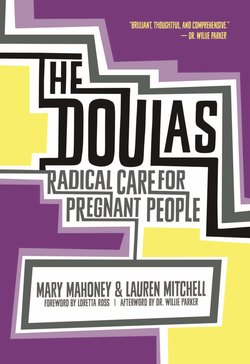

Читать книгу The Doulas - Mary Mahoney - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThank God for the Doulas!

Most people have never heard of doulas, but I’d venture that all pregnant people could use one. Having a person who unconditionally nurtures you during a major life experience is a privilege too few enjoy. Doulas provide this exquisite nonjudgmental support to others—often strangers—and touch peoples’ lives in profound ways.

The original doula was a female slave (from the Greek word “doulē”), and the term eventually evolved in the past forty or so years to designate women trained as birth attendants. In 2008, though, a trio of young activists launched the concept of “abortion doulas” into the zeitgeist. By imagining the doula role anew, they expanded the meaning of the word to include the full spectrum of possible pregnancy outcomes—births, adoptions, abortions, miscarriages, and deaths—as well as services to women, men, transgender, and gender nonconforming people.

These new doulas proudly bear witness to the lives of those they serve, transforming themselves in the process. With little experience but plenty of empathy, Lauren Mitchell and Mary Mahoney helped create a full-spectrum doula movement to expand the caregiving model into one that covers the entire range of life possibilities. As activists as well as service providers, they articulated a new dimension of the human rights movement for reproductive self-determination, based on passion, service, and advocacy.

An inspiring group of full-spectrum doulas tell their stories in this book. Some serve in hospitals. Others labor in abortion clinics or at adoption agencies. Others work in homes. Together, they represent a fresh generation of caregivers who weave diverse pregnancy experiences into a holistic service and advocacy model that challenges stigmatized, artificial divisions among pregnancy outcomes. The same people who give birth sometimes have abortions or miscarriages. Some births culminate in an adoption. Every pregnancy is different, and each has its own finale.

That simple truth is why this book is precious. The stories of these full-spectrum doulas and their collective knowledge help end the painful social stereotypes that cause pregnant people to be categorized as good or bad based on a pregnancy’s outcome. Through the eyes of doulas, we witness the range of pregnancy experiences affected by imbalances of power, privilege, and knowledge, whether pregnant for four weeks or nine months. These doulas call it “story-based care” because they hear many stories of people for whom some choices are straightforward, while others offer extreme complexity, requiring the deftly engaged services of doulas who can handle both emotional and technical difficulties.

We also learn how important it is for doulas to take care of themselves in order to be brave for people whose experiences may be shrouded in stigma and secrecy. Doulas give so much emotional, physical, and spiritual support to others that they may fail to save some love for themselves. They join the movement to serve, not to be served. Because they see the macro-level systems that shape the experiences of their clients, they can let their desire to help fight injustices disguise their need to replenish themselves. But an empty vessel can’t fill others. When they come up against burnout, cynicism, and rage, this new cadre of reproductive justice activists must help each other recalibrate, regroup, and reaffirm their commitment to themselves and others.

Unlike most caregiving services, abortion doulas are exposed to the physical and emotional dangers also faced by clinic doctors, nurses, receptionists, and escorts, some of whom have been killed or assaulted by violent vigilantes. After all, clinic escort James Barrett was killed in Pensacola, Florida, in 1994 along with the doctor, John Britton. In 2015 two civilians killed at a Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood—Jennifer Markovsky and Ke’Arre M. Stewart—were at the clinic supporting friends. Worrying about domestic terrorism while providing a medical service should not be a part of a doula’s repertoire, but these activists generously help others navigate these perils, even as they face the threats themselves.

Like many, I experienced pregnancy as a totally life-altering event for which I was not prepared. I felt a confused mixture of wonder and terror during my first pregnancy as a teenager in the 1960s, not quite believing it was happening to me. I knew little about sex and less about pregnancy. I marveled at the changes in my body and its potential for motherhood. I felt like an adult emancipating from childhood. At the same time, I was in an exhausting state of denial. I remember hoping that the pregnancy would be gone when I woke up and my body would revert back to its prepregnancy state. Now, looking back as a grandmother, I know fear filled me. The primal fight or flight reflexes were dominant. And, because abortion was not legal at the time, my family knew of only two options for me: to keep the baby or choose adoption.

Full-spectrum doulas did not exist then, but I can tell you now that I desperately needed one. My mother was traumatized by the incest that led to my pregnancy and she scarcely knew how to advise me, much less offer any support or care. My father was angry that this had happened to his daughter, and felt powerless to visit his hurt and rage on our miscreant relative. While I was assured of their love, I didn’t know anything about the process of pregnancy and birthing, or how to evaluate my few reproductive options.

