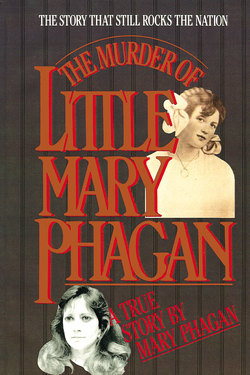

Читать книгу Murder of Little Mary Phagan - Mary Phagan - Страница 10

ОглавлениеAnd, as my father said, my legacy is a proud one. And if, as he’d exhorted me, I was going to let the world know that I was Mary Phagan, greatniece of little Mary Phagan, I wanted to find out everything I could about my namesake—and our family.

By age fifteen, I was certain of one thing: my life would be shaped by my relationship to little Mary Phagan. And I was excited about discovering my legacy. I got the desire to read everything I could on the case.

My mother and I went to Atlanta’s Archives to discover more. My mother, like me, was unaware of the family history, especially concerning little Mary, and she, too, wanted to learn more. When we signed in at the Archives, the librarian looked stunned. Again, I was asked that question: “Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan?”

I told her I was and she directed us to a smaller room which contained photographs of the history of Georgia. One of these photographs was the frightening picture of Leo Frank hanging. For me, this was the final catalyst.

Once I had seen that picture, I attempted to read everything—books, newspaper articles, even the Brief of Evidence. The information was difficult and, being only a teenager, I found it hard to understand and digest. It raised more questions for me. Again I turned to my father for answers.

This time my questions were more direct. I wanted to know everything about the family, the trial of Leo Frank, and the lynching.

And this time his answers were deeper and more complete.

“My great-great-grandparents, William Jackson Phagan and Angelina O’Shields Phagan, made their home in Acworth, Georgia. Their land off Mars Mill Road was also home to their children: William Joshua, Haney McMellon, Charles Joseph, Reuben Egbert, John Marshall, George Nelson, Lizzie Mary Etta, John Harvell, Mattie Louise, Billie Arthur, and Dora Ruth. Two other children had died during childbirth.

“These children grew up to be very close to one another. Their father, W.J., believed that that was what the family unit was meant to be: by depending on each other and furthering their education, he was sure, the Phagans would get far ahead in the world.

“The eldest son, William Joshua, loved the land and farmed with his father. On December 27, 1891, he married Fannie Benton. The Reverend J.D. Fuller presided over the Holy Bans of Matrimony for them in Cobb County, Georgia. W.J. gave them a portion of the land and a home of their own, and Fannie and William Joshua farmed the land together. They, too, became successful farmers.

“Around 1895, W.J. moved the family to Florence, Alabama. William Joshua and Fannie, now with two young children, Benjamin Franklin and Ollie Mae, moved with them.

“The family’s new home, purchased from General Coffee, had been a hospital during the War Between the States. The house needed extensive renovation, but posed no financial burden on the family. W.J., Angelina, and their children lived in the main house; the young couple’s new home was not far away.

“The years in Alabama were good for them, especially for William Joshua and Fannie. They had two more children, Charles Bryan and William Joshua, Jr. They continued to farm the land.

“In February of 1899, William Joshua Phagan died of measles. Fannie, who was then six months pregnant, was left with their four young children. She was devastated but kept her courage up: she knew the child she was carrying could be in danger. On June 1, Mary Anne Phagan was born to Fannie in Florence, Alabama.

“Fannie remained in Alabama long enough for her and her baby daughter to gain their strength. Then she moved her family back home to Georgia, where she planned to live with her widowed mother, Mrs. Nannie Benton, and her brother, Rell Benton.”

“Why did she move away from her husband’s family, when they’d been so good to her?” I asked.

“Oh,” my father smiled, “I don’t believe she was so much moving away from her husband’s kin as she was moving back to her own kin. Anyway, hang on,” he grinned at me. “Thing is, it turned out that the families weren’t separated in the end, after all.”

He shifted in his chair. “Well, anyway, Fannie probably also figured there’d be more opportunities in a densely populated—well, relatively densely populated—area. Notice I didn’t say city. ‘Cause Marietta was far from that, then. What it was was a country town with a population of about three thousand five hundred. And Southern society was changing rapidly: the younger generation did not know the high feelings of the War Between the States and Reconstruction. The War and its aftermath no longer dominated society and politics.

“The square in Marietta was the center of every aspect of life. It was an arena of sorts for social, political, and agricultural activities and the center of transportation and communication for both residents and visitors.

“Then—see what I meant?—W.J. Phagan moved his family back to Georgia as well. The death of his eldest son so bereaved him that the family could no longer remain in Alabama. He purchased a log home and land on Powder Springs Road in Marietta. WJ. also provided Fannie with a home for her and her five children to live in. He saw to it that they had no hardships.

“About 1907 the last of the Phagan family left Alabama and returned to Georgia. Reuben Egbert and his family moved back to their native state and remained there for the rest of their lives. WJ. kept an eye on all his children and his grandchildren, and by 1910 had all of them nearby him, as well as financially secure, in Marietta.

“Fannie Phagan and her children appreciated what W.J. was doing for them, but they also felt the desire to support their family themselves. So sometime after 1910 Fannie Phagan and four of her five children moved to East Point—Atlanta—Georgia, where she started a boarding house, and the children found jobs in the mill. Charlie Joseph, the middle child, decided he wanted to continue farming and moved in with his Uncle Reuben on Powder Springs Road in Marietta. Around that time Mary found work at the National Pencil Company in Atlanta.

“The Phagan family remained close with relatives in Marietta. Every so often one of Mary’s aunts—Lizzie, Ruth, or Mattie—would ride the trolley from Marietta Square to East Point to pick up Mary and bring her to W.J.’s house. The family always loved having Mary there, especially her female cousins, Willie and Lily. When the cousins got together—usually in the summer, when school was out—they played games—hide and seek, hopscotch, dolls and house. But Mary’s favorite game was house. The girls would clear a clean spot in the shade, place rocks in it for chairs, and then decorate the ‘inside’ of the ‘house’ using limbs from trees or other big branches already on the ground. Their ‘house’ would show the distinct rooms—kitchen, bedroom, bathroom, etc. But usually in the bedroom they would have a babydoll. Dolis were different back then. Most of them had stuffed bodies but their heads were called ‘China.’ When they would push the babydoll in its carriage, one foot would fly up! The girls could always be heard giggling and laughing together. They cherished those times together. And especially since visits were getting fewer.

