Читать книгу The Accidental Mayor - Michael Beaumont - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

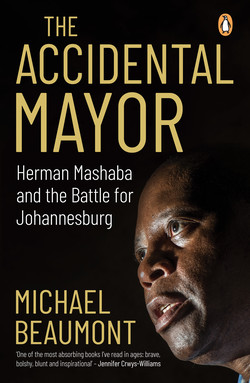

The accidental mayor

The 2016 local government elections were a watershed in South African politics. At the time, no opposition party held power in any of the country’s metropolitan municipalities outside of the Western Cape, where the Democratic Alliance governed the City of Cape Town as well as the province. But the ruling African National Congress (ANC) had become mired in scandal as allegations emerged during the first half of 2016 about corruption and state capture involving President Jacob Zuma, senior ANC politicians and the now-infamous Gupta family. Seeing their opportunity, the opposition set its sights on Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay.

The DA realised the importance of choosing the right person to stand as their mayoral candidate in the City of Johannesburg. It was going to require someone special to deliver that crucial municipality. Various names had been bandied about, but the one that stood out was Herman Mashaba. Through his business achievements, Herman Mashaba was already a brand.

Mashaba was not a politician. His entry into politics came late, at the age of 55, when he realised that being an armchair critic of the ANC’s failure wasn’t going to change anything.

He had always been open about his relationship with the ANC in the early days of democracy. He had thought a peaceful transition would be impossible and was overwhelmed by the miraculous moment of 1994. He believed there would be an explosion of entrepreneurship and growth in South Africa. How could there not, when the crippling oppression of apartheid had been lifted? Instead he witnessed a culture of patronage and government dependency set in. Rather than a thriving small-business sector, hand-selected tenderpreneurs benefited while the majority of entrepreneurs languished in a sea of red tape and bureaucracy, courtesy of a government beholden to organised labour in exchange for political support.

His hopes for the country were gradually replaced by the realities of HIV/AIDs denialism, quiet diplomacy with Zimbabwe, cadre deployment and rampant corruption. In the business circles in which he operated, Mashaba witnessed how the practices of tenderpreneurship, kickbacks and the selective and narrow application of black economic empowerment (BEE) took place at the expense of broad empowerment.

He publicly joined the DA in 2014, following a commitment to do so if the ANC was not brought under 60 per cent in those elections. He also wanted to show black South Africans that, in a democracy, loyalty to the ANC must not be unconditional and that a failing government must be replaced by another to be held similarly accountable by the people.

Born in 1959 in the small rural village of GaRamotse, Hammanskraal, in the north of Pretoria, Mashaba was one of six children. His father passed away when he was two, and his mother worked as a domestic worker in Johannesburg. He and his sisters were left to fend for themselves, often having to steal firewood and water to survive.

Before becoming mayor, Mashaba had worked only two salaried jobs in his life. He worked for seven months at a Spar distribution centre in Pretoria, and for 23 months at Motani Industries.

He met his wife, Connie, in 1978, when he and his friends visited a nearby girls’ school that was hosting a beauty contest. Connie won the contest, and she caught his eye. Mashaba felt that if he was to be successful in business he needed to settle down and get married. He and Connie tied the knot four years later.

From there, Herman and Connie Mashaba started the hair-care product range, Black Like Me. He secured a loan of R30 000 from Walter Dube, a pioneering industrialist in the black community, and partnered with a white Afrikaner from Boksburg named Johan Kriel. Over the years this partnership became a friendship and the Mashabas and their children would visit the Kriels’ farm, much to the ire of their neighbours in the late 1980s. Out of the boot of his blue 1982 Toyota Corolla, a business empire was built in the darkest days of apartheid oppression. As a testament to Mashaba’s enduring will to succeed, that car had to be serviced every month because of the mileage it racked up for the business. It paid off, and by 1997, when they sold Black Like Me, Herman and Connie Mashaba had built it into the foremost brand in black hair-care in South Africa.

Mashaba served as the chairperson of both the Free Market Foundation and the Institute of Directors in Southern Africa. He successfully tackled organised labour, challenging their efforts to extend collective agreements that would have hampered the growth of small businesses.

It took some convincing and much arm-twisting by DA stalwarts such as Mike Moriarty, John Moodey, Mmusi Maimane and Helen Zille to get Mashaba to stand as mayor. In fact, it bordered on coercion at times. So reluctant was he that he boarded a plane to the United States, at his own expense, to convince Lindiwe Mazibuko to stand as the party’s mayoral candidate. She declined, and Mashaba was forced to return home facing the prospect of a thoroughly undesirable job. There were two factors that ultimately convinced him to stand. The first was his strong sense of patriotism, in which the DA found their leverage. The second, ironically, was President Jacob Zuma.

