Читать книгу The Name of the Star - Maureen Johnson - Страница 12

5

ОглавлениеIFE AT WEXFORD BEGAN PROMPTLY AT SIX ON Monday morning, when Jazza’s alarm went off seconds before mine. This was followed by a pounding on the door. The pounding went down the hall, as every door was knocked.

“Quick,” Jazza said, springing out of bed with a speed that was both alarming and unacceptable at this hour.

“I can’t run in the morning,” I said, rubbing my eyes.

Jazza was already putting on her robe and picking up her towel and bath basket.

“Quick!” she said again. “Rory! Quick!”

“Quick what?”

“Just get up!”

Jazza rocked from foot to foot anxiously as I pulled myself out of bed, stretched, fumbled around filling my bath basket.

“So cold in the morning,” I said, reaching for my robe. And it really was. Our room must have dropped about ten degrees in temperature from the night before.

“Rory …”

“Coming,” I said. “Sorry.”

I require a lot of things in the morning. I have very thick, long hair that can be tamed only by the use of a small portable laboratory’s worth of products. In fact—and I am ashamed of this—one of my big fears about coming to England was having to find new hair products. That’s shameful, I know, but it took me years to come up with the system I’ve got. If I use my system, my hair looks like hair. Without my system, it goes horizontal, rising inch by inch as the humidity increases. It’s not even curly—it’s like it’s possessed. Obviously, I needed shower gel and a razor (shaving in the group shower—I hadn’t even thought about that yet) and facial cleanser. Then I needed my flip-flops so I didn’t get shower foot.

I could feel Jazza’s increasing sense of despair traveling up my spine, but I was hurrying. I wasn’t used to having to figure all these things out and carry all my stuff at six in the morning. Finally, I had everything necessary and we trundled down the hall. At first, I wondered what the fuss was about. All the doors along the hall were closed, and there was little noise. Then we got to the bathroom and opened the door.

“Oh, no,” she said.

And then I understood. The bathroom was completely packed. Everyone from the hall was already in there. Each shower stall was already taken, and three or four people were lined up by each one.

“You have to hurry,” Jazza said. “Or this happens.”

It turns out there is nothing more annoying than waiting around for other people to shower. You resent every second they spend in there. You analyze how long they are taking and speculate on what they are doing. The people in my hall showered, on average, ten minutes each, which meant that it was over a half hour before I got in. I was so full of indignation about how slow they were that I had already preplanned my every shower move. It still took me ten minutes, and I was one of the last ones out of the bathroom.

Jazza was already in our room and dressed when I stumbled back in, my hair still soaked.

“How soon can you be ready?” she asked as she pulled on her school shoes. These were by far the worst part of the uniform. They were rubbery and black, with thick, nonskid soles. My grandmother wouldn’t have worn them. But then, my grandmother was Miss Bénouville 1963 and 1964, a title largely awarded to the fanciest person who entered. In Bénouville in 1963 and 1964, the definition of fancy was highly questionable. I’m just saying, my grandmother wears heeled slippers and silk pajamas. In fact, she’d bought me some silk pajamas to bring to school. They were vaguely transparent. I’d left them at home.

I was going to tell Jazza all of this, but I could see she was not in the mood for a story. So I looked at the clock. Breakfast was in twenty minutes.

“Twenty minutes,” I said. “Easy.”

I don’t know what happened, but getting ready was just a lot more complicated than I thought it would be. I had to get all the parts of my uniform on. I had trouble with my tie. I tried to put on some makeup, but there wasn’t a lot of light by the mirror. Then I had to guess which books I had to bring for my first classes, something I probably should have done the night before.

Long story short, we left at 7:13. Jazza spent the entire wait sitting on her bed, eyes growing increasingly wide and sad. But she didn’t just leave me, and she never complained.

The refectory was packed, and loud. The bonus of being so late was that most people had gone through the food line. We were up there with the few guys who were going back for seconds. I grabbed a cup of coffee first thing and poured myself an impossibly small glass of lukewarm juice. Jazza took a sensible selection of yogurt, fruit, and whole-grain bread. I was in no mood for that kind of nonsense this morning. I helped myself to a chocolate doughnut and a sausage.