“Usually, Aunt Lizzie would make the girls their clothes. How excited they got! They loved new things, just like everyone else. Sometimes Aunt Lizzie would take them to Marietta Square for a shopping trip. They’d get on the trolley where it began—Atlanta Street. Remember, the Square was the center of activity and the girls delighted in seeing things ‘downtown.’ Sometimes they would just ride the trolley car.

“Even though Mary stayed busy at WJ.’s, she always found time to drop Grandmother Fannie a note.”

Here my father stopped and took a postcard Mary had written to her mother: it was postmarked Marietta, Georgia, June 16, 1911, 6:00 p.m.:

Hello Mama,

How are you?

I got here all O.K.

I would have wrote sooner

but I hadn’t thought about it.

Willie is up here.

Aunt Lizzie has got my gingham

dress made. I am

going to have my picture made soon.

Your

baby,

Mary

We were both deeply touched by the way Mary had signed the card.

“On February 25, 1912, Fannie married J.W. Coleman, a cabinet maker. He was a good man and accepted her children as his own. And they all liked him and accepted him as their stepfather.

“They moved to J.W.’s house at 146 Lindsey Street in Atlanta near Bellwood, a white working-class neighborhood.

“Well, Coleman didn’t have much money, but he wasn’t considered poor by any means. After marrying Fannie, he requested that her youngest child, Mary, quit work at the Pencil Company and continue her education. But Mary liked her work at the factory and didn’t really want to quit.

“Eventually, Fannie’s eldest, Benjamin Franklin, who worked as a delivery boy for a general merchandise store, joined the Navy. Ollie Mae became a saleslady for Rich’s Department Store. William Joshua, Jr., continued to work in the mills. They didn’t seem to mind working at all, because they were earning money.”

“Why did anyone mind?” I asked.

“Oh, mill life was anything but easy then.” He looked out the window. “The conditions were awful; mills were filthy and lint was everywhere. Child labor laws weren’t enacted ‘til years later. Small children were hired as sweepers and were whistled at to keep moving. My mother, Mary Richards Phagan, was eleven years old when she became a spinner at the mills. She was so small, she was one of the first to be run away from the ‘officials’—the labor representatives—when they came by. It was hotter than the hinges of Hades, and cotton was always flying through the air. In fact, the flying lint eventually became a term for those who worked in the mills: lint-heads.”

“Okay, Daddy,” I interrupted. “But life in Atlanta must have been more exciting than life in Marietta—or Alabama.”

“Cobb County itself had a county population of twenty-five thousand. There were no paved roads in Marietta and Cobb County, including the square in Marietta. People used wagons and carriages; virtually no one owned an automobile then. If they chose to travel the twenty-five miles to Atlanta, they used the N.C. & St. L. Railroad or the electric streetcar line.

“Telephone service had come in some twenty-five years earlier—about 1890, or so. Water and electricity had only been available for five years.

“Cobb was considered an agricultural county and had practically no industries. In late autumn, the square in Marietta was filled with cotton bales. Throughout the summer it was filled with vegetables.

“Justice, law, and order were other areas that were vastly different then. After the War Between the States, the antagonism between those upholding the federal judicial system and those who wanted more local control of the courts led to night riders and lynchings. Men settled their differences immediately. It became a way of life.

“Atlanta in 1913 still hadn’t reached a half million in population—but it wanted to. It was a mule center and railroad town. But it had grown significantly since 1865.

“Oh, there was light industry, including the National Pencil Company at 37-39 Forsyth Street. Mills were the most numerous, and a few breweries.

“Life in 1913 was casual and slow. Folks got most of their news from local newspapers, which printed ’extra’ editions for late-breaking stories.

“Sanitary conditions were terrible. The facilities were few and far between and were located outside. Sanitation workers were called ‘honey dippers.’ Typhoid fever was all over the place.

“Boys wore knee pants until they completed grammar school. Women wore high laced high-heeled shoes and bloomers made of the same material as their dresses.

“There were no frozen foods. People had streak of lean and perhaps some beef for stew. Hogs were plentiful. Biscuits and milk gravy were staples. They had apples and oranges occasionally, but raisins had seeds in them.

“Photography was all over—not just in the newspaper. Tintype, most usually.

“For recreation, most entertained themselves. There was a form of baseball, ‘peg,’ that they played in quiet streets or in vacant lots. Movie theaters ran silent films on weekends, especially around the mill neighborhoods. The Grand Theater, the Bijou, and the Lakewood Amusement Park helped people forget their daily drudgery.

“The South hadn’t really recovered from the ravages of the War Between the States and Georgia was no exception. The economy was shifting from the land to industry. Families were resettling from small towns and farms into the urban areas. Wives and children were often forced to work in factories to help the family survive.

“Mary Phagan was a beautiful little girl with a fair complexion, blue eyes, and dimples. Her hair was long and reddish brown and fell softly about her shoulders. Since she was well developed, she could have passed for eighteen. Her family all called her Mary rather than her full name of Mary Anne.

“Mary was Grandmother Fannie’s youngest child. Your grandfather says that she had a bubbly personality and was the life of their home. Mary was jovial, happy, and thoughtful toward others. When she was with her family, she’d show her affection for them by sitting in their laps and hugging them.

“The last Phagan family gathering was a ‘welcome home’ for Uncle Charlie. There the family had begun to notice how beautiful Mary was. Lily, her cousin, who is still living, tells me that she envied Mary a particular dress she had on. It was called a ‘Mary Jane dress”—long, with a gathered skirt and fitted waist. Lily and her sister Willie were ‘skinny,’ and Mary’s dress looked better because she was ‘heavier’ than them. They both wanted their dresses to look like Mary’s did on them.

“Early in April, Mary was rehearsing for a play she was in at the First Christian Church. The play was ‘Sleeping Beauty,’ and of course Mary played the role of Sleeping Beauty. Your grandfather tells me that he would take Mary to the church and watch her rehearse. The scene where Sleeping Beauty is awakened by a kiss always made him and Mary giggle. She would watch her brother with her eyes half-closed, and then begin to giggle when he cracked a smile. It seemed that that scene took an eternity to rehearse.”

I could picture Mary on the stage playing the little Sleeping Beauty. “April twenty-sixth was Confederate Memorial Day, a Saturday, and a holiday complete with a parade and picnic. Mary planned to go up to the National Pencil Company to pick up her pay and then watch the parade. She told Grandmother Fannie she’d be home later that afternoon. One of the last things she did was to iron a white dress for Bible School on Sunday. She was a member of the Adrial Class of the First Christian Bible School, and she wanted to look her best so she might win the contest given by the school.