On 9 December 2015, Zuma fired his respected minister of finance, Nhlanhla Nene. Apparently Nene wasn’t backing the president’s plans for a R1-trillion nuclear deal, which was shrouded with the familiar dark clouds of corruption. In Nene’s place, Zuma appointed Des van Rooyen, whose only claim to fame was being a failed mayor of an obscure West Rand municipality in Gauteng. Within 48 hours of the announcement, over R500 billion was wiped off the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Most of the losses were from pension funds. When public pressure mounted against Van Rooyen’s appointment, Zuma was forced to replace him, naming old hand Pravin Gordhan as his successor. South Africans sat bewildered by the fact that we’d had three different finance ministers within four days.

Incensed by Zuma’s actions, Mashaba threw his hat into the ring to be the DA’s mayoral candidate in Johannesburg. His greatest cause in life was now to unseat the ANC.

On Saturday 16 January 2016, after the DA’s electoral college, Mashaba was announced as their mayoral candidate for Johannesburg. On that same day, he resigned from his many business interests.

The DA’s campaign for the local government elections was already well under way when the mayoral candidates were announced. I was in charge of the campaign in Gauteng, overseeing a massive operation, coordinating 10 municipal campaigns run with thousands of volunteers. I had been managing provincial campaigns in the DA since 2009, starting in KwaZulu-Natal and then in Gauteng from 2011.

We knew it was going to be close, especially in Tshwane, Johannesburg and Mogale City in the West Rand. The ruling ANC’s support base had been rendered apathetic by the crippling years of the Zuma era, and the ANC metro governments had become detached, complacent and ineffective.

This was also the first election in which a new party had not entered the electoral race, enjoying all the Cinderella-type media coverage that goes with it. In 2009 it was the Congress of the People (COPE), which so-called experts forecast to become the future official opposition. In 2011, in KwaZulu-Natal, it was the National Freedom Party (NFP), which appeared to be an ANC-sponsored vehicle to unseat the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) in many municipalities. And in 2014 it was Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). Each time, the media’s attention swung towards these new start-ups, forcing us to do more just to stay on track.

The 2016 campaign in Gauteng stretched every structure to the limit. Recognising the breakthrough potential, the party poured enormous resources into the province. What had once been a big-enough event was now seen as a small gathering. Previously sufficient quantities of posters, leaflets and T-shirts were soon overshadowed by deliveries on fleets of tri-axle trucks. Makeshift local canvassing operations turned into town-hall-sized rooms abuzz all day and night with callers working the lines. A massive workforce of 20000 volunteers knocked on more than one million doors, engaging voters on our key messaging. It was a campaign that, by any measure, dwarfed all others.

There were five mayoral campaigns in Gauteng, each operating off a punishing grid of four to five events per day. All these campaigns were headlined by candidates of political breeding, conditioned by years of political experience, manicured into speech-making, vote-winning machines. All except Mashaba. In Tshwane we had Solly Msimanga, in Ekurhuleni we had Ghaleb Cachalia, in Midvaal it was incumbent mayor Bongani Baloyi and in Emfuleni we had Kingsol Chabalala.

Mashaba began every speech by saying that he was not a politician and never wanted to be one, but that he was standing out of a responsibility to serve the people of Johannesburg. His interviews left many in the party campaign structures grinding their teeth. None more so than when he was asked why poor people should vote for such a wealthy man. ‘Well, at least those people will know that I do not need to steal their money,’ he answered.

But there was something about the man that I perceived from an early stage of the campaign. He had a certain candidness, a fire and a stubborn drive to do what was right rather than what was expedient. These were qualities that I would come to understand and respect. Paradoxically, the very features that made Mashaba an unusual candidate, written off by the media and the commentariat at large, were those that would make him a popular mayor with the residents of Johannesburg.

Mashaba often shared with us his experiences on the campaign trail, of which there was no shortage, given that it involved four or five events a day for nearly seven months. Even years down the line, we were amazed by the detail of his campaign recollections and his ability to recount them when decisions had to be made.

He was greatly affected by his experiences on the ground in Johannesburg. It wasn’t that he was unaware of the deep-rooted inequality in the city before the campaign began; it was the extent to which he was confronted, day after day, by the staggering and stark lived realities of those who suffer, on the fringes of our society, under the legacy of the past and the indifference of the present.

