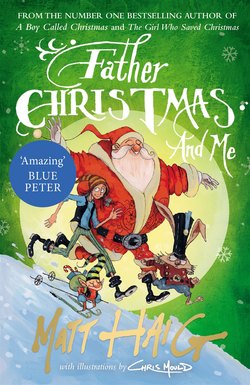

Читать книгу Father Christmas and Me - Matt Haig - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy First Year at Elf School

lves were small but elf children were smaller. Even though I was technically a child I was quite tall by human-child standards, so I was very tall by elf-child standards.

I was always bumping my head on the school doorways, I could hardly squeeze my legs under the desk, and the seat of the chair seemed to be on the floor. The notepads and the crayons were too small. And the toilets – well, the toilets were just ridiculous.

But I did like it that all the classes had names. There was Frost Class and Gingerbread Class and Sleigh Bell Class, and the oldest elves were in Mistletoe Class. I was in Snowball Class.

I sat next to a smiley elf girl called Twinkle who was good at everything. All the elves were good at everything, but Twinkle especially. The reason Twinkle was so good at everything was because, even though she was a child, she was actually three hundred and seventy-two years old.

‘Three hundred and seventy-two and a half, actually,’ she told me on the first day. ‘I know that might sound confusing, but what happens to elves is that we grow older and older, and then we stop growing old the moment we reach our perfect age, the age at which we truly know ourselves and will be happy for ever. Most elves generally don’t find out who they are – what makes them happy, what they want to do – until they are quite old.’

I knew this already. For instance, I knew Father Topo was ninety-nine before he stopped ageing. Father Christmas – who is not technically an elf but a drimwicked human – stopped ageing somewhere in his sixties, when he discovered his destiny. But some such as Twinkle find out when they are very young. So Twinkle was eleven and three hundred and seventy-two (and a half) all at the same time.

There were about twenty of us in Snowball Class. As well as Twinkle there was also a tiny but extremely enthusiastic elf called Shortcrust, who was the junior spickle-dance champion, and Snowflake, who was a bit annoying and always laughed at me whenever I made a mistake, which was quite often.

We had different teachers for different subjects but our form teacher was Mother Jingle. She always looked at me with kind eyes, but I couldn’t help thinking she thought I was a big waste of space.

It was she who told me, in my first week, that I wasn’t ready for sleighcraft lessons just yet.

I felt anger boil inside me. It was an anger I hadn’t really felt since the workhouse, and Mr Jeremiah Creeper. ‘But I’ve flown a sleigh before! I flew Father Christmas’s sleigh! The biggest sleigh there is!’

She shook her head. ‘I’m sorry, but when people arrive at this school, they have to wait six months before they are allowed to start flying sleighs. Those are Kip’s rules, I’m afraid.’

‘But most people who start at this school are five years old. I’m eleven.’

‘You have lived for eleven years as a human, which is different. Humans aren’t made for flying sleighs.’

And that was the end of it. I had to wait. And in the meantime I had to get on with all the other lessons.

There was maths, with Pi, which was really tricky. You see, elf mathematics is very different to human mathematics. In elf mathematics the best answer isn’t the right one, it’s the most interesting.

‘Amelia, what is two plus two?’ Pi would ask.

‘Four,’ I would say.

And the whole class would burst out laughing. Apart from Twinkle.

‘Twinkle, tell Amelia the answer.’

And Twinkle would sit up straight and say, ‘Snow.’

‘Yes,’ said Pi. ‘Two plus two is snow. Or you could have said feather duvet.’

And then Twinkle would look at me and apologise for being right, which made it worse.

The other subjects were equally tricky.

There was Writing, Singing (my voice wasn’t cheerful enough), Laughing Even When Times Are Tough (a very difficult lesson), Joke Making, Christmas Studies, Spickle Dancing (a disaster), Practical Drimwickery (even more of a disaster, obviously), Gingerbread, General Happiness and Geography.

Columbus – the geography teacher I had met along with Pi that day in the sweet shop – was a lovely elf, and I had high hopes for his lessons. They sounded quite ordinary and human, but of course they weren’t. Elf geography was as crazy as all the other subjects. The whole of the globe, south of Very Big Mountain, was simply called ‘the Human World’. It didn’t matter if it was Finland or Britain or America or China, it was absolutely all the same to elves, and they left it up to Father Christmas – and now Mother Christmas – to plan which route Father Christmas should travel every year.

Everything this side of the mountain, on the other hand, was studied in great detail. These were called the Magic Places. And they included the Elf Territory (which was made up of Elfhelm, and the Wooded Hills, which was more accurately pixie territory, but apparently pixies were terrible at geography and didn’t care very much about the names of things and so none of them objected). The other Magic Places were Troll Valley, the Ice Plains (where Tomtegubbs could often be found), the Hulderlands (home to the Hulder-folk) and the Land of Hills and Holes.

Days and weeks and months went by. Father Christmas came home late a lot of the time, because this was the busiest year for the workshop ever. Mary was also very busy, as she was in charge of Christmas route planning. She had also begun to take drimwickery classes, so she could unleash her magic, but she was finding it quite difficult. Anyway, they both became very preoccupied and I didn’t want to bother them with my problems, so I just whispered my complaints to Captain Soot, who always purred some comfort.

