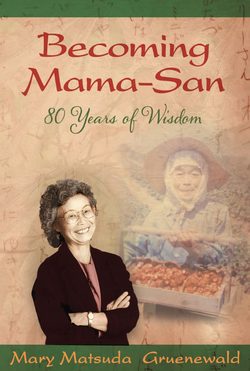

Читать книгу Becoming Mama-San - Mary Matsuda Gruenewald - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE The Privilege of a Simple Life

ОглавлениеMy family lived the American dream in the early years of my life. Not the modern version of glittering excess that is often portrayed in the media, but the original dream that the founders of this country would have recognized. My family had a sense of considerable freedom living in a democratic society, with far more opportunity than we would have had anywhere else. We were grateful to work hard and better our lives. Ours is a story of an immigrant family that worked steadfastly, endured hardship, and made any sacrifice necessary to fully participate in everything this country has to offer. My parents felt fortunate to raise their children in the United States. Over the years, we would not be deterred, even when our country turned against us.

I was born in Seattle, Washington in 1925. Some people might think of my childhood as impoverished because by today’s standards, I did not have a financially privileged life. Instead, what I had was a rich environment full of natural beauty, the opportunity to explore and learn through direct experience, and a chance to develop self-reliance. My parents’ gratitude for simple things was key to their worldview—one that eventually became my worldview. They passed on wisdom that, to this day, has given me the strength to transcend life’s ordeals.

My father, Heisuke Matsuda, was born in 1877. Papa-san was fifteen years older than my mother, Mitsuno. In the Japanese-American community, they were known as Isseis, first generation immigrants, born in Japan. My brother, Yoneichi, was two years older than I, and we were called Niseis, born in the United States, and therefore, we were American citizens.

My earliest memories were of a modest life at our first home on Vashon Island, about a twenty-minute ferry ride from Seattle. My parents rented an old drafty house in the country where the curtains waved in the breeze even when the house was completely closed up. The house sat in a wooded area on a flat plateau. Below us was Puget Sound to the southeast, but all we could see were trees. Our two neighbors lived about a mile away, and I had no regular playmates other than Yoneichi.

We didn’t have electricity, which for rural areas was still something of a luxury in the 1920s. We pumped cold water by hand from a well located outside the back door, and heated it over a wood stove, which also heated the house. We took baths in a primitive galvanized tub in the middle of the kitchen floor. An outhouse situated fifty feet out the back door was our bathroom, no matter the season.

Our lives revolved around our immediate neighborhood, a much smaller area than most people operate in now. Our family farm and home were located on the same piece of land. We bought groceries from a store down the road, about one mile away. We raised chickens and had a goat that provided milk. We grew much of what we needed to eat. We walked everywhere since we had no car. Cars were not readily available in my childhood, but we didn’t need them either. We had no radio, telephone, TV, or refrigerator, not even an icebox. Despite our lack of conveniences, we were content.

You could say we had a richness of place and family, but not things! Our only toys were a tricycle for Yoneichi and a kiddy car for me. Nature and miles of wide-open countryside surrounded our home. In those early years, nature was our main source of wealth, providing a means to grow our food and make a livelihood. It also fed our souls with its beauty, and provided me with many vivid life lessons.

One of my earliest memories was when I was about four years old. One hot, muggy afternoon, I was sleeping on my bed while my parents worked outside. Thunder woke me up and I rushed to the back door just in time to see lightning strike the top of a tall Douglas fir nearby. A raging ball of fire raced down the entire side of the tree, peeling off the bark before it plunged into the ground with a deafening BOOM that shook the house. Rain followed in torrents, soaking my parents as they scurried from the fields back to the house. Trembling, I stood frozen on the back step.

“Mary-san!” my mother shouted, breathless, as she swooped me up in her arms and rushed inside. We were both shaking.

What I remember some 80 years later is that in my moment of sheer terror, my mother and father were there to comfort and protect me. A feeling of safety imprinted on every cell in my body. This would be the first of many times I remember my parents being there for me—a knowing I would hold onto for a lifetime.

Nature’s power, whether it was giving or taking, influenced me profoundly in my early years. One time, my parents were taking the long loganberry canes and winding them between two rows of wire that had been strung for this purpose. They were worried because a wildfire was burning on the island. While they worked, I swung on the wire and prayed out loud to God: “Kami sama, ame oh fu’te kudasai. Faya oh keyasa nai kara.” “God, please make it rain because we have to put out the fire!”

To my surprise and delight, it rained that night. Years later, Mama-san talked about this incident, reminding me, “It rained hard enough that by morning the fire was out! Amazing what the earnest prayers of a little child can do!”

