Читать книгу Obama and Kenya - Matthew Carotenuto - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Discovering Obama in Kenya

The seeds for this book were sown in the multitude of places we visited and the variety of voices we encountered as eager graduate students fumbling through our dissertation fieldwork across Kenya’s diverse landscape in 2004. As we read through stacks of dusty files at the Kenya National Archives (KNA), conducted interviews along the rocky shores of Lake Victoria, and engaged in more casual debates in the bustling cafés and nightclubs of Nairobi, Kenya’s energetic, cosmopolitan capital city, we never imagined that ten years later our multifaceted research experiences would lead us to write a book about the place of an American president in the history of Kenya.

While in the last decade we have engaged in countless conversations about and collected many examples of the local and global significance of Barack Obama’s ties to Kenya, one episode at an American embassy event in Nairobi pointed to a need for and shaped the vision of our book. Fortunate to be supported by Fulbright fellowships through the US Department of Education, we received formal invitations in the fall of 2004 to attend an exclusive celebration that takes place in the early morning hours only once every four years during the first week of November—an Election Day breakfast held by the American embassy in Nairobi. Flattered to be invited to a special gathering at the posh Nairobi residence of the then US ambassador to Kenya, William Bellamy,1 excited about whom we might meet, and like all graduate students pleased by the prospect of a free meal, we luckily landed at what must have been the very bottom of an exclusive invite list that included much of Kenya’s political elite.

On the morning of November 3, with Kenya some eight hours ahead of eastern standard time, much of the diplomatic and expatriate American community in Kenya had been up all night, tracking the election returns in the US presidential race. Having followed the campaign all fall as we completed our research projects on colonial and postcolonial Kenyan history, we, too, had stayed up, bleary-eyed and eager for the results. Focused mainly on the presidential race between Republican incumbent George W. Bush and his Democratic challenger, John Kerry, we had paid little attention to a more minor contest in the midwestern state of Illinois that had already begun to overshadow the presidential race for many Kenyan audiences.

Unaware of the singular moment that would unfold that morning, we left the congested confines of Nairobi’s central business district during the predawn hours to make our way to the ambassador’s residence in the leafy suburb of Muthaiga. Heading out of the city center during the ritual tussle of Nairobi’s hectic morning commute, we escaped the brunt of the daily bumper-to-bumper line of packed buses, overflowing matatu (van taxis), and commercial traffic that Kenyans simply refer to as “the jam.” Turning off the main highway not too far from downtown, we entered a tranquil suburban relic of the colonial past. Now a mixed bastion home to international aid workers, diplomatic personnel, and Kenya’s political elite, the tony neighborhood of Muthaiga has roots dating back to the early twentieth century, complete with the golf outings and colonial cocktail parties that made up the days of Britain’s privileged white settler class.2 Like many of the homes and businesses, the US ambassadorial residence still reflects the imposing architecture and manicured style of the British colonial past and is hardly visible behind the razor wire–topped walls and guarded gates that dot one of Nairobi’s most exclusive neighborhoods.

Arriving just before six in the morning, we waited in the long security line along with an array of impeccably dressed guests to be welcomed to the traditional American election party, already off to a lively start despite the hour and the fact that US media outlets more than seven thousand miles away had yet to finalize the tally of votes cast the day before. Clearing the armed security and entering the residence, we were struck by the chatter expressing the broad Kenyan interest in the US elections as well as the lavish spread of food and the numerous satellite televisions scattered across the living room, veranda, and pristine gardens of the residence compound that displayed real-time CNN election results.

Mixing in this unfamiliar world, we tentatively scanned the slew of guests and noticed faces familiar to us from the pages of the Kenyan press, including influential members of the international diplomatic corps and a sampling of Kenya’s political elites. Spotting figures ranging from then official government spokesperson Alfred Mutua to then minister for the environment Kalonzo Musyoka, we spent the next few hours sipping tea and trying to make awkward small talk with a sea of parliamentarians, permanent secretaries, and other government officials who operate high above the daily lives of the everyday Kenyans, the wananchi as they are known in Kiswahili, and certainly outside the sphere of the average US graduate student.

