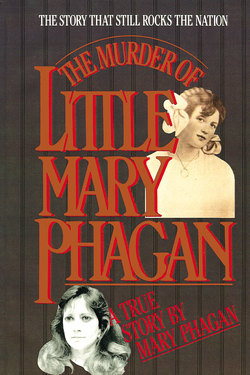

Читать книгу Murder of Little Mary Phagan - Mary Phagan - Страница 9

ОглавлениеAfter they left, I stood there feeling again all the conflicting emotions which I could not resolve or forget. My mind spun back fifteen years.

I was thirteen. We were living in Charleston, South Carolina, where my father, the First Sergeant of the 17th Air Transport Squadron, was stationed. Mr. Henry, my eighth-grade science teacher at R. B. Stall High School, registered astonishment when I told him my name was Mary Phagan. “You know,” he said, “there was a little girl who was murdered in Atlanta years and years ago who had the same name as you. Are you, by any chance, related to her?”

I told him I didn’t know.

That conversation disturbed me. I became curious. Was there really another Mary Phagan?

During recess some of my classmates taunted me. “Are you that dead girl’s reincarnation?” Another called out, “Are you the little girl who had been murdered?” and ran away.

I cried all the way home from school. My father happened to be home. “What’s wrong?” he asked when he saw my tear-stained face.

“I want to know who the little girl named Mary Phagan that was murdered was,” I said, trembling. “Am I related to her?”

He put his arm around my shoulders, walked me into the kitchen, and sat me down at the table in the sunny alcove.

He poured two glasses of milk, brought them to the table, and sat opposite me. The afternoon sun played up the reddish tints in his light brown hair, worn in a severe military crewcut, and glinted off his military-issue glasses.

“Yes, you are related to little Mary Phagan,” he said solemnly. “She was your grandfather’s sister. She would have been my aunt. You are her greatniece and are named for her.”

Gently, he told me the outline of the story of Mary Phagan. That she had caught the English Avenue Street Car the morning of Saturday, April 26, 1913, Confederate Memorial Day, to go to the National Pencil Company where she had worked in downtown Atlanta to pick up her wages of $1.20. She had made plans to stay and watch the parade. Governor Joseph M. Brown and other dignitaries were to share the reviewing stand. It was a legal holiday that the South still celebrated then. The War Between the States had been over for only forty-eight years. There were still some surviving Confederate veterans.

“That day would change the lives of everyone it touched.

“Tom Watson would reflect the mood of us Georgians in his magazine and newspaper. He would be elected to the United States Senate, and his statue placed in front of the Georgia State Capital Building. Solicitor Hugh M. Dorsey would ride right into the Governorship of Georgia.”

As my father leaned back, the sunlight turned his hazel eyes to green. “Your grandmother Fannie Phagan Coleman remembered that day the rest of her life,” he said. “Little Mary was dressed in a lavender dress that her Aunt Lizzie had made for her. She carried a parasol and a German silver mesh bag. She had ribbons in her hair that tied her long reddish hair up. She was a beautiful young child—” my father paused, “—like you.

“Little Mary entered the pencil factory about noon that day,” he continued. “What happened then, no one will ever really know. Newt Lee, the night watchman, found her body in the basement next to the coal bin that Sunday morning at about 3:00 a.m. She had been brutally raped and murdered. Newt Lee was a Negro, and, remember, in 1906 Atlanta had one of the country’s worst race riots. So right then he feared for his life. He would have been afraid to lie even if he had wanted to. He ran up to the telephone and called the police. Two notes were found by her body but Mary did not write these notes, according to Grandmother Fannie.

“Grandmother Fannie had been expecting Mary back home that evening after the parade. Sundown came and still no little Mary. My stepgrandfather went downtown to try to locate anyone that could give him information on little Mary’s whereabouts. No luck. It would be the next day, the twenty-seventh of April, before they were told that little Mary had been found dead. The family was terrified. Shocked. She was so young. And she’d been violated.

“Little Mary’s body was taken to Bloomfield’s, a local undertaker, which was also used as Atlanta’s morgue. The funeral was held that Tuesday, April 29, 1913. Her casket was surrounded by flowers—the flowers were expressions of the whole state’s sympathy to the family. She was laid to rest that day in Marietta City cemetery.

“Leo Frank, the supervisor of the factory, was charged with the murder. His trial started on the twenty- eighth day of July that year. The case became famous because it was reportedly the first time in the history of Georgia and the South that a black man’s testimony helped to convict a white man.”

Looking closely at me, my father realized that I did not understand all he was telling me. And so he simplified the story as much as he could.

As soon as we got up from the table I went upstairs to my room and examined what I saw in my mirror: Pretty? Was I?

Satisfied with my father’s explanation, I relaxed a bit. It was just a coincidence that Mr. Henry, my science teacher, had known the story of little Mary Phagan, I told myself. I was positive that I would never be asked that question again.

That was in 1968. My father decided to retire from the United States Air Force after serving some twenty-two years in that same year. Then he went to work for the United States Post Office as a letter carrier in Charleston.

