Читать книгу Hoggy: Welcome to My World - Matthew Hoggard - Страница 10

2 Gardens, Gags and Games

ОглавлениеIn case anyone is wondering, I never did quite make it as a vet. All those ball games I was playing rather got in the way and I ended up doing that for a living instead.

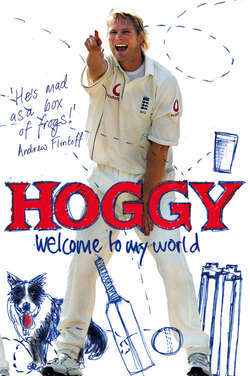

So if you’re a dog-lover who saw the front of this book and thought it was for you, well, the dogs will be featuring from time to time, but I’m afraid there will be a bit of cricket along the way as well.

If you really don’t like cricket, you can always look up Billy and Molly in the index and skip to those bits. And there’s always the photos for you to have a good laugh at. Everyone likes looking at those.

Anyway, sorry if you don’t feel you’ve had your money’s worth.

It’s mainly my dad’s fault, I think, that I became quite so keen on cricket. He hadn’t played much himself—the odd staff match here and there—but there was hardly a sport that he wasn’t interested in. And there really was no end to those games we played together for years when I was a lad.

Wherever we went, we would take a ball with us and Dad would think up some game or other and invent a set of rules to turn it into a contest. When we were up at the top field by the rugby posts, throwing a tennis ball or kicking a rugby ball at the crossbar, Dad would devise a points system of some sort to turn it into a proper game. We got one point for hitting a post below the crossbar, two for hitting a post above the crossbar and a jackpot of five points for hitting the crossbar itself.

I remember the first time I was given a hard ball. My nan and grandad had bought it for me from a flea market for 20p and I spent ages bowling with it in the back garden. I was desperate to have a bat against it as well, so Dad took me up to Crawshaw playing fields, where they had a concrete wicket covered with green rubber matting, which made the surface quite bouncy.

I was really excited about going up there and I ran up the dirt path that led up the side of the field. I couldn’t wait to play on that pitch with a PROPER HARD BALL. We were going to start with one of us bowling and the other one catching, just to get a feel for the ball, so Dad got ready to bowl and I got ready to catch. He ran in, turned his arm over and the ball pitched halfway down the wicket. Because of the green matting, it bounced a bit more than I expected and it leapt up and smacked me right in the chops. There was blood everywhere, I bawled my eyes out and we went straight home. So much for playing with a hard ball.

That might not have been quite as much fun as I had hoped, but the best cricket games I played with my dad were with a red Incrediball down at Post Hill, a short walk from our house. This was an overgrown field with trees all around it, and it was the place we used to go when I got my first dog, Pepper (there’s another dog to look up in the index). I’d been pestering Mum for years to let me have a dog and she finally let me when I was 13. Pepper was a crossbreed, part Staffordshire bull terrier, part Labrador, with a few more breeds thrown in as well, but he looked very much like a Rottweiler.

He was a lovely dog, very loyal and friendly, and he generally did as he was told. I trained him to fetch my socks and shoes for me, and when we went camping on a weekend (which was almost every weekend in summer), Pepper would bed down in my tent alongside me. We were very good pals. But probably the best thing about him was that he absolutely loved to chase and fetch a ball. So when we took him for walks down to Post Hill, Pepper became our fielder. Wherever we hit the ball, he’d sprint after it and bring it back to us. He was an absolutely brilliant fielder. He made Jonty Rhodes look like Monty Panesar.

Those games at Post Hill with my dad (and occasionally my mum) were incredibly well organised and we developed hundreds of rules over the years. As a bat, we used a stick that I’d found in the woods and ripped the bark off, about the size of a baseball bat. I think it was bent in the middle as well. Batting was a tricky business, because the pitch was nowhere near flat, there were stones all over it, so one ball could bounce over your head, then the next could roll along the floor.

Not only that, but we had the biggest set of stumps in the world. Whoever was batting would stand in front of a sapling that must have been three feet wide and six feet high. That was our stumps. So if Dad bowled me a bouncer, there wasn’t much point in me ducking underneath it because I’d be bowled out. And if the ball hit me on the shoulder, I could be lbw. As I said, batting was far from easy.