In our awe of the overall gathering that day, one group of Kenyan politicians stood out from the rest and instantly captured our attention. Entering amid an entourage of supporters, the Luo leader Raila Odinga was clearly a visible star among this elite group of “Big Men.” Hailing from Siaya, the Western Kenyan county that was also the birthplace of Barack Obama Sr., Odinga has been a fixture in Kenyan politics at the national level since the 1980s. Son of Kenya’s first vice president, Oginga Odinga, and scion of one of Kenya’s most prominent political dynasties, by 2004 Raila, as he is popularly called, was known in local circles as the edgy political dissident and exile from the 1980s who had risen to represent Nairobi’s Langata Constituency in Parliament in the 1990s and was easily the most recognizable politician from Kenya’s relatively small but politically important Luo community. That day, however, Raila was not flying the metaphorical flag of Kenya’s political opposition, but he was instead sporting a wide American flag tie set off by a large Obama pin stuck prominently to the lapel of his pricey suit. His entourage was similarly, though less flamboyantly, kitted out in visible support for the United States broadly and Obama particularly.

While it was not unusual for guests to demonstrate their support for the American electoral process during a gathering at the US ambassador’s home, we were immediately struck by how Raila exhibited fervent enthusiasm for a relatively unknown senatorial candidate from Illinois, Barack Obama. In the months leading up to the November election, Matt Carotenuto had fielded an increasing number of questions from Kenyans about this “Obama fellow” during his fieldwork near Raila’s home areas in Western Kenya. Word had gotten around that the Democratic candidate campaigning to represent Illinois in the US Senate was in fact the son of the same Barack Obama Sr. who was born in the 1930s not far from Raila’s hometown close to Lake Victoria in the Western Kenyan county of Siaya. Some nine years older than Raila, Obama Sr., a onetime government employee and midlevel technocrat, had died tragically in an automobile accident in Nairobi in 1982.3 Though successful in his own right, Obama Sr. was certainly not of the same political pedigree or elevated achievement as Raila, yet, in Western Kenya, a strange sense of dynasty had nonetheless begun to emerge around Barack Obama Jr., the US senatorial candidate whose ties to Kenya generally and to the history of the Luo community particularly had been seized upon by Luo people in the months leading up to the American elections. However, it was not until the lopsided victory of Obama Jr. over his Republican challenger in Illinois was declared that we began to witness the significance of this US electoral victory to international relations and to “Big Man” politics in Kenya.

Called long before the presidential race, the senatorial victory of Barack Obama Jr. drew the most dramatic response from the Kenyan guests of any election results announced that morning. A sporting cheer and rounds of overwhelming applause led by Raila’s group erupted when CNN declared Obama the winner.4 However, instead of simply joining politely in the applause celebrating the election of a junior senator with paternal ties to Kenya, Ambassador Bellamy made his way straight for the Odinga contingent and began shaking Raila’s hand boisterously as if the Kenyan politician’s own brother had been elected. In congratulating Raila, first among the cream of the Kenyan political elite present at the party, and doing so in such a public space, Ambassador Bellamy, who drew some subtle stares from various other Kenyans at the gathering, seemed to imply that Obama’s victory was not something to be celebrated by the wananchi across Kenya but something belonging more narrowly to a particular region and ethnicity; a particular victory for Western Kenya and for the Luo.

Congratulating Raila first was a bold diplomatic move to make that morning during an event billed as nonpartisan—both American and Kenyan political temperatures were running high in 2004—and inspired a number of important initial questions about the significance of the Obama-Kenya connection in both local and global political circles. Was Bellamy’s hearty handshake in response to a Democratic victory merely a nod to the Democratic leanings of the party guests? The traditional, friendly straw poll conducted by the embassy that morning had revealed that attendees overwhelmingly favored Democratic nominee John Kerry’s candidacy for president. Or was the ambassador perhaps simply trying to cultivate a personal relationship with one of Kenya’s most important political figures regardless of how alienating this may have been to those in the audience who resided at the opposite end of the political spectrum from Raila?

These questions carry weight in large part because in the interpenetrated worlds of international affairs and global commerce, Kenya is an important strategic ally and trading partner of the United States and of many other Western nations. The country borders the “hot zones” of the Horn of Africa and northern Uganda and South Sudan, while its principal port at Mombasa serves as the economic gateway to many of the markets of Eastern Africa, spanning Uganda and Rwanda to Ethiopia and South Sudan. After the US embassy in Nairobi was bombed by Al-Qaeda in 1998, killing 213 Kenyans and American diplomatic staff, Kenya became one of the American government’s chief allies in the growing “war on terrorism.” The United States expanded its embassy, already the largest American embassy in Africa and the second-largest American embassy in the world, into a huge fortresslike compound not far from the ambassador’s residence.5 Nonetheless, even taking into consideration the importance of the US diplomatic relationship with Kenya, the ambassador’s acknowledgment of Raila’s “special relationship” with Obama spoke to more than US-Kenya ties forged over terrorism and trade. Rather, as social historians of twentieth-century Kenya, we recognized that Bellamy’s gesture, and the awkward smiles of the other Kenyan guests that followed it, was a testament to the widely acknowledged and broadly accepted purchase of ethnic politics and regionalism in contemporary Kenya, formations with deep roots in the colonial past.