“First day,” I explained to Jazza when she stared at my plate.

It became clear that it was going to be tricky to find a seat. We found two at the very end of one of the long tables. For some reason, I looked around for Jerome. He was at the far end of the next table over, deep in conversation with some girls from the first floor of Hawthorne. I turned to my plate of fats. I realized how American this made me seem, but I didn’t particularly care. I had just enough time to stuff some food down my throat before Mount Everest stood up at his dais and told us that it was time to move along. Suddenly, everyone was moving, shoving last bits of toast and final gulps of juice into their mouths.

“Good luck today,” Jazza said, getting up. “See you at dinner.”

The day was ridiculous.

In fact, the situation was so serious I thought they had to be joking—like maybe they staged a special first day just to psych people out. I had one class in the morning, the mysteriously named “Further Maths.” It was two hours long and so deeply frightening that I think I went into a trance. Then I had two free periods, which I had laughingly dismissed when I first saw them. I spent them feverishly trying to do the problem sets.

At a quarter to three, I had to run back to my room and change into shorts, sweatpants, a T-shirt, a fleece, and these shin pads and spiked shoes that Claudia had given to me. From there, I had to get three streets over to the field we shared with a local university. If cobblestones are a tricky walk in flip-flops, they are your worst nightmare in spiked shoes and with big, weird pads on your shins. I arrived to find that people (all girls) were (wisely) putting on their spiked shoes and pads there, and that everyone was wearing only shorts and T-shirts. Off came the sweatpants and fleece. Back on with the weird pads and spikes.

Charlotte, I was dismayed to find, was in hockey as well. So was my neighbor Eloise. She lived across the hall from us in the only single. She had a jet-black pixie cut and a carefully covered arm of tattoos. She had a huge air purifier in her room, which had gotten some kind of special clearance (since we couldn’t have appliances). Somehow she got a doctor to say she had terrible allergies, hence she would need the purifier and her own space. In reality, she used the filter to hide the fact that she spent most of her free time smoking cigarette after cigarette and blowing smoke directly into the purifier. Eloise spoke fluent French because she lived there a few months out of every year. As for the smoking, she never actually said, “It’s a French thing,” but it was implied. Eloise looked as dismayed as I did about the hockey. The rest looked grimly determined.

Most people had their own hockey sticks, but for those of us who didn’t, they were distributed. Then we stood in line, where I shivered.

“Welcome to hockey!” Claudia boomed. “Most of you have played hockey before—we’re just going to run through some basics and drills to get back into things.”

It became pretty obvious pretty quickly that “most of you have played hockey before” actually meant “every single one of you except for Rory has played hockey before.” No one but me needed the primer on how to hold the stick, which side of the stick to hit the ball with (the flat one, not the roundy one). No one needed to be shown how to run with the stick or how to hit the ball. The total amount of time given to these topics was five minutes. Claudia gave us all a once-over to make sure we were properly dressed and had everything we needed. She stopped at me.

“Mouth guard, Aurora?”

Mouth guard. Some lump of plastic she had left by my door during the morning. I’d forgotten it.

“Tomorrow,” she said. “For now, you’ll just watch.”

So I sat on the grass on the side of the field while everyone else put their plastic lumps in their mouths, turning the space previously full of teeth into alarming leers of bright pink and neon blue. They ran up and down the field, passing the ball back and forth to each other. Claudia paced alongside the entire time, barking commands I didn’t understand. The process of hitting the ball looked straightforward enough from where I was, but these things never are.

“Tomorrow,” she said to me when the period was over and everyone left the field. “Mouth guard. And I think we’ll start you in goal.”

Goal sounded like a special job. I didn’t want a special job, unless that special job involved sitting on the side under a pile of blankets.

Then we all ran back to Hawthorne—and I mean ran, literally—where everyone was once again competing for the showers. I found Jazza back in our room, dry and dressed. Apparently, there were showers at the pool.

