Читать книгу The Street Philosopher - Matthew Plampin - Страница 15

Оглавление2

The lamplighters had just finished their work on Mosley Street, affording Jemima James a clear view of the crowd that burst excitedly from a side alley, quickly flooding the pavement and overflowing into the path of the early evening traffic. It was comprised of working people, in jackets of canvas and fustian; Jemima sat up, imagining at first that a disturbance of some kind was spilling over from a back-street pot-house. But no–she soon saw that this crowd were working together, towards a unified and compassionate purpose. They bore a man between them, lifting him up almost to shoulder height. He was a soldier, and no private of the line; the gold on his uniform suggested a captain at least. His face, beneath some outlandish military whiskers, was all but white, and an elderly woman was pressing a bloody rag against his side.

Jemima rose to her feet. Her face was now so close to the office window that her breath misted on its surface. ‘Dear God,’ she said. ‘Be quiet for a moment, Bill, and come see this.’

Somewhat piqued, her younger brother stopped his story (an inconsequential piece of gossip to which Jemima had hardly been listening), crossed his arms and pointedly did not get up. He sat surrounded by boxes and parcels, the fruits of a long afternoon spent in the city’s finest dressmakers, milliners and tailors. Jemima had endured many hours of solemn, tedious debate over the merits of ribboned flounces, pagoda sleeves and the like, longing all the while to be back in her rooms at Norton Hall, out of her corset, deep in a book or periodical. Bill, however, loved these expeditions. That day, he’d even arranged his own appointments so that he could attend hers as well, and had been a terrible pest throughout. She simply could not be trusted, he’d declared, to select something suitably of-the-moment for the Exhibition’s opening ceremony, which was sure to be the event of the season–and if she looked dreary and widow-like before Prince Albert, he would never forgive himself. It had been an outright clash of wills, resolved only by uneasy compromise.

Jemima considered Bill. He was sprawled in his chair, glowering back at her. As usual, his clothes were of the very best quality, and included precious dashes of taste and individuality, like his purple silk necktie and the faint navy stripe in the grey of his trousers. Not for the first time, Jemima wondered what their father honestly made of this dapper son of his, who had no profession yet spent so much of his time in town, and who at twenty-six years of age had never once been linked to a member of the fairer sex.

‘I am going outside,’ she announced, ‘to find out what has happened, and who that poor man is.’

This succeeded in prising Bill from his seat. He crossed the office, glancing at the commotion in the street. ‘Is that really wise, Jem? It is Saturday evening, y’know. The mills will just have let out, and the liberated operatives will be debauching in their usual boisterous manner.’

‘Your intimate familiarity with the habits of the labouring classes never ceases to astonish, William.’ Jemima retied her bonnet. ‘I’m sure that we will be quite safe on Mosley Street.’

Bill, checked by this oblique reference to his more clandestine pursuits, swiftly changed tack, arguing instead that the carriage would be there for them at any minute. They could hardly afford to be wandering off into the city when Father would surely be expecting them at dinner. Jemima ignored him, knowing he would follow anyway.

Mosley Street, unquestionably one of Manchester’s finest, was home to a number of the city’s most august businesses and banks, as well as several prominent cultural societies. The facing rows of grand buildings, many fronted with columns and marble, blocked out all sight of factory chimneys. The crowd bearing the injured officer had come to a halt before the shadowy portico of the Royal Institution. Some began calling loudly for the police–rather unnecessarily, as every constable in the vicinity was already converging upon them with all speed. The victim was set down on the pavement; Jemima watched as the constables tried to reach him through the thickening circle of onlookers. There was a ragged clamour of voices as a dozen different accounts of the attack were delivered at once. After a few seconds of this, a short bulldog of a police sergeant shouted sternly for silence, and then began methodically to extract what solid information he could, devoting much of his attention to the old woman who still tended to the officer’s wound.

All traffic along the street had come to a halt. Jemima took this opportunity to cross, with her brother a step behind her.

‘By Jove,’ muttered Bill as they drew near. ‘I believe I know that fellow. Saw him in Timothy’s only a couple of hours ago, in fact, having a new dress uniform fitted for the Exhibition’s opening ceremony. He’s from the 25th Manchesters–a major. Name’s Raleigh, Raymond, something like that.’

