ancient lands they call North America and these names have been here as long as we have had stories to tell of them, a thousand years and more before the invaders came. That's what Snowstorm, medicine woman of the Karuk peoples told me and I can tell you, if it is a hoax, it is a hoax like no other, and if it is real, it changes everything; either way it is beautiful, real or not.’

That is what Ross said each time he spoke of the scratchy faded colour film. He was a scientist and as rational as they come. He declared himself a sceptic, a believer in nothing. Ross did not even believe his own eyes, having seen an animal up by a creek on the Kalmuth River. It stood up, its back to him, then stepped—he said he thought he saw it take at least one to two steps forward—then it was down on all fours into the woods, disappeared from sight almost immediately. It looked odd, but he then managed to convince himself later it was a bear. But he knew being alone in the woods, amongst bear, coyote, mountain lion and deer, the sound of owls and unidentified bird call, one could easily listen too much to one's own power of suggestion. Sometimes things looked odd in the wilderness. People themselves also became odd, alone in such wild places. Even though Ross was a sceptic he talked endlessly of this film.

The film baffled him. I had never seen it, only heard him talk of it. Though a scientist, he would talk of it like a disciple would of a religious event, a miracle.

One day we heard something at a high elevation, a powerful ape-like whoop, up above the treeline in the high mountain, then a crashing through, into the woods below. The ground shook under the great weight of this something that seemed to be walking on feet, not hoofs or pads and claws, but heavy steps separated out in what seemed like giant strides down a precipitous side of the mountain. Yet we saw nothing. We had only the long list of all that was actually real in the forest and on the mountain, that we turned over and over again in our minds and in our conversation, in order to stop our imaginations running riot. I knew that once we got back to the cabin, I would go to the town and see the film that Ross kept talking about. Shot in 1967 here in Bluff Creek, just 20 miles from where we heard the commotion and where we slept uneasily that night. As we drove back down the old logging road in the truck, the radio was playing the song ‘A Girl Like You’.

Ross's cousin Ruth lived in the town and had an old projector that she used to show Bible Class films to the children at the local church. At real expense, Ross had managed to obtain a print of the original stock film and he said it would be the first thing we did once we hit town.

Ruth was an attractive, middle-aged woman. Even though she was five years older than me, she had this innocent look about her. She wore no make-up and was confident in her skin. She was a Southern Baptist who had not shaken her religious upbringing. To find the film, we had to go through boxes of Bibles, books on theology and numerous old prints of religious events from the Old and New Testaments. Those not in boxes or in piles on the floor were on the walls in frames or pinned or in rolls on the mantelpiece. I saw the furniture of Ruth's mind before I met Ruth. And if there was any doubt, we had arrived early evening and Eric said she would be out at church.

Every picture on her wall was religious—but with mountains. Jesus and the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus in the desert mountains casting down Satan, Moses getting the tablets on Mount Sinai, Moses seeing the Burning Bush on the sacred Bedouin Mountain—then one that missed my Sunday school education—Ross had to explain it was Aaron being buried or taken up on a mountain in Jordan. He told me, even though, like me, he did not believe in God, that it was best to be respectful to Ruth, not just because we were guests that evening, but because she had been through a lot and this was how she dealt with it.

I was drawn to a particular picture, a print of an etching. It depicted a vast Jordanian desert down to the Red Sea with large mountains all around. Moses stood before his priest—a horizontal Aaron, with his hands held up to the sky, rays emerging from broken clouds. For some reason the picture gave me a feeling of vertigo, a feeling that had strangely escaped me from the real mountains we had just left, but was unexpectedly and dizzily present on this imagined range.

Grouped together, I was struck by how many apocryphal religious events happen in mountains. My mind returned to what we had heard and felt the night before. I was suddenly reminded and excited to see Ross’ film. The controversial 1967 short film, the Patterson-Gimlin film. A cowboy, Bob Gimlin and an adventurer and self-confessed Bigfoot hunter, Roger Patterson, went looking for the beast of the woods and mountains, an unlikely search for what the local tribes call Oh Mah or Sasquatch, the boss of the mountains and then…they found him.

Except the him was a her. It was clearly a female, all hair and mammary glands. Its breasts, along with its heavily muscled thighs, moved with gravity and an hallucinatory clarity through the very few seconds of the shaken film amongst the flood damage of the Klamath River in Bluff Creek. The beast was not hidden, obscured by vegetation, a notorious blob Squatch. It was in plain sight, on a clear sun-drenched afternoon. One had one simple conclusion to draw—either it was a very large man in an ape-like suit or it was real. It was a binary choice. There was no in-between.