“She was excited about the holiday, though, and wore her special lavender dress, lace-trimmed, which her Aunt Lizzie had made for her, they tell me. Her undergarments included a corset with hose supporters, corset cover, knit underwear, an undershirt, drawers, a pair of silk garters, and a pair of hose. She wore a pair of low-heeled shoes and carried a silver mesh bag made of German silver, a handkerchief, and a new parasol.

“At 11:30 a.m. she ate some cabbage and bread for lunch. She left home at a quarter to twelve to go to the pencil factory. She was to pick up her pay of $1.20, a day’s work.” My father sighed and looked out the window.

“When Mary had not returned home at dusk, your great-grandmother began to worry. It was late, and she had no idea where Mary could be. Her husband went downtown to search for Mary. He thought perhaps she had used her pay to see the show at the Bijou Theater and waited there for the show to empty, but found no sign of her.

“He returned home and suggested to Fannie that Mary must have gone to Marietta to visit her grandfather, WJ. Since they had no telephone, they couldn’t communicate with the family to verify that Mary was with them. Fannie sort of accepted this explanation, since she knew how Mary loved her grandfather. It did seem plausible that she could be with the family in Marietta. But Fannie, being a mother, spent a restless night.”

My father paused, stared into the middle distance. I could see my grandfather pointing to Mary’s photograph, then to me, then sobbing almost uncontrollably. My father continued.

“The next day, April 27, 1913, Grandmother Fannie’s worst fears were confirmed. Helen Ferguson, their friend and neighbor, came to the house to tell them she had received a phone call about Mary. Their Mary had been found murdered in the basement of the National Pencil Company.

“The company, a four-story granite building plus basement, was located at 37-39 Forsyth Street. It employed some one hundred people, mostly women, who distributed and manufactured pencils. Its windows were grimy. It was dirty. It had little ventilation. Most of the workers were paid twelve cents an hour. It was in fact a sweat shop of the northern, urban variety.

“Mary worked in its second floor metal room fixing metal caps on pencils by machine. Her last day of work had been the previous Monday. She was told not to report back until a shipment of metal had arrived.

“Her body was discovered at three o’clock in the morning on April twenty-seventh, in the basement of the pencil company by the night watchman, Newt Lee. Her left eye had apparently been struck with a fist; she had an inch-and-a-half gash in the back of the head, and was strangled by a cord which was embedded in her neck.”

He shook his head sadly. “Her undergarments were torn and bloody and a piece of undergarment was around her hair, face, and neck. It appeared that her body had been dragged across the basement floor; there were fragments of soot, ashes, and pencil shavings on the body and drag marks leading from the elevator shaft.

“There didn’t seem to be any skin fragments or blood under her fingernails, which indicated she hadn’t inflicted any harm on whoever did it.

“Two scribbled notes were found near her body. They were on company carbon paper.”

Here, my father got up and walked across the room to the secretary against the far wall, opened the desk flap, reached in and retrieved a sheet of paper, and returned to his chair near the window. He handed me the sheet. It was a photostatic copy of two nearly-illiterate notes:

Mam that negro hire down here did this i went to make water and he push me doun that hole a long tall negro black that hoo it was long sleam tall negro i wright while play with me.

he said he wood love me and land doun play like night witch did it but that long tall black negro did buy his slef.

My father sat silently while I read the notes. When he continued, his voice was almost hoarse. “When they went up to tell William Jackson Phagan—now, that’s your grandfather’s grandfather, he said—my daddy remembered it word for word: ‘The living God will see to it that the brute is found and punished according to his sin. I hope the murderer will be dealt with as he dealt with that tender and innocent child. I hope that he suffers anguish and remorse in the same measure that she suffered pain and shame. No punishment is too great for him. Hanging cannot atone for the crime he has committed and the suffering he as caused both too victim and relatives.’”

My father swallowed hard a couple of times. After a while he continued.

“Mary was buried that following Tuesday,” he said. He suddenly began to quote the newspaper account of little Mary’s funeral service. He’d committed it to memory. “’A thousand persons saw a minister of God raise his hands to heaven today and heard him call for divine justice. Before his closed eyes was a little casket, its pure whiteness hidden by the banks and banks of beautiful flowers. Within the casket lay the bruised and mutilated body of Mary Phagan, the innocent young victim of one of Atlanta’s blackest and most bestial crimes.’

“’L. M. Spruell, B. Awtrey, Ralph Butler, and W. T. Potts were the pallbearers. They carried the little white casket on their shoulders into the Second Baptist Church, a tiny country church. Every seat had been taken within five minutes, every inch of the church was occupied and hundreds were standing outside the church to hear the sermon.’

“The choir sang ‘Rock of Ages,’ but what everyone heard was Grandmother Fannie, wailing as if her heart would break.

“And,” my father added, “it probably did.”

“’The light of my life has been taken,’ she cried, ‘and her soul was as pure and as white as her body.’

“The whole church wept before the completion of the hymn. The Reverend T.T.G. Linkous, Pastor of Christian Church at East Point, prayed with those at the Second Baptist Church.”

My father continued the words that must be etched in his heart:

“’Let us pray. The occasion is so sad to me—when she was but a baby. I taught her to fear God and love Him—that I don’t know what to do.’

” ‘With tears gushing from his eyes, he found the strength to continue. “We pray for the police and the detectives of the City of Atlanta. We pray that they may perform their duty and bring the wretch that committed this act to justice. We pray that we may not hold too much rancor in our hearts—we do not want vengeance—yet we pray that the authorities apprehend the guilty party or parties and punish them to the full extent of the law. Even this is too good for the imp of Satan that did this. Oh, God, I cannot see how even the devil himself could do such a thing.”

“’Fannie Phagan Coleman controlled her crying when he spoke of the criminal and WJ. Phagan, Mary’s grandfather, exclaimed: “Amen.”

“’ “I believe in the law of forgiveness. Yet I do not see how it can be applied in this case. I pray that this wretch, this devil, be caught and punished according to the man-made, God-sanctioned laws of Georgia. And I pray, oh, God, that the innocent ones may be freed and cleared of all suspicion.”

“’With hearing this, Mary’s Aunt Lizzie let out a piercing scream and collapsed and she was taken home,” my father interjected.

