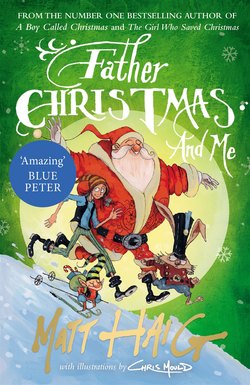

Читать книгу Father Christmas and Me - Matt Haig - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHope Toffee

o get anywhere in Elfhelm you had to walk along a big street called the Main Path. Elves weren’t always very original with their names. For instance, there was another street with seven curves that they called the Street of Seven Curves.

Anyway, as we walked along the Main Path the whole street was bustling with elves. There were clog shops, tunic shops, belt shops. There was something called the School of Sleighcraft on the Main Path too. All kinds of sleighs were there, though none looked as impressive as the one I had ridden on my journey to Elfhelm – the one Father Christmas kept parked in Reindeer Field.

Father Christmas waved at a tall (by elf standards), skinny elf who was polishing a small white sleigh. The sleigh gleamed and looked quite beautiful.

‘Hello, Kip! Is that the new sleigh I’ve been hearing about?’

The elf smiled. It was a small smile. The kind of smile that was surprised to be there. ‘Yes, Father Christmas. The Blizzard 360.’

‘She looks a beauty. Single-reindeer?’

‘Yes, single-reindeer.’

And then Father Christmas started on a long and technical conversation about speedometers and harnesses and altitude gauges and compasses.

He finished their discussion with a question: ‘So you’ll be letting the children ride in it when the school term starts?’

Kip looked worried suddenly. ‘No,’ he said. ‘This isn’t a child’s sleigh. Look at the size of it. This is for bigger elves – grown-ups only.’

Then Mary joined in. ‘Well,’ she said, putting her arm around me, ‘the school is getting a new child this year. A child who is bigger than an elf child. A child who is actually taller than an elf grown-up.’

‘This is Amelia,’ added Father Christmas, ‘and believe me, she is a natural sleigh rider.’

Kip stared at me and turned as pale as snow. ‘Oh. I see. Um. Err. Right. Well.’

And that was it. He went back to polishing his sleigh and we carried on walking along the street.

‘Poor Kip,’ said Father Christmas softly. ‘He had a terrible childhood.’

Every other elf we saw was very friendly and talkative. Mother Breer the beltmaker fitted Father Christmas with a new belt. (‘Oh, Father Christmas, your belly has grown. We’re going to have to make an extra hole.’)

Then we went to the sweet shop and met Bonbon the sweetmaker, who let us taste some of the new things she had been working on. We tried the Purple Cloudberry Fudge and a strong-tasting aniseed-y sweet called Blitzen’s Revenge (named after Father Christmas’s favourite reindeer) and then the Baby Soother.

‘Why is it called the Baby Soother?’ I asked. And then she pointed to her baby – ‘little Suki’ – who had a cute face and pointed ears, and was sitting happily in a bouncy chair, sucking on a sweet.

‘It always works on her,’ said Bonbon.

The most incredible sweet of all, though, was the one called Hope Toffee.

‘Ooh, toffee,’ I said, clapping my hands. ‘I love toffee. What does this one taste of?’

Bonbon looked at me as if I had said something very stupid. ‘It is Hope Toffee. It tastes of whatever you hope it tastes like.’

So when I put it in my mouth I hoped very hard that it would taste like chocolate, and it did taste like chocolate, and then I hoped it would taste like apple pie, and the sweet heated up in my mouth and became exactly like apple pie, and then I thought of the roasted chestnuts I used to eat every Christmas, before Mother had become poorly, and there they were, tender and warm and crumbling like a memory in my mouth. And this last taste, although delicious, also made me feel sad that I didn’t have a mother any more, so I swallowed it and didn’t ask for another one. I had some Giggle Candy instead, which tickled my tongue and made me laugh.

The shop doorbell tinkled and in walked a smartly dressed couple, both wearing red tunics. One of them had glasses and a bald head, and the other was as round as a globe.

‘Ah, hello, Pi,’ said Father Christmas to the one with glasses.

He then turned to me. ‘Pi is your new mathematics teacher.’

‘Hello,’ Pi said, chewing on some liquorice. ‘You’re a human. I’ve heard about human mathematics. It sounds most ridiculous.’

I was confused. ‘I thought mathematics was the same everywhere.’

Pi laughed. ‘Quite the opposite! Quite the opposite!’

And then I was introduced to the other elf, who was called Columbus. ‘I’m a teacher too. I teach geography.’

‘Is elf geography like human geography?’ asked Mary.

But Father Christmas answered on Columbus’s behalf. ‘No. For one thing, in human geography, Elfhelm doesn’t even exist.’

And then we ate some more sweets and bought some to take home and said goodbye to Bonbon and Pi and Columbus and headed out into the street. We walked past a newspaper stand selling the Daily Snow.

‘Oh dear,’ said Father Christmas. ‘There’s no queue . . . No one wants to buy the Daily Snow any more.’

I knew a bit about the Daily Snow. It was the main elf newspaper. It had always been run by an elf called Father Vodol. Father Vodol was a Very Bad Elf. He’d always hated Father Christmas and, when Father Christmas had first arrived in Elfhelm as a boy, had locked him up in prison. You see, Father Vodol used to be the Leader of the Elf Council and had ruled Elfhelm and made everyone fear outsiders, such as humans. But then, when Father Christmas had become Leader, Father Vodol kept running the Daily Snow for years – until last Christmas, when it became clear he’d helped the trolls attack Elfhelm. His punishment hadn’t been prison (elves don’t go to prison any more), it had been to lose the Daily Snow and to go and live in a small house on the quietest street in Elfhelm, which was called Very Quiet Street. It was seen as a punishment to have to live on Very Quiet Street because elves hated the quiet.

The only trouble with the Daily Snow was that since Noosh, the former Reindeer Correspondent, had taken over, two things had happened. First, the newspaper had got a lot better. Second, it had also stopped selling. It seemed that elves preferred it when Father Vodol made up stories and lied about everything.

I am telling you all this now, because it is important for what happens later. But at the time – stepping out of that sweet shop – I had a different worry in my mind.

‘I have never been to a school before. They didn’t teach you anything in the workhouse. All you did was work. And, besides, elf school sounds very strange. How will I fit in?’

‘Oh, but you see,’ said Father Christmas, ‘you underestimate yourself. You were good at riding a sleigh right from the start, weren’t you?’

‘But what if—’

‘Listen,’ said Father Christmas. ‘You don’t have to worry. This is Elfhelm. This is the place where anything can happen. It’s like that sweet you just ate. Whatever you hope to feel, you will feel.’

‘Is life really that simple, Nikolas?’ asked Mary, who called Father Christmas by his first name.

‘It can be,’ said Father Christmas.

And it was easy to feel as positive as him, right then, as we walked down the Main Path. Everything looked happy and bright.

Just then I noticed Father Christmas and Mary holding hands, and I thought it looked a very lovely thing. Maybe the loveliest thing I had ever seen. And I was so overwhelmed with the loveliness of it that I found myself saying what was in my mind, and what was in my mind was this: ‘You should get married.’

Both of them turned around to look at me on that happy, bustling, snow-lined street and looked shocked.

‘Sorry,’ I said, ‘I shouldn’t have said that.’

They looked at each other and burst out laughing.

And Mary said, ‘What a good idea, Amelia!’

And Father Christmas said, ‘The very best idea!’

And that is how Mary Ethel Winters came to marry Father Christmas.