The first event Mashaba attended after being announced as the DA mayoral candidate was on Saturday 23 January 2016 in Zandspruit. As became the norm across the city, Mashaba was struck by the deplorable conditions in which people lived. It was only by being confronted with it, face to face, that you could truly grasp the desperation. He took his daughter, Khensani, along with him and, to this day, she still speaks of it.

Mashaba had decided that he would not dance and sing and call people ‘comrade’. His was going to be a campaign of substance, about the issues that mattered to communities rather than politicians, focused on building a capable government that declared corruption public enemy number one. While speaking about his plans to the community of Zandspruit on a dilapidated soccer field, he began making the first of many connections to the ordinary, forgotten people of Johannesburg. Mashaba worked hard to address the mistrust that people in the townships and informal settlements had for the DA. What quickly emerged was a public appreciation for his authenticity and his ability to connect with people on a very personal level.

During one campaign stop in Alexandra, Mashaba met a young woman who he described as having a presence that would have been felt by the most powerful CEO if circumstances had placed her in a boardroom and not an informal settlement. The woman took the delegation to her shack, where they noted that she had no toilet facilities whatsoever. Mashaba asked her how she survived without a toilet, and her answer stuck with him. She said, ‘Over many years I have trained my body to only require a toilet at my place of work.’ When he told this story in his 2018 State of the City Address, the ANC councillors responded with laughter.

At another event in Kya Sands, Mashaba met a mother of three who cried about her circumstances and begged him to create jobs for people like her in Johannesburg. She spoke of how she was forced to sell her body to men for as little as five rand, and how they sometimes refused to pay her at all. She feared she was going to be killed. When he spoke later to the community, Mashaba asked what they could possibly have done to the ANC to deserve the cruelty of the conditions in which they lived.

In Eldorado Park, as in so many other areas, Mashaba was confronted by the extent of drug and substance abuse among the youth. A sense of hopelessness hung in the air in these communities, where drugs had destroyed families. On one occasion, a mother of an addict wept on Mashaba’s shoulder about her family having been ruined in their efforts to save their son from the grips of addiction. This never left him, and drove him to launch the first city-operated substance abuse facilities in Johannesburg’s history.

It became evident that Mashaba would stand out. Unlike politicians who were out of touch with the needs of the people they served, he would carry these experiences into every meeting, every engagement and every plan. That is the difference between someone who goes into politics with genuine intent to serve people and one who sees politics as a means to serve themselves.

The election took place on 3 August 2016. For the next two days, I was at the Independent Electoral Commission’s (IEC) national results centre in Pretoria with colleagues, watching as the numbers rolled in from polling stations around the country. We already had an idea of what would happen, thanks to thousands of our party agents who were reporting the results from the voting stations. But it’s different when you actually watch the numbers tick over in that results centre, in painstakingly slow fashion.

After going without sleep for three nights, we were now struck by a growing sense of wonder as it became clear that coalition governments could be on the cards in Johannesburg, Tshwane, Ekurhuleni and Mogale City. Some fell silent in amazement; others couldn’t stop talking with excitement. I stood still in cynical disbelief. I had experienced the unrealistic hopes of previous campaigns come crashing down on me when I was most vulnerable with exhaustion. This time, however, the weight of crushing disappointment never fell. We had brought the ANC down below 50 per cent in Tshwane (40 per cent), Johannesburg (44 per cent), Ekurhuleni and Mogale City (both 49 per cent), leaving the door wide open to coalitions.

The next two weeks were nerve-racking, as teams consisting of national and provincial leaders were sent into top-secret talks with potential partners. A deal was eventually concluded which formalised coalition arrangements between the DA, COPE, the IFP, the African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP), the United Democratic Movement (UDM) and the Freedom Front Plus (FF+).

In Tshwane, Johannesburg and Mogale City, we still needed the cooperation of the red berets of the EFF. Whether they could be counted upon to unseat the ANC, no one really knew. But the agonising wait came to an end when the commander in chief of the EFF, Julius Malema, held a press conference in Alexandra township on 17 August 2016. Here he announced that the DA were the ‘better devils’ and that his party would be installing DA-led coalition governments to unseat the ANC.

Then came the word ‘however’, a word you learn to dread in politics. It silenced all of us, short-circuiting our celebrations. The only sticking point for them was the idea of installing Mashaba as mayor in Johannesburg – clearly his lifelong advocacy of neoliberal capitalism was asking too much of the Fighters.