“Mothers,”’ Dr. Linkous declared, “I would speak a word to you. Let this warn you. You cannot watch your children too closely. Even though their hearts be as clean and pure as Mary Phagan’s, let them not be forced into dishonor and into the grave by some heartless wretch, like the guilty man in this case.

“’ “Little Mary’s purity and the hope of the world above the sky is the only consolation that I can offer you,” he said, speaking directly to the bereaved family. “Had she been snatched from our midst in a natural way, by disease, we could bear up more easily. Now, we can only thank God that though she was dishonored, she fought back the fiend with all the strength of her fine young body, even unto death.

“’ “All that I can say is God bless you. You have my heartfelt sympathy. That is all that I can do, for my heart, too, is full to overflowing.”

“’Mary’s grandfather, W.J. Phagan, sat motionless as the tears streamed down his face while the brothers of Mary—Benjamin, Charlie, and William Joshua—comforted their sister, Ollie.’”

My father continued in his own words. “After the sermon, they opened the little white casket and the crowd viewed the body of the little girl with a mutilated and bruised face. The tears watered the flowers that surrounded her.

“They carried the casket out to the cemetery. J.W. practically carried Grandmother Fannie out; Dr. Linkous helped. Mary’s sister, Ollie, and her brother Ben, now a sailor on the United States ship Franklin, were behind them, while the smaller brothers, Charlie and Joshua, brought up the rear.”

The account of the funeral service went on:

“’ “Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The Lord hath given, the Lord hath taken, blessed be the name of the Lord,”’ but no words expressed by Dr. Linkous could heal the wounds in their hearts, and as the first shovel of earth was thrown down into the grave, Fannie Phagan Coleman broke down completely and wailed: “She was taken away when the spring was coming—the spring that was so like her. Oh, and she wanted to see the spring. She loved it—it loved her. She played with it—it was a sister to her almost.” She took the preacher’s handkerchief and walked to the edge of the grave and waved the handkerchief. “Goodbye, Mary, goodbye. It’s too big a hole to put you in, though. It’s so big—big, and you were so little—my own little Mary.”

My father stopped. The papers slid to the floor. His eyes were filling up.

I stopped, too. Bursting as I was with questions about the trial of Leo Frank and its aftermath, I could not bring myself to cause my father further pain that day. I felt guilty for the upset the memories he’d dredged up on my behalf had already caused him.

As if reading my thoughts, he turned to me: “It’s all right, Mary. You should know the whole story. But—” he’d blinked back the tears, but his smile was tremulous—“not today.”

A few days later, we sat down again. This time I started right off with the questions:

“Daddy, how did Grandmother Fannie stand up while the trial was going on?”

He told me that she was to be the first witness called to the witness stand. She tried to compose herself; her tears were flowing freely down her cheeks and she was sobbing as she gave her statement:

“’I am Mary Phagan’s mother. I last saw her alive on the 26th of April, 1913, about a quarter to twelve, at home, at 146 Lindsey Street. She was getting ready to go to the pencil factory to get her pay envelope. About 11:30, she had lunch, then she left home at a quarter to twelve. She would have been fourteen years old on the first day of June, she was fair complected, heavy set, very pretty, and was extra large for her age. She had on a lavender dress trimmed in lace and a blue hat. She had dimples in her cheeks.’

“When Sergeant Dobbs described the condition of Mary’s body when they found her in the basement, when he stated that she had been dragged across the floor, face down, that was full of coal cinders, and this was what had caused the punctures and holes in her face, Grandmother Fannie had to leave the courtroom,” my father said.

Now it was I who had to compose myself. I was now starting to feel the pain and agony that all the family had felt for years.

“When the funeral director, W.H. Gheesling, gave his testimony, he stated that he moved little Mary’s body at four o’clock in the morning on April 27, 1913. He stated that the cord she had been strangled with was still around her neck. There was an impression of about an eighth of an inch on the neck, her tongue stuck an inch and a quarter out of her mouth.”

“Daddy, was Mary bitten on her breast?”

“Yes, but there was no way to prove it because certain documents have mysteriously disappeared.”

“Who besides Grandmother Fannie attended the trial?”

“Other than Grandmother Fannie, all the immediate family, including your grandfather and Mary’s stepfather, were present every day. Mary’s mother and sister were the only women, along with Leo Frank’s wife and mother, who were permitted in the courtroom each day.”

“Daddy, why didn’t you tell me about Leo Frank’s religious faith?”

“His religious faith had nothing to do with his trial.” “What does anti-Semitic mean?”

“It means hatred of the Jews.”

I was surprised that people could hate each other because of their faith. “How do you become prejudiced?” I asked.

“You have to be taught to be prejudiced, to walk, talk, just about everything in life that is worth anything. Prejudice, I found out, isn’t worth a nickel, but can cost you a lifetime of grief and sorrow.”

“Daddy, what about the courtroom atmosphere?”

“According to your great-grandmother, Judge Leonard Roan maintained strict discipline in his court at all times and would not tolerate any disturbance. Judge Roan had the authority to make a change of venue if he in any way felt threatened: he made no change of venue. Neither Leo Frank or his lawyers asked for a change of venue.

“The newspapers gave a daily detailed report on the court proceedings, and there were many ‘extras’ printed each day. Not one newspaper ever reported any of the spectators shouting ‘Hang the Jew’ nor did I ever hear that any member of our family made that or any similar statement. Judge Roan was considered by all to be more than fair. The Atlanta Bar held him in high esteem for his ability in criminal law. Otherwise he would have never been on the bench.”

“Was Leo Frank defended well?”

“Leo Frank’s lawyers were the best that money could buy. He had two of the best criminal lawyers in the South, Luther Rosser and Reuben Arnold. I have been told that Rosser’s fee ran well over fifteen thousand dollars. In those years that was a small fortune. These lawyers were the most professional and brilliant lawyers the South had to offer. But the defense these brilliant lawyers were to offer was not good enough to offset Hugh Dorsey’s tactics. If there was any brilliance at that trial, it was Hugh Dorsey’s. The people of Georgia were so impressed by him that he was later rewarded with the biggest prize in state politics: he was elected governor of Georgia.”

“What was meant by Leo Frank being a Northerner and a capitalist? Did these facts have any bearing on the trial?”

My father reminded me about the War Between the States, what had caused it, and that it had been over for only forty-eight years by 1913. He explained how the carpetbaggers had come South to run the country and the awfulness of life under their rule. From that time on, he said, anyone from the North was called a Northerner.

