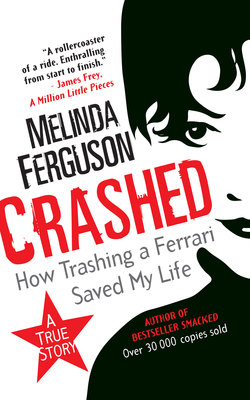

Читать книгу Crashed - Melinda Ferguson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Admissions

ОглавлениеI stared into nothing as I waited on the couch for the woman from Admissions. Fuck, what was her name? I’d been forgetting the most mundane things lately, and it was getting worse and worse. I knew she had told me. Yesterday. When I’d desperately called her, talking in rising hysterical tones from my desk in the open-plan office at The Magazine.

Jeanie … Janie … Jinny? If I made my way through the letters in the alphabet, maybe I’d get it eventually. Sometimes that worked. Genie. That was it! Similar name to that of my oldest sister. My somewhat estranged sibling. It had taken years to rebuild the broken bridges and mayhem caused by Smacked, my tell-all drug memoir. The one that had desecrated me, my family and its belief systems.

Scorched and Burned.

I guess, in writing my story, I had used similar tactics to that adopted by Stalin against the Nazis in World War II. My own Scorched Earth policy – a military strategy that involves destroying, often burning, anything that might be useful to the enemy while advancing through or withdrawing from an area. Somehow, owning your own truth, your own disaster, gives you a little more power than if others own your truth. My book was pretty hardcore stuff, not easily forgotten or forgiven. But somehow of great benefit – and despite the path of destruction it may have left in its wake – to the perpetrator; in my case, to me, the writer. In the case of my family, for many years, it created instant and long-term alienation.

In fact, despite a number of attempts at apology, it took a long time before any real reconciliation with my sister ever took place. These days we were forced to keep a geographical distance. She lived in the north. In Sweden, to be precise. In the ice. I preferred the south. It was warmer.

It takes a lot to say sorry, but perhaps it takes even more to forgive.

She had sounded sweet on the phone, this Hotel Hospital Genie woman. Motherly, even. Not like my stern Germanic mother. Fuck. Suddenly I missed her. It happened sometimes, leaping out of nowhere; a longing for my mom would sweep in, at a traffic light, in a queue. Quite uninvited, it would arrive like a black crow and nestle in my neck and drag out my tears.

She’d been buried almost a decade. Cremated, actually. Even though our mother was never one who would go along with any of those Eastern beliefs, my sister had insisted that she be burned. With death, our mom had lost her right to argue.

At the end all we had was a little box of ashes. I don’t think my mother would have approved.

Truth be told, I hadn’t really liked her. Loved her – sure, she was my only parent – but liked? No, not very much at all when she’d been alive.

But here, about to check into this strange clinic that looked like a hotel, I felt my aloneness, my umbilical cordless-ness so acutely that the ache all but ripped right into the place where they had once cut and tied the feeding line at birth. I had never felt further away from a place called home, even when I had been homeless. A little speck spinning in some faraway black hole. Lost out there in the horizonless Star Trek of a place they call space.

The feeling of free falling might have had something to do with the fact that I had hardly told a soul I was heading here. Not even my brother. The one person I did tell, however, was my publisher at The Magazine. Concerned by my recent downward spiral, I think she was relieved to see me go off to get help.

It must have been hard not to notice that I had been growing progressively more fucked up at work since The Crash. Drowning daily in a symphony of wayward sobs. Sometimes hourly. Over the past six months, tears had spread like the slime of nuclear waste; I had shed so many that they had all but eaten through the thread-bare office carpet that coated the floor beneath my swivel chair.

But yesterday was by far the worst. Even before I got in to work, the tears had already taken me hostage. Although who could blame me really? After what happened on The Weekend.

By the time the two young journos I managed got to the office, I was crouched on the floor. Half kneeling, and rocking like a crazy daisy. Awkwardly, they tried to comfort me, but as I looked up helplessly at them, I noticed the “What the fuck are we to do with the boss?” fear in their eyes. That really made me howl. I didn’t care that by this stage 30-or-so people, including the entire Sales and Marketing team and writers from two other magazines, were peering over from their desks. I felt no shame. The ability to control myself had long since left as I leopard crawled back to my station.

