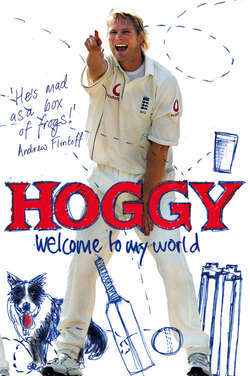

Читать книгу Hoggy: Welcome to My World - Matthew Hoggard - Страница 13

3 Wild and Free

ОглавлениеI can remember coming of age clearly, because turning 18 hit me with a thud. The precise moment that the thud occurred was during my 18th birthday party at Pudsey Congs clubhouse (where else?). I was standing on a chair, getting carried away dancing to Cotton-Eyed Joe, and I smashed my head on the fire exit sign. Not quite behaving like a proper grown-up yet, then.

Unsurprisingly, it was Ferg who decided that the time had come for me to broaden my horizons beyond the playing fields of Yorkshire. I’d played my first few games for the county Second XI in the summer of 1995, and not done too badly, but I was still extremely raw, both as a bowler and as a lad.

So Ferg got in touch with Richard Lumb, his old Yorkshire teammate, who had moved out to South Africa and was involved with the Pirates club in Johannesburg. ‘Hoggy, it would do you good to go abroad,’ Ferg said. ‘I’ve sorted you out a club in South Africa, You’ll have a great time. See you in six months.’ And that was pretty much that.

I spent two winters with the Pirates, then returned to South Africa a couple of years later in 1998, a little less raw, for the first of two seasons playing first-class cricket with Free State in Bloemfontein. Both of them were fantastic experiences which, in different ways, helped me to find my way in the world.

My first spell in Johannesburg, shortly after I’d done my A-levels in 1995, was the first time I’d lived away from home. It was also the first time I’d been in an aeroplane. We’d been on umpteen family camping holidays to France when I was younger, but we’d always driven in the car and I’d never been up in the skies. My mum and dad drove me down to Heathrow, and by the time we got to London, I think my fears had gradually given way to excitement. Never mind the six months away from home, I thought, I’m actually going to go up in an aeroplane! Nneeeeeooowwwmmmm!

When I landed at Johannesburg airport, I must have come across like a little boy lost. For what seemed like ages I was looking for Richard Lumb and he was looking for me, both of us without success. He was going round asking anybody with a cricket bag—and there were quite a few—if they were Matthew Hoggard; I was going round looking for a tall bloke with grey hair, and there seemed to be plenty of them as well. Eventually, we found each other and got into his car. We got lost on the drive away from the airport, but he finally managed to take us to the famous Wanderers club, where he set the tone for my trip by buying me lunch and a beer or two.

And that was to become my staple diet for much of my stay in South Africa. Not so much the lunch; just the beer.

I don’t think I’d been warned, by Ferg or anyone else, just how much the South Africans like their beer. They must be the thirstiest nation on earth. Given the chance, they’d have beer for breakfast, and plenty of them do.

Before I’d even played a game with my new team-mates at the Pirates, they took me out to welcome me to the club. We went to the bar at the Randburg Waterfront, a lake just outside Johannesburg with loads of bars and restaurants around it. The evening started with a few convivial drinks, which helped me to relax as I was introduced to these strange people who, like it or lump it, were to become my new friends.

After we’d been in the bar for a couple of hours, I felt myself being shepherded towards the stage. When I was up there, everyone started singing, and I was given a half-pint glass full of the most disgusting-looking green drink. I had no idea what was in it, but something in it had curdled. I later found out that they had gone along the top shelf of spirits and topped up the glass with Coke. Yum yum.

The whole pub was singing at me to down it, so what else could I do? I remember drinking it, but I don’t recall much after that. I just remember waking up in the morning feeling very, very ill. But that had been my initiation ceremony at my new club. Welcome to the Pirates.

The problem was that just about every week seemed to be an initiation. The first game I played was for the club’s second team, so they could have a look at what I was capable of (and perhaps to check that I was still able to bowl a ball in a straight line after my ordeal at the Waterfront). That first game was away from home against Wits Technical College and, in one of those strange coincidences that cricket often throws up, also making his debut for Pirates that day was Gerard Brophy, who a couple of years later would be my captain at Free State and a few years after that came to keep wicket for Yorkshire.