If you managed to connect with the ball, and sent it flying into the trees for Pepper to fetch, there were some trees that were out and other trees that were six. If you hit the ball over a track behind the bowler, that was six as well. And if you edged the ball, there was a bigger tree behind the sapling that served as a slip cordon. If you nicked it past the tree, you were okay, but if it so much as clipped a leaf, you were out.

As you can imagine, wickets fell at regular intervals in this game, so we played ten-wicket innings. I would bat until I’d been out ten times, then Dad would do the same and try to beat me. Fifty or sixty† all out could well be a match-winning score. I’m not sure who won the most games. I think that I did, but my dad would probably say that he did. Actually, why don’t I go and ask him? Or better still, I’ll ask my mum as well. I’ve a feeling that we might need an independent adjudicator.

| Me: | Mum, who do you think won the most games when we played down at Post Hill? |

| Dad: | I definitely won the most games. |

| Me: | I wasn’t asking you. |

| Mum: | Oh, I don’t know, it probably ended up about even. But it was always very competitive. Not just when you were playing cricket, either. Whatever you played together was competitive, even if you were just whanging a ball to each other on the beach. Most people just do that to play catch, but with you two there was always some sort of competition involved. |

| Dad: | That’s the way it should be. All games are competitive. |

| Me: | Did we have many arguments about the rules? |

| Dad: | No, because I was the sole umpire, so there were never any arguments. You just had to put up with that. |

| Me: | I must have won most games, though. You were useless. |

| Dad: | I wasn’t, I was absolutely brilliant. Unorthodox, maybe, but brilliant all the same. |

| Me: | You couldn’t bat for toffee. And you bowled like my mother. |

| Mum: | Erm, excuse me, Matthew. When I went down to Post Hill with you, I was going to walk the dog. I didn’t want to have to play cricket as well. |

| Me: | It was boring playing with you, Mum. I could just smack it anywhere when you bowled. |

| Mum: | Cheeky sod. |

| Dad: | My bowling was good enough for you most of the time, anyway. |

| Me: | That was because half the time you didn’t bowl it, you threw it. |

| Dad: | You’ve got a point there. I did throw it from time to time. |

| Me: | Yes, whenever there was a danger of me beating you. |

| Dad: | Well, if you’ve got a lad who can hit every ball when I bowled it, what was the point? I wanted to keep challenging you. And I didn’t just throw it, by the way, I sometimes threw it with sideways movement, so it spun as well. It was a good test for you. |

| Me: | Especially when the stumps were six feet high. And I bet when you were batting you wished that you’d never sorted out my bowling action in the garden that time. |

| Dad: | No, that was well worth the trouble. It was hard work, it took all Sunday morning, but we got there in the end. I got the run and jump sorted out, then I asked Bob Richardson about some of the more technical stuff. Bob taught at my school and he used to play in the Bradford League, so I’d ask him during the day about how to use the front arm, or how to hold the ball, and then I’d come home and tell you about it in the evening. You were a quick learner, but Bob deserves some credit. |

| Me: | Yes, he deserves some credit for me bowling you out all the time. |

| Mum: | Anyway, there were never any hard feelings when the two of you came back. You always seemed to have had a good time. And at least when you were playing down there, you weren’t throwing the ball against the kitchen wall or destroying the garden. |

| Me: | Oh yes, I smashed a lot of plants down, didn’t I? |

| Mum: | You smashed everything, even in the bits you weren’t supposed to go near. Anything with a head on it would come off. The daffodils never got near flowering, the gladioli never got a chance to come out. In the end, I just got some very low plants that didn’t have heads on them, so it didn’t make a difference whether they were hit or not. |

| Me: | I remember one time with the flowers as though it happened in slow motion. It was in the part of the garden that I wasn’t allowed to go in, but I’d been throwing the ball against the wall and bowled myself a wide, juicy half-volley. I really smacked the ball and it went directly towards some really nice flowers that you had. I knew as soon as I hit it that I was in bother. The ball seemed to travel in slow motion and it went ‘Pop’, straight against the flower, and the head fell straight off and tumbled to the ground. |

| Mum: | Funnily enough, I remember that as well. |

| Me: | Whenever I knocked the head off a flower, I’d pick it up and stick it back on top of the leaves, so it looked as though the flower hadn’t come off. I just hoped you wouldn’t notice. |

| Mum: | I always noticed, Matthew. Always. |

I’m not sure that leaves us any the wiser about who won the most games, but this is my book so I get the final word. I won the most games, but I might not have done if Dad hadn’t sorted my bowling action out in the garden. That seems fair enough.

