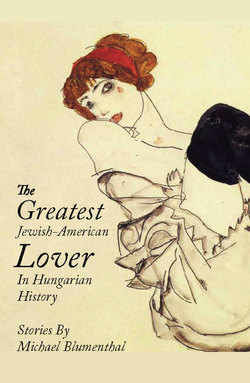

Читать книгу The Greatest Jewish-American Lover in Hungarian History - Michael Blumenthal - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSHE AND I

She is quintessentially French. I am, in the loosest sense of the word, American. She always feels cold. I am always hot. In the winter, even if it isn’t chilly, she does nothing but complain about how cold it is. Even in late spring, there are large, fertile fields of goose bumps on her thin, beautiful arms, and I have known her, even in the Middle East in late June, to wear a woolen sweater around the house, to sleep in a lamb’s wool camisole in August.

She speaks, since she doesn’t speak much, only one language well, though she seems to understand so much more than I do, even in the languages she doesn’t really speak. I, on the other hand, can make myself understood in several languages, yet have trouble focusing on the conversations of others.

She enjoys reading maps and navigating around in new places. I hate it, and quickly grow impatient and ornery. After a single afternoon in a foreign city, she will have mastered the public transportation system, be able to find her way to the centrum from the most desolate-seeming corners. I will get lost five meters from my own hotel, or—worse yet—a new apartment. She hates asking for directions, preferring to gaze patiently at a to-me-indecipherable map for many moments. When we get lost, I am quick to blame her. She blames no one, but busies herself looking for second-hand shops and fruit and vegetable markets in whatever neighborhood we are lost in.

She loves old architecture, curved surfaces, rummaging among the trinkets and memorabilia of other people’s lives at flea markets, the scent of flowers and herbs. I am always impatient to get where I’m going, missing virtually everything along the way. The only two things I’ve ever been able to love completely and unconditionally are my own disfigured face in the mirror and sitting at my desk making a kind of music exclusively with words . . . though I love my son, and sometimes her, in a different way, as well.

She loves travel, unfamiliar places, a sense of the unexpected. I dream of living always in one place, burning my passport, etching an address in stone upon my door post, running for mayor in some town I will never again move from.

I love to eat in restaurants—bad restaurants, good restaurants, even mediocre ones. She always wants to eat at home: fresh vegetables and better food, she claims, at a third the price. She hates the way I do the dishes and leave a mess after cooking. I like, on occasion, to do the dishes and cook, though I’m quite awful at the former, which I always do in too great a hurry, leaving all sorts of prints, smudges, and grease stains along the way.

She loves to watch a late movie—preferably a slow-moving, melancholic one of the French or Italian sort—and to have a glass of wine or two with dinner. I prefer rather superficial, fast-moving American films, fall asleep almost the second I enter the theatre for anything later than the 7:30 showing, and can drink, at most, a glass of white zinfandel in late afternoon.

She has little patience for, or interest in, pleasantries among strangers, preferring to restrict her circle of acquaintances to those she is truly intimate with. I enjoy talking to the garbage collector, the mailman, making small talk with the meter-reader and taxi driver. The greetings “How are you?” and “Have a nice day” do not cause me to rail against the superficiality of America and Americans.

She is shy; I am not. Occasionally, however, her shyness rubs off on me, or, alternatively—as in the case of landlords who are trying to take advantage of us or rabbis who are too adamantly in favor of circumcision—she loses her shyness and grows quite eloquent, even in English, her vocabulary suddenly expanding to include words like barbaric and philistine.

She has no respect for established authority, and thinks nothing of running out on student loans, disconnecting the electric meter, or not paying taxes. I, on the other hand, though I have the face of an anarchist, am afraid of established authority and tend, against my own better instincts, to respect it. As soon as I spot a police car in the rearview mirror, I assume I have done something terribly wrong and begin to contemplate spending the rest of my life in jail. She, on the other hand, smiles shyly at the police officer, who quickly folds up his notebook and goes back to his car.

She likes goat’s cheese, garlic, a good slice of pâté with a glass of red wine, tomatoes with fresh rosemary. I like sausages, raw meat, pizza, and gefilte fish with very sharp horseradish.