I was quite surprised to find that it was really cold that day. I hadn’t initially planned to pack my cricket jumpers, I just expected it to be baking hot all the time, but I was glad I’d shoved them in at the last minute because it was bloody freezing. Anyway, both Gerard and I did the business on our debuts: he got 100 and I took four wickets.

So the cricket had gone well, but what really got to me was the fines system in the clubhouse afterwards. This was basically an excuse (yet another excuse) for making people drink vast quantities of beer, as decided by the fines-master of the day. Fines would be handed down for stupid comments made during the day, for embarrassing bits of fielding or for any other random transgression that could be deemed punishable by beer. This wasn’t something I’d encountered back at Pudsey Congs. Depending on who the fines-master was for that particular game, the punishment for a brainless comment would probably be to down a bottle of Castle. And that stupid shot you played? Oh yes, you’d better down another bottle for that as well. Needless to say, there was no mercy shown to the newcomers.

The worst offender for each game would be sentenced to death, which meant downing a beer every five minutes. The fines-master would have a watch, and every five minutes a cry of ‘Cuckoo, cuckoo!’ would ring out, signifying that the victim had to stand up and sink another bottle of beer. This would continue for as long as the fines session lasted, sometimes well over an hour. And to thank us for our sterling contributions in our first game for the Pirates, both Gerard and I were sentenced to death that day. So that was Initiation Mark II and another grim hangover the next morning. And there would be plenty more of those to follow.

Throughout my first year in Jo’burg, I stayed with the club chairman, Barry Skjoldhammer (pronounced Shult-hammer) and his family, his wife Nicky, their daughter Kim who was 11, and her brother David, who was 9. I’m not sure they knew what they were letting themselves in for when they agreed to take me in, but they were absolutely fantastic to me and treated me like one of their own. They had a nice house, a games room with a pool table, their own bar and a nice garden with a swimming pool. Life was good. They even took pity on me one morning after I’d come in from a night out at 5.30 a.m. The front door had been bolted and I couldn’t get into the house, so I kicked Sheba, the family dog, out of her bed on the veranda and curled up there for an hour before everyone else woke up. I wasn’t sure what Nicky would say when she found me lying there at 6.30 a.m., but she actually told me off for not waking them up to let me in.

After about three months, the chance came up for me to move out and go to stay in a flat with Alvin Kallicharran, who was also playing club cricket out there. By now, the Skjoldhammers knew that I was a bit wet behind the ears because they said that they wanted me to stay with them so they could keep an eye on me. And no way did I want to go: I got cooked for, I got lifts everywhere, there were kids to play with and they were lovely people. It was great. Even now, I look on the Skjoldhammers as my second family.

It wasn’t just at my new home that I was made to feel welcome. Although it may seem as though they were setting out to kill me with alcohol (I survived more than one death sentence), I couldn’t have been happier with the Pirates.

For a start, we had a very decent team. When they weren’t playing for Transvaal, we had Ken Rutherford, the former New Zealand captain, Mark Rushmere and Steven Jack, who both played for South Africa, and a few guys, like Paul Smith, my fellow opening bowler, who had played for Transvaal.

I also managed to take a few wickets, which helped me to be accepted quickly. It didn’t take me long to adjust my bowling because conditions suited me nicely. We were at altitude in Jo’burg, where the ball tends to swing more in the thinner air, and I was fairly nippy in those days and generally caused a few problems.

It was quite a different club from Pudsey Congs. Back home, I’d been used to there being lots of families around on a weekend. Cricket matches were a family day out on a Saturday and there would always be wives and kids in the clubhouse after the game. Pirates was a bit more spit and sawdust. The wives might come to watch for a while, but the club was mainly frequented by men. For me, that was just part of the learning about a different cricketing and social culture.

There was always a great atmosphere at the club. We used to play our games over two days at a weekend and, as a bowler, there was nothing better than getting your overs out of the way on a Saturday, then turning up on a Sunday morning to watch the batsmen do the hard work, especially as play started at 9 a.m. on the second day.

The Pirates’ ground was in a bowl, so we used to sit up on the banking and start up a scottle braai, a gas barbecue with a flat pan on top, and cook up breakfast for everyone. We’d take it in turns to get the bacon, the eggs, the sausages, and fill our faces with sandwiches while the batsmen went out to do their stuff. I would lose count of the number of times that someone would have just got a sandwich in their hand and a wicket would fall, prompting a distressed cry of: ‘Shit, I was looking forward to that sandwich. Can someone hold onto it for a while?’