The sergeant conscripted a dray that had stopped close by to convey the injured major up to the Infirmary at Piccadilly. As the driver began shifting aside the crates that were stacked in his vehicle to make room for his passenger, the major was lifted again. Under the sergeant’s careful direction, he was moved slowly to the rear of the cart, past where Jemima was standing.

Finding a last reserve of strength, the major made a feeble attempt to squirm free. ‘Get that blackguard away from me,’ he croaked desperately. ‘Keep him away, damn you!’

The sergeant had noticed Jemima; she was conspicuous on the fringes of that humble crowd. He now shot her an apologetic glance. ‘Excuse the language, ma’am. He’s in a state o’ considerable confusion. Sure ye understand.’

Jemima looked around. ‘Who could he be referring to, Sergeant?’

The policeman jerked his head towards a jacketless man sitting on the pavement, well apart from the main throng. ‘Gent over there–but the poor cove’s got it all backwards. That’s the doctor what saved him, stopped him breathing his last in Tamper’s Yard.’ The many hands bearing the major knocked him inadvertently against the side of the cart. He squealed in agony and released a further stream of profanities. The sergeant patted his arm. ‘Easy, there, easy!’

Impulsively, Jemima decided that she would meet this heroic doctor. He was propped against a lamppost at the corner of Bond Street, staring down at his hands. They were shining with water; he’d plainly just been washing them at the pump that stood nearby, to clean off the major’s blood. A rusty lantern stood at his side. As she approached, she realised that he was talking in a harsh, low voice, as if admonishing himself.

‘Excuse me, doctor,’ she began, feeling a little awkward. ‘Permit me to introduce myself. I am Mrs Jemima James.’ She hesitated. ‘I am told that your intervention prevented this man’s death. A noble act indeed.’

He looked up sharply, his face hard and lean in the gaslight. ‘It was not noble, madam,’ he replied. ‘And I am no doctor.’

Immediately, Jemima’s interest was roused–this man had just saved a life, and yet seemed not only angry but strangely ashamed. She smiled disbelievingly. ‘Surely you have medical experience of some kind, though? How else could you have treated the major over there with such skill and success?’

‘He is a major?’ The man’s tone was faintly hostile.

Jemima nodded, studying him. ‘So my brother tells me–from the 25th Manchesters. And he is in your debt.’

The man pulled himself upright. Jemima saw that his shirt and trousers were stiff with drying blood. ‘I did little enough, in truth. The major may die yet.’

He was silent for a moment, as if contemplating this bleak fact. Jemima noted that he had not denied her conjectures. She glanced at his boots, always the best indicator of wealth; they were inexpensive and a long way past their best. Perhaps he was once a medical student, she thought, obliged to abandon his studies due to lack of funds.

The man moved back from the edge of the pavement, smoothing his hair and straightening his ruined shirt. There was pleasing angularity to his features, interrupted only by deep crescents beneath the eyes, etched into the skin by want of rest. When he spoke again, his initial terseness was gone.

‘You must excuse my attire, Mrs James, and my manners. It has been a trying evening.’ He looked past her to the cart bearing the wounded officer, which was preparing to start up the street towards Piccadilly.

Jemima perceived that he was considering flight. ‘Tell me, sir,’ she said quickly, thinking to halt him, ‘if you are not a doctor, then what are you?’

‘I am a newspaperman.’ He made a shallow bow. ‘Thomas Kitson, madam. Of the Manchester Evening Star.’

Bill appeared breathlessly at Jemima’s side. He congratulated Mr Kitson for his efforts, shaking his damp hand before speculating briefly on the identity of the assailant. Then he informed Jemima that he was going up to his club to tell Freddie Keane and the rest of the chaps about the attack. Jemima tried to contain her irritation; this was typical of Bill. He would now stay out all night, roaming the very same streets he had been voicing such caution about ten minutes earlier–leaving her to endure their father alone. It had happened on countless previous occasions.

‘Mr Kitson,’ she said brightly, ‘would you do me the honour of taking some refreshment in my father’s office across the street? You must be in need of fortification after your labours, sir, noble or not. There is brandy, isn’t there, William?’