I’ve always been the kind of person who could look after herself. I’ve always had to, really. And, in fact, for most of the year I made the most of it. And a lot of the time I had fun. A lot of fun. Living in Elfhelm was still a lot better than being an orphan in London.

I often went to Twinkle’s house to play elf tennis, which is exactly like normal tennis but with an imaginary ball rather than a real one. This was one elf sport I was good at, and I wished we could have played it at school. Then I would go home and read or bounce on the trampoline or read while bouncing on the trampoline.

Even my lessons weren’t all bad. Twinkle was fun to sit next to and always told great jokes, and Shortcrust would often entertain us with his spickle dancing at playtime. And even on bad days I kept on saying to myself that things would be much better when the sleighcraft lessons happened. But six months went by. Then seven. Then eight. And soon it was December, and it seemed that I might never be allowed to take part in a sleighcraft lesson and would always have to stay by myself in an empty classroom, staring out of the window at the other pupils in my class flying past in sleighs.

It was getting quite close to Christmas when I first spoke to Mary and Father Christmas about it. It was the day I first heard mention of the Land of Hills and Holes.

‘Where is it?’ I asked Columbus.

‘Very far away. The furthest away it is possible to be, within the Magic Places. About a hundred miles east of Troll Valley.’

‘And who lives there?’

The whole class knew the answer, but instead of giggling at me like they normally did they all went very quiet.

‘Some rather dangerous creatures.’

‘What?’

‘Rabbits.’

It was then my turn to laugh. ‘Rabbits? Rabbits aren’t dangerous.’

Columbus nodded wisely. ‘I see. You are thinking about the kind of rabbits you find in the Human World. Little cute hoppy things with big ears. Hop, hop, hop! Father Christmas told me about them. But no, these rabbits are very different. These rabbits are bigger. They stand on their hind legs. And they are’ – he took a moment, swallowed – ‘deadly.’

‘Deadly?’ I couldn’t help but smile. It sounded so ridiculous.

‘He’s serious,’ whispered Twinkle.

‘Yes,’ said Columbus, whose eyebrows lowered in disapproval. ‘And it’s no laughing matter . . . Who can tell Amelia about the rabbits who live in the Land of Hills and Holes?’

Snowflake was first with her hand up.

‘Yes, Snowflake?’

‘Their ruler is the Easter Bunny.’

I stifled a giggle.

‘Correct,’ said Columbus. ‘Their ruler is the Easter Bunny. Everyone knows that. Well, everyone apart from Amelia. Now, anything else?’

Twinkle, inevitably, put up her hand. ‘They have a very big army. There are thousands of them. Tens of thousands. And hundreds of years ago they had battles with trolls and elves. There were the Troll Wars, which they won, and before that, when elves used to live throughout the whole of the Magic Lands, the Rabbit Army fought them and beat them, and took the Land of Hills and Holes for themselves.’

Columbus, as always, looked very pleased with Twinkle. ‘Exactly. In the very olden days, when the rabbits lived in warrens below the ground, the elves and rabbits lived quite peacefully together. But then one day, when the Easter Bunny took over the army, he had a different idea. He wanted everyone to know about rabbits. Yes, they still kept their warrens to sleep and work in, but they no longer wanted to be scared or to hide away. Especially in summer. They liked the light. They liked the warmth. They wanted to be running free. They wanted to go wherever. Which would have been fine, but they didn’t want anyone but rabbits around them either. They forced the elves out. Well, those elves who made it out alive – which wasn’t many of them.’

‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘how terrible.’

Columbus sighed. ‘Well, it was a very long time ago. And the rabbits keep themselves to themselves and so do we. So there is nothing to worry about.’

‘How can you be sure?’ I asked him.

‘Because he’s the teacher!’ said Twinkle. Everyone laughed as if I was stupid. Still, my head was full of questions and the questions had nowhere to go except out of my mouth.

‘Why is he called the Easter Bunny?’ I asked.

Columbus again pointed at Twinkle. ‘Twinkle, explain why the Easter Bunny is called the Easter Bunny.’

Twinkle took a very deep breath and sat up super-straight. ‘He is called the Easter Bunny because it was Easter when they came out of their burrows. Easter is when things get warmer and lighter, and it was also when the first and last battle between the elves and the rabbits happened.’

‘Oh, so what was the Easter Bunny called before?’

‘Seven-four-nine,’ said Columbus. ‘Rabbits tend to call themselves numbers rather than names. They are a very mathematical species.’

‘Right,’ I said, ‘I see.’ But I didn’t really. There were still questions inside my head. For instance: if the Easter Bunny and his Rabbit Army wanted to be everywhere, why didn’t they ever want to be in Elfhelm? Was the threat from the rabbits over? Was the Easter Bunny even still alive?

When I got home that evening I asked Father Christmas about the Easter Bunny.