I lost count of how many times we screened that film, over and over again that night. We watched, largely silent, our only words being, occasionally…Shall we look at it again? One more time, yes? And so we did…Again and again. It looked strange. My eyes were at war with my brain and then vice versa as both would jump from opposing conclusions. The repeated screenings did not help matters, one set of eyeballs convinced one it was real and another viewing did not add clarity but left the same set rejecting the previous conviction. Eric was right, if it was a hoax it was a work of genius and if it was real…well…

Then Ruth walked in. We were so engrossed we did not hear her, even though the film is entirely silent. She switched the lights on and the first words I heard her say were, ‘You watching Eve again, Ross?’ I stood up to clumsily greet her but she ignored me and walked to the kitchen. She continued, ‘That's naked Eve. God sent her to show us we have to begin again. Judgement day is coming. Who's your friend? I have only got basics from the store, if you want eating.’

The next morning I set about finding out as much as I could on the background of the Bluff Creek film, of the strange hairy bipedal figure that had Ross and myself second guessing every time we watched it. His obsession had infected me. Unknowingly I found myself entering a world of clashing European empires and the mountains of the word. Nearly two decades before the Bluff Creek film, I found out that a world away, on the Nepalese side of the vast Himalaya, two highly respected English mountaineers had discovered inexplicable tracks. Eric Shipton along with a Dr Michael Ward were shocked on their descent down the Melung Chu, unroped but still on a dangerous uncharted climb close together, to find on a desolate glacier at an elevation of 16,000ft a long trackway in virgin snow. Despite the snow combined with hardened ice, deep depressions of large and bare, unadorned bipedal hominoid footprints were in a long run. As they were the first humans to chart this unexplored area, and at such an altitude to find anything, any animal was uncanny. They pondered could it be another climber? But surely only correctly equipped mountaineers with appropriate footwear, indeed any footwear would have made some sense. Truly baffled they took some photographs of what they found. Having no means to accurately measure the individual footprints, Shipton took what would become two iconic photographs that would stun and shock the world. One with Ward's boot for scale beside it and, the most iconic of all, one with Ward's ice axe beside it. What is more, two other equally respected mountaineers on the same expedition, including a scientist, Bourdillon, had followed them a day later over the Menlung La and come across the same trackway. Equally baffled, they followed it for over 3 miles before they had to turn back. When they returned to the high elevation base camp they met with the highly respected and experienced Sherpa Sen Tensing (who would later, along with Edmund Hillary, be the first to reach the summit of Everest). His local knowledge, having been raised and lived near and on the mountains, gave him no doubt. He confirmed they were footprints of a Yeti. The extraordinary photographs and the back story of how they came across them began in 1951 when Ward, a doctor with the Royal Army Medical Corps, came across some hidden photographs of the unexplored Nepalese south side of Everest taken by an RAF Mosquito X1X. The photographs revealed some key features critical to any ascent of the highest mountain in the world from the Nepalese side.

Two years earlier all foreigners were barred from entering Nepal and all Everest expeditions had to take place from the Tibet side. Along with these critical aerial photographs, he unearthed a rare and forgotten photogrammetric survey from the 1930s. Ward felt he had found the means for a successful ascent of Everest from Nepal. His attempts at getting such an ascent going with help from the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club proved difficult, not least because his plan meant a crossing of the treacherous Khumbu Icefalls and its maze of cliffs and shifting deadly crevasses. Ward managed to convince two New Zealanders, including Hillary, to join him along with Englishman Eric Shipton. When they finally arrived in Nepal and climbed the 18,000ft to the icefall, Ward described it as,

’…a glimpse into purgatory, the icefall had become an immense, unstable ruin, as though an earthquake had shaken the entire glacier.’

Nepal lies on a major fault-line between two tectonic plates. One has the continent of India resting upon it and pushes east and north at a rate of 2cm a year against the other, which carries Asia and Europe: it is the very process that created the vast Himalaya mountain range.

It was this expedition, and towards its end, as they were exploring the south-west of Everest in the Gauri Sankar at an elevation of 16,000ft on the glacier of the Mending basin, that Eric Shipton and Dr Ward found the tracks. Sherpa guide Sen Tensing had no doubt that what they first saw and photographed was a Yeti. At this altitude and in such a remote place on earth, the prints were fresh, they could only have been made that day or the night before, possibly very late the previous day. Shipton and Ward followed the tracks for a mile but the heavy loads they were carrying and the altitude and the pressing reminder as to what was their actual task, researching an ascent of Everest, caused them reluctantly to abandon the tracking. I found that many other respected mountaineers, both before and since Shiptons's photographs, had seen footprints at impossible elevations. As far back as 1925 the geologist N.A. Tombazi witnessed a naked, hairy man at a distance in Tibet, on the Himalaya, and went to investigate the area. He saw the clear bipedal prints left behind. Tombazi, the leader of the 1925 British Geological Expedition, was convinced he had witnessed a Yeti.