It was at that point that I Googled the clinic. A white mansion-like building filled the screen. It looked like airbrushed heaven, or at the very least, like a five-star hotel. Sounds of tranquillity accompanied the visuals. They may have mixed in a few early-morning bird calls, which faded into a stream bubbling over smooth pebbles … Contact numbers appeared on the top left of the screen. The toll free 086 number was discreet.

So I had made the call.

Now, perched on the edge of the leather couch in reception, I prayed no one I knew would see me. What if someone from Narcotics Anonymous had booked in? Or perhaps someone I knew was working as a counsellor here? I knew a few addicts who had done that. Become counsellors when they got clean. They had usually fucked up their lives so badly – lying, stealing, running from the cops and SARS – that they were mostly unemployable, so had little choice but to open rehabs. Establish secondary care, halfway establishments. Sober houses.

To give nobility to the cause, someone would inevitably quote Step 12 of the programme: “Help the addict who still suffers.” But in some instances it looked, to me, a lot like the blind leading the blind, and over time I had grown increasingly suspicious that many of those who established these “recovery” facilities had ulterior motives: ego and money. The two were intertwined. In fact, some of them were actually more wasted in the head than the addicts they were taking large amounts of money from to “help”. And then of course there were the Svengalis who used their sexual magnetism to prey on newly clean addicts, who invariably fell to pieces after they’d been fucked with and often went back “out there” to use again. A lot came close to dying, some even did.

Sitting in reception, I suddenly saw the insanity of my train of thought. Here I was, at this pathetically low juncture in my life, and I was taking the world’s inventory. That’s what we addicts often do; the more fucked up we feel inside, the easier it is to glare at the world and shoot scud missiles at anything that moves.

At this inglorious point of my existence I’d slid right down to Step 1, blubbering my way back to “I came to believe that my life was unmanageable”. Lately I had really been struggling to admit that there was a power greater than me that could restore my sanity.

I hadn’t been to a meeting in months. It felt like the more fucked up I was getting, the more I was struggling to get into the circle of NA again. I knew this was a bad place for me to be. In fact, the last time I had actually really shared at a meeting was on 1 September 2013. My 14-year clean birthday. The Crash had happened on 2 September.

Right now, as I peeped from behind my blinkers and confronted the state of my being, I was terrified. How could it all have gone so horribly wrong?

“Hey, Mel! What are you doing here. Have you come to share?”

Fuckfuckityfuck. Just what I’d dreaded. I recognised the voice immediately. “My name is Jax – I’m an addict” – an older guy I’d met in Yeoville back in the nineties. Before I’d started smoking heroin and crack. Jax, who had once walked up and down Rocky Street, bare-footed and unkempt, selling wind chimes to feed his intravenous smack habit. Although I had noticed back then how swollen and purple his sandalled feet always looked, I had been innocent enough to be entirely unaware of the ravages that heroin leaves behind.

Today expensive trainers covered those toes.

He had always been cool to me, especially in those early days when I stumbled into the rooms of recovery, fresh off the streets of Hillbrow, crack-skittish, skinny and coughing like a hag. He’d welcomed me.

He had been almost two years clean by the time we had reconnected at one of my first NA meetings back in 1999. Two whole fucking years. That had seemed like an impossibility for me back then. Stringing 24 hours together felt like Everest. Never mind a full 365 days x 2 = 730 fucking days. No fucking way could I even begin to grasp that.

Clean-shaven, smiling and employed, I’d barely recognised him. Later I would become tremendously inspired by the transformation I saw in him.

At six weeks clean and sober, I think I’d stuck my hands down his pants, somewhere in the Karoo, on the way to a convention in Cape Town. Why couldn’t I remember details? Oh fuck, had I given him a blowjob? The once-murky memory suddenly started shifting sharply into focus. And now, here in reception at the Hotel Hospital, I found myself staring blankly at him. The image of me going down on him wouldn’t let up. He had this weird smile on his face. Like he remembered too.

But what the hell was he doing here? Oh fuck. Of course, now I remembered – he worked here.

He was one of the few addicts-turned-counsellors who did know what he was doing. There was no way I could get away, spirit myself away and out of this one.

“Burnout, no sleep, my nine-year relationship’s over. And I crashed a car. I haven’t relapsed – it’s just that I’m fucked. Can’t stop crying,” I muttered, before a deep hiccup released a torrent of sobs. Jesus! Now I dissolved into another flood of tears. No hiding, no pretences. Fuck. Why did I always have to blurt it all out like some errant hosepipe. Now it was probably going to get out, slide away like a sick snake of rumour: “You hear? She’s relapsed … Oh, my word, after 14 years! Can you believe it?” Those toxic little addicts always feasting and burping like maggots on chaos to make themselves feel better.