She claims that I am a Neanderthal when it comes to food, a barbaric American animal who will die young of high cholesterol, rancid oils, and pesticides. She is refined, has a sensitive palate and a nose so accurate it can tell the difference between day-old and two-day-old butter. When we lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, she spent many days in search of the perfect, vine-ripened tomato and just the right kind of basil for making pesto. She can’t stand, for example, pine nuts that are rancid. “Rancid,” in fact, is one of the English words she uses most frequently.

At the cinema she hates to sit too close to the screen, and—if we’re at home—refuses to watch movies on TV that are interrupted by commercials, claiming that it interferes with her “dream world.” I like to sit near the front of the theatre and tell jokes during the movie. I like almost any movie, as long as it is superficial enough not to disturb my worldview. She prefers dark, slow-moving, romantic tragedies, set to the music of Jacques Brel, which linger in her imagination for many days after, causing her to question, or reexamine, almost everything in her world. She remembers the names of films and actors, and prefers actresses who embody a kind of low-key sensuality and dark reserve. I adore those who are brazenly sexual and whore-like in their demeanor. If, for example, as in Roman Polanski’s Bitter Moon, there are two women, one of whom is subtly beautiful, sensual, and slightly tragic, the other who is vulgar, brazen, hedonistic, and rather shallow, it is always certain that she will prefer the first. I always prefer the second.

On those rare occasions when we’ve seen a film we both liked, she will, the next day—even the next month—remember every small detail of it: the weather in a particular scene, the shape of an awning, the way a blouse or a cloth napkin lay against the protagonist’s arm or lap. I, on the other hand, will remember nothing, not even the plot, as if some premature and obliterating dementia had overtaken me during the night. Somewhat sheep-faced, I will ask her to remind me what the movie was about, who was in it . . . on occasion, even, what it’s name was, all of which she will generously do, never even pausing to comment upon my infirmity.

Though I am rather smart about books and literature, it is the rare film in which I am even able to follow the plot line, much less unravel the mystery, so that, after we leave the theatre (assuming I haven’t fallen asleep), I will usually need her to explain to me exactly what happened, who was related to whom, and why, at the end, a photograph of one character’s daughter mysteriously showed up on the wall of a seemingly unrelated character’s living room. When she does, I am inevitably embarrassed about my simple-mindedness and lack of insight, a shortcoming she seems either oblivious to or willing to overlook.

I either love or hate people, and find myself utterly incapable of having any interest in those I am indifferent to. She, though often equally indifferent to the same people, always seeks to find something interesting and unique about them, a pursuit I have neither the time nor patience for. Something in even the most uninspiring person arouses, if not her conversation, then at least her curiosity, and—once she has been engaged with someone in any way—she retains a certain ongoing loyalty to them I can neither relate to or comprehend. Though far less extroverted than I am, she will carry on a correspondence with any number of people, in all sorts of countries, and keeps a list in her address book of all the birthdays of everyone she has ever known and liked.

I consider every crisis a catastrophe, and will begin to fidget nervously and despondently whenever I am confronted with a late train, a rescheduled flight, or an incompetent waitperson. She considers each of these events a hidden opportunity, a portent from the gods, yet another manifestation of the world’s independence and revivifying fickleness.

Though I have somehow been appointed the “breadwinner” of our family, I am extremely lazy: my favorite activity, as Freud said of poets, is daydreaming, my buttocks wedged firmly in a chair. She is never idle, raising domesticity to an art form, a Buddhist perfection in every ironed crease.

Being a devotee of Bishop Berkeley’s formulation to the effect that, if you can’t see it, it isn’t there, I prefer neatness to cleanliness: My idea of housecleaning is to sweep the large dust balls under the bed, stuff plastic and paper bags sloppily into a kitchen cabinet, cover the bed hurriedly with a creased down comforter, cram my underwear (freely mingling with socks) into a dresser drawer. She is almost maniacally clean, sniffing each of my shirts and socks daily to make sure they don’t need to be washed, vacuuming in corners, changing the pillowcases and sheets with the regularity of tides.

I like to buy cheap things, particularly clothes, frequently, wearing them until they fray or lose their shape, and then cart them from place to place without ever wearing them again. One of the things she seems to enjoy most is to go through my clothes closets, reminding me of all the cheap items I bought and never wore, or which I have worn once, washed, and which are now “totally useless.” She buys clothes almost never, but always things of good quality, preferring to wear the same few things (always immaculately clean) time and time again.