I wasn’t paid to play for Pirates and I lived rent-free with the Skjoldhammers, but I did a few odd jobs to pay for my beer money. I helped out at Barry’s Labelpak business, for example, putting together packs of flat-packed furniture, I coached the Pirates kids on a Saturday morning and also did a bit of coaching at Rosemount Primary School during the week. At the school, I remember clipping one irritating lad round the back of the head when he wouldn’t do as I told him. I then got a bit worried when he said: ‘I’m going to go and tell the headmaster you did that.’

Fortunately, the headmaster was Paul Smith, the Pirates’ opening bowler. When the young lad went into the headmaster’s office, he said: ‘Mr Smith, Mr Hoggard just hit me round the back of the head.’ So Smithy hit him round the back of the head himself and said: ‘Well, you must have deserved it then. Now get back to your lesson straight away.’ Good job that wasn’t a few years later. I’d probably have got a lawsuit for doing that nowadays.

The best job I had in Jo’burg was being a barman at the Wanderers’ ground for the big games there. The Pirates had a box and, naturally, they asked me to man the bar. I can’t say it was the most taxing of jobs. I didn’t even have to take cash because there was always some sort of raffle ticket system in operation. I just had to open a few bottles of beer, pour the occasional glass of wine and watch a lot of cricket. And it just so happened that England were touring South Africa that year, so I got to spend a full five days at the second Test when Mike Atherton and Jack Russell staged their famous rearguard action. They certainly worked a lot harder out there than I did up in the bar.

But the important thing about my jobs was that they gave me enough beer money to take advantage of the opportunities for socialising provided by my thoughtful Pirates team-mates. There were plenty of them. Sometimes, I would go out the night before a game with the Smith brothers, Paul and Bruce, and we would put our cricket kit in the car before we went out. That way, we could stay out until the early hours, then drive to wherever we were playing, get a few hours’ kip in the car and wait for our team-mates to wake us up when they arrived. One important part of the procedure was that, before you went to sleep, you had to make sure that your car was under a tree and facing west, so you wouldn’t get burned by the sun when it came up in the morning.

Drink-driving was just not an issue in South Africa in those days. There would be times when we would go on a night out and, while we were driving from one bar to another, everyone would jump out of the car at a red traffic light, run around the car until the lights turned to green, then the one standing nearest the driver’s door had to jump back in and start driving. Everyone else had to squeeze in as well if they could and, if they didn’t, they were left behind. There would be people jumping through windows, hanging onto the roof. We obviously thought it was funny at the time, but it seems like absolute bloody madness now.

Another time when I was out with Bruce Smith, we’d ended up in the Cat’s Pyjamas (nice name), a 24-hour drinking place. For some reason, Bruce suggested we go to the Emmarentia Dam, which was a short drive away. He dared me to swim the 30 metres or so across it, run round a lamppost at the other side, and swim back again. In the clear-sighted wisdom created by God-knows-how-many bottles of Castle lager, I said I’d do it, as long as he did it with me.

We parked up by the dam on an empty side street, took our clothes off in the car and walked to the dam, stark bollock naked. We started swimming across the dam and I was going fairly well, thinking: ‘Yep, this isn’t so bad, I’ll manage it no problem.’ Then it suddenly started thundering and lightning, which made me think we ought to get a move on. We swam across to the other side of the dam, ran round the lamppost and had swum halfway back across the other way when lightning struck the dam. I’ll never forget that feeling when the shock got through to me, sending tingles throughout my body. Even in my less-than-sober state, I was more than a bit worried. ‘Do you feel all right?’ Bruce asked me. ‘Erm, yes, I think so,’ I lied back.

We were even more worried when we approached the shore and saw a police van parked up near our car. The policemen were wandering around, shining a light into the car and checking the surrounding areas. We stayed in the water† and hid in the reeds at the edge of the dam. ‘If I get caught here, stark bollock naked,’ I thought, ‘I really am in trouble.’ The police seemed to be there for ages and we ducked down every time they shone their torches towards the water. Thankfully they went eventually without spotting us and we scuttled off home to bed, feeling a lot more sober than we had done an hour or two before.