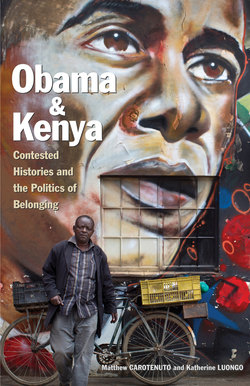

Over the coming weeks and months, we watched closely as a steady stream of politicized popular discourse, occurring informally in Kenyan homes and workplaces and on the pages of the local press, about the connection between Obama and Kenya generally, and Obama and the Luo particularly, began to flow. Indeed, over the weeks and months that followed his election, Senator Barack Obama was publicly celebrated as a “son of the soil” of Kenya in public discourse, but in other debates at home and abroad, his Kenyan roots were firmly being replanted in Kenya’s western regions, casting him first and foremost as a member of the minority Luo community, who make up just over 10 percent of the population.6 “Obamamania,” as Kenyans came to refer to the celebration of Obama’s rise, began to grip the nation in late 2004. T-shirts and commemorative songs written about the junior senator from Illinois began to be seen and heard on the streets of Nairobi and in the Western Kenyan city of Kisumu even before Obama gained widespread national appeal in the United States.7

Obamamania reached a fever pitch four years later with the next round of American presidential elections in 2008. Importantly, what we came to glean over several years of research sparked by the ambassador’s enthusiastic congratulations offered to Raila was how the story of Barack Obama Jr. and his Kenyan heritage has been used by numerous political actors in Kenya and abroad to frame narratives of Kenya’s history that have both perpetuated common Western stereotypes about Africa and helped to reinforce the contentious politics of ethnicity rooted in Kenya’s colonial history. These narratives of Kenya’s past engendered by the Obama-Kenya connection have held world historical significance, contributing to the shape of contemporary electoral politics both in the United States and in Kenya. For political actors in both Africa and the United States, the Kenyan roots of an American president (read and complicated through the lens of identity politics in two very different contexts) have offered ample resources with which to envisage their own localized concerns and to market narratives of Africa’s past to distinct audiences. Further, viewed through the prisms of race and ethnicity and refracted through politicized understandings of Kenya’s past, the story of Obama and Kenya has been interpreted not simply as an American political story but as an event of national political import in Kenya and a historical moment of global significance. For political actors and audiences in Kenya, the United States, and an array of places and spaces around the world, the targeted telling of the Obama and Kenya story has transformed the Kenyan past into a sort of political currency, a situation that, as Dane Kennedy argues, “highlights the polemical power of history and the complex array of politically and morally freighted meanings that inform its practice.”8

As historians of Kenya, we trace the impact and meaning of these interwoven histories of Kenya and the Obama family after more than a decade of historical and political entrepreneurship aiming to capitalize on the Obama-Kenya connection. Depictions of this connection, found in productions as diverse as best-selling political biographies and amateur histories, have influenced the ways in which multiple publics around the world conceive Kenya’s past and present, and also point to the increasingly digital methods and means through which local and global histories are both produced and consumed. Indeed, Obama’s political ascendancy created a unique space in which African history was debated in real time by global audiences who read, wrote, blogged, chatted, and tweeted about the significance of the Obama family’s place in the history of Kenya, and the place of Africa in world history more generally.

Throughout this book we identify and break down the dominant narratives about Kenya’s colonial past and postcolonial present in order to dispel some of the stereotypes of and misunderstandings about Kenya’s history that the Obama story has rekindled and fanned. Using a variety of sources, from archival records and oral interviews to the popular press and amateur histories, we analyze how Obama’s Kenyan roots, and the histories associated with them, have been interpreted by and for a range of local and international audiences. From Obama’s political supporters in East Africa to his opponents abroad, examining the ways in which local and global audiences have interpreted Obama’s connection to Kenya can tell us not only about how Kenya’s past and present (and Africa and its place in the world more generally) have been represented since the early twentieth century, but also about the social, political, and material significance of these representations.