Once I had got the hang of jumping rather than hopping, I used to spend ages practising in the garden, running in down the side of the greenhouse and bowling into a netting fence that we had. I had to be careful, though, because we lived in a semi-detached house and there was another garden right next door. I once bowled one that hit a ridge, bounced over the fence and smashed next door’s garage window.†

Mum and Dad still live in the same house and I was round there recently having a look at the garden, and it occurred to me that the layout there is probably responsible for a quirk that I have in my bowling action. I have a bit of a cross-action, in that my front foot goes across to the right too far when I bowl, across my body (compared with how a normal person bowls, anyway). It actually helps me to swing the ball and has helped in particular against left-handers, enabling me to get closer in to the stumps bowling over the wicket, giving me a better chance of getting an lbw.

In the layout opposite, the main set of arrows from top to bottom show my run-up and pitch in the garden. The two-way arrows towards the bottom show where I threw the ball against the kitchen wall and smacked it back across the patio. You can see there wasn’t a straight line coming down from the side of the greenhouse to the fence where the wickets were on the other side of the garden, so I had to adjust and come across myself in my action. It had never occurred to me until recently, but that could well have led to the way I have bowled ever since. So perhaps every time I dismissed Matthew Hayden when I was playing for England, I should have been thanking my dad for putting the greenhouse in such a daft place.

Not so far from our house, about a ten-minute walk (fifteen if you had a heavy bag), was our local cricket club, Pudsey Congs, which is where I went to start playing some proper cricket. I started going down there at the age of 11 and, to begin with, we played eight-a-side, sixteen overs per team, with four pairs of batsmen going in for four overs at a time, and losing eight runs every time one of them was out. From the first time I went, I was really keen, and I think Mum was even keener to have me out of the house. Soon enough, the cricket club became the centre of my little universe.

I was lucky to have such a good club just down the road. I suppose that anywhere you go in Yorkshire you’ll never be far from a decent cricket club, but I certainly couldn’t have done much better than having Pudsey Congs—or Pudsey Pongos, as we were known—right on my doorstep. It was a friendly place with a good family atmosphere, the bar would be full most nights and the first team played a very decent standard of cricket, in the Bradford League first division.

I worked my way up through the junior sides and was then drafted into the third team for a season when I was 15.1 played a couple of second-team games as well that year, but to my amazement, the next season I was fast-tracked into the first team by Phil Carrick, the former Yorkshire left-arm spinner who was captain of the club. Ferg, as he was known to everyone (think ‘Carrickfergus’), had obviously seen something in me that he liked.

I wish I was In Carrickfergus Only for nights in Ballygran I would swim over the deepest ocean…

I’d been a bit of a late developer up to this point. As well as my cricket, I’d done some judo and played quite a bit of rugby, but I gave those up because all the other lads were bigger and broader than me. From the age of 16, though, I really started to grow and, as a result, my bowling began to develop. To this day, I’m not sure exactly what Ferg saw in me, maybe just a big fast bowler’s arse and an ability to swing the ball.

I certainly used to swing the ball in the nets at Congs, but that might have had something to do with my special ball. There was one ball in particular that I used to keep for bowling with in the nets and I looked after it lovingly. At home, I would get Cherry Blossom shoe polish out of Mum and Dad’s cupboard, put a dollop of that on the ball and buff it up with a shoebrush. Then before nets on a Wednesday night I would give the ball one last polish with a shining brush, and make absolutely sure that nobody else nicked it when I went to practice. That was my ball and nobody else was getting their grubby mitts on it.

For all that Ferg whistled me up into the first team at Congs, for the first few games all I did was bowl two or three overs and spend the rest of the innings fielding, wondering when I was going to get another bowl. After a few games, I started to find this frustrating. ‘Ferg,’ I said, ‘why do you want me here playing a fifty-over game if I’m only going to bowl a few overs?’ The answer was that he was easing me in, allowing me to get a feel for first-team cricket before too much was expected of my bowling. He didn’t want to rush me because this was, after all, a very decent standard of club cricket, probably the best in Yorkshire (and therefore, so some locals would have you believe, probably the best in the world).