I suppose that these days were my first real taste of freedom, the slightly wild days that everyone needs to get out of their systems. No real responsibilities, no ties, just a fantastic opportunity to make the most of. Some people get that when they go travelling or to university; I was being educated in a rather different sense, concentrating my studies on taking wickets and downing beer.

I even ended up smoking cannabis once or twice, something I’d never even encountered back in Pudsey. And I’ll never forget the first time I tried it, with a bloke called Dean who I played indoor cricket with. We’d been out drinking and playing pool, and Dean then drove us in his VW Beetle to the top of a multi-storey car park that had amazing views over the whole of Jo’burg. He then took his weed out and rolled us a joint. In South Africa, the cannabis is so cheap that they don’t tend to mix it with tobacco, they just smoke the stuff on its own, which makes it pretty powerful, especially if you’ve never touched the stuff before. Dean had certainly touched the stuff before; I hadn’t.

Unsurprisingly, it hit me in a big way. To start with, I got the giggles, uncontrollably. Whatever Dean said, it made me double up with laughter. We then went on to a 24-hour kebab and burger joint to satisfy our munchies. I remember ordering my kebab, sitting down for a while and then walking up to collect my food. All of a sudden, I started to feel really ill. I was going to pass out and I started to panic, thinking of all the stories you see on the news of people who die the first time that they take drugs. And I distinctly remember thinking:

‘I’m going to die, I’m going to die! I don’t want to die, I’m too young to die! What will my mum and dad say if I die like this, slumped in a kebab shop after taking drugs?’

As far as I know, I didn’t die on that occasion. I was woken up shortly afterwards by a big fat bloke handing me my kebab. But it shows how naïve and inexperienced I was that I thought I might be killed by smoking cannabis for the first time.

And so my education continued. I’d better say at this point that, while all these shenanigans were going on away from the cricket field, I was still doing my stuff for the Pirates on a weekend. Both seasons that I was there I ended up as the club’s bowler of the season, something that still makes me proud when I think of it. If you’re turning up to a place where nobody knows you from Adam, the best possible way to make yourself popular is to prove you’re worth your salt as a cricketer.

But more importantly, I really did learn a lot more than just how to live the high life in Jo’burg. Those stories are just the silly bits that stick in my memory the best. But my eyes were opened in a much broader sense by having to make friends in a foreign country, by learning the culture, working out what makes different people tick and how to fit in with them yourself. And I was doing this all on my own. I might not have had much in the way of responsibilities in Jo’burg, but the experience made me much more capable of standing on my own two feet in the future. It’s an experience that gave me a lot of confidence and one for which I shall always be extremely grateful. So thanks again, Ferg, another masterstroke.

If those two years in Jo’burg helped to broaden my views of the world in general, it was during the two seasons I spent playing for Free State in Bloemfontein that I learnt some of my most enduring cricketing lessons. I was much more sensible there. The focus was well and truly on the cricket.

Apart from the fact that I was playing in the first-class game rather than club cricket, the pitches were much more challenging for a seam bowler. Whereas in Jo’burg I’d been bowling at altitude, swinging the ball around on pitches that were often green mambas, in Free State there was no altitude and the tracks resembled the Ml. They were flat, flat, flat, so you had to do a bit more than run in and turn your arm over if you were going to get a decent batsman out.

Ironically, it was bowling on a seam-friendly wicket at Headingley that had got me an invitation to Bloem in the first place, which was a complete and utter fluke. In August 1998, seventeen months or so after I’d finished my second season with the Pirates, South Africa had just lost a Test series in England and were having nets at Headingley before the start of a one-day series with England and Sri Lanka. By this time I was 21 and I wasn’t quite a regular in the Yorkshire side, but I was getting there.

When the South Africans were in town, I was just coming back from injury and it was suggested that I go and bowl at them in the nets at Headingley. As they were preparing for a one-day series, I was bowling with a white ball and the practice pitches at Headingley were sporting, to say the least. It was swinging and seaming all over the place. I steamed in and I must have bowled out every South African batsman, more than once in some cases. Shaun Pollock, Jonty Rhodes, Hansie Cronje: it was quite a list of conquests. They made me look like the best bowler in the world. It was extremely generous of them.