On warm summer days, we walked about a mile down the hill to the shores of Puget Sound. The beach was covered with a variety of shells, colored rocks, and driftwood, which I collected and arranged in designs on the beach, only to have the high tide wash them all away. I liked playing with different kinds of crabs and watching them run sideways away from me. Sometimes, we would bring a bucket and dig for butter clams that Mama-san would later cook for dinner.

Once, I saw my parents walk down to the beach in their bathing suits and go for a swim. I could hardly believe my eyes. I didn’t know they knew how to swim or even that they had swimsuits. Mama-san had tucked her black hair into a swimming cap and she looked trim and tanned. Papa-san had a farmer’s tan with his face and neck much darker than the rest of his body. He was a small man, but solid and muscular from years of hard work. Laughing and calling to each other, they took big strokes away from me and lazily swam in the calm waters. It tickled me to see my parents playful and relaxed. Usually, they were too busy working in the berry fields, planning for the day they would own their own farm. This would be my only memory of seeing my parents swim.

My first home near the shores of Puget Sound was a Garden of Eden. Towering, thick, old growth trees bordered two sides of our home, creating a cathedral that opened to the sky. There were all kinds of places to explore at the beach and in the woods, ever-changing with the seasons. The world was my playground, and the birds, fish, snakes, and even angleworms were my playmates. In summer, I’d eat fresh fruit right off of the vine or low hanging branches—wild salmonberries, Italian plums, and crisp apples.

Despite the usual bumps and bruises of childhood, I felt completely safe in nature, and comforted. Nature would later become my refuge during those times when the world was harsh and unjust.

In early 1929, my father fulfilled a lifelong ambition by cashing in his life savings and buying ten acres of farmland near the center of Vashon Island. To this day, I am amazed by the wise and fortuitous timing of his decision, coming as it did shortly before the stock market crash of October 1929. He planned, worked, and saved for twenty-seven years before deciding the time was right.

Papa-san hired someone to build a four-bedroom house, and for two years during the start of the Great Depression he provided work and income for the island’s hardware store, lumberyard, and tradesmen. In 1931, we moved into our new house, which had all of the modern conveniences of the time, including electricity, hot and cold running water, an indoor toilet that flushed, and a utility room. All of our friends and neighbors came to our first open house. Mama-san prepared sushi, teriyaki chicken, and teriyaki salmon. The new, extra long kitchen counter, built unusually low to accommodate Mama-san’s five-foot stature, was brimming with even more food brought by our guests. It was an all-American potluck dinner with a Japanese twist!

Our new home wasn’t extravagant, but compared to the one we had lived in, it was the height of luxury. Yoneichi and I even had our own separate bedrooms. The new house was much warmer in winter and cooler in summer. Our house was among the nicest of those owned by the Japanese families on the island. I was proud of this fact, but Mama-san had to remind me repeatedly not to brag about it.

The oil stove in the living room provided heat for the upstairs bedrooms through a vent in the ceiling. Mama-san cooked in the kitchen with a wood-burning stove. When it was time for chopping wood, all four of us pitched in. Papa-san split the huge chunks of wood in half or quarters. Yoneichi and Mama-san cut those pieces and split them to fit the kitchen stove. I had a small hatchet for making kindling from the larger pieces of wood. We all worked together and even as a small child I felt as though I was an important part of the effort.

The four of us, along with our horse Dolly, labored year-round, farming a variety of berries in those early years. Later, we specialized in strawberries, as my father found them to be the best crop. Every summer, he recruited workers of all ages from Seattle and Vashon to harvest the fruit, which was taken by truck to be processed into jam and jelly. As one of the island’s chief employers of school-age children, he influenced many families in positive ways. Child labor was common back in the Depression era, and some of the families needed the income from their children’s labor to buy essentials.

There was a pond in the next field over where Yoneichi and I played after the day’s work was done. When we first moved into our new house, we didn’t know the pond was there because it was hidden by tall grass and brush. It was a thrill when we first discovered it. Nearby, we found a crude raft and a long pole, so naturally we explored the pond’s environs. I was always a little afraid of the unknown dangers I conjured up in my mind, lurking just below the pond’s surface, but Yoneichi would often float about the pond by himself.

The pond was full of pollywogs in the spring, and later in the year we could hear the chorus of croaking frogs every evening. We would find clumps of eggs and bring them home in a jar and wait for the pollywogs to hatch. It was fascinating to watch them develop their legs and eventually turn into frogs. We never kept them until they matured, but instead returned them to the pond and let them go free. The pond was a treasure, a hidden preserve full of mystery and adventure, just for Yoneichi and me.