Placing Obama and His Kin in the Contested Story of Kenya

Constructing a history of Kenya through the story of an American president’s paternal heritage is certainly not an easy task, and it is one we take on with great caution and with the goals of clarification and correction. Kenya is a large country, bigger than France and nearly the size of Texas.9 Spanning the equator, its landscape represents many points across the environmental spectrum. A thin, tropical band runs along the Indian Ocean, while vast savanna grasslands with variable and often unreliable rainfall patterns dominate more than 70 percent of the country’s interior. Much of the northern region of Kenya, extending to the borders with Somalia, Ethiopia, and South Sudan, consists of sparsely populated terrain suitable mainly for pastoralism due to the semiarid climate and history of underdevelopment in the area. In fact, when traveling from the capital city to northern towns like Garissa, Wajir, Marsabit, or Lodwar, one is often greeted with the wry question “How is Kenya?”—a query reflecting both the sharp physical divide between the dry, sparsely peopled North and the more fertile, more densely populated regions of the country, and the historical divide in development created by policies dating back to the colonial era that have favored the rest of the country to the expense of the North.10

Over much of the last century, the southern-central and western regions of Kenya have been most intensely marked by colonialism and its legacies and have dominated colonial and postcolonial politics. From Mombasa to Kisumu, the stories of the Obama family and Kenya span these regions, revealing the broader history of Kenya’s colonial past and illustrating the postcolonial political and socioeconomic challenges that have shaped Kenya since it gained independence from Britain in 1963. Rising to an average of more than five thousand feet in many places, the temperate and densely populated regions of Central Kenya form the economic engine of the country’s largely agriculturally based economy, in which tea, coffee, sugarcane, and other cash crops are grown alongside subsistence staples like maize and wheat throughout rural areas. Cutting a swath through the center of the country is the Great Rift Valley, flanked by magnificent escarpments, volcanic massifs, and the snowcapped highest peaks of Africa, Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro. To the west, the country is bounded by the craggy beaches of Lake Victoria, the source of the Nile River and the historical home of Kenya’s Luo-speaking populations and of Obama’s kin and ancestors.11

Figure 1.1. Famed Kenyan critique of Obamamania from renowned East African cartoonist GADO (Godfrey Mwampembwa). Daily Nation, June 10, 2008.

While the flora and fauna of Kenya’s countryside have long fascinated visitors, the demographic history of Kenya reflects dramatic changes similar to those of neighboring countries in regard to migration patterns and to the related economic prospects of the wananchi. With a population of just over eight million in 1960, by 2013 Kenya had swelled to more than forty million citizens, a quarter of whom now reside in urban environments.12 In fact, the Kenyan government projects that by 2030 its population will exceed sixty million, with more than half of the wananchi making the move from the countryside to the city.13 Even the casual visitor to Nairobi cannot miss the effects of this change as a construction boom involving large-scale infrastructure projects dominates both the high-rise cityscape of downtown Nairobi and the sprawling suburbs of the greater capital’s three million–plus residents.

Just as the map of Kenya reflects a great deal of environmental and demographic variability, its cultural landscape is equally diverse. With a fast-growing population speaking more than forty different languages, no one linguistic or cultural group represents a majority of the population.14 Like most African countries, Kenya’s history as a nation-state does not start with the founding of an ancient African kingdom or empire, but instead begins with the story of how late nineteenth-century British imperialism and African resistance to it carved out the borders of the Kenya Colony from among people whose cultures, connections, and histories extended far beyond colonial boundaries. Even a casual observer cannot help but notice evidence of Kenya’s long-standing global connections residing side by side with the vestiges of colonial rule from the saltwater shores of the Indian Ocean to the freshwater beaches of Lake Victoria.

For example, visiting Mombasa, Kenya’s second-largest city and an urban center of note for more than a millennium, one is struck by the muezzin’s call to prayer, so familiar in the predominantly Muslim, Kiswahili-speaking areas of Kenya’s coast, echoing over the fortified walls of Fort Jesus, erected by the Portuguese in the late 1400s, and across a port where international cargo vessels and dhows, a type of lateen-sail vessel used in the region for a thousand years, both ply the waters. Unsurprisingly given the region’s deep cosmopolitan connections, inhabitants of the Kenyan coast, both past and present, have imagined their distinct “Swahili” religio-cultural identity as intimately linked with the experiences of other Indian Ocean communities from the Middle East to Indonesia.15 Yet, the Swahili Coast is not the only region of Kenya where identity has been imagined through webs of cultural and linguistic connections constituted by long-standing patterns of migration and trade.