“Leo Frank was born in Texas, but shortly thereafter his family moved to Brooklyn, New York. He was a graduate of Cornell University and he was given the job of superintendent of the National Pencil Company. As for being a capitalist, he did come from a family that was wealthy by the standards of those days. But, as my father pointed out, the hope of any aspiring productive person is to become a capitalist in his own right. In 1913, however, it meant a lifestyle that few people could maintain. And that bred resentment.”

Then I asked, “What is a pervert?”

My father made me get the dictionary and look up the meaning with him. I was not satisfied with the meaning. My father then explained that sexual perversion is something our society does not accept as normal.

Today, this charge will outrage any segment of society. In 1913, anyone who dared to make that charge had better have been prepared to die for it.

“Daddy, why did Governor Slaton commute Leo Frank’s sentence?”

“This is one question that our family still asks today. We do not accept Governor Slaton’s explanation in his order. There had to be something else. No man will willingly commit political suicide; but he did just that with the commutation order. I’ve done some research on my own, but I know no more today than my grandmother did back in 1915. I’ve found certain things about Governor Slaton that are hard to accept but are facts.

“The Atlanta newspapers of 1913 show the law firm of Rosser & Brandon, 708 Empire, and the law firm of Slaton & Phillips, 723 Grant Building, as merging. Then the 1914 Atlanta Directory shows the law firm of Rosser, Brandon, Slaton & Phillips, 719-723 Grant Building. They were also listed in the Atlanta Directory in 1915 and 1916. Slaton was a member of the law firm that defended Leo Frank.

“Governor Slaton was a man that Georgia loved and admired until June 21st, 1915. Then love turned to hate. The people believed that Governor Slaton had been bought. His action caused the people of Georgia to take the law into their own hands, to form a vigilante group and seek justice that they believed had been denied them.

“Governor Slaton had Leo Frank moved from Atlanta for his own protection. He was moved to the Milledgeville Prison Farm, just south of Macon. The vigilante group travelled by car, Model T Fords, and removed Frank from prison. All of them were respected citizens. They called themselves the ‘Knights of Mary Phagan’ and this group later became the impetus for the modern Klu Klux Klan.

“Remember, there were no paved roads in those days. This trip was made at night. Not one guard was hurt, not one shot was fired, not one door was forced. The prison was opened to them. Many in Georgia felt that justice was being done! It was the intent of the vigilantes to take Leo Frank to the Marietta Square and hang him there. Dawn caught up with them before they could reach Marietta. They stopped in a grove not far from where little Mary was buried. Then they carried out his original sentence, ‘to be hung by the neck until dead.’”

Shaken, I asked, “Daddy, were there any Phagans at the lynching?”

He gave me a simple answer. “No! And, everyone knew the identity of the lynchers. But not one man was charged with the death of Leo Frank, not one man was ever brought to trial.”

The next question I asked upset him tremendously: “How do you feel about the lynching, Daddy?”

He related to me what his father had felt when he had talked about the lynching. Grandfather felt that justice had been served—and so did the rest of the family.

But I would not let up. “But how do you feel, Daddy?”

“I feel the same way my family did, justice prevailed.” To understand the actions that these men took on August 17, 1915,1 would have to try and transport myself to those times, he said. “You must try to understand what they felt, what would drive them to take the lav/ into their own hands. You must not try to judge yesterday by today’s standards. By doing this, you are second-guessing history and no one, but no one, has ever been able to do that.”

“Daddy, how about Jim Conley? What part did he have in the death of little Mary Phagan?”

My father said that, reportedly, for the first time in the history of the South, a black man’s testimony helped to convict a white man. The best criminal lawyers in the South could not break this semi-literate black man’s story. The circumstantial evidence and Jim Conley’s testimony caused Leo Frank’s conviction for the murder of little Mary Phagan.

“Your grandfather told me—and this can be confirmed by my sister Annabelle—that he had met with Jim Conley in 1934, in our home, to discuss the trial and the part Conley had played in helping Leo Frank dispose of the body of little Mary.” My father became adamant: “There is no way my father would have let Jim Conley live if he believed that he had murdered little Mary.”

My father then related the conversation that my grandfather told him had taken place. He said to Jim Conley, “Let’s sit down and talk awhile, Jim.”

And Jim said, “OK.”

My grandfather then said, “I want to know how you helped Mr. Frank.”

Jim said, “Well, I watched for Mr. Frank like before and then he stomped and whistled which meant for me to unlock the door and then I went up the steps. Mr. Frank looked funny. He told me that he wanted to be with the little girl, she refused and he struck her and she fell. When I saw her, she was dead.”

Grandfather asked, “But why did you help him if you knew it was wrong?”

And Jim said, “I only helped Mr. Frank because he was white and my boss.”

“Were you afraid of Mr. Frank?” my grandfather asked.

Jim answered, “I was afraid if I didn’t do what he told me—him being white and my boss, that I might get hanged. [At that time, it was common for blacks to be hanged.] So, I did as he told me.” Grandfather then asked, “What did you do after you saw that little Mary was dead?”

There are, my father grinned, two versions of that meeting: his sister Annabelle’s and his father’s—my grandfather’s.

The version my Aunt Annabelle told him was that she was coming out of a grocery store and saw their father, William Joshua Phagan, Jr., and a black man walking (she said “nigger”) down Jefferson Street towards the house.

She said to her father:

“Daddy, what are you doing with that nigger man?”

Grandfather said, “Now, don’t you know who this is?

“No, I don’t,” Annabelle said.

And Grandfather said, “This is Jim Conley.”

“Oh, this is the man who helped kill Aunt Mary,” she exclaimed.

Then Jim Conley said, “No, I didn’t kill her but I helped Mr. Frank. I was to burn the body in the furnace but didn’t.”

They went inside the house and talked about an hour in the kitchen.

Annabelle was in the other room watching her brothers (Jack and my father) and her sister Betty.

My father also remembers that his father continually questioned Jim Conley about why he helped Mr. Frank. He recalled that his father got emotional and at times had to hold back the tears.

Jim said, “I got scared. Like I said before, I had to help Mr. Frank—him being white and my boss. Mr. Frank told me to roll her in a cloth and put her on my shoulder, but she was heavy and she fell. Mr. Frank and I picked her up and went to the elevator to the basement. I rolled her out on the floor. Then Mr. Frank went up the ladder and I went on the elevator.”