Spirituality was important to my parents, so Yoneichi and I joined the Vashon Methodist Church, which happened to be the first church we encountered on our walk into town. Papa-san and Mama-san didn’t attend because their English wasn’t good enough to follow the services, but Yoneichi and I quickly became comfortable there. When Mama-san first came to America, she moved on from the Shintoism of her youth and embraced Catholicism in her adopted country. But when Yoneichi and I began telling our parents about what we were learning at the Methodist church, Mama-san got curious, and soon, she and Papa-san joined the Japanese Methodist church in Seattle.

Occasionally, when the minister was available, my parents hosted services in our home for Japanese-speaking Isseis on the island. The services were Methodist, but the people who attended were of a variety of faiths, including Shinto and Buddhist. Another family on the island held occasional Buddhist services in their home, and we also attended those whenever we were invited. At the Methodist services, we sang hymns that I had learned in church. The Isseis sang in Japanese while I sang the same hymn in English. At the Buddhist services, I listened and had prayerful thoughts in English while the priest chanted, rang a gong, and lit incense in front of the altar. I couldn’t understand what he was saying, but the atmosphere made it easy to pray to God.

I was comfortable in all of these situations. It felt perfectly natural for me to grow up in this mixed spiritual environment. I knew only that God is God of all of us, and the language, rituals, and even teachings didn’t change that.

Cultural education was also important to my parents because they wanted us to retain a sense of our Japanese heritage. When I was in the eighth grade, they sent Yoneichi and me to kendo classes, where I was the only girl. Kendo is a martial art that requires full body armor and a padded helmet, and teaches discipline of mind, body, and spirit. My parents registered me for the class not only for the exercise and discipline but also for my posture. Whenever I walked, my head leaned out in front of the rest of my body. Kendo required me to stretch my arms back behind my head, forcing my posture to be more upright.

When we had learned enough of the basic strokes, we were told to put on all the armor for our first taste of combat. My heart was already beating briskly from the warm-up, but my whole body broke out in a sweat as my muscles tensed in preparation to fight. I was paired up with a boy a year older than me. At the word to begin, “Hajime!” he took a swift swing at the left side of my head. Stars flew, I heard ringing in my left ear, and I staggered to maintain my balance. I was stunned, not expecting him to act so quickly.

The teacher standing beside us shouted, “Raise your shinai! Defend yourself!” The boy hesitated. In that moment, I angrily and swiftly swung my shinai and hit him on the padding on the left side of his neck. I said to myself, There, how do you like that?

I felt satisfied that I had evened the match. That was the end of our encounter. After that, the teacher paired up other students to give each one a chance to engage in combat. Kendo gave me many things in life, including a sense of comfort and confidence during times of conflict. Thanks to kendo, I have had good posture ever since. And in the years and decades that followed, it allowed me to negotiate many battles with deftness and integrity.

Because we lived in such a small community, my grade school went from first through the eighth grade. I looked forward to the big step to high school, and though I was anxious, it was easier knowing that Yoneichi was already there.

About thirty-five of us attended the orientation for the incoming freshman class, where each girl was assigned a “big sister.” Mine was a popular white girl named Bobbie, who was a senior. She put me at ease immediately, and introduced me to a number of girls and female teachers. I felt special having such an outstanding student as my “big sister.” Later, I realized this honor may have been influenced partly by Yoneichi’s high standing in the school. Maybe they expected me to follow in his footsteps.

In those days, I did not detect any racism on our island. Vashon High School was a melting pot in which Japanese-American students held leadership roles. We were well represented in the student government, the Honor Society, and sports. Yoneichi participated in all of these activities as the secretary of the student body, and as a short but fast player on the varsity football team.

High school presented the usual challenges for me, along with some that most of my Caucasian peers wouldn’t expect. For the first time, students my age gradually started pairing off, but none of us Japanese-American students would dream of doing so. It just wasn’t culturally acceptable to date, certainly at that age. It was an unspoken assumption in the Japanese culture that we would have arranged marriages, which made dating unthinkable. But for me and my Japanese peers, watching our classmates date opened us up to a whole new set of ideas. I began to wonder if an arranged marriage was best for me, and whether I could be happy in such a relationship.

At school, I found myself interested in a handsome, athletic white boy, and we enjoyed chitchatting with each other. I knew my parents would not approve, so mentally I kept him at arm’s length. Still, I couldn’t help but think about him, and I wondered what he thought about me.

One day, while we were preparing dinner together, I asked Mama-san, “Am I beautiful?”

