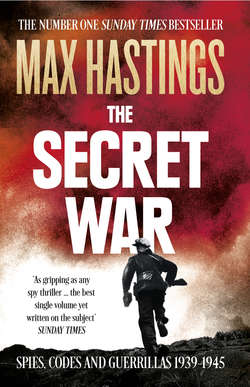

Читать книгу The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939–1945 - Max Hastings, Sir Max Hastings, Max Hastings - Страница 6

Introduction

ОглавлениеThis is a book about some of the most fascinating people who participated in the Second World War. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, civilians had vastly diverse experiences, forged by fire, geography, economics and ideology. Those who killed each other were the most conspicuous, but in many ways the least interesting: outcomes were also profoundly influenced by a host of men and women who never fired a shot. While even in Russia months could elapse between big battles, all the participants waged an unceasing secret war – a struggle for knowledge of the enemy to empower their armies, navies and air forces, through espionage and codebreaking. Lt. Gen. Albert Praun, the Wehrmacht’s last signals chief, wrote afterwards of the latter: ‘All aspects of this modern “cold war of the air waves” were carried on constantly even when the guns were silent.’ The Allies also launched guerrilla and terrorist campaigns wherever in Axis-occupied territories they had means to do so: covert operations assumed an unprecedented importance.

This book does not aspire to be a comprehensive narrative, which would fill countless volumes. It is instead a study of both sides’ secret war machines and some of the characters who influenced them. It is unlikely that any more game-changing revelations will be forthcoming, save possibly from Soviet archives currently locked by Vladimir Putin. The Japanese destroyed most of their intelligence files in 1945, and what survives remains inaccessible in Tokyo, but veterans provided significant post-war testimony – a decade ago, I interviewed some of them myself.

Most books about wartime intelligence focus on the doings of a chosen nation. I have instead attempted to explore it in a global context. Some episodes in my narrative are bound to be familiar to specialists, but a new perspective seems possible by placing them on a broad canvas. Though spies and codebreakers have generated a vast literature, readers may be as astonished by some of the tales in this book as I have been on discovering them for myself. I have written extensively about the Russians, because their doings are much less familiar to Western readers than are those of Britain’s Bletchley Park, America’s Arlington Hall and Op-20-G. I have omitted many legends, and made no attempt to retell the most familiar tales of Resistance in Western Europe, nor of the Abwehr’s agents in Britain and America, who were swiftly imprisoned or ‘turned’ for the famous Double Cross system. By contrast, though the facts of Richard Sorge’s and ‘Cicero’s’* doings have been known for many decades, their significance deserves a rethink.

The achievements of some secret warriors were as breathtaking as the blunders of others. As I recount here, the British several times allowed sensitive material to be captured which could have been fatal to the Ultra secret. Meanwhile, spy writers dwell obsessively on the treachery of Britain’s Cambridge Five, but relatively few recognise what we might call the Washington and Berkeley five hundred – a small army of American leftists who served as informants for Soviet intelligence. The egregious Senator Joseph McCarthy stigmatised many individuals unjustly, but he was not wrong in charging that between the 1930s and 1950s the US government and the nation’s greatest institutions and corporations harboured an astonishing number of employees whose first loyalty was not to their own flag. True, between 1941 and 1945 the Russians were supposedly allies of Britain and the United States, but Stalin viewed this relationship with unremitting cynicism – as a merely temporary association, for the narrow purpose of destroying the Nazis, with nations that remained the Soviet Union’s historic foes and rivals.