“Did Mr. Frank tell you to burn little Mary in the furnace?” my grandfather asked.

“Yes, I was to come back later but I drank some and fell asleep,” Jim said.

Then Grandfather said, “Jim, I believe you because if I didn’t I’d kill you myself.” Then, my father recalls clearly, Grandfather and Jim Conley went out together for a drink.

That was all my father could remember.

“How is it, Daddy, that a black man would help someone dispose of a body?”

“Remember the times,” my father said. “In those years, a black would do almost anything his boss told him to do. His life depended on whatever the white man decided. Lynchings were taking place almost daily in the South. Jim Conley was a black man in Atlanta in 1913, one who could read and write, but more importantly, he was not simple. He was a man who would do what any man would do to stay alive: he would mix the truth with lies self-consciously, knowing full well that his life was at stake.” My father shook his head. “He would give four different affidavits.

“Here was a man that knew he was walking on a red-hot bed of cinders. He knew that no matter which way he turned he would be burned. Conley returned to the pencil factory with the Atlanta detectives and showed them how he had found the body of little Mary in the metal room. How he had moved the body, tied up with some cloth, with the help of Leo Frank. How it took both of them to move her body to the elevator. Once in the basement, Conley said, he rolled the body out on the floor. Then he stated that Leo Frank went up the ladder, to be on alert for anyone coming into the factory.”

Here I asked, “Does this explain why little Mary was dragged face down across the basement?”

“Yes,” he said. “It seems logical in that one man could not carry her body without help. So she was dragged.” “But, Daddy, why would Jim Conley do this knowing full well that he was now mixed up in the murder of little Mary? He must have felt that his actions could cost him his life.”

“Jim Conley did know what he was doing, but there were two factors that outweighed his sense of righteousness: fear and money! Fear of the white man and greed for money. And this is what he later told my father when they met.”

The last thing I wanted to know was a question that my father had asked his father over twenty years ago. “Why has the Phagan family taken a vow of silence?”

“Grandmother Fannie made a request that everyone not talk to the newspapers. Her request was honored. It’s that simple.”

I thought over my father’s words for quite some time. His was the Phagan family’s story of little Mary Phagan.

It was some time before we sat down again to talk about the shadow of Mary Phagan and how her legacy had affected his life. But one summer morning my father sat down beside me wanting to talk about his grandmother—little Mary’s mother.

“I recollect that many times I woke up in Grandmother Fannie’s bed trying to figure out how I got there beside her. My grandmother and step-grandfather, I’ve been told, loved me very much, and they would come to our house and while I was asleep, would take me in their loving arms, and take me home with them.

“Their daughter, Billie, my aunt, would have been little Mary’s half-sister. Billie was a teenager whom I remember as a beautiful girl, who showed me a lot of love and care. It was Billie’s job to take care of me while I was staying with my grandparents. She was as firm as she was beautiful. To her I was a small brother. At lunch time, I was given the choice of a sandwich or soup. Billie would allow me to have mustard on my sandwich and to this day each time I eat a sandwich with mustard on it, I think of Billie.

“Grandfather Coleman had a small country store with a gas pump, and one of my greatest pleasures was when I was turned loose in that treasure house and was allowed to have anything that I wanted. What treasures I saw in that country store! It can only be appreciated by another child. What to choose was the biggest problem I had to face in those early years, and sometimes I would spend a whole minute, which to me was a lifetime. Grandfather Coleman was always there to guide me and help me in making my choice. Over fifty years have passed but those days are vivid to me now as they were then.

“Grandmother Fannie was a very special person to me. I remember her talking to me about her daughter, little Mary. I could never understand why there were tears in her eyes when she talked about little Mary.

“It’s very hard on a small child to watch one’s grandmother cry and not being able to understand what’s really going on. I took what I felt was the only course open to me: I put my arms around her and told her that I loved her. Then, more tears flowed and she hugged me even harder.”

My father stopped and sat, his chin in his hand, looking out the window. I could hear the calls of the birds clearly.

“Daddy,” I said, “if you want to stop—”

“No,” he said, “I don’t want to stop.” He went on.

“In 1937 my parents bought their first home in Atlanta, 760 Primrose Street Southwest. It had three bedrooms, a living room, kitchen, and dining room connected to it and one bathroom with no shower. My dad worked in the cotton mills as a weaver and my mother opened a hamburger, hot dog, and sandwich stand on the corner of Hunter and Butler Street which was only a half of a block from the ‘big rock jail.’ This was the same jail that Leo Frank was held in, known as ‘The Tower.’ I was a student at Slaton Grammar School, which was named after the father of the governor who had commuted Leo Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment.

“Grandmother Fannie meant more and more to me as I was starting to understand what life is about. After all,” his eyes twinkled, “it had to happen sometime! And the question was starting to come up, no matter where I was: ‘Are you, by any chance, kin to little Mary Phagan?’

“’Of course,’ I replied everytime, ‘she was my aunt.’ This generally resulted in more questions about little Mary. I would answer those questions the best I could from what I could remember from stories that I’d heard from members of my family. People would then relate them to me on what they had heard from their pasts. The one question they always asked was ‘How did little Mary’s mother take her daughter’s death?’ And this invariably brought a silence in the group of people around me. I came to understand that this question would cause adults to hang onto every word I said. And just as invariably I’d feel humongously sad as I tried to put into words how my grandmother felt. Time had not healed the loss of her daughter. And maybe it never would.

“Little Mary, you understand, was the youngest of five and because she was the last child, she was doted on by all, even her grandfather, W. J.

“Grandmother Fannie would describe to me how she would comb little Mary’s hair and put it up in pigtails, dress her up in her finest clothes to go to church. A small child is always beautiful to its parents, but little Mary was really beautiful—and she was going to be a real beauty when she grew up. As she approached her teenage years, there was no doubt that she was going to be a beautiful young woman.”

My father looked at me intently. “As I’ve said—and others have said—lots of times before: just like you.”

A strange feeling began to rise inside me: a mixture of gratification—I’m as lovely as she was—pride—this is my inheritance—and apprehension. Not that I thought I’d meet the same fate as my namesake, of course, but I did wonder what reverberations there would be from our bond. The vow of silence notwithstanding, my name—and appearance—were already causing these reverberations.

I smiled at my father. “Whatever it is, I believe I can deal with it.” He patted my shoulder and continued his memories.