Over the next few days, party heavyweights scrambled to deal with Malema’s ‘however’. Could we really drop the man who had adorned 200 000 posters and 100 000 T-shirts and who had been the face of our campaign for the past seven months? Those most eager to be in power after years in opposition would have sacrificed their young for this moment. Equally, there were those who would have seen the entire world crumble before allowing another party to effectively choose our leaders.

Mashaba received news of the EFF’s position like every other South African – through the media. He was called and asked to comment before anyone in the DA had actually informed him. Mashaba was not fazed. His nonchalance did not arise from apathy or exhaustion, although the latter was certainly warranted. His response was simply that if he was the obstacle to unseating the ANC and taking over Johannesburg, then let the task fall to someone else. He didn’t need this in his life. He had no ambitions for a political career; he was a self-made multimillionaire who could pick up any cause he wished to support. He had been cajoled into standing for mayor out of concern for where South Africa was going under the ANC.

As it was, the party’s leadership remained strong and stared down the EFF. After all, who were they kidding? They had spent an entire campaign promising voters they would punish the ANC by unseating them. How could they backtrack on this now? At the end of the day, it was all a bluff by the EFF. They needed to be seen flexing their muscles on these new arrangements so as not to appear to be formally involved in them.

One by one the inaugural council meetings for the new political terms were held. In Tshwane, the DA’s Solly Msimanga was elected unopposed, resulting in rapturous celebrations. In Mogale City, Lynn Pannall followed suit as the next DA mayor. Finally came Johannesburg, with a 14-hour council meeting that went on late into the night. Former mayor Parks Tau of the ANC stood against Mashaba.

In the meeting, EFF councillors alleged that the ANC’s Dan Bovu, the former member of the mayoral committee (MMC) for housing, had approached them the night before, offering them R500 000 for each vote for Parks Tau, a claim that Bovu denied. This drove the meeting into chaos, with councillors of the DA, EFF and coalition parties wanting to show their ballots openly to the crowd to prove that they had voted for Mashaba and had not sold out. The ANC objected vociferously whenever this happened and the meeting came close to falling apart. One of the ANC councillors collapsed during the proceedings and tragically passed away later.

Present at this meeting was EFF deputy president Floyd Shivambu, whose presence was felt in the room. Within moments he was on the stage as an observer, overseeing proceedings and ensuring that his councillors adhered to the decision to back the multiparty coalition.

This experience taught me something that I came to appreciate about the EFF. No matter our differences, the truth is that they were straight shooters. If they said they were going to do something, they did it.

In the end, the votes were counted and Mashaba was announced as the new executive mayor of the City of Johannesburg, with 144 to 125 votes.

The next day I returned to my office to continue with my post-election analysis, which would inform the way forward in our preparations for the 2019 general election. That Friday afternoon, I received a phone call from Mayor Mashaba.

In his gruff voice he got straight to the point: he wanted me to be his chief of staff and to come and meet with him. I said it sounded like an amazing opportunity and asked him when he would like to meet. ‘Now,’ came the response, so I set off immediately.

As I drove across Johannesburg to Braamfontein during rush hour, I thought about what this meant.

The golden rule for any political principal in picking a chief of staff is to choose someone you can trust with your life and who complements your way of working. A chief of staff has to be able to draw on that trust in order to say what no one else has the nerve to say to a political leader.

Mashaba and I did not know each other well. We had engaged with one another during the campaign, so we’d met many times over the boardroom table. But I could not claim to have been close to him, because the nature of coordinating so many campaigns did not allow for overinvestment in any one particular candidate. The rapport and trust that exists between a principal and their chief of staff would have to be built from scratch. We were very different. He was a self-made man, who had defied the odds by overcoming abject poverty and prospering under an oppressive apartheid regime. I had grown up with a family in which I had received every opportunity a child could dream of in South Africa. He had 25 years of life experience on me, but I had 10 years’ experience in running political campaigns.

Our styles of working were dangerously similar. Typically, a relationship of this nature requires personalities that balance each other, but we shared a no-nonsense, highly driven and direct approach to getting the job done and believed that to make an omelette, a few eggs had to be broken. Another thing we indisputably had in common was that neither one of us had the faintest idea what we were getting into.

It was always going to be a strange combination, one that could either succeed in spectacular ways or fail even more spectacularly. After a brief meeting, we agreed that I would start the following day.

I went home to deliver the news to my fiancée, Mia, who a few months later would become my wife. There is nothing quite like being the chief of staff to the mayor of Johannesburg while planning a wedding at the same time.