South Africa’s bowling coach on that tour was Corrie van Zyl, who was also a coach at Free State. After I’d finished bowling, he wandered up to me and casually enquired whether I had any plans for the winter. I didn’t, as it happened, so he asked if I fancied going out to Bloemfontein to act as cover for Free State’s bowlers. Given the time I’d had out in South Africa before, this was an opportunity that I wasn’t going to pass up. A couple of months later, I was on my way back there.

I had to bide my time once I’d arrived, though, because the Free State management were reluctant to pick an overseas player ahead of the established locals, particularly in the SuperSport Series, the four-day competition. But I was bowling well in the nets, I turned in some decent figures in one-day cricket and took plenty of wickets in club cricket for the Peshwas. Above all, on those hard, flat pitches, I was learning the value of bowling maidens, boring a batsman out and making him give his wicket away.

I wasn’t given a real run in the four-day stuff until February, but in my second game, against Eastern Province in Bloem, I got five for 60 in the first innings and two for 19 from twenty-one overs in the second innings. They couldn’t really drop me after that.

I was lucky at Free State to play with some very handy cricketers and, when we were at full strength, we had a pretty powerful side. If they weren’t away on international duty, we had Gerry Liebenberg as captain, Hansie Cronje, Nicky Boje and, best of all for me, we had Allan Donald.

Just to turn up at the Free State nets and watch AD go about his work was an inspiration. At the time, there was no bigger superstar in South African cricket, but he would have as much time for a young lad at the Bloemfontein nets as he would for Hansie Cronje. A nicer, more modest and down-to-earth bloke you couldn’t ever wish to meet. Within a few weeks of me being there, AD had roped me in as a babysitter for Hannah and Oliver, his kids, while he and Tina went out for the evening. We’ve been firm friends ever since.

He was also a real help with my bowling. When I arrived in Bloem, I was having a few problems with my run-up and bowling lots of no-balls. To my amazement, AD took me to one side and took a load of time to help me get it right. He moved markers, watched my take-off and landing, and helped me to work out how I could find my rhythm. With his help, I soon got myself sorted.

He also gave me a few tips on reverse-swing, which I didn’t know much about in those days. I was playing in one game at Goodyear Park when AD was just watching, playing with his kids on the boundary and having a drink with the groundsman in the family enclosure. I was bowling at the time but, in the overs in between, I was fielding on the third-man boundary and I signalled to AD to come over for a chat. He came down and I said to him: ‘Al, I need to know something. It’s reversing out there, and I know how to reverse it in to the batsman, but how can I get it to go away?’

‘You know how you try to bowl inswingers with a normal ball, pushing it in with your fingers and your wrist?’ he said. ‘Well, just turn the ball over so the shine’s on the other side and try to do that. You watch, it’ll swing the other way.’

So halfway through my next over, after I’d bowled a couple of inswingers, I did exactly as he’d said. Would you believe it, the ball swung the other way, the batsman got a big nick and was caught behind. The first bloody ball I’d tried it! I yelled in celebration, turned round and pointed with both hands at AD in the family enclosure, where he gave me the thumbs-up back.

In one-day cricket, he used to bowl as first change while I shared the new ball with Herman Bakkes, another right-arm swing bowler. But in one particular one-day match, not long after I’d arrived there, we were playing at home against KwaZulu-Natal. They had a dangerous pinch-hitter called Keith Forde who opened the innings and Gerry Liebenberg said that we wanted our best bowlers bowling at him, which meant AD taking the new ball instead of me. Fairly understandable, I suppose, but I was still a bit pissed off at the lack of confidence shown in me.

Anyway, within the first couple of overs, Herman got Forde out, clean bowled, and Gerry said, ‘Get loose, Hoggy. You’re on at AD’s end next over.’ So I warmed up quickly and, with my third ball, I trapped their number three, Mark Bruyns, lbw plumb in front. As we celebrated the wicket, Gerry came up to me and said: ‘Hoggy, I know you’ve just taken a wicket, but they’ve got Jonty Rhodes coming in next. We want our best bowlers bowling at him, so you’re coming off at the end of this over and I’m bringing AD back on.’

Now that really did piss me off. I went back to my mark in a huff and steamed in at Jonty. His first ball was outside off stump and he left it. The next one nipped back into him and ripped out his middle stump for a duck.† I sprinted down the pitch, arms in the air, and went straight to Gerry, who was keeping wicket, and shouted: ‘JONTY F***ING WHO?’ I think Jonty heard me on his way off and, a couple of years later, I did offer a belated apology and explained why I’d reacted like a nutter. I was a teensy-weensy bit wound up at the time. I think I’d made my point to Gerry in the best possible way and I was allowed to complete my spell, so on that occasion at least AD had to wait his turn.

