Читать книгу Obama and Kenya - Matthew Carotenuto - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

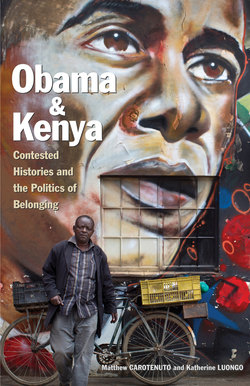

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Obama and Kenya in the Classroom

In 2008 we witnessed the global flood of attention directed toward Kenya as the world aimed to better know and understand the complex heritage of Barack Obama Jr.—the Hawaiian-born son of a white woman from the American Midwest and a black man from East Africa. The Obama and Kenya connection, an important theme in the explosion of biographies that accompanied the election of the first African American president of the United States, sparked a number of debates in classrooms around the globe. As a wide variety of authors of varying credentials and political stripes scrambled to write the story of the Obama family and attach it to American history, simplified and boldly inaccurate narratives about Kenya’s past and present began to proliferate. Obama and Kenya critically challenges and corrects these depictions, showing how Kenya’s past and present are relevant not only to African history, but to American and world histories. This book also provides a contemporary space for students of history and African studies to examine how both popular and scholarly narratives often refract analysis of the past through the lens of contemporary political discourse.

Kenyan history is certainly not something the average student or “history buff” encounters regularly on the shelves of the local bookstore or while flipping through documentaries on the History Channel. If one does stumble upon literature or media concerning Kenya, the stories these sources tell tend to range widely in tone, evidence, perspective, and bias. For instance, scholars note that up until Kenya’s tumultuous 2007–2008 election season, much of the journalistic writing on Kenya had typically characterized the country as “an island of peace and economic potential in a regional sea of stateless chaos (Somalia), genocide (Rwanda), mad dictators and child soldiers (Uganda), and a decades-long civil war (Sudan),”1 thereby contrasting Kenya with its more fractious and problematic neighbors. Other sorts of popular accounts drew heavily on colonial nostalgia, making Kenya out to be a romantic world of tented safari camps and sundowner cocktails. In both cases, the ever-present threat of “tribal” violence simmers below the surface of an otherwise idealized Kenya. As Obama and Kenya argues throughout, such prevailing stereotypes fit broadly with the way Africa is typically depicted in popular discussions about the continent’s histories, cultures, and politics. It shows how these stereotypical representations have driven debates about Obama’s connection to the continent and about Kenya’s place not simply in African history, but also in world history.

As American scholars teaching African history and world history courses in the United States, we regard challenging stereotypes and correcting misinformation about Africa as essential parts of our pedagogy and as central to equipping students with key skills in historical analysis. Most students come to our classes with little or no exposure to African history, and if they have learned about Africa in high school, it has been principally through the lens of African American history or via the history of European imperialism. While they might have learned a smattering of facts, for instance, that American slaves originally came from West and Central Africa in the 1600s or that Europeans “carved up the continent” at the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, students often complain that they have rarely, if ever, had the chance to examine African history from African perspectives or to learn about how African actors have engaged in global historical events and processes. Obama and Kenya provides a critical space in which to do both.

Introductory discussions in our classes about what we know about Africa and how we know it stimulate rich debates about not only the legacy of racism and ethnocentrism in American high school curriculums but also the stereotypes about Africa to which American students have frequently been exposed through film, literature, and popular media. These discussions are also useful in opening a dialogue about the politics of who writes the histories we encounter both inside and outside of the classroom and how African voices and experiences, if presented at all, are often framed as only marginally important in the context of world history.2 Obama and Kenya uses the story of an American president and his Kenyan roots to ask larger questions about historical representations of Africa and the ways both Africans and non-Africans have drawn on a US president’s personal and political biographies to tell very particular stories about the world’s second-largest continent. For teachers and students of African and world history, Obama and Kenya speaks to global discourse about Africa today and to key themes in the continent’s history over the last one hundred years. In doing so, it analyzes the political work these representations have done and continue to do in Kenya and abroad.

Focusing on contested narratives of British colonialism in Kenya and the challenges of building a national identity after independence in 1963, we explore how the Obama family is represented in relation to histories of Kenya’s colonial era and the early decades of independence, paying close attention to how Kenyan voices have debated this relationship in oral, written, and digital form. With Barack Obama Jr.’s political rise taking place firmly in the digital age, the story of Obama and Kenya provides a unique opportunity to analyze how Africans debate the past in a variety of forums and how access to political and social discourse has changed over time. Primary sources, ranging from social media to political cartoons to tourist advertisements, are now available at the click of a mouse and form a key part of a growing body of digitized archival material in African history.3 We have compiled a number of these digitally available primary sources on a companion website (obamakenya.org). Obama and Kenya and obamakenya.org highlight these useful resources so that readers can scrutinize primary sources themselves, hone their own skills in historical analysis, and further grasp how Kenya’s contested histories speak to broader issues in Africa and world history.

The history of Kenya over the last century offers an important case study in both African history and world history. Given its location in East Africa, Kenya’s history is often absent from the broader secondary school curriculum in the United States, which typically focuses on the historical geography of the Atlantic slave trade and its significance to African American history. However, Kenyan history from the precolonial era forward offers countless examples of transnational connections, which speak broadly to comparative studies of European imperialism and the global history of trade and cultural interaction in the Indian Ocean world. Kenya’s colonial experience, in which development occurred through massive land grants to a small coterie of white settlers who displaced Africans from their homes and turned them into squatters, resonates potently with the histories of other settler colonies from Zimbabwe to Algeria.