As the season progressed, I started to bowl a few more overs, but I was given an early idea of the quality I was up against when we played Spen Victoria. That was the game I came across Chris Pickles, the Yorkshire all-rounder who was coming to the end of his county career but spent his weekends terrorising club bowlers. He just used to come in and blast it; most of the grounds weren’t very big and he could smash 100 in no time.

I opened the bowling that day and had one of the openers caught at slip with a lovely outswinger (no shoe polish involved this time, just the new ball curving away nicely). Pickles was next in and he wandered out to ask the other opening batsman what was happening. ‘Oh, it’s just swinging a bit,’ his mate said.

I’d heard all about Pickles, so I ran in really hard at him next ball. The ball swung alright, and landed on a length, but he just plonked his front foot down the wicket, hit through the line of the ball and sent it soaring over cow corner, where it landed on top of some faraway nets. I couldn’t believe it. I just stood halfway down the wicket, hands on my hips, looking at him with a puzzled expression on my face. He ambled down the wicket, tapped the pitch with his bat, and muttered out of the corner of his mouth: Anti-swing device, son. ‘Antiswing device.’

So I was on a steep learning curve, but I loved the atmosphere and I just wanted to bowl. We had a good team, including former Yorkshire players like Ferg and Neil Hartley, and current ones like Richard Kettleborough, while James Middlebrook came up through the ranks with me. We also had some very useful overseas players, such as VVS Laxman from India and Yousuf Youhana from Pakistan. I’d be bumping into them again later in my career.

Lax was only 19 when he came to us, but it was clear he was a class act. After one game in which he’d scored a few runs and I’d taken a couple of wickets, we were chatting to Ferg in the clubhouse. ‘One day,’ Ferg said, ‘you two will play against each other in Test match cricket.’ We just laughed at him and told him not to be so daft. Lax had only played a handful of games and I was a raggy-arsed 17-year-old who’d just broken into Pudsey Congs first team, so it was a pretty outlandish thing to say.

The sad thing was that Ferg didn’t live to see his prediction come true. In January 2000, at the age of 47, he died after suffering from leukaemia. Less than two years later, I played for England in Mohali against an India team that included VVS Laxman.

He was a great man, Ferg, and I miss him terribly. It’s impossible to overstate his influence on me in those early days at Congs. He really took me under his wing. Whether we were out in the field or chatting in the bar after a game, he always had time for me. With my bowling, he would always emphasise to me the importance of length. ‘Length, Matthew, length.’ He’d tell me to go to the nets, put a hankie down on a length and see how many times I could hit it in an over. I used to spend hours doing that, going up to the nets at Congs after school and bowling on my own at a set of stumps with a hankie or a lump of wood on a good length. And then, when we were playing a match on Saturday, I would have Ferg standing at mid-off and growling at me. Even now, fifteen years later, when I bowl too short or too full, I can sometimes hear Ferg’s gruff voice grumbling in my ear: ‘Length, Matthew, length.’

But I must have been getting my length right most of the time, because in 1995, after only a couple of seasons in the first team at Congs, Ferg recommended me to Yorkshire. I was still only 18, doing the second year of my A-levels at Grangefield comprehensive, but when schoolwork allowed I was able to take the next steps of my cricketing education in the Yorkshire Second XI.

In general, club cricket with Pudsey Pongos prepared me pretty well for life on the county Second XI circuit. There were always new lessons to be learned, but I don’t remember feeling particularly out of my depth at any point, at least not from a cricketing point of view. But one thing that is drastically different about playing three-day matches, and spending a lot of time on the road as a result, is that you spend a hell of a lot of time with your team-mates.

This is a group of young blokes, many of whom are easily bored and need to find things to occupy their underdeveloped brains, a situation that inevitably results in a lot of practical jokes. For quite some time in the Yorkshire second team, I felt well out of my depth in terms of the pranks. And to make matters worse, the prankster-in-chief was the coach himself.