I fancy myself a great dancer and a sex object. She thinks of herself as physically awkward and more sensual than sexy. I can type like a madman and, albeit reluctantly, use a computer. She considers a keyboard a frightful artifact.

I like to drive. She likes to navigate. On those few occasions on which she drives our car, I nag her relentlessly about shifting at the wrong speeds, or squeezing too hard on the brakes. When she navigates and we begin to lose our way, I immediately become so ornery and hostile that, on at least one occasion in Budapest, she threatened to get out of the car and go home on her own. In countries known for their dangerous drivers, she insists I do all the driving, an affirmation of my manhood I accept reluctantly, though I don’t object to being in control.

I am the kind of person who can do many things at once, most of them rather imperfectly. She does only one thing at a time, but always with a sense of perfection.

I like to cook without recipes, freely mixing Marsala wine, mustard, artichoke hearts, candied ginger, maple syrup, and plums, hoping something capable of being digested will emerge. She always uses a recipe—except for things she has made before—but everything she makes is successful and delicious.

I would have been a rock star, or a concert pianist—or perhaps, even, the proprietor of an illicit sex club—had I felt freer to follow my lyrical and immoral heart’s calling. She would have been a sister in a Carmelite Monastery, or a gardener.

She is an enthusiastic and natural mother. I am a reluctant father.

She could have been many things, all of them having something to do with taking care of others or using her hands: a nurse, a dentist, a carpenter, a potter, a refinisher of furniture, a restorer of antiquarian books. I could, though I like to imagine otherwise, probably have done only the one thing I am doing now: putting words to paper.

I like to live part of my life in the if-but-only mode of wishful thinking and fantastical alternatives. She accepts the life life has given her as her one possible destiny, without complaining.

She doesn’t like to think of money—in fact, her refusal to think about it has, on occasion, gotten her (and me!) into heaps of trouble. I, while I don’t like to think of it either, am usually left with the unpoetic task of having to worry about it. Since I have been with her, in fact, hardly a day has passed without thinking of it . . . almost constantly. She, on the other hand, worries about many other unpoetic tasks in our lives that have nothing at all to do with money.

I can imitate people from many countries, and with many different accents. She is too much herself to imitate anyone.

I like to have some kind of music playing whenever I am not reading or working. She usually prefers silence, or only to have music on when she is actually listening to it.

I will continue to eat even when I am no longer hungry, just for the pleasure of it. She eats only as much as satisfies her hunger on any occasion. I abhor all forms of table manners, eating with my fingers, chewing with my mouth open, taking food freely from others’ plates, licking my fingers at the table, stuffing my mouth with large quantities, burping and passing gas. She never eats before being seated at the table, waits for everyone else to do likewise, chews only small morsels at a time, and eats so slowly, and with such deliberate pleasure, that I have usually finished what is on my plate well before she is actually seated. Only twice in our eight years together have I observed her passing gas. Burping, never.

As soon as I make a decision, I immediately, and relentlessly, tilt toward wanting the other alternative. She immediately accepts, and begins to implement, any decision she has made. She often says that I am a neurotic and “special” kind of person; she feels that, living with me, this kind of behavior is the “statue quo.” Occasionally, when I am in one of my periods of manic reconsideration, she smiles slightly in her slightly smiling French way, as if to say, “Oy vey, what a case I am married to.”

I like to eat on the street—frequently, and mostly greasy and unhealthy foods—which accounts for the fact that most of my clothing have grease and/or coffee stains on them, souvenirs of my animalistic habits she claims American washing machines are incapable of eradicating. Most of all, I like to devour greasy Hungarian sausages at stand-up counters in Budapest. She likes to eat only “à table,” quietly, savoring every morsel of, say, pâté with, preferably, a glass of red wine. Among the tastes in life I can truly not abide are pasteque, fennel, and every form of anise, all of which she has rather an affection for.