During my summer vacation that year I went to Chicago to visit relatives with my grandmother, Frances Petullo Mastandrea, who had lived with us for five years. A few weeks after our arrival in Chicago, my parents called to say the family was moving to Atlanta. “Our family is in Atlanta,” my father said, “and my parents are getting older. I want us to know them as we do Grandma Frances.”

He was right. We never really knew any of our family. And I was ready to settle down and live somewhere for more than a couple of years. I was excited as we arrived at our new home in DeKalb County, on the outskirts of metropolitan Atlanta and close enough to my grandparents in Atlanta.

It was a nice suburb in which to raise a family, and the high school, Shamrock, was the best the area had to offer.

When school began, I soon learned that making friends might be difficult: most of the cliques had gone to school together since kindergarten. That was hard for me to imagine. I had never had a friend more than a few years; to have a lifetime friend seemed impossible.

The first day, the teachers called out our names, glancing at each student in order to associate names and faces. To my amazement, most of my teachers asked me that question: “Are you, by any chance, related to little Mary Phagan who was murdered here in Atlanta? Are you her namesake?”

I was horrified. What was the truth about my great-aunt? Who knew the whole story?

I decided to ask my grandfather, William Joshua Phagan, Jr. about his little sister. Of all people in our family, he’d be the one to know about the pretty girl for whom I’d been named.

But my grandfather was beginning to show his age then. His light blue eyes reflected the continual tiredness he felt. His balding head glittered in the sunlight. He’d had a stroke earlier and his communication skills were hampered, so I decided to wait until the right moment to ask him my questions.

One day, to everyone’s surprise, my grandfather came out with little Mary’s picture and pointed to me. As he looked at the picture and then me, he sobbed, and as he tried to find the words, nothing came out but low sobs and wailings. I knew then I could never ask him any questions about little Mary.

I decided to ask my father if he could tell why he named me after little Mary.

And he was ready for the question. “I had determined, almost from the day your mother and I were married, that we would name our first girl child after your greataunt, little Mary Phagan. This was my tribute to my father. Little did I realize the impact this would have on you. And, yes, I wonder if I knew then what I know today if I would have named you after little Mary.

“Your greataunt had been born on June 1 and you on June 5. As soon as you were big enough, I would take you with me on Saturday morning when my friends and I went out for coffee. You were my constant companion when I was not out flying, and I took a great deal of pleasure in teaching you the things that all young children have to learn. A wife, a child, flying, what more could a man want?

“Some of my friends would from time to time make comments about your size. You have always been petite, and it seemed you were taking after your greataunt, little Mary: she never was to be over four feet eleven inches. In sheer desperation, I would ask, ‘Well, what do you expect out of Shetland Ponies, stallions?’ This method worked with the adults.

“When you were about four years old, you bore a striking resemblance to your greataunt, little Mary. But at that early age, it made no difference or impression on you.”

When I was four and a half, in January, 1959, my father had asked for reassignment and was assigned to the 1608 Military Air Transport Wing in Charleston, South Carolina. When we arrived in Charleston, he was assigned to the 17th Air Transport Squadron. He continued:

“The interest your name caused when we signed you up for kindergarten was unreal. People would come up to us and sing ‘The Ballad of Mary Phagan.’ They would tell me stories that I had never heard before. Then the questions would come: what relationship we were and had our daughter been named for little Mary? They would exclaim about what a pretty little girl you were and that you looked just like little Mary.”

In January 1960 my father was presented with an Individual Flying Safety Award and was assigned to the 1503rd Air Transport Wing in Tachikawa Air Base, Japan. By then I had a sister and two brothers.

“Tachikawa was our home for the next three years,” he told me. “These years we were flying mostly into Korea and the Phillippines. During this time, few questions were asked about little Mary.

“I extended my tour for another year in order to go to Hawaii. During those years out of the country, little Mary had gently slipped to the rear of my mind. In December 1964 I was promoted to Master Sergeant. Now it was time to return to the continental United States, which we did in July 1965.

“Your life took a turn then that I had not foreseen. The day you came home from school crying and asking me about little Mary was a day I would never forget. I had mixed emotions. I wanted you to know your legacy, but on the other hand, I became frightened for you. I had hoped that you would never encounter discourteous people and I feared that your legacy would submit you to this.”

Daddy continued, “You carry a proud name, one that is instantly recognized not only here in Georgia but all across this great country of ours. Hold your head high, stand proud, face the world, let them know that you are Mary Phagan, the greatniece of little Mary Phagan.”

It was then I learned that a vow of silence had been kept by our family for close to seventy years. It had been imposed on us by Fannie Phagan Coleman, Mary Phagan’s mother, at the time of little Mary’s death.

The murder, the trial of Leo Frank, and his lynching has deeply affected the lives of all involved. All the principals in the trial are dead now—and the obituary of each of them mentioned their connection to the murder of little Mary Phagan.

My family had hoped that the .lynching of Leo Frank would be the final ending of the horrible tragedy; that they could finally continue their lives; that the pain would ease. It hasn’t.

The legacy left to me is a difficult one but I have had to accept it. Until recently, I discussed little Mary Phagan only if I was asked: “Are you by any chance related to little Mary Phagan?” But, to my surprise, I have been asked that question all my life—both inside and outside of Georgia.