Many books about wartime intelligence focus on what spies or codebreakers found out. The only question that matters, however, is how far secret knowledge changed outcomes. The scale of Soviet espionage dwarfed that of every other belligerent, and yielded a rich technological harvest from Britain and the United States, but Stalin’s paranoia crippled exploitation of his crop of other people’s political and military secrets. The most distinguished American historian of wartime codebreaking told me in 2014 that after half a lifetime studying the subject he has decided that Allied intelligence contributed almost nothing to winning the war. This seems too extreme a verdict, but my friend’s remarks show how scepticism, and indeed cynicism, breed and multiply in the course of decades wading in the morass of fantasy, treachery and incompetence wherein most spymasters and their servants have their being. The record suggests that official secrecy does more to protect intelligence agencies from domestic accountability for their own follies than to shield them from enemy penetration. Of what use was it – for instance – to conceal from the British public even the identities of their own spy chiefs, when for years MI6’s* most secret operations were betrayed to the Russians by Kim Philby, one of its most senior officers? The US government repudiated a bilateral intelligence exchange agreed with the NKVD* by Maj. Gen. William Donovan of OSS, but official caution did little for national security when some of Donovan’s top subordinates were passing secrets to Soviet agents.

Intelligence-gathering is not a science. There are no certainties, even when some of the enemy’s correspondence is being read. There is a cacophony of ‘noise’, from which ‘signals’ – truths large and small – must be extracted. In August 1939, on the eve of the Nazi–Soviet Pact, a British official wrung his hands over the confused messages reaching the Foreign Office about relations between Berlin and Moscow: ‘We find ourselves,’ he wrote – using words that may be applied to most intelligence – ‘when attempting to assess the value of these secret reports, somewhat in the position of the Captain of the Forty Thieves when, having put a chalk mark on Ali Baba’s door, he found that Morgana had put similar marks on all the doors in the street and had no indication which was the true one.’

It is fruitless to study any nation’s successes, its pearls of revelation, in isolation. These must be viewed in the context of hundreds of thousands of pages of trivia or outright nonsense that crossed the desks of analysts, statesmen, commanders. ‘Diplomats and intelligence agents, in my experience, are even bigger liars than journalists,’ wrote the British wartime spy Malcolm Muggeridge, who was familiar with all three, and something of a charlatan himself. The sterility of much espionage was nicely illustrated by František Moravec of Czech intelligence. One day in 1936 he proudly presented his commanding officer with a report on a new piece of German military equipment, for which he had paid an informant handsomely. The general skimmed it, then said, ‘I will show you something better.’ He tossed across his desk a copy of the magazine Die Wehrmacht, pointed out an article on the same weapon, and said dryly, ‘The subscription is only twenty crowns.’

In the same category fell the Abwehr transcript of a December 1944 US State Department message appointing a new economic affairs counsellor to the Polish exile government in London. This read, in part: ‘His transportation expenses and per diem, Tunis to London, via Washington, DC, transportation expenses and per diem for his family and shipment effects direct authorised, subject Travel Regulations.’ A page-long translation of this decrypt was stamped ‘Top Secret’ by its German readers. The man-hours expended by the Nazi war machine to secure this gem reflect the fashion in which intelligence services often move mountains to give birth to mice.

Trust is a bond and privilege of free societies. Yet credulity and respect for privacy are fatal flaws to analysts and agent-runners. Their work requires them to persuade citizens of other countries to abandon the traditional ideal of patriotism, whether for cash, out of conviction, or occasionally because of a personal bond between handler and informant. It will always be disputed territory, whether those who betray their society’s secrets are courageous and principled heroes who identify a higher loyalty, as modern Germans perceive the anti-Hitler Resistance, or instead traitors, as most of us classify Kim Philby, Alger Hiss – and in our own times Edward Snowden. The day job of many intelligence officers is to promote treachery, which helps to explain why the trade attracts so many weird people. Malcolm Muggeridge asserted disdainfully that it ‘necessarily involves such cheating, lying and betraying, that it has a deleterious effect on the character. I never met anyone professionally engaged in it whom I should care to trust in any capacity.’