“I haven’t relapsed …” I said it again, before finally petering out. A pathetic bleat. As though relapsing was some terrible, seeping venereal disease.

“That’s cool. Don’t worry,” he awkwardly tried to comfort me. “I won’t say anything. I work here – anonymity and all, you know. Part of the job. Everyone’s got burnout. It’s a New Millennium thing. Sometimes I wish I could book in myself. You’re doing the right thing.” And then, as he moved away, he grinned. “Welcome to The Clinic.”

His attempts at comforting me, consoling me, left no impression. I was too way gone for sweet talk. Maybe I had relapsed? I obsessed. Maybe I had gone swinging like a pendulum backwards into that never-ending cycle of need: use-greed-use-need-greed-use.

Relationship addiction. Work addiction. Crazy thought addiction. Facebook. Instagram … And then this fucking thing with food. And actually, while I was at it, probably sex addiction too.

“You’re in relapse mode,” my longtime therapist, Dr ParaFreud, with little round shrink glasses, whom I hadn’t spoken to in three years, had told me when I called him on his cellphone that Sunday – family time, out of office – without even wondering whether I was being inappropriate. “Unbounderised,” he would have called it.

“As much as you are in some type of crisis, don’t you think you are being a little over dramatic, Melinda? I don’t think you actually need to book into a treatment centre. You’re successful, you’ve written books, published books. You have your life together. I think you’re just going through a hard time. You just need to realign things, put new boundaries in place. Keep going to therapy.”

And on some level he was right. Maybe I was being extreme. I’d always been a bit of a drama queen – I’d been told that often enough. Another thing to throw into the Addiction closet, Addicted to Drama. I had even got a degree in it from UCT. “Why you’d need to study it – Drama – I’ll never know,” my mother had often said. “Your whole life’s an act. You are one big drama.”

My mother’s cruelty, her sharp, uncensored tongue, had the power to hurtle me into alleyways of self-doubt. I remember those deflated moments well. The way her words cut me up like soggy stir-fry.

Genie arrived with the forms. She informed me medical aid had approved the “hospitalisation”. Fuck. Hospitalisation at Hotel Hospital. That was serious. Plus, I’ve always been suspicious of the use of too much alliteration …

Were they going to put me on a drip, the dreaded intravenous approach? Hook me up with nasty needles?

I signed on the dotted line.

“I’m only staying for seven days,” I snarled.

She smiled and nodded.

She instructed me to wait on the couch to be taken up to the nurses’ station. Now there was no going back, no reversing.

My mind once again hurtled back to what Dr ParaFreud had advised me. Sure, he may have been right about the outwardly successful part. For more than a decade I had been more than holding it together: author of two bestselling books on addiction. The third on township pop princess Kelly Khumalo, which had sold rather well. I had just finished my fourth – on that stump-legged athlete – which was waiting in the wings to be published. An award-winning magazine writer turned publisher. On the outside, it all looked fabulous … Here I was, a well-paid speaker at functions touted on my agent’s website as a Famous Speaker under the category of Inspirational. Paid thousands to talk for less than an hour on my journey to hell and back.

“Manifest your lives,” I’d tell the audience. “Inspiring”, “strong”, “courageous” are what other people called me.

I had money in the bank. Fifty pairs of shoes in my closet. I even had a Kate Unger dress for meetings to impress. I did all my banking online with a zooty app on my iPad Air. I had almost paid off my bond. I had medical aid, retirement funds and life insurance. I had Voyager miles, eBucks and Vitality points. I could even choose which lounge I wanted to chill in when I was travelling by air, for fuck’s sake.

But since when did a person’s outsides become a barometer for the catastrophes we carry inside? The voice inside sneered.

And why, you might ask, in the light of all I had achieved and owned, was I falling about on the floor in floods of tears? Like my epiglottis was about to throttle me? As desperately as I wanted to believe Dr ParaFreud, I knew that this time he was wrong. This time there really was something wrong. If there was one thing I had learned for sure over the years, it was: never judge a person’s insides by their outsides.

“You probably just need to go to a few NA meetings, and get your life back on track.” Those were the last words Dr PF had said to me.

The last meeting I had attended was the day before The Crash.