The deal had been proposed. Bill furrowed his brow, but he was not about to object. He nodded, mumbling an affirmative. Mr Kitson tried to protest, but was too tired and too courteous to disappoint her. After accepting Jemima’s invitation, he went to the cluster of working people close to the cart–not to check on the injured officer but to point out the location of the rusty lamp to a couple of workmen. It was most extraordinary. He seemed to be actively avoiding the man he had saved, as if he had some personal objection to him. Jemima could not account for it.

Bill walked Jemima and Mr Kitson back to the office, leaving them with the desk clerk. They sat before the window, Mr Kitson moving a chair next to the one Jemima had occupied earlier. The clerk, watching their bloodstained guest very closely, poured a tumbler of brandy and brought it over, setting it on the wide sill. Mr Kitson picked up the glass, hesitating when it was close to his lips. It was clear that he still found something about his hand profoundly distasteful. He had washed both quite thoroughly at the pump, but had evidently not managed to clean them to his satisfaction. Swallowing the liquor in one swift gulp, he put the glass back down and muttered an apology for his hastiness.

Jemima knew little of the Evening Star, but she felt that this man could not be a representative example of its staff. He had no real accent, for example–one would surely expect a correspondent from so modest a publication to be a Lancashire man from the lower middle classes, with the speech to match. I’d stake my library, she mused, on Mr Kitson being a recent arrival in our city. Adopting a cordial tone, she began to inquire politely about his situation.

He proved an agreeable if somewhat opaque conversationalist. He’d been in Manchester only since the end of the previous year, as she’d guessed. Other things about him, however, were more surprising.

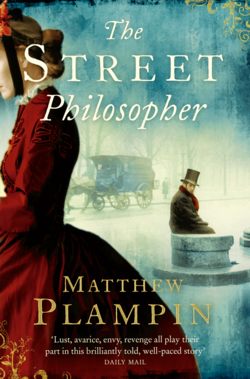

‘I am the Star’s society writer,’ he revealed. ‘A street philosopher, I believe it is called in these parts.’

‘A street philosopher?’ Jemima didn’t try to hide her amazement. ‘A professional gossip, you mean? The spy who lurks on the margins of our parks and theatres, labelling everyone who passes him with some acidic, facetious sobriquet? Surely not! I mean–you must excuse me, Mr Kitson, but you hardly seem the type.’ As a rule, Jemima tried to keep well clear of any publication that vaunted such writing as part of its appeal. It tended to be facile in the extreme, tawdry and vacuous, concerned only with fashion, scandal and money. And it was proving increasingly hard to avoid.

He appeared unperturbed by her reaction; there might even have been amusement in his eyes. ‘You flatter me with your doubt, Mrs James, but it takes more expertise than you might realise. There are important lessons to be learned, you know, from the living panorama of the modern city–lessons in the ever-shifting chances and changes of life.’ He turned his face away from the window as the major’s dray rolled past, a chattering crowd trailing behind it. ‘Besides, I was in urgent need of a position, and it was the only one available.’

Was this a mordant joke, or in earnest? Jemima found that she could not tell. ‘Are you working now, Mr Kitson? Can I expect to feature in the next edition of the Star?’

The smile was a brief one, and obviously infrequent. ‘No, madam, I’m afraid that I have other responsibilities at present. My paper has no dedicated art correspondent, you see, so they have assigned me to cover the Exhibition.’

This disclosure made Jemima immediately impatient. The Art Treasures Exhibition was widely held to be the finest undertaking ever to be staged in Manchester, the city’s answer to the Great Exhibition of 1851. A vast display had been gathered from the private picture collections of the country, and then assembled in a modish iron-and-glass structure at Old Trafford, on the outskirts of town–well away from the grime of the factories. Charles Norton, Jemima’s father, was on the ninety-strong committee of local luminaries who had brought this thing into existence, and she had been made to listen to his boasting and self-aggrandising on the subject for the better part of a year. The building was to be opened in three days’ time, with all the pomp and splendour that the rich men of the city could procure. The trip to town for new clothes had been Jemima’s final trial before the occasion itself.

‘The Exhibition,’ she intoned heavily, dragging the word out to its constituent syllables. ‘Do you concur with the general chorus of opinion, then, Mr Kitson, and believe that it will be a magnificent triumph?’

‘I do, Mrs James, very much so.’ He paused. ‘But you, I think, do not.’