Stalin said: ‘A spy should be like the devil; no one can trust him, not even himself.’ The growth of new ideologies, most significantly communism, caused some people to embrace loyalties that crossed frontiers and, in the eyes of zealots, transcended mere patriotism. More than a few felt exalted by discovering virtue in treason, though others preferred to betray for cash. Many wartime spymasters were uncertain which side their agents were really serving, and in some cases bewilderment persists to this day. The British petty crook Eddie Chapman, ‘Agent ZigZag’, had extraordinary war experiences as the plaything of British and German intelligence. At different times he put himself at the mercy of both, but it seems unlikely that his activities did much good to either, serving only to keep Chapman himself in girls and shoe leather. He was an intriguing but unimportant figure, one among countless loose cannon on the secret battlefield. More interesting, and scarcely known to the public, is the case of Ronald Seth, an SOE agent captured by the Germans and trained by them to serve as a ‘double’ in Britain. I shall describe below the puzzlement of SOE, MI5, MI6, MI9 and the Abwehr about whose side Seth ended up on.

Intelligence-gathering is inherently wasteful. I am struck by the number of secret service officers of all nationalities whose only achievement in foreign postings was to stay alive, at hefty cost to their employers, while collecting information of which not a smidgeon assisted the war effort. Perhaps one-thousandth of 1 per cent of material garnered from secret sources by all the belligerents in World War II contributed to changing battlefield outcomes. Yet that fraction was of such value that warlords grudged not a life nor a pound, rouble, dollar, Reichsmark expended in securing it. Intelligence has always influenced wars, but until the twentieth century commanders could discover their enemies’ motions only through spies and direct observation – counting men, ships, guns. Then came wireless communication, which created rolling new intelligence corn prairies that grew exponentially after 1930, as technology advanced. ‘There has never been anything comparable in any other period of history to the impact of radio,’ wrote the great British scientific intelligence officer Dr R.V. Jones. ‘… It was the product of some of the most imaginative developments that have ever occurred in physics, and it was as near magic as anyone could conceive.’ Not only could millions of citizens build their own sets at home, as did also many spies abroad, but in Berlin, London, Washington, Moscow, Tokyo electronic eavesdroppers were empowered to probe the deployments and sometimes the intentions of an enemy without benefit of telescopes, frigates or agents.

One of the themes in this book is that the signals intelligence war, certainly in its early stages, was less lopsided in the Allies’ favour than popular mythology suggests. The Germans used secret knowledge well to plan the 1940 invasion of France and the Low Countries. At least until mid-1942, and even in some degree thereafter, they read important Allied codes both on land and at sea, with significant consequences for both the Battle of the Atlantic and the North African campaign. They were able to exploit feeble Red Army wireless security during the first year of Operation ‘Barbarossa’. From late 1942 onwards, however, Hitler’s codebreakers lagged ever further behind their Allied counterparts. The Abwehr’s attempts at espionage abroad were pitiful.

The Japanese government and army high command planned their initial 1941–42 assaults on Pearl Harbor and the European empires of South-East Asia most efficiently, but thereafter treated intelligence with disdain, and waged war in a fog of ignorance about their enemies’ doings. The Italian intelligence service and its codebreakers had some notable successes in the early war years, but by 1942 Mussolini’s commanders were reduced to using Russian PoWs to do their eavesdropping on Soviet wireless traffic. Relatively little effort was expended by any nation on probing Italy’s secrets, because its military capability shrank so rapidly. ‘Our picture of the Italian air force was incomplete and our knowledge far from sound,’ admitted RAF intelligence officer Group-Captain Harry Humphreys about the Mediterranean theatre, before adding smugly, ‘So – fortunately – was the Italian air force.’

The first requirement for successful use of secret data is that commanders should be willing to analyse it honestly. Herbert Meyer, a veteran of Washington’s National Intelligence Council, defined his business as the presentation of ‘organized information’; he argued that ideally intelligence departments should provide a service for commanders resembling that of ship and aircraft navigation systems. Donald McLachlan, a British naval practitioner, observed: ‘Intelligence has much in common with scholarship, and the standards which are demanded in scholarship are those which should be applied to intelligence.’ After the war, the surviving German commanders blamed all their intelligence failures on Hitler’s refusal to countenance objective assessment of evidence. Signals supremo Albert Praun said: ‘Unfortunately … throughout the war Hitler … showed a lack of confidence in communications intelligence, especially if the reports were unfavourable [to his own views].’