Doug Padgett was a coach from the old school, a former Yorkshire batsman who had been the club’s coach for donkey’s years and usually travelled with the second team. He was a good bloke, but he had a time-honoured way of making a new lad feel welcome.

Take the piss out of him whenever possible.

This is the man who would welcome a lad making his debut by sending him round to take the day’s lunch order. ‘Here, Twatook,’ he would say (he called all the younger lads Twatook). ‘Do the lunches for us, will you? Go round and see how many of the lads want steak and how many want salmon, then nip to the kitchen and tell the chef.’ So the new lad would eagerly set about his task, taking all eleven orders, only to find when he got to the kitchen that the only option available for lunch was lasagne, something that Padge and the other ten players were only too well aware of.

Another trick of Padge’s was to ask a new lad to go to his car and find out the Test score from the radio. James Middlebrook was one who stumbled into this trap. ‘Midders, Twatook, nip to your car and find out the Test score for us, will you? There’s a good lad.’ So off Midders trooped to his car and sat there for ages, frantically tuning and re-tuning the radio in an attempt to find Test Match Special. He returned slightly crestfallen, having failed in his mission.

‘Sorry, Padge, the Test match doesn’t seem to be on the radio today.’

‘No, Twatook, it wouldn’t be. They don’t play Test cricket on a Wednesday.’

A lesson swiftly learned for Midders, who would think twice before his esteemed coach sent him off on any errands again. I’d say I felt sorry for him, but most of us suffered in a similar way, some worse than others.

Midders got away lightly compared to the poor young whippersnapper who had travelled with Padge on an away trip to Glamorgan a few years earlier. This was before my time, but the tale was often told of an unnamed player—let’s just call him Twatook—who sat in Padge’s car for the long drive down to Wales along with a couple of his new team-mates.

As they travelled down the M5 and started to approach the Welsh border, Padge turned to the young lad sitting quietly in the back.

‘You have got your passport with you, haven’t you, Twatook? We’re about to go into Wales.’

‘Erm, erm, erm, no Padge, I don’t think I have,’ came the timid reply.

‘Oh Christ, didn’t anybody tell you? We’re going to Wales. It’s a different country. What are we going to do when we get to the border? We’re going to have to hide you.’

So Padge pulled his car over, opened the boot, moved several cricket bags to the back seat and told his victim to lie down in the boot until they had crossed the border. Young Twatook climbed in, snuggled down and Padge slammed the boot lid shut. He drove off into Wales, leaving his captive in the boot to think about the foolishness of forgetting his passport. Once the border had been safely negotiated—armed checkpoints and all—the hostage was released, poor lad. I’m sure Padge felt that it was all good character-building stuff.

Where Padge had led, there were plenty of disciples ready to follow, which has made the Headingley dressing-room a dangerous place to be at times over the last few years. Probably the biggest irritant in the Yorkshire team in recent years—myself aside—has been Anthony McGrath.

The problem with Mags is that he is easily bored and he likes to fill his time by pissing off his team-mates. A few years ago, one of his little pet projects was to put his team-mates’ cars up for sale in Auto Trader magazine, always at a bargain price carefully calculated by Mags himself. The advert for the car would usually say something along the lines of:

‘Owner forced to move abroad, Price reduced for quick sale. Please call…’

and then include the player’s mobile phone number. Inevitably, for such a bargain, these adverts attracted plenty of interest from potential buyers, prompting an endless stream of phone calls to the victim’s mobile. Time after time, he would have to say, ‘I’m sorry for the misunderstanding, but it’s not for sale.’ Which could be quite amusing on the first two or three occasions. But when it came to the 25th call in the space of an hour, it could start to become more than a little irritating.

Bogus adverts aside, Mags has often been implicated in one of the great scandals that has swirled around the Yorkshire team for several seasons now. This is the ongoing mystery of Jack the Snipper, a long-running case that has yet to be cracked and has baffled some of the finest criminal investigators in Yorkshire and beyond.

The culprit in this case is known to be someone with access to the Yorkshire dressing-room. He (or she?) waits until the dressing-room is deserted, then quickly seizes his (or her?) moment, moving in with a pair of scissors and snipping the toes off a sock belonging to the intended victim. When the victim goes to pull his sock on after the game, he pulls it up to his knee and realises, to his horror, that he has become the latest victim of JACK (OR JACQUELINE?) THE SNIPPER.