Jemima sat up in her chair. ‘I simply look around me, sir,’ she responded with some energy, ‘at the slums of Salford, and Ancoats, and elsewhere, and then at the glorious Art Treasures Exhibition, and the many thousands of guineas that have vanished into it, and I cannot help but think that if the masters of the Cottonopolis were really interested in the benefit of all, as they so frequently say, they would realise that an art exhibition is a long way down the list of things that our urban poor require.’

‘I must say, madam,’ Mr Kitson murmured, ‘that for the daughter of a labour-lord, you are quite the radical.’

This was the first indication he had given that he knew who she was, and in whose premises he sat. ‘So I am told. Often by the labour-lord himself.’

He smiled again. Mr Kitson and I are forming quite an acquaintance, Jemima thought. She willed further delay upon her coach, thinking that she could happily sit exchanging views with this man for the rest of the evening. Something, at least, had been salvaged from a tiresome day. Across the room, the clerk cleared his throat loudly and turned over a page in his ledger.

The Star’s street philosopher began to offer his own opinions on the Exhibition. As he spoke, his ironic nuance fell away and was replaced with warm conviction, making Jemima feel frostily cynical by comparison. For him, the Exhibition was the first in a tradition, the harbinger of a new age: a popular art exhibition, staged for the country at large. Gone would be the days of art being solely an attribute of privilege. With this exemplar, he claimed, the exclusive galleries of old would have an egalitarian counterpoint, and the fruits of mankind’s finest endeavours would be available to all.

Jemima was familiar with this position, and frankly thought it a little idealistic; but had never heard it outlined with such eloquent sincerity. ‘You feel strongly on this subject, Mr Kitson,’ she observed. ‘One might reasonably infer that you had been forced to spend time in these exclusive galleries you so despise.’

This dispelled Mr Kitson’s enthusiasm completely. He stared down at the office’s elaborately tiled floor. ‘I was an art correspondent on a London paper before I came to Manchester,’ he admitted. ‘I attended countless exhibitions–every one closed to the broad mass of society.’

‘A London paper? Which one?’

Mr Kitson did not look up. ‘The Courier.’

Now Jemima was intrigued. This man had left one of Britain’s most prestigious journals, famous for the global scope of its correspondence, to write for the Manchester Evening Star, which was barely known even in the next county. ‘Why, I take the Courier myself! I have probably read your work, Mr Kitson. I shall have to search through my old issues as soon as I arrive home. May I ask why you left?’

He became evasive, volunteering only that he had become fatigued with life in the capital and the vagaries of the London art world. There was something in his manner that made Jemima realise that this man had fled to Manchester. But what could be so bad as to make one look for refuge in the nation’s workshop, writing street philosophy for a penny paper? There was an explanation here well beyond the fatigue that Mr Kitson claimed–although he was certainly a man on whom fatigue had preyed.

Jemima peered back into the room, at a row of framed prints on its far wall. ‘Do you know, I believe there are some illustrations from the Courier in this very office. From the Russian War–the opening stages of the campaign, before the paper’s coverage became so controversial, and—’

Mr Kitson sprung to his feet, startling Jemima and the desk clerk and almost knocking over his chair. He strode over to the prints and made a rapid survey of them, stopping before one that depicted the battlefield of the Alma.

‘Mrs James, why on earth does your father decorate his sales office with such images?’ The question was almost accusatory. He did not turn from the picture as he asked it; his earlier curtness had returned with his distraction.

Jemima remained quite calm. She directed a restraining glance at the clerk, who seemed ready to fetch a constable. ‘For all your familiarity with Manchester society, Mr Kitson, you street philosophers clearly know little of our city’s business affairs. Charles Norton’s meteoric rise is one of the great tales of the town. And the late war played a crucial role in it.’

She rose from her seat, arranged her shawl around her shoulders and crossed the office to stand beside him. His eyes shone as if filmed with tears; his face was impassive, though, and he was gripping one hand with the other to stop them from shaking. They looked at the Courier print, at the hillside strewn with the dead, and she told him how her father had found his fortune.

Two and a half years ago, at the start of 1855, Charles Norton had been the master of one of Manchester’s smallest foundries–the continuing survival of which was a source of some wonderment to the city’s community of businessmen. When he had been approached by William Fairbairn of the mighty Fairbairn shipbuilding and engineering company and asked if he would be willing to travel out to the Crimea to conduct a preliminary survey for a personal project of his, Charles had been in no position to refuse. The favour of the Fairbairns meant much in Manchester, and there was a clear implication that further work might result from this expedition. Whilst there, however, in a decidedly uncharacteristic demonstration of charm and initiative, Charles had befriended several remarkably senior figures in the Quartermaster-General’s department. The result of this surprising gregariousness was a sudden flow of contracts for the Norton Foundry.