Good news for the Axis cause – for instance, interceptions revealing heavy Allied losses – were given the highest priority for transmission to Berlin, because the Führer welcomed them. Meanwhile bad tidings received short shrift. Before the June 1941 invasion of Russia, Gen. Georg Thomas of the WiRuAmt – the Wehrmacht’s economics department – produced estimates of Soviet weapons production which approached the reality, though still short of it, and argued that the loss of European Russia would not necessarily precipitate the collapse of Stalin’s industrial base. Hitler dismissed Thomas’s numbers out of hand, because he could not reconcile their magnitude with his contempt for all things Slavonic. Field-Marshal Wilhelm Keitel eventually instructed the WiRuAmt to stop submitting intelligence that might upset the Führer.

The war effort of the Western democracies profited immensely from the relative openness of their societies and governance. Churchill sometimes indulged spasms of anger towards those around him who voiced unwelcome views, but a remarkably open debate was sustained in the Allied corridors of power, including most military headquarters. Gen. Sir Bernard Montgomery was a considerable tyrant, but those whom he trusted – including his intelligence chief Brigadier Bill Williams, a peacetime Oxford don – could speak their minds. All the United States’s brilliant intelligence successes were gained through codebreaking, and were exploited most dramatically in the Pacific naval war. American ground commanders seldom showed much interest in using their knowledge to promote deceptions, as did the British. D-Day in 1944 was the only operation for which the Americans cooperated wholeheartedly on a deception plan. Even then the British were prime movers, while the Americans merely acquiesced – for instance, by allowing Gen. George Patton to masquerade as commander of the fictitious American First US Army Group supposedly destined to land in the Pas de Calais. Some senior Americans were suspicious of the British enthusiasm for misleading the enemy, which they regarded as reflecting their ally’s enthusiasm for employing guile to escape hard fighting, the real business of war.

GC&CS, the so-called Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park, was of course not merely the most important intelligence hub of the conflict, but from 1942 Britain’s outstanding contribution to victory. Folk legend holds that Alan Turing’s creation of electro-mechanical bombes exposed Germany’s entire communications system to Allied eyes by breaking the Enigma’s traffic. The truth is far more complex. The Germans employed dozens of different keys, many of which were read only intermittently, often out of ‘real time’ – meaning insufficiently rapidly to make possible an operational response – and a few not at all. The British accessed some immensely valuable Enigma material, but coverage was never remotely comprehensive, and was especially weak on army traffic. Moreover, an ever-increasing volume of the Germans’ most secret signals was transmitted through a teleprinter network which employed an entirely different encryption system from that used by Enigma. The achievement of Bletchley’s mathematicians and linguists in cracking the Lorenz Schlüsselzusatz was quite distinct from, and more difficult than, breaking the Enigma, even though recipients in the field knew the products of all such activities simply as ‘Ultra’.* Bill Tutte, the young Cambridge mathematician who made the critical initial discoveries, is scarcely known to posterity, yet deserves to be almost as celebrated as Turing.

Ultra enabled the Allied leadership to plan its campaigns and operations in the second half of the war with a confidence vouchsafed to no previous warlords in history. Knowing the enemy’s hand did not diminish its strength, however. In 1941 and into 1942, again and again the British learned where the Axis intended to strike – as in Crete, North Africa and Malaya – but this did not save them from losing the subsequent battles. Hard power, whether on land or at sea or in the air, was indispensable to the exploitation of secret knowledge. So, too, was wisdom on the part of British and American commanders and their staffs – which proved conspicuously lacking at key moments during the 1944–45 north-west Europe campaign. Intelligence did, however, contribute importantly to mitigating some early disasters: young R.V. Jones’s achievement in showing the path towards jamming the Luftwaffe’s navigational beams significantly diminished the pain inflicted by the Blitz on Britain. At sea, Ultra’s pinpointing of German U-boats – with an alarming nine-month interruption in 1942 – made it possible to reroute convoys to evade them, an even more important contribution to holding open the Atlantic supply line than sinking enemy submarines.

