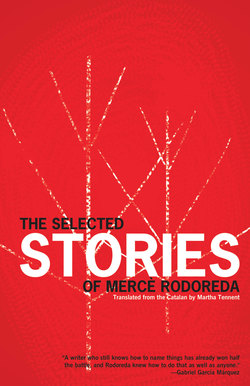

Читать книгу The Selected Stories of Mercè Rodoreda - Mercè Rodoreda - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Threaded

Needle

ОглавлениеShe sighed deeply, sat down, and picked up her sewing from the table. The white satin glistened like sun-pierced water in the light cast by the floor lamp; a fantastical painter had decorated the parchment lampshade with pyramids surrounded by a landscape of sepia palm trees. Gold lettering on the satin selvage indicated the manufacturer and quality: germain et fils—caressant.

Maria Lluïsa threaded the needle, cut the thread with her teeth, knotted it, and stuck the threaded needle in her bathrobe, above her breast. I wonder what the bride’s like? She never saw the customers. Mademoiselle Adrienne, the workroom manager, fitted and prepared the clothes; once they had been cut and basted they were sent to the workers. I wonder what she’s like? Blond? Brunette? She only knew the woman’s size: forty-eight. She must look like a sack of potatoes.

She laughed and reached up to unfold the nightgown. On the left was a piece of puckered lace. It’s almost as if they do it on purpose to waste my time. She positioned the nightgown on the mannequin, undid the basting on the puckered section, and secured it with needles. She worked, lost in thought, her mouth partially open, the tip of her tongue against her teeth. She was calculating how long it would take her to sew the lace. Thirty-six hours, if she was alert. She would tell the shop it was forty-two. After all, if she was sharp on the job, no reason to do any favors. Six hours for each garland. She would need to go over the design, leaf by leaf, flower by flower; then she would cut the tulle and pop it out. It was a delicate job that demanded skill and patience. Forty-two hours at eighteen francs.

She removed the nightgown from the mannequin, put on her thimble, and picked up the needle. She loved her job for many reasons; it allowed her a glimpse of a world of luxury, and because her hands worked mechanically, she could dream. That’s why she preferred to work at home and at night. When she arrived from the workroom with a new sewing job, she would undo the package slowly and caress the silks and lace edgings. If a neighbor came up to admire the delicate sewing, she proudly displayed it, as if the fine silks and crêpes were for her. The blues and pinks, the occasional lavender, soothed her tired, unwedded heart.

She sewed quickly. With great confidence she pushed the needle in and jerked the thread out. From time to time she would lift the fabric that slid toward the floor and return it to her lap with a precise gesture. Her light chestnut hair was swept back, revealing a few shiny silver threads. On both sides of her small mouth, two deep wrinkles hardened her congested face.

Three or four years from now I’ll set up business for myself. I’ll hang a brass sign on the door: maria lluïsa, bridal seamstress. At the workroom they would be green with envy. Especially Mademoiselle Adrienne. They had worked together for ten years—and cordially despised each other, both of them living in constant exasperation at not knowing how much money the other had. Sometimes Adrienne came up from the fitting room with a package and hid it under the counter, without a word, like a magpie. When Maria Lluïsa saw her coming back with a package, she would grow pale with irritation, a wave of blood rising to her forehead, spreading slowly, leaving shiny, red blotches on her cheeks and the tip of her nose. I’ll have girls working for me and design the clothes myself. The shop will be in my name and customers will lavish me with presents. Better that than getting married. Cooking for a man, washing his clothes, having to put up with a man day and night, only for him to look at young girls when I’m old. She smiled and cast a condescending glance at the bridal nightgown.

But before the dream could absorb her . . .

Of course, he would probably die soon enough. She imagined him as he had looked two weeks before, his white hair, his restless, eager eyes and sunken cheeks, shaking with an almost imperceptible tremor beneath his old, stained cassock with the shiny elbows and frayed cuffs. The first day she sat with him at the hospital she heard two nurses whispering: “She’s the priest’s cousin.” She had worn her dark hat with the black bird, its wings spread toward the right. Over the years, one of the bird’s eyes had disappeared and dust had settled in the empty eye socket. She didn’t dare brush it for fear the feathers would come out. She would have it redone in the spring. I’ll tell them to remove the bird and add a pretty little bunch of flowers.