He saw it, spoke about it and then wrote about it. They all thought he was mistaken, but Reinhold Messner thought, ‘I know the high mountains and I can name every animal on the mountain, and in the valleys below and the great high plateaus.’ And just maybe Messner could. After all, Reinhold Messner had climbed Everest. He was a great mountaineer, maybe the greatest. Reinhold with his partner Peter Habeler had been the first to ascend to the very top of Everest without supplemental oxygen. Indeed, Messner had conquered all the highest mountains on earth, fourteen of them, and all over 26,000ft without supplemental oxygen and frequently on his own for the greater part of the final ascent. But this was what his detractors used against him. Mountain men are competitive and could not stand Reinhold's success or, worse, the attention it got him. So they said he was mistaken. All that climbing without supplemental oxygen had given him anoxia or brain damage and made him unreliable. Not only had a lack of oxygen damaged his cognitive functions, but bizarrely and conversely, he had compensated by sucking up all the oxygen of publicity for their achievements and if that was not enough, he wanted more of the spotlight for his ridiculous claims. The criticism was sharp and was designed to unnerve him. Reinhold was not just disliked for his success, for many years before he was equally and more devastatingly loathed for his perceived failures.

A personal tragedy took place on a mountain, one which directly hurt him and his family, so it was even stranger that the death of his younger brother led to him being despised in his grief for something that had a lesser impact on others.

If Reinhold thought he could finally leave his detractors behind him atop the highest mountains in the world, on isolated peaks away from civilisation, he was wrong. The death of his closest brother Gunther happened in 1970. Following and during a dangerous ascent, an even more hazardous descent took place down the Himalayan peak of the Naked Mountain or Nanga Parbat, as it sloped down deep snow, avalanche, sheer ice walls and unforgiving scree into the foothills of the beautiful valley of Gilgit Pakistan below. This death of his brother was to follow him every day, a shadow of spectral density that served to drive him, but one which his enemies fed on like hungry ghosts. Fourteen years after Reinhold lost his brother on the descent down the mountain, Werner Herzog (the German filmmaker) found out Messner was returning to climb—not the Naked Mountain itself, as it had taken eight of his ten toes, but a less dangerous climb of the mountains nearby. Herzog asked Messner at the base camp, 4000ft up, the night before the ascent: ‘Do you suppose you two brothers were so close, your brother died in your place, and may have given you a different attitude towards death?’

Messner replied, ’I have a different attitude towards death in general because of climbing and perhaps because of my brother's death. Even though I still have the feeling he is alive, and not just in dreams, but say when I look at the mountains we climbed together. We were together in the hardest climb I have ever been on, we were in the tough situations and one was responsible for the other if we fell, and that welded us together so intensely that we can never be separated again. And whenever I look at that rock face today…I have the feeling he is still alive and I feel those hard, dangerous, so intense moments again, just as he feels them as if he were with me. I don't have that feeling he died in my place. I have the feeling that I myself died in that expedition.’

Although Messner was used to controversy in as much as anyone could be, the insults he received around the death of his brother were even harder to take, as they not only came from those whom he set out with on that fatal day but these same fellow climbers formed the small group that both he and his brother always looked for some support from. Reinhold and Gunther were brothers but something even deeper bound them. Their father Joseph was a World War I veteran, who returned to the small alpine village in the Villnoss Valley, shell-shocked, unable to come to terms with his war fatigue or to safely process his violent rages either against the dogs they kept, his nine children, or their long-suffering mother. One day Reinhold went looking for his younger brother Gunther and found him, after much searching, cowering in the dog kennel. Their father had beaten him so badly with the dog whip he was unable to walk. He helped him and tried to protect him from his father's later rages. Reinhold learnt to stand up to his father so by the age of 10 his beatings were not as severe. Together they shared this terrible secret about their father whom they also tried to love, but Gunther and Reinhold had also become wise children and bonded allies against the injustices of the world.

As they grew up, young Reinhold and Gunther impressed the older, more established climbers and were invited on what would turn out to be this most fatal climb in 1969/70.

Neither Gunther nor Reinhold knew that this climb was organised because of an obsession by the team leader regarding his half-brother Willy Merkl who had led a fatal expedition financed by Nazi Germany in 1934 and the particular Nazi fantasy around all things mountainous and epic. An attempt in 1932 by Merkl had failed, as he was hopelessly unprepared for the challenges of the Himalaya. This time, despite Nazi funding and to add to the delusion, Merkl had wanted the entire team, including two other climbers and six sherpas, to immediately arrive at the summit in a grand finale fitting of a Leni Riefenstahl film starring or directed by her. Riefenstahl happened to be a favourite of Hitler, as indeed were all ‘Bergfilme’ or mountain films produced under the rise of the Nazis. This time Merkl was one of many German climbers who wished to turn fantasy into fact. His mob-handed ascent proved fatal when all the climbers and the sherpas died. In 1938, another German expedition found his frozen body, along with a sherpa, in a snow cave. The 1932 and the 1938 teams were members of the German and Austrian Alpine Club, both nationalistic and rife with anti-Semitism and with a notorious ‘Aryan paragraph’ going back as far as 1899 in its club documents.