The Americans had some reason to suspect their allies of romanticism about deception. Col. Dudley Clarke – famous not least to Spanish police, who once arrested him wearing woman’s clothes in a Madrid street – conducted a massive cover operation in the North African desert before the October 1942 Battle of El Alamein. Historians have celebrated Clarke’s ingenuity in creating fictional forces which caused Rommel to deploy significant strength well south of the focal point of Montgomery’s assault. However, such guile did not spare Eighth Army from the fortnight of hard fighting that proved necessary to break through the Afrika Korps. The Germans argued that Clarke’s activities changed nothing in the end, because they had time to redeploy northwards before the decisive British assault. In Burma Col. Peter Fleming, brother of the creator of James Bond, went to elaborate and hazardous lengths to leave a haversack full of deceptive ‘secret papers’ in a wrecked jeep where the enemy were bound to find it, but the Japanese took no notice of this haul when they got it. From 1942 onwards, British intelligence achieved an almost complete understanding of Germany’s air defences and the electronic technologies they employed, but Allied bomber forces continued to suffer punitive casualties, especially before US long-range fighters wrecked the Luftwaffe in the air in the spring of 1944.

Whatever the contribution of British tactical deceptions in North Africa, Allied deceivers had two important and almost indisputable strategic successes. In 1943–44, Operation ‘Zeppelin’ created a fictitious British army in Egypt which induced Hitler to maintain large forces in Yugoslavia and Greece to repel an Allied Balkan landing. It was this imaginary threat, not Tito’s guerrillas, that caused twenty-two Axis divisions to kick their heels in the south-east until after D-Day. The second achievement was, of course, that of Operation ‘Fortitude’ before and after the assault on Normandy. It bears emphasis that neither could have exercised such influence had not the Allies possessed sufficient hard power, together with command of the sea, to make it credible that they might land armies almost anywhere.

Some Russian deceptions dwarf those of the British and Americans. The story of agent ‘Max’, and the vast operation launched as a diversion from the Stalingrad offensive, at a cost of 70,000 Russian lives, is one of the most astonishing of the war, and almost unknown to Western readers. In 1943–44, other Soviet ruses prompted the Germans repeatedly to concentrate their forces in the wrong places in advance of onslaughts by the Red Army. Air superiority was an essential prerequisite, in the East as in the West: the ambitious deceptions of the later war years were possible only because the Germans could not carry out photographic reconnaissance to disprove the ‘legends’ they were sold across the airwaves and through false documents.

The Western Allies were much less successful in gathering humint than sigint.* Neither the British nor the Americans acquired a single highly placed source around the German, Japanese or Italian governments or high commands, until in 1943 OSS’s Allen Dulles began to receive some good Berlin gossip. The Western Allies achieved nothing like the Russians’ penetration of London, Washington, Berlin and Tokyo, the last through their agent Richard Sorge, working in the German embassy. The US got into the business of overseas espionage only after Pearl Harbor, and focused more effort on sabotage and codebreaking than on placing spies, as distinct from paramilitary groups, in enemy territory. OSS’s Research and Analysis Department in Washington was more impressive than its flamboyant but unfocused field operations. Moreover, I believe that Western Allied sponsorship of guerrilla war did more to promote the post-war self-respect of occupied nations than to hasten the destruction of Nazism. Russia’s partisan operations were conducted on a far more ambitious scale than the SOE/OSS campaigns, and propaganda boosted their achievements both at the time and in the post-war era. However, Soviet documents now available, of which my Russian researcher Dr Lyuba Vinogradovna has made extensive use, indicate that we should view the achievements of the Eastern guerrilla campaign, at least until 1943, with considerable scepticism.

