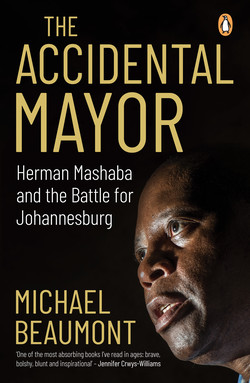

Читать книгу The Accidental Mayor - Michael Beaumont - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

The man

As Mashaba’s chief of staff, I gained insights into his character, and I came to understand how he managed to succeed in politics as a newcomer, not in spite of it but because of it.

A lot has been written about his rise from abject poverty in the dark days of apartheid to becoming one of South Africa’s most successful businessmen. He built an empire, not just in terms of business, but also in terms of vast networks and experience. His habit of speaking his mind and appearing unpolished in the political sense resulted in many commentators writing him off. I doubt it was the first time people had made that mistake. You must understand that by writing him off, you all but guarantee his stubborn success.

To say that Herman Mashaba is unconventional is an amusing understatement. The team I led in the mayor’s office was conventional, conditioned by years of experience in politics, communications, law, policy and performance management. Those years had institutionalised particular ways of thinking and benchmarking success. There were certain commonly accepted dos and don’ts that we took as unchallengeable truths. Mashaba, however, made it a habit to flip convention on its head, and I think he enjoyed doing it.

Most people look at a system and attempt to work within it to push its boundaries or alter its direction. They do this because it is more comfortable to operate within the known and attempt to influence change, even when the known is flawed. Mashaba is not one of these people. He is a disruptor. He looks at a system and sees how innovation and ingenuity can arise from disturbing the usual order of things. Ordinary and rational people seldom change the world because they see things as they are. It is the disruptors, who see the world as it should be, who often have the greatest impact.

Being a self-professed novice to politics, Mashaba approached the work of public service from a unique perspective. As noted before, politicians do not require advanced training in the ways that bomb disposal technicians, doctors and astronauts do. Politics requires a departure from the status quo, and for political leaders to approach each decision in good faith, with common sense and with the best interests of the people in mind. Common sense, despite its name, is not all that common in politics.

There was no place for political spin or expediency, both of which Mashaba outlawed in his first month in office. Over time we witnessed his approach at work in the city and how it affected decision-making, yielding positive results. This was particularly true in terms of managing relationships with coalition partners and the EFF. He would often disarm people by starting a meeting with the anecdote that he had studied political science at the University of the North for only a few months before the army shut it down. He would then convey to all present that ‘my knowledge of politics is very dangerous’, which, after a moment of stunned silence, would typically lead to laughter.

The next feature of the man that has to be understood is that he was not a career politician. He held no ambitions for higher office in either the DA or in government. He did not view being mayor of Johannesburg as a stepping stone to something greater; rather, he saw it as a privilege. He wanted to rescue South Africa from the ANC and he believed that fixing Johannesburg was the way to do it. He would often say: ‘When Johannesburg works, South Africa works.’ The reality was that he didn’t need the work. After about two weeks serving as mayor, Mashaba walked into my office, rather embarrassed, and asked: ‘Michael, do I get paid for this job?’ I couldn’t help but laugh. Can you imagine a South African politician accepting such responsibility without knowing the answer to that question?

Practically, this meant that Mashaba might have been the first mayor in South Africa who was not beholden to provincial or national government, or even to his own political party. This didn’t endear him to people in the DA and the other spheres of government, who were entirely unaccustomed to being unable to exert control. He was the accidental mayor. He had no aspirations that could be used to manipulate him.

In the run-up to the DA’s elective federal congress in 2017, an idea had begun to do the rounds in party circles, and among the EFF, that Mashaba should stand against Mmusi Maimane for federal leader. Several party members approached him to do so, but he wasn’t interested and batted away the suggestions. About two weeks before the congress, I was with him when he received a call from a prominent party leader who asked him whether it was true that he was standing for internal election. His response, genuinely, was to ask: ‘Is there a federal congress coming up?’

In 2018, party leaders again approached Mashaba, this time to enter the race to be the DA’s premier candidate for Gauteng in 2019. At the time he was indisputably the person with the highest name recognition and favourability in the province, and any prospect of taking Gauteng from the ANC would have been improved with Mashaba as the candidate. He flatly refused, saying that he had made a commitment to the people of Johannesburg and that they required a full-time, undistracted mayor. End of conversation.

In a similar vein and critical to Mashaba’s long and successful business career, and later his political career, was a firm belief that to succeed you can never be indebted. Once you owed someone something, you were in their pocket and beholden to them. It was a principle he applied every day as mayor of Johannesburg, where people were constantly attempting to ‘capture’ him in order to have him in their debt. Often, a meeting would finish and Mashaba would turn to me or one of our team and say: ‘Never let people compromise you. When that happens, they will own and control you.’

When engaging with audiences in his speeches, Mashaba would frequently depart from the script and begin sharing personal anecdotes. On one occasion, at a particularly formal event, he spoke about growing up without parents present in the home. In explaining how this affected a young boy, he described how he had ‘woken up one day to discover a part of my anatomy which was already awake’. After a moment of awkward silence the audience roared with laughter. On another occasion he spoke openly about smoking dagga as a teenager in the townships of Pretoria and realising there was a business opportunity there, until his mother put an end to that. Schooled in conventional politics, my team and I would kick into overdrive and ready ourselves for the expected fallout, but it never came. Audiences embraced him for his candidness, his relatability and his humanity – traits they no longer associated with politicians. But then, Mashaba refused to call himself a politician. He started every engagement by insisting that he was a public servant.

Mashaba is one of both the hardest and the kindest leaders I have ever met. When people failed, he would be forgiving if he believed they had operated in good faith. However, when he lost faith in someone’s intentions, he could be brutal. On a few occasions, the deserving recipients of his wrath ended up in my office, where I’d have to play the role of comforter, which was entirely out of character for me. The truth was that I had to ensure that their departure didn’t result in an ugly spat that would necessitate a PR war.