Heading west to the freshwater coast of Lake Victoria, where Kenya borders Tanzania and Uganda, one arrives in the port city of Kisumu. In the home of Kenya’s Luo community, the paternal kin of Barack Obama, one encounters traders from around the Lake Victoria basin mingling on the beaches, wolfing down grilled tilapia and ugali, a thick maize meal porridge, at long picnic tables while chatting in a mixed lingua franca of English, Kiswahili, and Luo as Swahili hip-hop from Tanzania competes with Congolese Lingala and local Benga and Ohangla beats. In this region, too, connectivity and a sense of distinct linguistic-cultural identity stretch deep beyond present-day commerce, back centuries to the migrations of people from along the Nile up to northern Uganda and down to South Sudan who belonged to groups related in language and practice to Kenya’s Luo community. Here in Barack Obama’s ancestral home, colloquially called “Luoland,” many Luo signal as much affinity for other Nilotic-speaking groups as they do for their fellow Kenyans nationwide.16

In sum, the vignettes presented above point to the book’s key themes—the complex narratives that make up Kenya’s history and how the politics of belonging create sometimes competing notions between national and local identities. As Obama and Kenya shows, there is no one story of what it means to be Kenyan. Rather, identities are historical, flexible, multilayered, and crosscutting. As such, any claim to the existence of a definitive “Kenyan” identity or to a singular Kenyan history is fraught with inaccuracy and bias. Here we also want to caution readers about the politics of language broadly used in the debate about Obama and Kenya and direct them to pay close attention to the politics of one loaded term, “tribe,” which can have disparaging connotations, but is also widely employed by Africans themselves. In Western discourse, “tribe,” “tribal,” and “tribalism” have often been used to dismiss Africans as primitive, primordial. Such usage does not reflect how African communities figure their own identities along tribal lines.

As much as this book is about unpacking the contested histories that Obama’s East African roots underscore, it is also an exploration into the local politics of belonging in Kenya. Many popular outside accounts frame the complex history of ethnic identity in Kenya with simplistic and static terms like “tribe” and use pejorative adjectives like tribal and tribalism to describe everything from cultural beliefs to political conflict. Like many students in our classes, we, too, agree that these words carry political weight in contemporary discourse that perpetuates understandings of African identities as “uncivilized,” “primitive,” and “timeless.” As the term “tribe” fails to capture the ways Kenyans have historically debated ethnicity as constantly changing, contingent, and negotiated, we reject the term in our own analysis and treat the Obama and Kenya connection as much more complicated than a simple story about the son of a “Luo tribesman” from Kenya hewing to his “tribal” heritage.17

Given Kenya’s fascinating environmental and cultural diversity, it is not surprising that the country and its people have inspired the production of numerous historical narratives. However, these works often deliberately fail to embrace Kenya’s complexity, instead simplifying or skewing Kenya’s multifaceted past to fit with particular social and political agendas. Since the earliest days of British imperial expansion in the late nineteenth century, Western audiences have been bombarded by scenes of majestic wild landscapes where heroic beasts are pitted against noble yet “savage” Africans. Further, literary and cinematic representations of a glamorous colonial life of sundowner cocktails and lion hunts abound, and films like the Oscar-winning Out of Africa have long helped to perpetuate romanticized images of the colonial period with the civilizing zeal of the “white man’s burden” lurking as a dangerous subtext.

While contemporary representations are perhaps more subtle than the popular accounts of the colonial era, Kenya’s past has long been narrated as the history of a wild environment brought into the “developed” world through colonial expansion targeted to serve European interests. For instance, when Frederick Lugard, a famous British colonial official and architect of imperial policy across much of the continent, wrote about The Rise of Our East African Empire, he cited the Earl of Rosebery’s now famous speech, delivered at the Royal Colonial Institute in 1893, which argued that the British were “engaged in ‘pegging out claims for the future.’ . . . We have to consider what countries must be developed either by ourselves or some other nation and we have to remember that it is part of our responsibility and heritage to take care that the world, as far as it can be moulded by us, shall receive the Anglo-Saxon and not another character.”18