As in all my books, I seek below to establish the ‘big picture’ framework, and to weave into this human stories of the spies, codebreakers and intelligence chiefs who served their respective masters – Turing at Bletchley and Nimitz’s cryptanalysts in the Pacific, the Soviet ‘Red Orchestra’ of agents in Germany, Reinhard Gehlen of OKH, William Donovan of OSS and many more exotic characters. The foremost reason the Western Allies did intelligence best was that they brilliantly exploited civilians, to whom both the US and British governments granted discretion, influence and – where necessary – military rank, as their opponents did not. When the first volume of the British official history of wartime intelligence was published thirty years ago, I suggested to its principal author Professor Harry Hinsley, a Bletchley veteran, that it seemed to show that the amateurs contributed more than did career secret service professionals. Hinsley replied somewhat impatiently, ‘Of course they did. You wouldn’t want to suppose, would you, that in peacetime the best brains of our society wasted their lives in intelligence?’

I have always thought this an important point, echoed in the writings of another academic, Hugh Trevor-Roper, who served in both MI5 and MI6, and whose personal achievement makes him seem one of the more remarkable British intelligence officers of the war. In peacetime, most secret services fulfilled their functions adequately, or at least did little harm, while staffed by people of moderate abilities. Once a struggle for national survival began, however, intelligence had to become part of the guiding brain of the war effort. Clashes on the battlefield could be fought by men of relatively limited gifts, the virtues of the sports field – physical fitness, courage, grit, a little initiative and common sense. But intelligence services suddenly needed brilliance. It sounds banal to say that they had to recruit intelligent people, but – as more than a few twentieth-century sages noted – in many countries this principle was honoured mostly in the breach.

A few words about the arrangement of this book: while my approach is broadly chronological, to avoid leaping too confusingly between traitors in Washington, Soviet spies in Switzerland and the mathematicians of Bletchley Park, the narrative persists with some themes beyond their time sequence. I have drawn heavily on the most authoritative published works in this field, those of Stephen Budiansky, David Kahn and Christopher Andrew notable among them, but I have also exploited archives in Britain, Germany and the US, together with much previously untranslated Russian material. I have made no attempt to discuss the mathematics of codebreaking, which has been done by writers much more numerate than myself.

It is often said that Ian Fleming’s thrillers bear no relationship to the real world of espionage. However, when reading contemporary Soviet reports and recorded conversations, together with the memoirs of Moscow’s wartime intelligence officers, I am struck by how uncannily they mirror the mad, monstrous, imagined dialogue of such people in Fleming’s From Russia With Love. And some of the plots planned and executed by the NKVD and the GRU were no less fantastic than his.

All historical narratives are necessarily tentative and speculative, but they become far more so when spies are involved. In chronicling battles, one can reliably record how many ships were sunk, aircraft shot down, men killed, how much ground was won or lost. But intelligence generates a vast, unreliable literature, some of it produced by protagonists for their own glorification or justification. One immensely popular account of Allied intelligence, Bodyguard of Lies, published in 1975, is largely a work of fiction. Sir William Stephenson, the Canadian who ran the British wartime intelligence coordination organisation in New York, performed a valuable liaison function, but was never much of a spymaster. This did not prevent him from assisting in the creation of a wildly fanciful 1976 biography of himself, A Man Called Intrepid, though there is no evidence that anybody ever called him anything of the sort. Most accounts of wartime SOE agents, particularly women and especially in France, contain large doses of romantic twaddle. Moscow’s mendacity is undiminished by time: the KGB’s official intelligence history, published as recently as 1997, asserts that the British Foreign Office is still concealing documentation about its secret negotiations with ‘fascist’ Germany, and indeed its collusion with Hitler.

Allied codebreaking operations against Germany, Italy and Japan exercised far more influence than did any spy. It is impossible to quantify their impact, however, and it is baffling that Harry Hinsley, the official historian, asserted that Ultra probably shortened the war by three years. This is as tendentious as Professor M.R.D. Foot’s claim, in his official history of SOE in France, that Allied commanders considered that Resistance curtailed the global struggle by six months. Ultra was a tool of the British and Americans, who played only a subordinate role in the destruction of Nazism, which was overwhelmingly a Russian military endeavour. It is no more possible to measure the contribution of Bletchley Park to the timing of victory than that of Winston Churchill, Liberty ships or radar.

