Читать книгу Sea Loves Me - Mia Couto - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

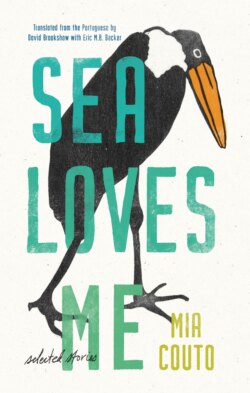

The Whales of Quissico

ОглавлениеHe just sat there. That’s all. Sat stock-still, just like that. Time did not lose its temper with him. It left him alone. Bento João Mussavele.

But nobody worried about him. People would pass by and see that deep down he wasn’t idle. When they asked what he was doing, the answer would always be the same:

—I’m taking a bit of fresh air.

It must have really been very fresh when, one day, he decided to get up.

—I’m off.

His friends thought he was going back home. That he had finally decided to work and start planting a machamba. The farewells began.

Some went as far as to contest him:

—But where are you going? Where you come from is full of bandits, man.

He did not pay them any attention. He had chosen his idea, and it was a secret. He confided it to his uncle.

—You know, Uncle, there’s such hunger back there in Inhambane. People are dying every day.

And he shook his head as if commiserating. But it had nothing to do with sentiment: just respect for the dead.

—They told me something. That something is going to change my life.

He paused, and straightened himself in his chair:

—You know what a whale is … well, I don’t know how …

—A whale?

—That’s what I said.

—But what’s a whale got to do with it?

—Because one appeared at Quissico. It’s true.

—But there aren’t any whales; I’ve never seen one. And even if one did appear, how would people know what the creature was called?

—People don’t know the name. It was a journalist who started spreading this story around about it being a whale or not a whale. All we know is that it’s a big fish which comes to land on the beach. It comes from the direction of the night. It opens its mouth and, boy, if you could see what it’s got inside … It’s full of things. Listen, it’s like a store, but not the ones you see nowadays. It’s like a store from the old days. Full. I swear I’m being serious.

Then he gave details: people would come up to it and make their requests. Each one depending on what he needed, exactly so. All you had to do was ask, just like that. No formal requisitions or production of travel papers. The creature would open its mouth and out would come peanuts, meat, olive oil. Salt cod, too.

—Can you just imagine it? All a fellow would need is a van, he’d load the things, fill it up, drive it here to the city. Go back again. Just think of the money he’d make.

His uncle laughed long and loud. It seemed like a joke.

—It’s all pie in the sky. There is no whale. Do you know how the story began?

He made no reply. It was a wasted conversation, but he kept up the good-mannered pretense of listening, and his uncle continued:

—It’s those folk there who are hungry. Very hungry. They start inventing these apparitions, as if they were wizardry. But they’re just figments of the imagination, mirages …

—Whales, corrected Bento.

He was unmoved. All this doubting wasn’t enough to make him give up. He would go around asking, he would find a way of getting together some money. And he set about doing just that.

He spent the whole day wandering up and down the streets. He spoke to Aunt Justina, who had a stall in the market and with Marito, who had a van for hire. Both were skeptical. Let him go to Quissico first and bring back some proof of the whale’s existence. Let him bring back some goods, preferably some bottles of that water from Lisbon,1 and then they might give him a hand.

Then one day he decided to seek better advice. He would ask the local wise men, that white, Senhor Almeida, and the Black who went by the name of Agostinho. He began by consulting the Black. He gave a brief summary of the matter in question.

—In the first place, replied Agostinho, who was a schoolmaster, the whale is not what it seems at first sight. Whales are prone to deceive.

He felt a lump in his throat, as his hopes began to crumble.

—I’ve already been told that, Senhor Agostinho. But I believe in the whale; I have to believe in it.

—That’s not what I meant, my friend. I was trying to explain that the whale appears to be that which it isn’t. It looks like a fish but it isn’t one. It’s a mammal. Just like you and me, for we are mammals.

—So we are like the whale? Is that what you’re saying?

The schoolmaster spoke for half an hour. He made a great show of his Portuguese. Bento stood with his eyes wide open, avidly taking in the quasi-translation. But if the zoological explanation was detailed, the conversation did not satisfy Bento’s intentions.

He tried the white man’s house. He walked down the avenues lined with acacias. On the sidewalks, children played with the stamens of acacia flowers. Just look at it, everybody mixed together, white children and Black. Just like in the old days …

When he knocked at the wire mesh door of Almeida’s residence, a houseboy peeped through suspiciously. With a grimace he overcame the bright light outside, and when he saw the colour of the visitor’s skin, he decided to keep the door closed.

—I’m asking to speak to Senhor Almeida. He already knows me.

The conversation was brief, Almeida answered neither one way nor the other. He said the world was going crazy, that the earth’s axis was more and more inclined and that the poles were becoming flatter, or flatulent, he didn’t quite understand.

But that vague discourse gave him hope. It was almost like a confirmation. When he left, Bento was euphoric. He could see whales stretched out in rows as far as the eye could see, dozing on the beaches of Quissico. Hundreds of them, all loaded and he reviewing them from an MLJ station wagon.

With the little money he had saved he bought a ticket and left. Signs of war could be seen all along the road. The charred remains of buses coupled with the wretchedness of the machambas punished by drought.

Is it only the sun that rains nowadays?