My parents placed me in a Salvation Army home for unwed mothers, a barbed-wire compound established so that teen pregnancies could be hidden from society. The babies that issued forth from these traumatized girls mostly disappeared into adoption agencies. I was the only black girl there, but I didn’t argue with my parents’ decision. It was not an unusual refuge for pregnant teenagers of the day, and it seemed like the best choice we could make at the time. I was fifteen.

The delivery was traumatic, not so much physically, but because of my fear, the intensity of birth, and my lack of knowledge about what was happening to my body. The home did not provide any pregnancy education or preparation. One minute we were doing chores or saying prayers—the next minute we were in labor and whisked off to the hospital. There was no phone available to the girls; it wasn’t certain that even our parents were called. All I know is I had a very lonely labor—my parents did not make it to the hospital before the baby arrived the next day.

What a difference a doula would have made. Someone to tell me about my body’s processes, what delivery would be like. Someone to squeeze my hand or make eye contact with during contractions—someone to help the doctors and nurses when the unexpected occurred. Scared does not begin to describe my feral panic. When I hear of doulas working with women to establish birthing plans and ensure that medical staff respects them, I marvel at how different pregnancies can be because of their visionary compassion.

As hard as giving birth under those lonely, terrified circumstances was, the harder moments came after birth, when I needed an advocate. I decided to place my son for adoption because I did not want this tortuous path to motherhood. I was in tenth grade, had college in my future, and did not want to parent my rapist’s child. But everything changed when the nurses placed my son on my chest. I couldn’t go through with the adoption, but I wasn’t ready to parent either. I hadn’t even selected a name for the child I was now going to keep.

As soon as I articulated that I wanted to raise my son, I was assailed by the hospital, the Salvation Army home, and my parents—all of whom wanted me to stick to the plan and place my son for adoption. I had no one to listen to me. My parents eventually supported my decision. They co-parented with me through high school and college, and I recognize what a privilege it was to enjoy such strong family support.

A few years later, I made a different parenting decision under different circumstances. I had an abortion as a first-year college student. Over the years, I have witnessed women making reproductive choices under diverse life circumstances. I have escorted a few friends to abortion clinics, and I’ve given money to other friends who couldn’t afford their procedures. To me, then, this book is a celebration of the fact that we’re fortunate to live in a new era in which advocates and caregivers can center the needs of the pregnant individual regardless of the decision that person ultimately makes.

I can attest to how desperately this movement is needed. The last person I escorted to a clinic was a twelve-year-old girl still sucking her thumb who was, in all probability, the victim of childhood sexual abuse. She urgently needed a doula because her mother—likely emotionally overwhelmed herself—appeared deaf to her daughter’s obvious signs of distress. A doula could have helped the mother and the daughter both—maybe even assisted them in selecting a birth control option. The mother had refused to even consider the possible future need.

Doulas provide services at the intersections of our most essential human rights: the right to give birth, the right to not give birth, and the right to safely parent children—the three cornerstones of reproductive justice. Crafted by African American women in 1994 and powerfully popularized by radical women of color, reproductive justice organizes the collective knowledge of women of color based on our pregnancy and parenting experiences. It turns that knowledge into new analyses that recognize how our own value systems based on human rights connect us to each other, and confronts the concussive impact of multiple oppressions on our reproductive lives. Racism can distort a birthing or adoption experience. Transphobia can lead to the denial of vital healthcare. Prejudice against immigrants can divide families through deportation. Misogyny can reduce pregnant women to walking wombs without rights. These are all reproductive justice issues, and doulas are the birth justice wing of our movement.

Doulas understand the unique nature of each person’s situation. At the same time, they comprehend the systemic factors that affect these experiences, such as race, age, English proficiency, citizenship, gender identity, class, and the host of integrative—not additive—forces that contour pregnancy experiences. They don’t shy away from naming oppressions—white supremacy, colonialism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia—yet they are not there to preach, but to serve. Their actions to support each and every pregnant person speak louder than any polemic on reproductive oppression or the medical industrial complex.

In a sense, these new doulas echo the full-service midwives of previous centuries. When physician-based medical care was unavailable to many people, they relied on midwives who handled births and deaths. These midwives were trusted, respected, and valued for the critical role they played in people’s lives from beginning to end. Through similar compassion and dedication, contemporary doulas are creating a new tradition and demonstrating profound expressions of feminism in action. If activism is the art of making your life matter, the doulas are activists extraordinaire.

—LORETTA ROSS

Atlanta, Georgia

January 2016