‘Oh,’ he said, as we made paper chains, ‘the Rabbit War was way before I arrived here. Way before I was even born. There are some very, very old elves who remember what life was like in the Land of Hills and Holes. Father Topo is one of them. He was six at the time, when the elves had to retreat here. He said it wasn’t so special and most elves didn’t really miss it. It was a very flat place. No woods. No hills. Nothing except rabbit holes . . .’

An hour later, we were around the table, eating cherry pie.

I was still curious about rabbits. ‘If it’s so boring, how do we know the rabbits won’t come here and take Elfhelm too?’

Father Christmas smiled that reassuring smile of his. His eyes twinkled. ‘Because it was three hundred years ago. And in all that time there hasn’t been so much as a single bunny hop near Elfhelm. Whatever the rabbits are up to, they are up to it a long way away, and so there is no need to worry about anything at all. Nothing’s changed.’

That reassured me. But my face must have still looked glum, because Mary said, ‘What’s the matter, sweetheart?’

I sighed. I had always thought it best not to complain too much about life here, as there was no doubt that it was a lot better than life in Creeper’s Workhouse in London. But Mary’s stare was the kind of stare that made you have to tell the truth, so I came straight out with it.

‘School,’ I said. ‘School’s the matter.’

Mary’s head tilted in sympathy. ‘What’s wrong at school?’

‘Everything,’ I said. ‘All year it’s been a bit tricky. I’m just not good at elf subjects. They don’t make any sense to me. And I’ll never get the hang of elf mathematics . . .’

Father Christmas nodded. ‘Ah, yes. Elf mathematics does take some getting used to. I couldn’t believe it when I learned that the five times table here is an actual table – made of wood, with five legs. And long division is just normal division that you write down really slowly. But don’t worry. Everyone finds it hard.’

‘But they don’t,’ I said, picturing in my mind Twinkle’s hand shooting up faster than a star. ‘And it’s not just maths either. I find it all hard. I am the least cheerful singer the school has ever known, even when I really try. And Laughing Even When Times Are Tough is a really stupid subject to begin with. I mean, why should people laugh when times are tough? If times are tough, I think it is perfectly normal not to smile. You shouldn’t have to smile at everything, should you?’

‘Oh dear,’ said Father Christmas. ‘I daren’t ask about the spickle dancing.’

‘It’s terrible. Humans just aren’t made for spickle dancing.’

‘Tell me about it,’ said Mary.

‘I mean, I’m fine with the footwork but it’s the hovering in the air. That’s just impossible.’

Father Christmas winced as if a firework had just gone off. ‘Don’t say that word.’

I must have been in a very bad mood because all of a sudden I was saying it, over and over. ‘Impossible. Impossible. Impossible. Impossible.’

‘Amelia,’ said Mary, ‘you know there is no swearing in the house.’

‘But impossible shouldn’t even be a swear word. Some things simply are impossible. For an ordinary normal human being spickle dancing simply is impossible. And Practical Drimwickery is impossible. And on some Monday mornings even Happiness is impossible.’

‘Happiness is never impossible,’ said Father Christmas. ‘Nothing is impossible. An impossibility is just a—’

‘I know. I know. An impossibility is just a possibility you don’t understand yet. I have heard it a hundred times. But what about walking on the ceiling? That’s impossible. What about flying to the stars? That’s impossible.’

‘It isn’t, actually,’ muttered Father Christmas. ‘It isn’t impossible. It’s just not the right thing to do. And that’s a very big difference.’

‘Listen,’ said Mary. ‘I know how difficult it is, fitting in. I’ve been taking drimwickery classes for months and I’m getting nowhere, but I’m going to keep trying. There must be some subjects you enjoy?’

I thought. Captain Soot rubbed his head against my leg, as if to comfort me.

‘Yes, there is one. Writing. I like writing. I like it a lot. When I write, I feel free.’

‘Well, there you go. That’s good,’ said Father Christmas. ‘And what about sleigh riding. You like sleigh riding, surely? You are brilliant at sleigh riding.’

And then I told them what I had been too ashamed to tell them. ‘They don’t let me do that.’

‘What?’ asked Mary and Father Christmas both at once.

‘Because this is my first year at the school. And because I am a human. They said I had to wait six months until I could start flying sleighs. Nearly a year now has passed. But it’s okay. They might be right. Maybe Father Vodol was right, at your wedding. Maybe I don’t belong here.’

‘What a load of old butterscotch!’ said Mary, whose cheeks were even redder than usual. ‘You belong here as much as I do. Or as much as anyone, in fact. The likes of us, Amelia, were always made to feel like we were a burden. Send us off to the workhouse! Out of sight! But you are a good person, Amelia, and goodness belongs anywhere in this world. You remember that!’

‘Mary’s right,’ agreed Father Christmas. ‘And Father Vodol is a hateful elf who should be ignored. You have just as much right to fly a sleigh as any elf child has. Don’t worry! I’ll have a word with the school. And with Kip at the School of Sleighcraft. I’ll put an end to this silliness. But only on one condition . . .’

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘That you try not to say the word impossible in this house again.’

I laughed. Mary laughed. Even Captain Soot seemed to laugh. ‘All right. It’s a deal.’