The gas fumes produced by the bus in which he was travelling seeped in among the passengers, who complained, but Bento Mussavele was miles away, already visualizing the coast of Quissico. When he arrived, it all seemed familiar to him. The bay was fed by the waters from the lagoons of Massava and Maiene. That blue which melted away before one’s eyes was beautiful. In the background, beyond the lagoons, there was land again, a brown strip which held the fury of the ocean in check. The persistence of the waves was gradually creating cracks in that rampart, embellishing it with tall islands which looked like mountains emerging from the blue in order to breathe. The whale would probably turn up over there, mingling with the grey of the sky at the end of the day.

He climbed down the ravine, his little satchel over his shoulder, until he reached the abandoned beach houses. In times gone by, these houses had accommodated tourists. Not even the Portuguese used to go there. Only South Africans. Now, all was deserted and only he, Bento Mussavele, ruled over that unreal landscape. He settled in an old house, installing himself among the remains of furniture and the ghosts of a recent age. There he remained without being aware of the comings and goings of life. When the tide came in, no matter what the hour, Bento would walk down to the surf and stay there staring into the gloom. Sucking on an old unlit pipe, he brooded. It must come. I know it must come.

Weeks later, his friends came to visit him. They risked the journey on one of Oliveira’s buses, each bend in the road a fright to ambush the heart. They arrived at the house after descending the slope. There was Bento slumbering amid aluminum camping dishes and wooden boxes. A tatty old mattress lay decomposing on a straw mat. Waking with a start, Bento greeted his friends without any great enthusiasm. He confessed to having developed a certain fondness for the house. After the whale, he would get some furniture, of the type that can be stood up against the wall. But his most ambitious plans were reserved for the carpets. Anything that was floor, or looked like it, would be carpeted. Even the immediate vicinity of the house too, because sand is annoying and seems to move together with one’s feet. And there would be a special carpet which would extend along the sands, joining the house to the place where the selfsame whale would disgorge.

Finally, one of his friends let the cat out of the bag.

—You know, Bento: back in Maputo it’s being rumoured you’re a reactionary. You’re here like this because of this business of arms, or whatever they’re called.

—Arms?

—Yes, another visitor chipped in helpfully. You know that South Africa is supplying the bandits. They receive arms which come by way of the sea. That’s why they’re talking a lot about you.

He began to fret.

—Hey, boys, I can’t sit still anymore. I don’t know who’s receiving these arms, he kept repeating.

—I’m waiting for the whale, that’s all.

They argued. Bento remained in the forefront of the discussion. Who could be certain that the whale didn’t come from the socialist countries? Even the schoolmaster, Senhor Agostinho, whom they all knew, had said that all he needed now was to see pigs fly.

—Hold it there. Now you’re starting on a story about pigs before anyone’s even seen the stupid whale.

Among the visitors there was one who belonged to the cadres and who said there was an explanation. That the whale and the pigs …

—Wait, the pigs have nothing to do with …

—Okay, leave the pigs out of it, but the whale is an invention of the imperialists to stultify the people and make them always wait for food to arrive from abroad.

—But are the imperialists making up this story of the whale?

—They invented it, yes. This rumour …

—But who gave eyes to the people who saw it? Was it the imperialists?

—Okay, Bento, you can stay, but we’re going now.

And his friends left, convinced that there was sorcery at work there. Somebody had given Bento medicine to make him get lost in the sands of that idiotic expectation.

One night, with the sea roaring in endless anger, Bento awoke with a start. He was trembling as if suffering a bout of malaria. He felt his legs: they were burning. But there was some sign in the wind, some sense of foreboding emanating from the darkness, which obliged him to get up and go outside. Was it a promise? Or was it disaster? He went over to the door. The sand had come away from its resting place and seemed like a maddened whip. Suddenly, underneath the little whirlwind of sand, he saw the large mat, the same mat he had laid in his dream. If it were true, if the carpet were there, then the whale had arrived. He tried to adjust his eyes as if to discharge his emotion, but giddiness overturned his vision and his hands sought the doorpost for support. He set off through the sand, stark naked, tiny as a seagull with broken wings. He could not hear his own voice, he did not know whether it was he who was shouting. The voice came nearer and nearer. It exploded inside his head. Now he began to wade into the sea. He felt it cold, burning his tense nerves. Further ahead of him there was a dark patch which came and went like the throbbing heart of a hangover. It could only be that elusive whale.

As soon as he had unloaded the first items of merchandise, he would give himself something to eat because hunger had been vying for his body for a long time now. Only afterwards would he see to the rest, making use of the old crates in the house.

He thought about the work that remained to be done as he advanced through the water, which now came up to his waist. He felt lighthearted, as if anguish had drained his soul. A second voice addressed him, biting his last remaining senses. There is no whale, these waters are going to be your tomb, and punish you for the dream you nourished. But to die just like that for nothing? No, the creature was there, he could hear it breathing, that deep rumble was no longer the storm, but the whale calling for him. He was aware that he could hardly feel anything anymore, just the coldness of the water lapping at his chest. So it was all an invention, was it? Didn’t I tell you that you needed to have faith, more faith than doubt?

The only inhabitant of the storm, Bento João Mussavele, waded on into the sea, and into his dream.

When the storm had blown itself out, the blue waters of the lagoon subsided once again into the timeless tranquility of before. The sands took their proper place once more. In an old abandoned house remained Bento João Mussavele’s untidy heap of clothes, still warm from the heat of his final fever. Next to them was a satchel containing the relics of a dream. There were some who claimed that those clothes and that satchel were proof of the presence of an enemy who was responsible for receiving arms. And that these arms were probably transported by submarines which, in the tales passed on by word of mouth, had been transformed into the whales of Quissico.