I am often angry at others, friends, foes, and family alike, and like to hold, and nurse, these angers for as long as is humanly possible, until I can almost feel them eating at my liver, like an earthquake with numerous, sustained aftershocks. She is incapable of sustained anger or hostility and would, I believe, (perhaps already has) forgive me the most egregious deeds and betrayals, an attitude I have no desire to test to its limits. Even in her case, I like to remind her as often as possible of the ways she has disappointed and betrayed me. She, on the other hand, rarely mentions my betrayals and weaknesses.

I never cry, even when I am truly unhappy, yet I have a tendency to grow teary-eyed whenever an athlete experiences some major triumph, or after the last out of the World Series, when the players all rush to the mound and hug each other. She cries easily, even at sentimental movies whose pandering to sentimental feelings she despises.

I will take any kind of pill or medicine anyone recommends in order to relieve pain and discomfort. She prefers “natural” remedies. Although I am not terribly Jewish by religious conviction, I wanted to have our son circumcised when he was born. She felt it to be a pagan ritual tantamount to permanent disfigurement, and began assembling propaganda from various anti-circumcision organizations around the country depicting vast armadas of mutilated children with heavily bandaged penises. She won. She usually wins.

I think she is beautiful, but too thin, and am constantly after her to try and gain weight. She thinks she is less beautiful than I do, but comments frequently about her “beautiful arms.” When she was younger, in California, she wore her hair very short and looked like a kind of postmodern French punktress on her way to the wrong discotheque. Now, I think, she is much more beautiful and womanly, and, like I am, a bit older.

When we met in Ecuador, she had rather gray hair and was wearing purple nylon pants and a yellow sweatshirt. She seemed, at first, more interested in reading her mail than in talking to me, a fact that I soon realized was due more to her shyness—and her passion for her mail—than to lack of interest in me. On the two-hour bus ride between Quito and Otavalo, across the Equator, I slowly began to realize that she was quite beautiful, in an undemonstrative sort of way, and that night, as I way of getting myself into her room and closer to her bed in the hotel where she, her female traveling companion and I were staying, I planned to borrow her toothpaste. But she wasn’t, I discovered, as shy as she seemed, and it turned out I didn’t need to do that. The next morning I remember her companion bringing two glasses of fresh-squeezed orange juice to the room, along with coffee, and then our walking, hand in hand, above the town of Otavalo, where we finally sat in a small restaurant and her friend Annick took our picture. I looked very happy in the photo, though not too handsome. She looked happy too, and quite lovely.

We stayed in several very lovely, and inexpensive, small Ecuadorian hotels during those days, and I remember, not even a week after not having to borrow her toothpaste, looking down at her one night (or was it afternoon?) and saying, “I think I love you.” “I think I love you too, Gringo,” she replied. She used to call me “Gringo” in those days.

I remember talking to her an awful lot back then, and thinking to myself how attentively, and compassionately, she always listened. I myself am not such a good listener, except on occasion, so that—along with the sweet way she always said “uh huh, uh huh . . .” and “yes . . . yes” when I was telling her a story—it made a real impression on me. Back then, I don’t remember her being nearly as cold, or quite as thin . . . but, then again, we were in love and in Ecuador.

Sometimes, now, when I realize we have been together for more than eight years and have a seven-year-old son, I think that this is one of the major miracles of my life . . . and I’m sure she does also. I was so romantic then, that night in Otavalo, and so was she when, hardly a week later, she got on a plane from Quito to the United States and followed me to Boston. I remember her calling me, as we had planned, but suddenly having a sense that the call wasn’t quite long distance. When she told me she was standing at a pay telephone across the street at Porter Square, I ran down the stairs, not even bothering to button my shirt or pull up my zipper, and took her into my arms and carried her halfway up to my fourth-floor, rent-controlled apartment.

I was stronger in those days, and healthier, and so, maybe, was she. We were not so young, but very much in love, and there was a scent of laundry, somehow, wafting through my windows as we made love, on a mattress located on my study floor, for the first time in the United States of America.

Now, as I write this, I am sitting in Israel, and we will soon be in Paris, then in Provence, and then back in the United States of America, the only country whose language I have truly mastered. I no longer live in that rent-controlled apartment and that mattress, I am quite sure, is no longer on the floor. She is still beautiful, though—perhaps even more so—with her knowing eyes and beautiful smile and lovely French voice, and she is still, as a friend of mine once described her, “une chouette”: an owl.