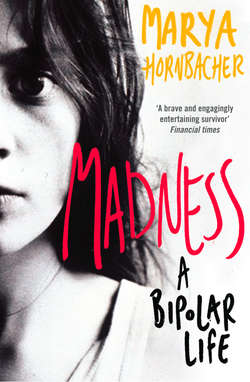

Читать книгу Madness: A Bipolar Life - Marya Hornbacher - Страница 15

Minneapolis

Оглавление1990

I am caught. I pace up and down the hospital halls, the eating disorders ward back home, refusing to believe I’m half dead. These doctors are fools, my parents’ terror unfounded. Let me out! I holler. Leave me alone! I scream as the nurses chase me with Dixie cups of Ensure, the evil drink, all calories and fat. They’re trying to make up for what I’m burning while pacing, pacing, pacing the halls, panicked, hyper, locked in. I beat on the doors, crying, yell at my parents, stare at the food they put in front of me six times a day, Get it away, I won’t eat it, you can’t make me.

The doctor tells my parents I’m depressed. I know I’m not. Something else entirely is wrong. But doctors always say people with eating disorders are depressed. His diagnosis ignores my agitation, the fact that I sail up and crash down minute by minute. I guess he has his reasons: the extremity of my anorexia and bulimia is, to say the least, distracting. I have a life-threatening condition. No one—not my parents, not the therapists, and certainly not the doctors—has time to focus on the mayhem of my moods. Their primary goal is keeping me alive. But they’re missing the forest for the trees. (That happens to this day to patients with eating disorders. Doctors zoom in on the havoc that starving, bingeing, and purging wreaks on the body; and while it’s certainly true that some people with eating disorders have depression, the doctors assume that all of them do. So in people with eating disorders but without depression, the symptom is treated, but not the cause, and the physicians end up ignoring the mood disorders that the patients may actually have. The real underlying mental illness runs wild, advancing steadily, irreparably damaging the mind.)

Fuck this! I shout at my parents. I stand up from my chair and say again, Fuck this!

Marya, sit down.

No! I shout. I pace in circles around the room. The other patients and their families watch me from the corners of their eyes. My brain is burning. I stand over my parents, waving my arms. You can’t just keep me here! I scream. What about my civil rights?

You have no civil rights, my mother points out. Not until you’re eighteen.

I’m moving to California, I say.

What are you talking about?

I’ll live with Anne (she’s my father’s first wife), and I’ll go to school and everything.

They stare at me.

It will be totally good for me, I say, honing my argument—this plan has just occurred to me in the last three minutes, but now it is essential, imperative, that I go. It is the most important thing ever in my whole life.

I perk up, suddenly loving and cheerful. It will be totally healing for me, I say. I will totally get better. You won’t have to worry about me. I’ll totally take in the sea air. It’s very centering out there.

California will be perfect. No one will watch me.

I’ll totally take long walks on the beach, I say. I’ll walk in the sunshine and celebrate the rain. I’ll get back in my body. I’ll do yoga. I’ll totally blossom. You see? It’s perfect. It’s just the thing.

My parents look at each other.

A few weeks later, they let me out of lockup, and I’m sitting on a plane.