She yawned, dug the needle into the sewing, and rubbed her eyes. She had slept badly for seven nights, the nights she had watched over him, half seated, half stretched out in an armchair. When the doctor told her cousin he would have to be admitted to a hospital, he had someone contact her. “I’ll deposit a hundred thousand francs in your name; you may need the money if I’m sick for a long time. Operations are expensive, and I’d like you to take care of everything. You know if anything happens to me, everything I have is yours.” She had kept the fact that he was sick from the other relatives: What if in the end, in a moment of weakness, he put the old quarrels behind him and decided to leave them something? She alone had watched over him; and she would have spent the night sitting in the armchair by the head of his bed, if the shop hadn’t given her the urgent sewing. He would have greeted her like every night, with a feeble, wasted smile. “Thank goodness I have you, Maria Lluïsa.” And then, like every night, she would scrutinize his waxen face, marked by vague shadows, life blazing in his eyes.

She removed the thimble, picked up the scissors, and started to cut the extra tulle. She couldn’t be distracted now; an irreparable snip of the scissors was easily made. Adrienne went over her work meticulously. Nothing escaped her, not the vaguely crooked seam, not the occasional long stitch. “I don’t like these pleats, Maria Lluïsa.” She had a stray eye, and to look at the sewing she had to hold the material in front of her nose. It was almost as if the devil had given her some sort of miraculous double vision.

That winter she had gone to work every afternoon so she wouldn’t have to light a fire at home. One day she arrived a bit late, and they were talking about her. She stopped on the landing and listened: “When I got there, the priest was sitting in the dining room.”

It was the elderly Madame Durand, a tall, pale woman who did the ironing and lived in a perpetual state of irritation. The others were laughing. What were they thinking about her?

They wouldn’t be able to say a thing now. When her cousin was released from the hospital, he would live with her. They would hire a maid. He would be an easy patient, a tube to pee in, a saintly man who would spend his days praying, waiting patiently for death.

She finished sewing another flower. This is how she would grown old: bent over her sewing.

“Maria Lluïsa,” he used to call to her when they were little, “want to look for frogs with me?”

“When I finish cleaning the chicken coop.”

If his parents hadn’t made him study to become a priest, he might have married her. But at that time he was the son of the poorest sister and hadn’t yet gotten his inheritance from his uncle in Dakar. He was a sickly little boy who always wore a scarf around his neck, fastened with a safety pin.

A sharp thud in the kitchen banished the ghosts. She placed the nightgown on the table and went to see what had happened.

•

Picarol was sleeping in the corner. The light must have woken him. He got up, stretched his front paws far in front of him, and arched his back.

“Don’t be afraid, Picarol.”

She examined the kitchen with an anxious eye. Above the stove stood half a dozen white glass jars.

The tomato must have fermented.

She found one of the lids lying on the gas burner. She smelled the jar before she replaced the lid. Another liter of canned tomatoes ready to be thrown out. She opened the cupboard and glanced at the provisions with satisfaction. Chocolate, cookies, a tin of coffee, another of tea, five kilos of sugar, a row of ceramic jars filled with duck and chicken covered in animal fat. The marmalades were on the top shelf. And two bottles of rum: two! All that in the middle of the war. He might want a little glass of rum every day, and rum . . .

She was filled with sadness as she left the kitchen. Those provisions had cost her a lot of money and maneuvering. A lot of chasing people and doing them favors. She watched over them as if they were a treasure. When her cousin moved in they would share them. At midnight she often drank a cup of hot chocolate, but only on really cold nights, purely out of necessity, to be able to work till dawn. Maybe he liked hot chocolate too.

•

“Yes?”

Someone had knocked on the door, then pushed it ajar. A head with lively, happy little blue eyes appeared.

“Can I come in?”

Palmira lived in the apartment beneath her. Ever since Maria Lluïsa’s cousin had been in the hospital, her neighbor had cooked for her, brought her two hot water bottles every night.

“You mean it’s already eleven o’clock? Time goes so fast.”

“It flies, it flies! And you work much too hard. Don’t move. I’ll put them in the bed for you. Better to do it quick, while they’re still hot.”

Palmira headed to the bedroom. I should give her a collar; I’ll get Simona to sew the edge. She’s faster than me.

“How’s your cousin?”

Palmira had come out of the bedroom, rubbing her hands with lotion. She was missing the index finger on her right hand. Folds of skin formed a swirl at the tip of a cluster of useless flesh.

“A bit better. He might be released in a couple of weeks. But he’s very weak.”

“Poor man! It’s one thing if he gets his health back, but I can’t see you having another person in the house, someone so sick.”

Palmira stood in front of her, admiring the nightgown as Maria Lluïsa continued to sew.

“If only I didn’t have to work for a living! I would even enjoy sewing, but . . .” What a bore. Couldn’t she just leave?

“And all the medication; it must be terribly expensive.”