‘First there were spikes for the Crimean railway; then heavy buckles for horse artillery; then more buckles, this time for the cavalry, many thousands of them; then, after the war, buckles for the police, for fire engines and coal carts, for cabs and coach-makers and hauliers of all descriptions. The Foundry has enjoyed a late flourishing, expanding to more than ten times its original size. Strong, affordable Norton buckles on every saddle, belt and harness in England–that is my father’s stated goal.’ Jemima smiled wryly. ‘Last year Punch christened him the Buckle King.’

Mr Kitson had managed to tear his attention from the print, and was suppressing his agitation by listening to her account with an absolute focus. ‘That I saw,’ he said.

Jemima’s smile faded. ‘Of course, a price was exacted for all this good fortune.’

The street philosopher looked at her inquiringly.

‘My husband, Mr Kitson–Anthony James. He died of cholera at Balaclava.’

Her companion flinched, the fine web of lines around his eyes tightening. ‘I am sorry, madam. I was aware that you had lost your husband, I confess, but I had no idea that…’ His voice trailed off. ‘Please accept my apologies.’

Jemima waved this away. ‘You were not to know, Mr Kitson. The circumstances of Anthony’s death are hardly common knowledge. And I have received enough apologies, sir, and enough pity, to last me several lifetimes. The truth is that my husband was quite determined to go, and would not hear otherwise. He was my father’s immediate subordinate at the Foundry, and considered his presence on the expedition vital to its success.’ Her voice quickened slightly. ‘There was a great fashion for it, do you not remember, amongst a certain type of gentleman. They rushed out to the Crimea with a boyish zeal, hungry for adventure, as if it was all nothing but larks.’

Mr Kitson said nothing.

Bridles jangled outside, followed by a coachman’s cry; a lantern flashed across the office window. The carriage had finally arrived from Norton Hall. The desk clerk, no doubt looking forward to solitude, darted out of the door and began berating the coachman for his tardiness. Their time together was fast expiring.

Jemima sighed, putting a hand to her brow. ‘Oh, do forgive me. I sound as if I am still mired in events well over two years past.’ She looked at him. ‘I have very much enjoyed our conversation this evening, Mr Kitson.’

He inclined his head. ‘As have I, Mrs James. My thanks again for the kind invitation.’

The clerk and coachman entered the office; the latter tipped his cap and then they began loading Jemima and Bill’s packages onto the carriage. Bill’s absence, being far from unusual, was not queried.

‘Will you be attending the opening ceremony on Tuesday, sir?’

‘I would be there, madam, even if my employer did not require it of me.’ His eyebrow raised a fraction. ‘I take it you will be going also, despite your reservations?’

‘Like yourself, Mr Kitson, I am obliged to attend, but on pain of disinheritance. What of the ball that evening, at the Fairbairn house–the Polygon? Will you be there as well?’

He hesitated, as if unable to remember. Jemima regretted having asked; it did seem improbable that a society writer from the Evening Star would be welcome at such a gathering.

‘No matter,’ she said lightly. ‘I shall look out for you in the Art Treasures Exhibition. Farewell, Mr Kitson.’

The carriage pulled away. Jemima settled back into her seat, watching Mr Kitson leave the office and cross Mosley Street. The stains on his shirt had dried to a muddy brown. He stopped on a corner and cast a last look at her carriage; then he stepped away into the shadows, hunching his shoulders against the evening’s chill.

Jemima’s mind teemed with questions about her enigmatic new acquaintance. What lay behind his attitude towards the man he had saved, his strange reticence about his time at the London Courier, and his extraordinary reaction to those prints? That this street philosopher bore a burden was plain to see, for all his sardonic detachment. The carriage left Mosley Street, rocking as it wheeled around across dung-caked cobbles of Piccadilly. Jemima looked out at the winding lines of gaslights and the people milling beneath, her thoughts turning to the bundle of old Couriers that she had packed away at the back of her wardrobe. She would find answers.