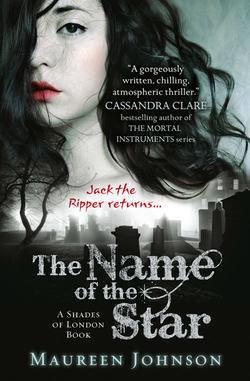

Читать книгу The Name of the Star - Maureen Johnson - Страница 14

7

ОглавлениеNEXT DAY, IT RAINED.

I began the day with double French. At home, French was one of my strongest subjects. Louisiana has French roots. Lots of things in New Orleans have French names. I thought French was going to be my best subject, but this illusion was quickly shattered when our teacher, Madame Loos, came in rattling off French like an annoyed Parisian. I went right from there to double English Literature, where we were informed that we would be working on the period from 1711 to 1847. What alarmed me about that was its specificity. I didn’t even think it was that the material was necessarily much harder than what I had in school at home—it was more that they were so adult about it. The teachers spoke with a calm assurance, like we were all fully qualified academics, and everyone acted accordingly. We would be reading Pope, Swift, Johnson, Pepys, Fielding, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Richardson, Austen, the Brontës, Dickens … the list went on and on.

Then I had lunch. It continued to rain.

After lunch I had a free period, which I spent having a panic attack in my room.

I thought for sure that they would cancel hockey. In fact, I asked someone what we did when our sports hour was canceled because of the weather, and she just laughed. So it was off to the field in my tiny shorts and fleece, with my mouth guard, of course. The night before I had to put it in a mug of boiling water to make it soft and mold it to my teeth. That was a pleasant feeling. At the field, I was greeted with the goal-keeper equipment. I’m not sure who designed the field hockey goalie’s uniform, but I’d guess it was someone who decided to merge his or her love of safety with a truly macabre sense of humor. There were swollen blue pads for my shins that were easily twice the width of my leg. There was another set for the upper thigh. The arm pads were like massively overinflated floaties. There were chest pads with an oversized jersey to go over them and huge, cartoonish shoe objects for my feet. Then there was a helmet with a face guard. The overall effect was like one of those bodysuits you can get to make you look like a sumo wrestler—but far less elegant and human. It took me fifteen minutes to get all this stuff on, and then I had to figure out how to walk in it. The other goalie, a girl named Philippa, got hers on in half the time and was running, wide-legged, onto the field while I was still trying to get the shoes on.

Once I did that, my job was to stand in the goal while people hit hockey balls at me. Claudia kept yelling at me to repel this onslaught using my feet, but sometimes she would tell me to use my arms. All the while, rain poured onto the helmet and streamed down my face. I couldn’t move, so the balls just hit me. When it was all over, Charlotte came up to me as I was trying to get out of the padding.

“If you want some help,” she said, “I’ve been playing for a long time. I’d be happy to run drills with you.”

What was especially painful about this was that I think she meant it.

At home, I had the third-highest GPA in my class, and literature was my thing. I would do the reading for English first. The essay I had to read was called “An Essay on Criticism” by Alexander Pope.

The first challenge was that the essay was, in fact, a very long poem in “heroic couplets.” If something is called an essay, it should be an essay. I read it twice. A few lines stood out, like “For fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” Now I knew where that came from. But I still didn’t really know what it was about. I looked online first, but I quickly realized I had to up my game a little here at Wexford. This was a place for some book learning. So I went to the library.

Our school library at home was an aluminum bunker thing that they had attached to the school. It had no windows and an air conditioner that whistled. The Wexford library was a proper library. The floor was made of black-and-white stone. There were two levels of stacks—big, wooden ones. Then there was a massive work area, full of long wooden tables that had dividing walls, so you could have your own little space to sit in, with a shelf, a light, and plugs for your computer. The wall in front of you was even covered in cork and had pins, so you could tack up notes as you worked. This part was very modern and shiny, and it made me feel like a real person to sit there and work, like I really was one of these academics of Wexford. I could pretend, at least, and if I pretended long enough, maybe I could make it into a reality.