Palmira couldn’t take her eyes off the mountain of brilliant snow that she dared not touch. If I show her the nightgown, she’ll stay another hour.

“Come on, Palmira, off to bed, you have to get up early.”

Palmira sighed and headed for the door with a sense of regret. “Good night. Don’t be up too late.”

•

Yes, the medicine was expensive. First the hospital, then the surgeon, now all the medication. What would be left of the hundred thousand francs? The stack of bills would slowly dwindle. “One operation might not be enough. If it isn’t, he’ll need a second,” the physician had said as he looked at her apologetically, wiping his glasses with a splendidly white handkerchief. What if one operation proved not to be enough, and he decided at the last moment to leave his money to the other relatives? That would really upset things. Of course she could always . . . Then everything would work out. But how could she do it without anyone realizing? She wouldn’t be the first to try it. Or the last. Increase the dose, little by little. He was already so weak; everyone said it was a lost cause. He would probably live only a few months.

Dr. Simon had been her physician for years, a kindly old soul, a bit absentminded, only kept a few of his former patients. He would never even notice. His house calls were more like visits from an elderly, tiresome relative than a doctor. Twenty-five, thirty, thirty-five drops. Two months and it would be over. How could she be sure? When she went to the pharmacy to buy the drops, she would wait until the place was empty. When she had paid and was holding the bottle, her hand on the door about to leave, she would turn around: “Senyor Pons, this medicine isn’t dangerous, is it? If I lose count one day, I don’t suppose it would matter.” Maybe the pharmacist would say: “Oh no, be very careful, only twenty drops.” I would have to ask in a very natural tone, with maybe just a touch of uneasiness. “Well, it’s best to know.” Senyor Pons was very neat. He would scratch his white beard and smile at her above his glasses, lowering his head a bit between the two large glass spheres that stood on the counter, one green, the other a caramel color. A small bottle with a rubber dropper. The glass would be cold, the liquid murky. He wouldn’t suffer at all. It would really be for his own good. He would fade away, slowly withering.

She could set herself up right away. An apartment in the center of town, on Cours Clémenceau, for example, near Place Tourny. A parlor with two balconies overlooking the street, half a dozen armchairs upholstered in cream-colored damask, a mirror with a gold frame, a few antique fashion engravings scattered about the walls. She would have the workshop at the back, by the gallery. Nice and sunny. I’ll take Simona with me—she does the best edging—and Rosa, the best embroiderer. She would take the two girls from Indochina who worked for hours without opening their mouths, quiet as a pair of cats, only raising their heads to smile. She didn’t want Madame Durand; she would find herself a good ironer, that would be easy enough. Adrienne would be dumbstruck when she saw that her best workers had abandoned her, left her high and dry! She would go to Paris every year to look for new designs. She would ride first class, wagon lit, with velvet seats and a shiny ashtray by the window. At the beginning of each season, she would send cards, printed with calligraphic swirls framing her name in English script, to her clients. Perfumed cards. She would keep them in a cushioned box where she had sprinkled drops of perfume . . . If she increased the number of drops too quickly, she could be caught. And he might suffer. Some time ago she had read The Pink Shadow, where an attorney poisoned three people over some stolen documents. He laced their coffee with arsenic. She had lent the book to Adrienne; all the girls in the shop had read it. Drops were the surest method. Twenty-five, then thirty. Her hand would shake a bit, and the glass dropper would rattle against the glass. One, two, three, four. Perfect round drops that would become slightly deformed from the weight as they slid from the dropper. When they hit the water they caused a tiny mist. Five, six, seven.

The Cathedral clock struck twelve. She opened wide her round eyes as if she had just woken up. What was I thinking?

The needle was out of thread; she would have to start another. She yawned. Suddenly, mid-yawn, she became conscious of what she had been imagining and was terror-stricken. She closed her mouth slowly and rubbed her eyes.

“Oh my God!” She placed the sewing on the table. She was sleepy, her eyes hurt, she should go to bed. She removed her smock, sweater, skirt, wool slip and stood in her undershirt and pink knitted breeches that reached down to her knees. She glanced at the bridal nightgown. I wonder how it would look on me. She stood in front of the mirror on the wardrobe and tried it on. She was thin, and the nightgown was much too large for her. She tied it at the waist, held out the skirt with both hands, and spun around.

If I had married my cousin, I would have made myself a white, white nightgown. Just like this one.

She felt a knot in her throat, something gripping her neck. Her eyes filled with tears.

“What an idiot you are!”

Slowly she removed the nightgown, folded it carefully, and left it on the chair before switching off the light. She climbed into bed in the dark.

She was still weeping when the sun came up.