The role of chief of staff is filled with complexities, to put it mildly. It requires the ability to understand every objective and every priority set out by the mayor, whether stated or unstated, and drive the strategy that achieves them. A successful chief of staff is able to translate the mayor’s values, strategic direction and principles and apply them to the myriad everyday decisions that have to be made. Because a chief of staff’s authority is purely an extension of the mayor’s, the price for getting it wrong is high for your credibility and future agency.

The chief of staff is also the conduit between the administration and key stakeholders and the mayor, ensuring that everyone knows what course has been set and receives the assurance and guidance they need to perform their functions.

To add to the complexity of the role, the chief of staff also has to manage the interface between the government and the party. During the campaign, Mashaba never had time to deal with petty internal politics, and this wouldn’t change now that he was in government. It fell to me to engage with a DA that reacted to the anxiety of the new governing arrangements by completely overcompensating. To say that the DA reacted calmly to the development that it was governing in three new metros overnight would not be true. The party demonstrated early on that it would involve itself in the smallest details, much to the annoyance of Mashaba, who did not appreciate micromanagement.

So it was clear from the start that the job of chief of staff was always going to be interesting. As the mayor’s most senior advisor, I had to learn to weigh my words and advice within the framework of the constitutional powers granted to him. We would be confronted daily by hundreds of decisions, all with high stakes in a delicate political environment and without the luxury of procrastination.

Requests for the mayor’s time would come in at a rate of around 20 per hour. I soon realised how important it was to protect Mashaba’s time, knowing that to address Johannesburg’s challenges, time would be our most precious commodity. Honouring even a fraction of these requests would translate into very little getting done. I quickly learnt the subtle art of gatekeeping, the ability to lock out the non-essential and ensure that every minute was spent optimally on the agenda. This made me supremely unpopular with just about everyone.

It was up to me to ensure that there was never a loss of focus on the mayor’s agenda. In a city of the size and complexity of Johannesburg, it is easy to be sidetracked by peripheral matters. Before you know it, your critical people are mired in meetings and work that does not further your priorities. A chief of staff must bring everyone back on point when necessary.

My biggest task by far would be to ensure that the strategic direction set by the multiparty government found expression in the plans and practices of a hostile administration. With 33000 employees appointed by the previous government, notorious for cadre deployment, we could safely assume that we wouldn’t get much help. In the best-case scenario we would be dealing with people who didn’t understand our agenda and direction. In the worst-case scenario there would be those actively seeking to undermine and sabotage us at every turn.

We were going to need something of an A-team to handle this task. Some politicians appoint weak people around them to flatter their egos, but this wasn’t Mashaba’s nature. We needed the best.

I brought in André Coetzee, a talented policy and research expert with communications experience, to be our director of policy and planning. He had run Solly Msimanga’s mayoral campaign in Tshwane and clearly had the intelligence to match his toughness. Simangaliso Shongwe, a stakeholder manager from Eskom’s difficult Kusile power station project, would handle our relationships with communities, labour and stakeholders.

Tony Taverna-Turisan had worked as a lawyer in the private sector and served in our communications operation in Parliament. He had replaced Willie Venter as Mashaba’s mayoral campaign manager on the eve of the election and the two had hit it off immediately. Tony was brought in as communications director the day before I arrived, and did a great job in those early months. In 2018, when we were battling to find a suitable director of legal services, Tony made the move and took up the essential mantle of legal advisor to the mayor. At that point, communications veteran Luyanda Mfeka came on as our new director of communications.

Lufuno Mashau was in the city’s governance department when we arrived. A brilliant financial mind with experience in the private sector, he was quickly roped in as financial advisor to discern the reality of the city’s financial position. Thabo Maisela, a former executive director of housing in the city with a ton of experience, assumed the role of inner city advisor. Saarah Salie, a highly skilled expert in performance management who had plied her trade in local government in the United Kingdom, became our director of monitoring and evaluation.

Each one left permanent or stable employment to take up fixed-term contracts in perhaps the most uncertain work environment around. If this government sank, they would sink with it. To their credit, they did not let this stand in their way. They were a dedicated team focused on making the most of this arrangement. There is something about people who come from an opposition background. They are hungry to achieve real change, they take nothing for granted and they have usually achieved much with very few resources – the exact qualities we needed.

With a good team and with my own experience in politics, I thought I was prepared for the mammoth task ahead. I mean, how much worse could it be than running provincial campaigns for a decade? To this day, I still laugh at my naivety.

It was the same with the job of mayor. Late one Friday evening, while discussing his diary for the following week, Mashaba turned to me and said: ‘Michael, you know, I built a business empire from nothing out of the boot of my car. This job makes that seem like a holiday.’