Understandably, nobody has ever owned up to these crimes, so the mystery remains unsolved. Police now suspect that the culprit may have multiple identities.

Not the most original of practical jokes, perhaps, but most of the Yorkshire players have seen it as a mildly amusing, relatively harmless gag if they happened to be a victim. But one season the Snipper targeted David Byas so many times that he no longer saw the funny side. Gadge, as he was known (for his extraordinary Inspector Gadget-like extending arms in the slips), was our captain at the time and, after his socks had been snipped for the umpteenth time, he decided the time had come to put an end to the tomfoolery.

In the build-up to one Sunday League game at Headingley, Gadge told us that we all had to be at the ground by 10 o’clock in the morning, even though the match wasn’t due to begin until 1.30 in the afternoon. It seemed a strange request, but Gadge was keen on punctuality, so everyone dutifully turned up at the appointed time. At which point the skipper took us all out to the middle of the ground at Headingley and asked us to sit in a big circle. He sat down with us and then told us why we were all sitting there looking as though we were about to play Pass the Parcel. ‘Right, you lot,’ he said, ‘nobody is moving from this circle until I find out which pillock has been snipping my f***ing socks. I just want to know who it is, then we can have a quick chat, move on and all go for some lunch.’ Nobody said a word. For a good few minutes there was complete and utter silence.

‘Come on,’ said Gadge, after a while. ‘I’m not joking here. We’re going to get to the bottom of this nonsense. Whoever has been snipping my socks is sitting in this circle and I want to know who it is.’

Still nobody said anything. There was another long, uncomfortable silence. After we’d been there for about half an hour, Gadge became more insistent—still reasonably calm, but the tone of his voice raised slightly. ‘Listen,’ he said. ‘If nobody has got the balls to own up to doing these stupid stunts, it’s a piss-poor effort. All you need to do is be big enough to own up, then we can move on.’

And still nobody said anything. We had probably been there for around an hour when Gadge started to get angry. ‘For f***’s sake,’ he said, ‘will somebody PLEASE tell me who has been snipping my f***ing socks?’

Once again, there was only silence. And I kid you not, we were sitting out on that field, in that circle, for three hours. THREE WHOLE HOURS! Eventually, at one o’clock, the opposition captain arrived out in the middle, asking if we were ready to toss up, and Gadge, as captain, had no option but to get up and leave us. So Jack the Snipper had slipped off the leash again and he remains at large to this very day. If you ever find yourself having to spend a day in or around the Yorkshire dressing-room, it may be worth your while packing a spare pair of socks.

The same season as that unfortunate incident, there was an outbreak of a similar—but unrelated—crime in the Yorkshire second team. At the time, I was in and out of the first and second teams, so I saw some of the events first hand and have called on extremely reliable witnesses to fill me in on the bits I missed. Again, this spate of crimes involved some tampering with the kit of a senior member of the dressing-room, but this time socks were not involved. This time the crime was theft and the stolen items were underpants belonging to Steve Oldham, Esso, the second team coach.

Pinching someone’s underpants might, again, seem like a fairly low-level jape, causing brief hilarity in the dressing-room, and mild irritation to the victim. But if you’re playing away from home for a four-day match and you have four pairs of undies stolen, it can be more than a little frustrating. It’s difficult to replace the pants, for a start, because you have to be at a cricket match all day while the shops are open, and a week without undies is, I imagine, not much fun.

And if, like Esso, this happens to you for seven four-day matches in succession, that’s twenty-eight pairs of underpants that have gone missing. Boxer shorts, Y-fronts, briefs; you name them, Esso lost the lot.

As you’d expect, Esso grew more and more frustrated as his stock of underpants became gradually depleted during the season. But he tried hard to keep his cool, to make it seem as though the thefts weren’t getting to him, to deny the prankster the satisfaction of seeing him upset.

That pretence of calm became harder to maintain once his pants started to reappear in increasingly unusual ways. The first pair was returned during a game at Bradford Park Avenue. Esso was sitting watching the game, when he casually glanced up at the flagpole and noticed a pair of his Y-fronts billowing in the breeze where the Yorkshire flag should have been. Nobody would own up to hoisting the offending item, so Esso made us all run around the ground for an hour in the pouring rain at the end of the day’s play.