I took a seat at one of the empty cubicles and spent several minutes setting it up. I plugged in my computer. I pinned my course syllabus to the cork wall and stared it down. Everyone else in this room was calmly carrying on. No one had, to my knowledge, read their course assignments and tried to escape through a chimney. I had been admitted to Wexford, and I had to assume that they didn’t do that just to be funny.

Wexford had a large assortment of books on Alexander Pope, so I headed off to the Literature Ol–Pr section, which was on the upper level and in the back. When I got to the aisle, I found a guy lounging right in the middle of it, on the floor, reading. He was in his uniform, but wore an oversized trench coat on top of it. He had really elaborate, bleached-blond, sticky-uppy hair formed into spikes. And he was singing a song.

Panic on the streets of London,

Panic on the streets of Birmingham …

Sure, it was very romantic to lounge around in the literature section with big hair, but he was doing this in the dark. All the aisles had lights on timers. When you went into the aisle, you turned on the light. It clicked itself off after ten minutes or so. He hadn’t bothered to do this and was reading with just the scant amount of light coming from the window at the far end of the aisle. He didn’t move or look up, even when I had to stand right next to him and reach over him to get to the books. There were about ten books of collected works of Alexander Pope, which I didn’t need. I had the poem—I needed something to tell me what the hell it meant. Next to those were several books about Alexander Pope, but I had no idea which one I wanted. They were also very large. Meanwhile, the guy kept singing.

I wonder to myself,

Could life ever be sane again?

“Excuse me. Could I ask you to move a little?” I said.

He looked up slowly and blinked.

“Are you talking to me?”

There was a dim confusion in his eyes. He tucked in his knees and spun around on his butt so that he was facing up at me. Now I understood what people meant by bluebloods—he was the palest person I had ever seen, a genuine grayish-blue in the light of the aisle.

“What are you singing?” I asked. I hoped he would take that as “please stop singing.”

“It’s called ‘Panic,’” he said. “It’s by the Smiths. There’s panic on the streets now, isn’t there? Ripper and all that. Morrissey’s a prophet.”

“Oh,” I said.

“What are you looking for?”

“A book on Alexander Pope, and I—”

“For what?”

“I have to read ‘An Essay on Criticism.’ I read it, I just don’t … I need a book about it. A criticism book.”

“Then you don’t want these,” he said, standing up. “They’re all rubbish. You’ll do far better with something that puts Pope’s work into context. See, Pope was talking about the importance of good criticism. All those books are just biographies with some padding. You want the general criticism section, which is over here.”

It seemed to take extraordinary effort for him to stand up. He pulled his coat tight and shied away from me a little. Then he gave a little jerk of his spiky head to indicate that I should follow him, which I did. He maneuvered around the gloomy stacks, turning abruptly a few aisles down. He didn’t turn on the light when we went in—I had to switch it on. He also didn’t need to scan for the section or book he was looking for. He walked right to it and pointed to the red spine.

“This one. By Carter. This one talks about Pope’s role in shaping the modern critic. And this one”—he indicated a green book two shelves down—“by Dillard. A little basic, but if you’re new to criticism, worth a read.”

I decided not to be resentful of the fact that he assumed I was “new to criticism.”

“You’re American,” he said, leaning against the shelf behind us. “We don’t normally get Americans.”

“Well, you got me.”

I wasn’t sure what to do next. He wasn’t talking; he was just staring at me as I held the book. So I flipped it open and started looking at the contents. There was an entire chapter on “An Essay on Criticism.” It was twenty pages long. I could read twenty pages if it helped me look less clueless.

“I’m Rory,” I said.

“Alistair.”

“Thanks,” I said, holding up the book.

He didn’t reply. He just sat down on the floor and folded his trench-coated arms and stared up at me.

The aisle light clicked off as I left, but he didn’t move.

It was going to take some time before I understood Wexford and its ways.