Written in an era of colonial expansion and violent repression of African resistance across the continent, Lugard’s book argued that colonial policy in East Africa should keep with the nineteenth-century paternal logic of social Darwinism and scientific racism wherein African subjects would be expected to adopt the “three C’s”: Christianity, civilization, and commerce. Lugard argued:

The essential point in dealing with Africans is to establish a respect for the European. Upon this—the prestige of the white man—depends his influence, often his very existence, in Africa. If he shows by his surroundings, by his assumption of superiority, that he is far above the native, he will be respected, and his influence will be proportionate to the superiority he assumes and bears out by his higher accomplishments and mode of life. In my opinion—at any rate with reference to Africa—it is the greatest possible mistake to suppose that a European can acquire a greater influence by adopting the mode of life of the natives. In effect, it is to lower himself to their plane, instead of elevating them to his. The sacrifice involved is wholly unappreciated, and the motive would be held by the savage to be poverty and lack of social status in his own country. The whole influence of the European in Africa is gained by this assertion of a superiority which commands the respect and excites the emulation of the savage.19

Throughout the colonial period, this racist and ethnocentric view of Euro-African relations dominated how the story of Kenya was told, and historians have noted how these early, popular narratives have clouded the more complex story of Kenya’s colonial past and postcolonial present. For instance, David Anderson, in his seminal work on the anticolonial Mau Mau rebellion of the 1950s that ultimately led to Kenya’s independence in the early 1960s, notes that the rhetoric of popular, colonial accounts of the Mau Mau period differed little from the racist language of nineteenth-century writers like Lugard. Citing a 1955 best-selling novel about the well-known Mau Mau rebellion, Anderson highlights American author Robert Ruark’s warning to readers: “To understand Africa you must understand the basic impulsive savagery that is greater than anything we civilized people have encountered in two centuries.”20

Remaining largely unchallenged and even promoted by popular accounts produced throughout the colonial period, such stereotypical representations, as many African authors and scholars have long complained, have continued to be firmly perpetuated in print and on film long after the end of colonial rule. Painting Africans as marginal players in world historical events, these enduring stereotypes have long shaped the way many outside audiences have been introduced to and encouraged to think about Africa’s past. For instance, Kenyan author Binyavanga Wainana quipped in his 2005 satirical instructional essay, “How to Write about Africa,” that to sell books in the contemporary global market, authors needed to treat the continent “as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving. Or it is hot and steamy with very short people who eat primates. Don’t get bogged down with precise descriptions.”21

Boiling down complex historical events like Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion into simplistic accounts of savage violence or racial conflict is part of what Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie argues is the “Danger of a Single Story” of Africa.22 While such stories are most typically found in popular literature, Africanist scholars have had to combat similar Eurocentric and stereotypical readings of the past—sometimes even coming from the academy—since professional, scholarly study of Africa took off in the 1960s. For example, scholars have challenged the views of world-renowned Oxford historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who argued throughout much of the 1960s that the only issues worth exploring on the African continent were those that pertained to “the history of Europe in Africa,” dismissing the rest as “the unedifying gyrations of barbarous tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe.”23

Such blatant stereotyping and biased accounts cannot be ignored when analyzing how the political rise of Barack Obama has been depicted and the broader ways a global audience has interpreted his connections to Kenya. For many of his political opponents in the United States, Obama’s Kenyan heritage has provided key fodder with which to attack his political legitimacy through marketing stereotypical readings of African history and politics, renewed with the aim of linking Obama’s American political identity to erroneous accounts of “tribal” violence and anticolonial insurrection. However misplaced these analyses may be, they nonetheless have been crystallized in best-selling books and through documentary films since 2004 that have shaped global interpretations of both presidential elections in the US and contemporary Kenyan politics and history.24

An attention to the political uses of history also returns us to the congratulatory scenes we witnessed at the US ambassador’s residence in 2004. Here African political actors like Raila Odinga were actively trying to claim Obama as their own and market personal ties to his paternal heritage for their own political gain. In keeping with a long past of local patriotic history writing that often distills complex genealogies and local histories into simple narratives for political gain, Raila and others performed their historical commemoration that day with the celebrations of Obama’s Kenyan and Luo heritage. Shortly after, similar representations began to appear on the shelves of Nairobi’s bookstores and on the pages of Kenya’s popular press.