The next second team game was at York and we travelled to the ground as usual in three or four cars. I was in one of the middle cars and Esso was in one of the cars further back. When we turned off the A64 for the last leg of the journey, we saw the road sign saying ‘Welcome to York’, but hung over the corner of the sign was another pair of Esso’s undies. I’m not sure whether he stopped his car to retrieve them or not, but at the end of the game at York we found ourselves running round the outfield again as punishment.

Perhaps the thief was starting to take pity on Esso by now, because the underpants were being returned to him on a regular basis. Never in a straightforward way, but at least he was gaining pants rather than losing them. I wasn’t around to see the next pair returned, but I heard that they were discovered during the second team’s next home game at Bingley, where the groundsman had a dog. At some point during that game, the groundsman’s dog was spotted running onto the field, wearing what looked very much like a pair of men’s briefs. I missed out on the post-match laps of the boundary that time, but by this stage Yorkshire’s second team must have been the fittest side on the circuit.

It was now getting towards the end of the season and, whether or not the thief was running out of ideas, he was running out of time to return the rest of his loot. Our final home game of the season was at Castleford and, when Esso drove into the ground, he was finally put out of his misery. Strung around the railings of the car park, like bunting at a school fair, were the remaining twenty-one pairs of underpants, good as new, ready to be reclaimed by their rightful owner, and Esso’s torment was at an end. Isn’t it nice when a crime story has a happy ending?

I don’t want to name names here in case anyone’s lawyer gets onto me, but there were strong suspicions that Alex Morris, our gangly all-rounder from Barnsley, may have been involved in these pranks. And Gareth Batty, the off-spinner, was also considered not to be beyond suspicion. But once again, the crime remained unsolved. For some reason, Alex left Yorkshire a couple of years later and moved to the other end of the country to play for Hampshire. Similarly, Batts soon departed to play for Surrey. I’ve never found out whether their departures were related to the case of Esso’s undies.

Once I had finished my A-levels in 1995, I spent most of the summers of 1996 and 1997 playing for Yorkshire’s Second XL I made my first-class debut in July 1996, against South Africa A, but didn’t get a run of games in the first team until a couple of years later. In the meantime, I was able to go back on a weekend and play for Pudsey Congs with Ferg and my mates. And that would invariably be followed by a good few beers in the clubhouse on a Saturday night, which I was quickly learning was all part of the fun.

By this time, a promising ginger-haired wicketkeeper called Matthew Duce had made his way into the first team at Congs. For me, as an outswing bowler, it is always important to have a decent wicketkeeper in your side to hang onto all those nicks, so Ducey was good for me because he had a safe pair of hands. And the fact that he had an attractive sister who would come to watch us was an added bonus.

Sarah was a similar age to me, she was single at the time, and this gave Ferg an idea. One Saturday, when we were playing away to East Bierley, I was sitting watching the game while we batted, and Ferg said to me: ‘I bet you couldn’t get a date with Ducey’s sister, Hoggy. No chance at all. In fact, I’ll bet you a fiver that you can’t.’

Unbeknown to Ferg, in the previous couple of weeks Sarah and I had already had a couple of liaisons that we had managed to keep a secret. But I wasn’t about to tell Ferg that, so the next week I turned up and was able to announce, to his astonishment, that I had indeed managed to get a date with the supposedly impossible Miss Duce, and I would be going out with her that evening. What a result! A date with an attractive girl and a fiver from Ferg already in my pocket to buy her a couple of bags of crisps. That must’ve been the easiest money I’ve ever earned.

Sarah and I soon became good mates and, for a girl, she wasn’t a bad ’un at all. I must have been keen, too, because I even started taking her along when I went to meet Ferg in the pub (yes, I knew how to show a girl a good time). I used to go to his local, the Busfeild [sic] Arms in East Morton, he would have a pint of Tetley’s, I’d have a pint of Guinness and we would talk about cricket, the universe and everything else besides.