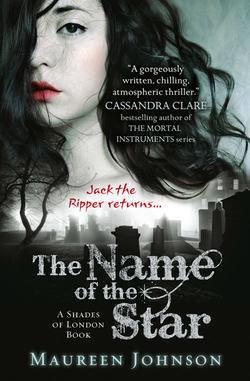

Dinner featured some baked potatoes, some soup, and something called a “hot pot,” which looked like beef and potatoes, so I took that. Our groupings were becoming more predictable, and I was starting to understand the dynamic. Jerome, Andrew, Charlotte, and Jazza had all been friends last year. Three of them had become prefects; Jazza had not. Jazza and Charlotte didn’t get along. I attempted to join in the conversations, but found I didn’t have much to share until the topic came around to the Ripper, when I dove in with a little family history.

“People love murderers,” I said. “My cousin Diane used to date a guy on death row in Texas. Well, I don’t know if they were dating, but she used to write him letters all the time, and she said they were in love and going to get married. But it turns out he had, like, six girlfriends, so they broke up and she opened her Healing Angel Ministry …”

I had them now. They had all slowed their eating and were looking over.

“See,” I said, “Cousin Diane runs the Healing Angel Ministry out of her living room. Well, and also her backyard. She has a hundred sixty-one statues of angels in her backyard. Plus she has eight hundred seventy-five angel figurines, dolls, and pictures in the house. And people go to her for angel counseling.”

“Angel counseling?” Jazza repeated.

“Yep. She plays New Age music and has you close your eyes, and then she channels some angels. She tells you their names and what colors their auras are and what they’re trying to tell you.”

“Is your cousin … insane?” Jerome asked.

“I don’t think she’s insane,” I said, digging into my hot pot. “This one time, I was over at her house. When I get bored there, I channel angels, so she feels like she’s doing a good job. I go like this …”

I took a big, deep breath to prepare for my angel voice. Unfortunately, I did so while taking a bite of the hot pot. A chunk of beef slipped down my throat. I felt it stop somewhere just under my chin. I tried to clear my throat, but nothing happened. I tried to cough. Nothing. I tried to speak. Nothing.

Everyone was watching me. Maybe they thought this was part of the imitation. I pushed away from the table a bit and tried to cough harder, then harder still, but my efforts made no difference. My throat was stopped. My eyes watered so much that everything went all runny. I felt a rush of adrenaline … then everything went white for a second, completely, totally, brilliantly white. The entire refectory vanished and was replaced by this endless, paperlike vista. I could still feel and hear, but I seemed to be somewhere else, somewhere without air, somewhere where everything was made of light. Even when I closed my eyes, it was there. Someone was yelling that I was choking, but the words sounded like they were far away.

And then arms were around my middle. There was a fist jabbing into the soft tissue under my rib cage. I was jerked up, over and over, until I felt a movement. The refectory dropped back into place as the beef launched itself out of me and flew off in the direction of the setting sun and a rush of air came into my lungs.

“Are you all right?” someone said. “Can you speak? Try to speak.”

“I…”

I could speak, and that was all I felt like saying at the moment. I fell against the bench and put my head on the table. There was a pounding of blood in my ears. I looked deep into the markings of the wood and examined the silverware up close. My face was wet with tears I didn’t remember crying. The refectory had gone totally silent. At least, I think it was silent. My heart was drumming in my ears so loudly that it drowned out anything else. Someone was telling people to move back and give me air. Someone else was helping me up. Then some teacher (I think it was a teacher) was in front of me, and Charlotte was there as well, poking her big red head into the frame.

“I’m fine,” I said hoarsely. I wasn’t fine. I just wanted to leave, to go somewhere and cry. I heard the teacher person say, “Charlotte, take her to the san.” Charlotte attached herself to my right arm. Jazza attached herself to my left.

“I’ve got her,” Charlotte said crisply. “You can continue eating.”

“I’m coming,” Jazza shot back.

“I can walk,” I croaked.

Neither one of them loosened their grip, which was probably for the best, because it turned out my ankles and knees had gone all rubbery. They escorted me down the center aisle, between the long benches, as people turned and watched me go. Considering that the refectory was an old church, our exit probably looked like the end of a very unusual wedding ceremony—me being dragged down the aisle by my two brides.