“School was not mandatory back then, and all members of a family that were old enough to work in factories would do so. Money was not easy to come by. Little Mary did attend school and was a good student, according to my grandmother. She had a lively imagination and wanted all the things that any young girl wanted in those days: ribbons or a special comb for her hair. And while all monies went to help the family, her being the youngest allowed special favors.

“By the time I was eleven, I began to ask questions about my aunt. My best source of information was my father, William Joshua Phagan, Jr., who was known to the family as ‘Little Josh.’” My father broke into a grin. “No one ever accused the Phagans of being too tall. Anyway, I questioned him—as you’re questioning me—about everything that had happened in those days. Tears would come to his eyes, too, and he would talk about his sister very slowly. They were only one year apart: he was born in January 1898, and little Mary was born in June 1899. He felt a lot of pride about being the older brother to his sister to whom he was a shining white knight. There were slow pauses. He took time to hold back his tears. I could feel the pain that he was experiencing—even though I didn’t understand it then.

“Dad told me how Grandmother Fannie had everyone put on his or her best clothes for church on Sundays and how everyone had a hand in helping little Mary to dress up. How pretty she was and the pleasure it brought to see her dressed in her best clothes.

“I don’t remember Ollie too well; we didn’t visit too much in those days that Dad worked for the cotton mills. However, when we visited it was usually for the whole weekend. What times those were! When the Phagan family got together it was like a picnic, with all the food and stuff that was on hand to eat.”

I tried to picture the family gathering in my mind. I concentrated very hard. I wanted to visualize the Phagans in a happy, relaxed atmosphere—playing, joking around, eating to their heart’s content, and telling stories.

My father broke into my thoughts: “Before the first day was over, everyone would turn to the subject of little Mary. I would sit quietly and listen to the stories. Fascinated as I was, I could still feel the tension in the air as each would tell some small detail about little Mary. I came to know her not as an aunt but as a special person who had lost her life in a brutal attack by Leo Frank, who was convicted of that crime by a jury of his peers in a court of law in Fulton County, Georgia.

“Grandmother Fannie often told us about the death of her husband, William Joshua Phagan, who had fathered her five children. He had died in February, 1899. Life in those days was real rough on a widow with children. Then she would talk about J.W. Coleman, whom she married in 1912. This was the man I was to know as my grandfather. Then the stories would turn back to little Mary. And the tension would start to build up again.

“Grandmother would usually start her story about that Saturday, Confederate Memorial Day, when little Mary had left home to go to town for her wages and to see the parade. She would tell about her new lavender dress and silver mesh bag that she carried, the ribbons in her hair and her parasol. The area they lived in then—the Bellwood subdivision of the Exposition cotton mill area—is only a memory today: it’s where Ashby Street crosses Bankhead Avenue and Ashby goes on into Marietta Street.

“By the time Grandmother got to where little Mary took the English Avenue streetcar that was to take her downtown to the National Pencil Company, her tears were usually too much for her, and her story would come to a close, since she could no longer continue. Members of the family would quietly take grandmother into the house so that she could compose herself. This always left me in a state of confusion.

“Later, the war came. Greatuncle Ben was in the Navy.” My father sighed. “The Phagan family, like the rest of the country, began to drift apart. The war began to push everything else to the rear of our minds. People were starting to work as many as six days a week. Family gathering was to become a thing of the past. But my family still spoke about little Mary, about how pretty she had been, and all. I felt for the first time in my life that I too had lost someone that was very real to me. For the first time I also came to feel what grief felt like.

“But gradually, there was less time for story-telling. My only source of information about little Mary then was my Dad. He would still talk about his sister to me, but these talks got fewer and farther between—although his grief never diminished and it was still hard for him to talk about little Mary.

“At the same time, my curiosity increased, since people would still ask me questions about little Mary. And there was still Fannie, too. Now more than ever, Grandmother would tell me stories about little Mary, how pretty she was and the hopes she had for her. Even today when I look at little Mary’s picture, I can see that my grandmother was right about how pretty she was. I do believe that she would have grown into the beautiful woman that my grandmother expected her to be. The years had not stopped the pain and grief she felt, but perhaps they made them a little more bearable.

“In 1943, when I started junior high school, the old question was asked again: ‘Are you, by any chance, kin to little Mary Phagan?’ As I recall, the teacher was the first to ask, and then, as the week went on, children of my age would start to ask me questions that their families had asked them to ask me. Some even brought articles to school to show me. One kid brought a record, a 78 RPM, that had ‘The Ballad of Mary Phagan’ on it. Fiddling John Carson had written and recorded it. I had heard people sing this song all my life but this was the first time I had heard it on a record. Later in life, I was to come by this record for my family. My mother had bought an RCA radio and record player in the later thirties. I had a collection of records. We held onto the record for years but somehow it was finally lost. We still have that RCA radio and record player, you know. It’s in the basement. It doesn’t work anymore, but one day I’ll probably restore it—just in case I should find that record again of little Mary Phagan.

“During the war years women had to work in the plants and shipyards and they became a vital part of the work force. My older sister, Annabelle, went to work in the shipyards in Portland, Oregon. Even my mother went to work at the Bell Bomb Plant in Marietta, Georgia. Her name, Mary Phagan, really started questions about little Mary all over again. The stories she told us kids generated a closer feeling again with little Mary.

“In 1944, Europe was invaded and that was the beginning of the end of the war there. I joined the Navy in July of 1945, and in August I was sent to boot camp in San Diego, California. My name preceded me in the Navy, because by then books had been written and even movies had been made of little Mary’s murder. ‘Death in the Deep South,’ a fictional book about the murder and its after- math was made into a movie. The movie was called They Don’t Forget,’ and Lana Turner played the part of little Mary. But the names were changed. And the Phagan family remained silent.

“I had learned to play golf at Piedmont Park where I had worked as a caddie, and to my surprise, I was invited to play golf with a group of civilian and naval personnel. Then I found out why I’d been invited. They pelted me with questions about little Mary. What I thought about the case and how did the Phagans feel about the way the public as a whole had treated us. I was only seventeen years old, but I was well versed in the way my family felt, and I managed to give fairly noncommittal replies.

“Later, when my shipmates on the U.S.S. Major DE796 began to ask me questions about little Mary, I turned out to be a storehouse of information on that subject, but again stayed noncommittal as to the family’s feelings. I was to serve aboard another DE, the U.S.S. Fieberling, for about two years, until she was decommissioned.