Even once I was on the books at Yorkshire, if I ever needed a few words of wisdom I would go back to Ferg’s pub to chat to him, and Sarah would usually come with me. Halfway through the 1998 season, I was becoming fed up with the lack of first-team cricket I was getting at Yorkshire. I’d been doing well in the second team, but there were a lot of pace bowlers around at the time. There was Darren Gough and Peter Hartley opening the bowling, then Chris Silverwood, Craig White, Paul Hutchison, Ryan Sidebottom, Gavin Hamilton and Alex Wharf. It was an amazing crop of seam bowlers.

In one second-team game at Harrogate, I took seven wickets against Worcestershire and they expressed an interest in signing me. I asked Ferg for advice and he suggested that I should go down to Worcester with Sarah, have a look around the place and see what we thought. We went down there for a weekend, stayed in a hotel and had a chat to Bill Athey, who was Worcestershire’s second-team coach. He had played in that game at Harrogate and kindly missed a straight one that I bowled to him. We quite liked the look of Worcester, but I went back to Yorkshire and told them my situation, and they persuaded me that I still had a good chance of playing in the first team. We mulled it over and eventually I decided to back myself to succeed at Yorkshire.

So Sarah and I were very much an item by now and before long I was invited for a game of golf with her dad, Colin. We went to play at Gotts Park in Leeds and it soon became apparent to me that I was dealing with a family who weren’t backwards in coming forwards when Colin told me that he had had a vasectomy. Why did he need to tell me that? I’d only just met the bloke, and I barely knew what a vasectomy was, but Colin clearly decided that it was something I needed to know. There must have been a long and awkward silence while I worked out what I was supposed to say in response. In the end I probably just grunted.

Things didn’t get any better once the golf started. On one of the early holes, he played his tee shot, then wandered off to the right and rested his three-wood against his golf bag. I told him he’d be well advised not to stand there, because I never really knew where I was going to hit the thing. So he stepped back a couple of paces, and it was a good job he did. From my tee shot, I whacked the biggest slice imaginable. The ball flew off at 45 degrees and smashed straight into Colin’s three wood. It was a freakish shot, it hit bang smack in the middle of his carbon shaft and the club snapped clean in two.

Not the best of impressions to make on my prospective father-in-law.

But at least Colin seemed to like me, which was something that certainly couldn’t be said of Sarah’s mum, Carole, in those days. She had found out about the start of our relationship while she and Colin were away on holiday in France. Sarah hadn’t gone with her, so Carole phoned up while she was away to check that all was well.

‘How are things at home?’ she asked Sarah. ‘Any news?’

‘Not much really, Mum,’ said Sarah. ‘Oh, except I’ve got a new boyfriend.’

‘Oh, that’s nice. Anyone I know?’

‘Well, yes, you know of him.’

‘Is he from the cricket club?’

‘Yes, he is.’ There was a short pause while Carole worked out the likely candidates.

‘And will I like him?’ she asked.

‘Erm, not sure, Mum. I think you will.’

‘Oh, Sarah, please don’t tell me it’s that Matthew Hoggard. That boy is so rude. And he’s always drunk.’

‘Er, yes, I’m afraid it is him. Sorry, Mum.’

So even from that early stage, Sarah was feeling the need to apologise for me. But I’m glad to say that the relationship with my in-laws has progressed considerably since those first days. We get on like a house on fire now and I couldn’t wish for better in-laws. I still regularly play golf with Colin—the Badger, as he has come to be known, because he’s as mad as a badger about his cricket, buying a season ticket for Yorkshire and sitting in the same seat at Headingly all summer. I also still play cricket with Ducey, Sarah’s brother, when I can. As for Carole, I gradually managed to persuade her that I wasn’t always drunk and that I wasn’t quite as rude as she had first thought. I’ve got absolutely no idea what gave her those impressions in the first place, no idea at all. She eventually realised what a fine, upstanding, polite, charming, sober, intelligent individual I was. But it’s a good job that Sarah didn’t listen to her mother’s advice on everything, or I don’t think our relationship would have lasted too long.

†HOGFACT: By the time they reach the age of SIXTY, most people’s sense of smell is only half as effective as in their younger days. As you can tell by the aftershave that old blokes wear.

†HOGFACT: In Massachusetts, snoring is prohibited unless all bedroom windows are closed and securely locked. I’m led to believe that a man’s punishment for this crime is a slap from the wife.