No doubt about it though, AD will go down as one of the real good guys of the game. The same probably can’t be said of Hansie Cronje, although I have to say I was as shocked as anyone when all the stuff about his match-fixing was revealed. I got to know him fairly well, or so I thought (as did many other people). When you share a dressing-room with someone, you tend to think that you know someone pretty well, but that certainly wasn’t true in Hansie’s case.

He was captain of South Africa while I was at Free State and you could see why everyone thought so highly of him as a skipper. He was a really positive character, building everybody up so they felt good about themselves. Funnily enough he was also big on discipline, drilling it into everyone that you should always arrive early, whether it’s for a practice or a game, to make sure that you’re in the best possible frame of mind. I liked the guy and I was absolutely flabbergasted when the news broke of his wrongdoing. I would never have guessed it of him.

I mentioned a little earlier that, off the field, my time in Bloemfontein was spent much more sensibly than those slightly wilder days in Jo’burg. That was partly because I was a couple of years older, partly because the cricket was more serious and partly because Sarah came out to stay with me in Bloem, so I had someone to keep me company in the evening.

Having said all that, our time in Bloem was not without its incidents, often involving cars rather than alcohol (and not the two mixed together this time). One such escapade occurred in my second season with Free State, in 1999-2000, at the same time as England were playing a Test series in South Africa. I was driving with Sarah down from Bloemfontein for a few days’ break in Cape Town, which is about a ten-hour drive. At least, it should be a ten-hour drive, but I got badly lost, so it mushroomed into the small matter of a thirteen-hour drive.

To try and make up for lost time, I ended up in a bit of a hurry, and whenever I got the chance to put my foot down I put it ALL THE WAY down. We had a motor that could shift, because we were in a BMW belonging to Andy Moles, the Free State coach. For most of the journey, Sarah was fast asleep alongside me because we’d been out with Molar the night before and she was suffering. Or maybe it was the quality of the conversation that was sending her to sleep. Occasionally, she’d open her eyes and say: ‘Slow down, will you, Matthew? You’ve got to keep an eye out for the speed cops.’ So I would slow down while her eyes were still open, then speed up again when she went back to sleep.

Sarah must have been dead to the world when I came to one massive straight road, like a huge wide Roman road, on which there was no other traffic whatsoever for miles and miles and miles. I put my foot down and had reached about 180 kph (about 110 mph) when a policeman stepped out from behind a bush with a cardboard sign saying: ‘Stop!’ Sounds like a cartoon, I know, but it felt real enough at the time. I slammed on the brakes and managed to come to a halt—about half a mile down the road—and reversed all the way back to say hello to the nice policeman.

Once he’d established that I wasn’t a local, he said: ‘Have you got your passport on you?’

I said no, even though my passport was with my kit in the boot of the car.

‘Have you got any other ID?’ he said.

I gave him my international driver’s licence.

‘What are you doing over here?’ he asked, and I told him that I was playing cricket. He thought for a moment or two, while he wrote out a speeding ticket, and then said:

‘Hey, you’re not here playing for England, are you?’

‘Yep, I sure am,’ I lied again.

The policeman paused for thought again, then started smiling. ‘Oh, I don’t think you need to worry about that ticket, then. You can tear it up, on one condition.’

‘What’s that?’

‘You give me your autograph.’

So I gave him my autograph, shook his hand and got back in the car. I just counted myself lucky that he didn’t know enough about the England team—or the Free State team, come to think of it—to realise that I was telling him a fib. I hate to think of him sitting down to watch the Test match, telling his mates he’d got one of the England players’ signatures, then discovering that he’d actually been diddled and the bloke whose autograph he had was playing a game in front of two men and a baboon down in Cape Town.

I imagine he’d have been pretty peeved, but I hope he didn’t rip the ticket up and throw it straight in the bin, because a few months later I made my Test debut. My autograph might actually have been worth having then…

†HOGFACT: There are more atoms in a teaspoon of water than there are teaspoons of water in the Atlantic Ocean. I know, I’ve counted them.

†HOGFACT: In Minnesota it is illegal to cross state lines with a duck on your head. Well, why wouldn’t it be?