Likewise, publicists who make claims that some sensational modern book recounts ‘the spy story that changed World War II’ might as well cite Mary Poppins. One of Churchill’s most profound observations was made in October 1941, in response to a demand from Sir Charles Portal, as chief of air staff, for a commitment to build 4,000 heavy bombers which, claimed the airman, would bring Germany to its knees in six months. The prime minister wrote back that, while everything possible was being done to create a large bomber force, he deplored attempts to place unbounded confidence in any one means of securing victory. ‘All things are always on the move simultaneously,’ he declared. This is an immensely important comment on human affairs, especially in war and above all in intelligence. It is impossible justly to attribute all credit for the success or blame for the failure of an operation to any single factor.

Yet while scepticism about the secret world is indispensable, so too is a capacity for wonder: some fabulous tales prove true. I blush to remember the day in 1974 when I was invited by a newspaper to review F.W. Winterbotham’s The Ultra Secret. In those days, young and green and a mere casual student of 1939–45, like the rest of the world I had never heard of Bletchley Park. I glanced at the about-to-be-published book, then declined to write about it: Winterbotham made such extraordinary claims that I could not credit them. Yet of course the author, a wartime officer of MI6, had been authorised to open a window upon one of the biggest and most fascinating secrets of the Second World War.

No other nation has ever produced an official history explicitly dedicated to wartime intelligence, and approaching in magnitude Britain’s five volumes and 3,000-plus pages, published between 1978 and 1990. This lavish commitment to the historiography of the period, funded by the taxpayer, reflects British pride in its achievement, sustained into the twenty-first century by such absurd – as defined by its negligible relationship to fact – yet also hugely successful feature films as 2014’s The Imitation Game. While most educated people today recognise how subordinate was the contribution of Britain to Allied victory alongside those of the Soviet Union and the United States, they realise that here was something Churchill’s people did better than anybody else. Although there are many stories in this book about bungles and failures, in intelligence as in everything else related to conflict victory is gained not by the side that makes no mistakes, but by the one that makes fewer than the other side. By such a reckoning, the ultimate triumph of the British and Americans was as great in the secret war as it became in the collision between armies, navies and air forces. The defining reality is that the Allies won.

Finally, while some episodes described below seem comic or ridiculous, and reflect human frailties and follies, we must never forget that in every aspect of the global conflict, the stakes were life and death. Hundreds of thousands of people of many nationalities risked their lives, and many sacrificed them, often in the loneliness of dawn before a firing squad, to gather intelligence or pursue guerrilla operations. No twenty-first-century perspective on the personalities and events, successes and failures of those days should diminish our respect, even reverence, for the memory of those who paid the price for waging secret war.

MAX HASTINGS

West Berkshire & Datai, Langkawi

June 2015

* Agents’ codenames in the pages that follow are given within quotation marks.

* Britain’s MI6 is often known by its other name, SIS – the Secret Intelligence Service – but for clarity it is given the former name throughout this work, even in documents quoted, partly to avoid confusion with the US Signals Intelligence Service.

* The Soviet intelligence service and its subordinate domestic and foreign branches were repeatedly reorganised and renamed between 1934 and 1954, when it became the KGB. Throughout this text ‘NKVD’ is used, while acknowledging also from 1943 the counter-intelligence organisation SMERSh – Smert Shpionam – and the parallel existence from 1926 of the Red Army’s military intelligence branch, the Fourth Department or GRU, fierce rival of the NKVD at home and abroad.

* Americans referred to their Japanese diplomatic decrypt material as ‘Magic’, but throughout this text for simplicity I have used ‘Ultra’, which became generally accepted on both sides of the Atlantic as the generic term for products of decryption of enemy high-grade codes and ciphers, although oddly enough the word was scarcely used inside Bletchley Park.

* ‘Humint’ is the trade term for intelligence gathered by spies, ‘sigint’ for the product of wireless interception.