Among the movements for independence from colonial rule that swept the continent in the mid-twentieth century, Kenya’s anticolonial struggle is the key exemplar of African resistance through violent insurrection. The Mau Mau rebellion—as Kenya’s complex anticolonial contest is known—which motivated the British to throw the military might of their waning empire against the Kenyan rebels, the Land and Freedom Army, was also frequently invoked by participants in the burgeoning American civil rights movement.4 With the advent of independence in the 1960s, Kenya wrestled with the legacies of colonial rule while negotiating Cold War tensions and the challenges of local development. As in many African nations struggling to develop after decades of colonial neglect, Kenya’s economy failed to take off, thus driving a new wave of migration abroad in search of better opportunities for work and education. Kenyan migrants of this era included the father of a future US president.

Critically analyzing Kenya’s colonial experience and the challenges the new nation faced after independence offers students of African history and world history a great deal of thematic, topical, and factual information to bring to bear in an array of comparative contexts. While many popular narratives of Obama and Kenya recount a profoundly simplistic view of the country’s past and present, the contested histories and the politics of belonging in Kenya cannot be distilled into a simple, single story about the son of an African “goat herder.”5 Further, discussions of the diverse symbolism and meaning of the Obama presidency should not be confined to the American history classroom, as the connection between Obama and Kenya provides a powerful personalized account through which students can debate critical issues that have shaped Africa’s place in the world for much of the last one hundred years.

Obama and Kenya is divided into two parts that both serve to introduce readers to the Obama and Kenya connection more broadly and that provide more focused examples of the ways in which diverse audiences have woven Obama into particular African stories and themes. Part 1 begins by exploring the origins of Kenya’s fascination with Obama. The authors’ personal accounts of conducting research in Kenya during the 2004 US elections underscore the complexity of Kenya’s politics of ethnicity and how the roots and relevance of Obama’s connections to East Africa reveal a deeper window into representations of Kenyan history from colonial times to the present. Chapter 2 builds on this introduction and familiarizes the reader with key themes that have dominated the last one hundred years of Kenyan history: colonialism, ethnicity, regionalism, migration, and electoral politics. We introduce the unfamiliar reader to the fractious worlds of colonial and postcolonial Kenya where the politics of belonging—of race, class, ethnicity, or other forms of social identity—often work to shape historical realities. In doing so, we briefly explore the dominant myths about the country and contrast them with the realities of Kenyans’ lived experiences. Here the goal is not just to narrate a series of past events, but rather to draw close attention to how myths and realities operate in constant tension with each other in reconstructions of Kenya’s contentious histories.

Chapter 3 situates Obama in the regional history of the Luo community to reveal how a US political figure has fit into local Kenyan understandings of the nation’s diverse social and cultural landscape. Obama’s unlikely rise to the top of the political order in the United States was regarded by many Kenyans specifically as the ascendancy of a Luo, rather than more generally as that of an American of Kenyan or African descent, and revived specific debates about the failures of a number of Luo politicians to achieve similar feats in East Africa. Here Obama and Kenya returns to the question of the saliency of ethnicity in Kenya’s political history and examines how the framework of contemporary ethnic identities, assembled by specific historical actors beginning in the colonial era, has impeded the development of an inclusive Kenyan national identity after independence.

Part 2 of Obama and Kenya shows how the past and the present are intimately connected in the ways local Kenyan and international audiences have debated the Obama and Kenya connection since 2004. Chapters 4 and 5 take the story of Obama and Kenya to the United States and then back to Kenya to show how Obama’s political opponents in the US and his supporters in Kenya have made sense of the US president’s Kenya connection by reinvigorating stereotypes and creating new, yet highly erroneous, narratives of Kenya. In doing so, we address the important issues of when and how to “trust” primary and secondary historical sources. Offering a nuanced look at the myth and reality of popular writings about Kenya, Obama and Kenya examines what happens to Kenya’s image abroad when the country’s history is used as a political commodity, and what happens to the politics of rural development at home when tourists imagine the Obama family’s homestead in Western Kenya as a global historical monument.

In chapter 6, we return to the question of the political utility of historical representation using the lens of twenty-first-century electoral politics. This chapter examines global representations of Kenya’s hotly contested December 2007 presidential election and its violent aftermath, which drew upon well-worn, ahistorical clichés about ancient tribal rivalries. The text then turns to the presidential elections of March 2013, which again revived the familiar portrayal of Kenya as a nation filled with “tribal gangs” roaming the forests and ready to unleash the savage violence of the past. The chapter also addresses how the election pitted Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Kenya’s first president, and Raila Odinga, son of Kenya’s first vice president, against each other in a contest many Kenyans viewed as part of a historic struggle of regional and dynastic family politics. As the political discourse clearly showed, the legacy of colonialism was a regular point of reference in this high-stakes political contest, where particular narratives of the past were often evoked on the campaign trail and even among pundits abroad. Picking up where chapter 6 leaves off and focusing on the Obama administration’s reactions to the 2013 elections, chapter 7 explores the ways in which the administration has or has not engaged with Africa since 2008. Returning briefly to the continent-wide celebrations of Obama’s victory in 2008, the chapter asks how African expectations for the Obama presidency have aligned with American policy and practice. The epilogue focuses on Obama’s official state visit to Kenya in July 2015, analyzing both how the first such visit by a sitting US president was figured in the two countries and the issues that Obama, as the first Kenyan American president, was uniquely positioned to address.