She looked up at me briefly, surprised, and then turned back to the carrots she was chopping. “No, you’re not,” she replied, matter-of-factly. “But be grateful for the face you have. If you were too pretty, boys might pursue you for your looks alone. On the other hand, if you were ugly, they might avoid you because of that.” Mama-san smiled at me and continued, “Be grateful for the face God gave you.” Then she swept the carrots off the cutting board into a saucepan.

I looked down at the floor to keep from showing Mama-san that I was very disappointed, but deep down I knew she was right. If she had said that I was beautiful, I might have thought she was saying that to keep from hurting my feelings. I thought about what it would be like to be beautiful and glamorous, like Greta Garbo, Carole Lombard, or some of my other favorite movie stars. Wistfully, I imagined crowds cheering for me and asking for my autograph, knowing that it would never happen. As it was, I decided I had an ordinary looking face and a healthy, maturing body. I knew Mama-san loved me just the way I was, and that was enough. I could always count on her to be completely truthful with me.

My mother’s blunt honesty was just one of many ways in which my parents demonstrated an unusually deep level of respect for me. Looking back, I think they were both quite extraordinary. While my mother and father were clearly products of their culture, they were also quite different from most of their peers in important ways.

My father treated his wife as an equal at a time when the Japanese tradition was that the husband made all of the decisions. His charm extended to the way he was quietly considerate of others. One of my adult friends recalled that Papa-san was the only one at community gatherings who brought special treats for all of the children, such as soda pop or candy. As a boss, when dozens of workers came to our farm to help with our harvest, he would give each of them candy at nine o’clock every morning. And to celebrate the end of the harvest, he bought ice cream for all of the workers and any of their family members who showed up—even during the height of the Depression.

Many Japanese fathers gave special attention to their oldest sons, and Papa-san clearly had expectations for Yoneichi that he didn’t have for me. But Papa-san made me feel special, as well. When he and I ran errands together in Seattle or Tacoma, he always made it fun. When we went to Seattle to see the optometrist, we always went to Maneki’s restaurant and had the same thing for lunch every time: miso soup, rice, and buta dofu (pork with tofu). After lunch, we would tour different stores, or visit a family friend, or have an ice cream soda.

My mother was the youngest of ten children. Her father died when she was only two, and her mother died when she was six. She ended up being raised by her adoring older siblings, who nurtured her and provided her with an education far beyond what most Japanese girls in that era received. Her outlook on life was always upbeat and positive, even in the most difficult of times.

As a family, we talked with one another more than most, and in a different manner. My parents were genuinely interested in my brother’s and my daily lives, but I never felt like they were prying. I felt comfortable talking about school, my friends, or whatever else was on my mind. Sometimes, Mama-san or Papa-san told us of their early lives, including Papa-san’s harrowing experiences, as a young man, of extreme prejudice. No topic was off limits.

Both of my parents had a sense of adventure and a relative lack of need for control. From a young age, I felt respected and loved by my parents. It did not matter that my wants and desires might change from one moment to the next, or that they might seem unimportant to an adult; my thoughts and opinions were still honored by them. Their guidance was gentle, and mostly by example, rarely verbal. Arguments were almost unheard of in my family. Punishments were meted out with care, but hardly seemed necessary except on the rarest of occasions.

Later, it was this degree of respect from my parents that ironically would allow me to deviate from the path that a Japanese daughter was expected to follow. My decision to marry a hakujin (white man) in 1951 created the only serious conflict between my parents and me. At that time, interracial marriages were rare in the United States. A strong but unspoken sense of cultural pride within the Japanese-American community implied that marrying outside of our community was “beneath” us.

As open and as generally accepting as my parents were, nothing prepared them for the shock that I delivered on the day I announced my engagement. It was a scandal that brought shame on my family. And yet, once their dismay wore off, my parents’ values and respect for me would win out, overcoming their initial expectations that came from culture and precedent.

In accepting my husband into the family, my parents came to a new appreciation of the fundamental truth that all people are created equal, an ideal central to Americans. It is a simple concept, but one that is difficult to live up to in practice, especially during times of conflict, or when social norms interfere with our ability to understand and accept other people.

During World War II, my family suffered greatly at the hands of Americans who did not understand this fundamental truth. And because of the trauma I endured then, it would take a lifetime of affirming events for me to fully return to a belief in my own worthiness. I could not have made this journey, from the depths of depression back to acceptance, without the privileges I was afforded as a child—a simple life, close to nature; an emphasis on hard work and self-reliance; and the unconditional love and respect of my parents.