Читать книгу Sea Loves Me - Mia Couto - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

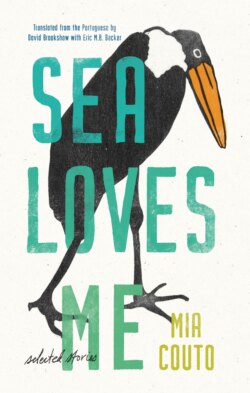

2. Wings on the ground, embers in the sky

ОглавлениеLight was getting thin. Only a glassful of sky was left. In my brother-in-law Bartolomeu’s house, they were preparing for the end of the day. He glanced round the hut: his wife bustled about, causing the last shadows from the oil lamp to flicker. Then his wife went to bed, but Bartolomeu was restless. Sleep wouldn’t come quickly to him. Outside an owl began to hoot calamities. His wife didn’t hear the bird warning of death, she was already in the arms of sleep. Bartolomeu said to himself: I’m going to make tea: maybe that’ll help me to sleep.

The fire was still burning. He took a stick of wood and blew on it. He shook the crumbs of flame from his eyes and in the confusion dropped the lighted stick on his wife’s back. The cry she let out no one had ever heard the likes of before. It wasn’t the sound a person would make, it was the howl of an animal. A hyena’s voice for sure. Bartolomeu jumped with fright: What am I married to then? A nóii? Those women who turn into animals at night and go around doing witches’ work?

His wife dragged her burning pain across the floor in front of his distress. Like an animal. What a luckless life, thought Bartolomeu. And he fled from home. He hurried across the village to tell me what had happened. He arrived at my house, and the dogs were very excited. He came in without knocking, without so much as an “excuse me.” He told me his story just as I am writing it down. At first, I didn’t believe him. Perhaps Bartolomeu had mixed up his recollections when drunk. I smelled the breath of his complaint. It didn’t smell of drink. It was true then. Bartolomeu repeated the story two, three, four times. I listened to it and thought to myself: And what if my wife is the same? What if she’s a nóii too?

When Bartolomeu had left, the idea seized hold of my thoughts. And supposing I, without knowing it, were living with an animal-woman? If I had made love to her, then I had traded my human’s mouth with an animal snout. How could I excuse such a trade? Were animals ever supposed to rest on a sleeping mat? Animals live and grow strong out in the corrals, beyond the wire. If that bitch had deceived me, I had become an animal myself. There was only one way to find out whether Carlota Gentina, my wife, was a nóii or not. It was to surprise her with some suffering, some deep pain. I looked around and saw a pot full of boiling water. I picked it up and poured the scalding liquid over her body. I waited for the scream but it didn’t come. It didn’t come at all. She just lay there crying silently, without making a noise. She was a curled-up piece of silence there on the mat. All the following day she did not move. Poor Carlota was just a name lying on the ground. A name without a person: just a long, slow sleep inside a body. I shook her by the shoulders:

—Carlota, why don’t you move? If you’re in agony, why don’t you scream?

But death is a war of deceptions. Victories are just defeats which have been put off. As long as life has a purpose to it, it will build a person. That’s what Carlota was in need of: the lie of a purpose. I played the fool to make her laugh. I hopped round the mat like a locust. I clanked cooking pots against each other and spilled the noise over myself. Nothing. Her eyes remained glued to the far distance, gazing at the blind side of darkness. Only I laughed, wrapped up in my saucepans. I got up, breathless with laughter, and went outside to give vent to my mad guffaws. I laughed until I was tired. Then gradually I was overcome by sad thoughts, ancient pangs of conscience.

I went back inside and thought she would probably like to see the light of day and stretch her legs. I took her outside. She was so light that her blood could have been no more than red dust. I sat Carlota down facing the setting sun. I let the fresh air soak her body. There, sitting in the backyard, my wife Carlota Gentina died. I didn’t notice her death immediately. I only knew it when I saw the tear which had stopped still in her eyes. That tear was already death’s water.

I stood looking at the woman stretched out in that body of hers. I looked at the feet, torn like the surface of the earth. They had walked so many paths that they had become like brothers to the sand. The feet of the dead are big, they grow on after death. While I measured Carlota’s death I began to have my doubts: What illness was it that caused neither swelling nor cries of pain? Can hot water just stop someone’s age just like that? This was the conclusion I drew from my thoughts: Carlota Gentina was a bird, of the type that lose their voice in a headwind.