“Grandmother Fannie passed away in 1947, while I was in the Navy. I made the trip home for her funeral. But when I arrived home, she had already been buried. She was laid to rest beside her daughter, little Mary Phagan. The peace she couldn’t find in life she found, I hope, in death.

“Sometime later I met your mother in Chicago. The year was 1952. It was love at first sight!”

He leaned back in his chair, and his face was suffused in light. His smile was happy and tender. Things hadn’t changed much as far as my parents’ feelings for each other went.

“Anyway,” he smiled, “at the time I was flying to London out of Warner-Robbins Air Force Base in Macon. Being a Georgia boy from Atlanta, I went out of my way to meet all the civilian flight line mechanics at Warner Robbins in Macon. Depot bases use civilian flight line mechanics so that there will be a more stable work force.

“Little Mary had slipped to the back of my mind over the years. When the flight line mechanics learned my name, they began to question me about little Mary. Again, I was reminded of her. All the mechanics and other personnel made sure that I shared lunch with them. They all wanted to hear about little Mary Phagan. Most of them had stories that they had heard from their parents and grandparents to tell about little Mary. It was beginning to dawn on me that little Mary was more than just a passing fancy to Georgians of all walks of life. It was part of their history, like it or not, and they wanted to hear firsthand what the Phagans felt and how they responded to their questions. Unknown to me at that time, this renewed interest in little Mary was to play a major role in the life of another little girl who would be born in June of 1954, but that was almost two years in the future.

“Well, the wedding—and it was a huge one—was in 1953, and we spent our honeymoon in St. Augustine, Florida. Uncle Frank loaned us his car so that we could drive down. We were gone for about seven days, after which we started back to Chicago. The plan was to leave your mother until such time as I could find an apartment for us in Moses Lake, Washington State, where I’d been transferred.

“When I arrived back at Larson Air Force Base, I was informed that I had been selected to attend Flight Engineer School at Chanute Air Force Base in Rantoul, Illinois. Joy heaped upon joy and my cup runneth over! Your mother and I could be together after all! The school was to last for six months.

“We found an apartment near the University of Illinois, in Champaigne-Urbana. This break allowed us time to learn more about each other and how we would spend the years to come.

“It was about this time that the question was asked again about my name by other student Flight Engineers: ‘Are you, by any chance, kin to little Mary Phagan?’ I had not told your mother the story of little Mary.

“I was transferred back to the past again. How did my family feel, especially my grandmother? I had become used to these questions and without breaking stride, I would answer them and continue on with the story that had become a part of my life. I could never understand this interest in a murder that had happened way back in 1913, but of course, tragedy has a way of capturing the interest of its audience as the story teller retells the story from firsthand information.

“As you well know,” my father twinkled, “you were born in June of 1954. Phyllis, your sister, came along in 1956.

“By this time, I had accumulated over two thousand hours of flying in Alaska and was considered to be a cold weather expert. Personally, I’ve always felt that anyone who had flown in the Arctic and survived was a cold weather expert. We were now under a new command, the Military Air Transport Service; undoubtedly the best and biggest airlift armada in the world. We were redesignated the 62nd Military Airlift Wing on January 8, 1956, ‘M.A.T.S., the Backbone of Deterrence.’ It was our motto and creed.

“We were now flying all over the world, in all kinds of trouble spots where there was dire need for airlift. And once again, I found that my name rang bells with those people who were familiar with little Mary Phagan. I got all kinds of messages asking about her past and what relationship I was to her. They followed me wherever I flew, but more so when I was to fly in the South, where my family’s history was well known.

“Your brother James was born in November 1957, during the Lebanon-Beirut troubles which our Wing was flying into.

“By the time you were about four years old, you bore a striking resemblance to your greataunt, little Mary.

“In January 1959 I asked for reassignment and was assigned to the 1608 Military Air Transport Wing in Charleston, South Carolina. When we arrived in Charleston, I was assigned to the 17th Air Transport Squadron.

“The interest your name caused when we signed you up for kindergarten was unreal. People would come up to us and sing ‘The Ballad of Mary Phagan.’ They told me stories that I had never heard before. Then the questions would come: what relationship we were and how had our daughter been named for little Mary? They would say, ‘My, what a pretty girl!’ and ‘She looks just like little Mary.’

“Your brother Michael was born in September 1959, in Charleston. Soon after that, we all went to Japan and Hawaii, and returned to the continental U.S. in 1964, to Charleston. And it was there that Mr. Henry, your eighth-grade teacher, asked you if you were related to little Mary Phagan. That must have been pretty difficult for you, Mary.”

I nodded, unable to speak.

“But I’m proud that you want to understand your heritage.”

There are always two—or more—sides to everything. Clearly, the Phagan family believed in Leo Frank’s guilt. But my father again encouraged me to research and investigate the facts for myself. He told me that the trial record spoke for itself. He also pointed out that for my own peace of mind I would have to interpret the facts myself to the best of my ability and to draw my own conclusions.

What was Atlanta really like in 1913? I still wondered: Did Leo Frank get a fair trial? Did the shouts that came through the open windows in the courtroom have any influence on the jury? Did his being Jewish affect the trial outcome? Why were eleven witnesses who were employed at the National Pencil Company not cross-examined by the defense as to Frank’s lascivious conduct? Was Jim Conley the actual criminal?

These unanswered questions remained with me throughout my high school years. At the same time that my resolve to learn all I could about my greataunt intensified, my aspirations as to a future career became both evident and important to me. I wanted to teach blind and visually impaired children. I began exploring opportunities. And my senior year was especially gratifying. Since I finished classes early in the day, I was allowed to leave campus for joint-enrollment at a college or for employment, and my counselor, Mrs. Drury, had discovered that McLendon Elementary School, not far from the high school campus, would love to have me as a volunteer.

I spent ten hours a week at McLendon, and it made my mind up definitely: I was going to teach the blind and visually impaired.

The star in my crown that year was the award I received from the DeKalb County Rotary Clubs: the Youth Achievement Award. I was the very first recipient of this award, and the only disappointment was that my blind students couldn’t read it. But I read it to them.

I’d applied to and been accepted at Flagler College in St. Augustine, Florida. I was to start classes in September, 1972.

And, yes, at that moment I hoped that the story of little Mary Phagan would be left behind.

So I consciously left the unanswered questions in Atlanta. But my subconscious was still busy with them, and they came with me to Florida, “haunting” me even as I was sleeping.