Scholars argue that such narratives of Kenyan history belong to a deep genealogy of regional ethnography and hagiography by way of which African “entrepreneurs [have] sifted through history and summoned political communities into being” by focusing on heroic and often uncritical narratives of the past.25 For instance, combing the publications and memoirs of Africans from the colonial period, one can often find histories of linguistic communities framed as mythical celebrations of romanticized traditions from a static and unchanging precolonial past. These texts were often authored by African colonial elites who sometimes elevated the role of important men, demonized all Europeans, and failed to critically examine the internal conflicts over gender, class, and generation that long predated the arrival of British colonial rule in the region.26

Thus, in endeavoring to claim Obama as their own, Raila and the Luo politicians by his side in 2004 treated the moment of the election party as an opportunity to display a certain version of the Kenyan past so as to promote the political significance of the Luo community and to demonstrate how the importance of this local ethnic identity—“Luoness”—transcended the boundaries of Kenya. It was of no concern to Raila or others that Obama himself did not identify as Kenyan or Luo, because they read his background through a distinctly Kenyan lens and not through the matrix of the mixed African American heritage that Barack Obama had spoken of so widely in his career as a US politician.27 Raila and his supporters were simply drawing upon strategies long used by African actors across the continent to reshape and market ethnic or regional identities for a variety of social, economic, and political reasons. These actions have consistently challenged notions that African ethnicities are static “tribal” identities rooted in the distant past. Indeed, scholars and Africans alike now regard ethnicity in Africa as a much more fluid category, one that can even act like corporate identity with a brand/image that is carefully managed, reimagined, and constantly marketed by both elite and local actors.28 For his part, Ambassador Bellamy may have also fallen into a trap of promoting a different stereotypical version of Kenya’s politics of belonging. By congratulating Raila, he was publicly confirming the victory for the Luo community and displaying an interpretation of Kenyan politics in a way that many Western journalists and other commentators might simply and uncritically dismiss as “tribalism” by another name.

Obama and Contemporary Kenyan Histories

Obama and Kenya is very much a Kenyan story, where the actual actions, feelings, and statements of the American president, while not insignificant, play only a minor role in structuring the debate about ethnic identity and the complex politics of belonging. Obama’s political ascendancy in the United States has stirred up various controversies about Kenya’s past from the colonial era to the present day, and provides a critical space in which to examine how representations of African history have been constructed and politicized throughout much of the twentieth century and how these representations have done important “work.” In popular sources about the president and in the explosion of Obama biographies, Kenya’s past and politics are sometimes treated as peripheral or are typically very much distorted to fit within the publication’s political bent. Few scholars have yet to take up the intertwined discourses about Obama, Kenya, and history, and until now no book-length study—scholarly or otherwise—has examined how Obama’s ascendancy to the “highest office in the land” has shaped the telling of Kenyan or African histories in a global context.29

Unlike those Africans living in the era of the late nineteenth-century colonial administrator Sir Frederick Lugard, Africans in the twenty-first century have channels at their disposal to fight back against politicized readings of their own histories and to generate real-time input to the contemporary twenty-four-hour media cycle of political commentary and historical debate. Thus, as much as Obama and Kenya is grounded in traditional sources—archival documents, oral interviews, and material culture—the book aims to examine the ways in which historians of contemporary Africa can add digital resources and other nontraditional source material to their analytical tool kits.30 While the United States Library of Congress has begun archiving blogs and tweets, and our own students debate complex issues with friends daily through social media forums and in other digital venues, we privilege the increasing number of African voices in the digital world who participate in debates about the Obama and Kenya connection in real time.31 We also pay close attention to how African voices in the digital age are consumed abroad, as global debates about Obama since 2004 have cited African news media and even transcripts of debates on the floors of Kenya’s Parliament now freely available online. In evaluating these new sources, it is important to ask how the digitized data we consume are produced and if the phenomenon is promoting greater equality in global discourse or simply providing new media to perpetuate long-standing inequality.

To fully understand the Obama and Kenya connection, we must take a broad historical look at Kenyan history and its representation in a variety of media. This history predates the 2004 election and even the 1961 Hawaiian birth of Barack Obama Jr. It begins in the colonial past and weaves its way through the story of Luo migrations from the colonial period and histories of how members of the Obama family and other Kenyans experienced the challenges of life under British colonial rule. The story also extends into the turbulent period of decolonization and independence and examines how different political actors have narrated this contested period to corrupt and claim ownership over Kenya’s struggle for independence and the postcolonial challenges of nationhood.