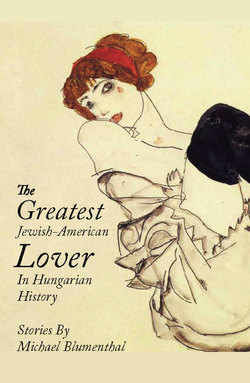

Читать книгу The Greatest Jewish-American Lover in Hungarian History - Michael Blumenthal - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE DEATH OF FEKETE

When Aunt Etus’s son’s dog, Bori, bit Kormány Lajos in his right leg at the vineyards of Szent György Hill, it seemed only logical to the bored and unemployed men of the village—Gyula, Roland, Feri, and Kormány himself—that the dog had to be shot.

Because Etus’s son, Árpi, was a large man, however, known to have a bad temper, especially when drunk, self-preservation dictated a wiser course: namely, to shoot Etus’s small puli, Fekete, instead. So the four men, after borrowing Uncle Dönci’s old Hungarian World War I police rifle, grabbed the “innocent looking dog from Etus’s front yard” by the ears, bound him into an oversized potato sack, and took him up into the back of Gyula’s winemaking house, where they fired a round of six cartridges into the helpless animal, who yelped and twitched when the first bullet entered his abdomen, and then moved no more.

The dog, to be sure, was quite dead after the shooting, and it seemed to many a gratuitous bit of cruelty when the body, blown into small bits, was left on Etus’s doorstep. Though everyone in the village realized that Kormány had been involved, blame for the heinous event somehow began to center around the illiterate and partially deaf Feri, who had, for years, been spending his days, from late morning to well after midnight, ensconced at the local pub, and whose appetite for cheap pálinka followed by large glasses of Balaton Olaszrizling was as extensive as his vocabulary was small.

It was not that Feri was considered cruel: he was universally acknowledged, rather, to be simply stupid, and like most stupid men, easily prone to the role of follower. Moreover, it had long been suspected that Roland and Gyula, the more robust and mischievous of the unemployed quartet, exerted an undue influence over the hapless lad, who—much to Kormány’s embarrassment—was a distant cousin of his as well. Feri’s mental infirmities, it had been suspected, were the logical by-product of the too frequent marriages and procreations among cousins and near-cousins that village life inevitably spawned.

In many ways the most innocent of the foursome, Feri spent his increasingly scarce hours away from the pub collecting, and meticulously inventorying, old Elvis Presley and Beatles albums, the one mental activity his limited intelligence could apparently master. Always dressed, no matter how hot or dry the season, in tattered brown leather overalls, a pair of green, knee-high rubber boots known as gumi csizma, a black-and-red woolen ski cap that looked as if it had originally been skied in during the reign of Kaiser Franz Joseph, and a New York Yankees baseball cap, he was known—for the village’s annual Szent Lörinc Festival dance following the soccer match between Hegymagas and neighboring Káptalantóti—to treat himself to a much-welcomed shower and shave, after which he would don the dark gray wool suit that had once been his father’s.

Feri senior, the former village postmaster, had been run over by a mule-drawn Gypsy cart ten years earlier while staggering home from his mistress’s house in neighboring Raposka. His father’s death and the suicide of his retarded younger sister, which followed almost immediately upon it, had driven the boy (everyone referred to him as “the boy,” though he was nearly forty) only deeper into the inertia of village life, so that he was now as much a fixture on the wooden bench outside the Italbolt as was the pub’s bench itself, rousing himself into action only when some sort of entertainment—such as the soccer match or, everyone now speculated, the shooting of Etus’s dog—was offered in its place.

The bite on Kormány Lajos’s leg, in fact, had been a bad one, and it was the universal sentiment that Kormány—a frequent trespasser on, and pilferer from, the largely unoccupied vineyard houses—had probably trespassed one too many times on Árpi’s three grape-filled hectares, thus becoming the object of Bori’s, and his master’s, proprietary instincts.

Etus, on the other hand, was the best loved of the village’s large group of widowed nénis, a woman of boundless generosity and good will who—in addition to being the traditional winner of the annual fish soup contest each August—was known to wander from house to house, distributing ears of corn and the small unsweetened round cakes known as pogácsa to the children and the bedridden, her tattered and (to the dismay of all who loved her) foul-smelling apron tied around her neck and a good word for everyone on her lips.

Etus had adopted Fekete several years earlier, when the dog followed her home on her bicycle from the market in Tapolca. She could still ride long distances in those days, and the two of them had been virtually inseparable ever since, the dog following loyally at Etus’s feet as she made her way from the vineyard to the pub on her various missions of mercy. Fekete, a small, affectionate, though somewhat yappy animal, was hardly prone to outbreaks of aggressiveness unless severely provoked or, it turned out, finding itself in Árpi’s immediate vicinity, where—much like his more formidable cousin Bori—he experienced a kind of transformation of personality consonant with Árpi’s ornery and frequently inebriated ways.

On the day of the incident that led to Fekete’s death, Kormány, having downed one too many pálinkas for breakfast, had apparently wandered onto the perimeters of Árpi’s vineyard as he set off into the hills. The two men had had a history of altercations, large and small, dating back some ten years earlier when Kormány had sold Árpi a supposedly reconditioned Trabant station wagon for 20,000 forints, only to have the engine utter its last gasp before its new owner could even make it to Tapolca for a new front fender.

On the morning in question Árpi, suffering from a headache and hangover, was not at all disappointed to see Kormány staggering toward him and eagerly sent Bori, chomping at the bit, off in the trespasser’s direction. It was only seconds later that a howl reverberated throughout the vineyards, as the dog’s sharp canine teeth tore through Kormány’s three-generation-old overalls and nestled in his right leg, penetrating all the way through the flesh and into the fibula.

Kormány’s wife, a nurse in the local hospital, seemed to take a certain private glee in her husband’s injury. Nonetheless, she was reluctantly summoned to bandage the wound and check the dog for rabies, her negative verdict concerning which did little to alleviate either Kormány’s anger, or his pain.

Kormány, in fact, had never been terribly fond of Etus, having long felt that her virtual lock on the annual fish soup prize was one of the reasons for his own mother’s premature death from a cardiac infarction—he described it as a “fish-soup-broken heart”—two years earlier. The elder Aunt Kormány’s concoction, her son knew, had been far superior to Etus’s soup, and it was only the sentimental admiration in which Etus and her family were held—as contrasted with the distance most of the villagers kept from the legendarily drunken Kormány clan—that, he was certain, explained such an undeserved monopoly.

Gyula, the eldest of the foursome, had once made what seemed a reasonable living as a go-between in the summer rental market for vineyard houses to Austrian tourists. But he had fallen victim, both to his increasing penchant for women and drink, and his inability to accommodate his rather lackadaisical spirit to the realities of the new market economy. Each passing year found him spending more and more of his time at the Italbolt in the company of Roland, a former carpenter who had severed his right hand with a chainsaw while drunk three years earlier, and less and less time at the “business office”—a three-legged kitchen table supported by bricks, on top of which was perched a 1928 maroon Continental typewriter—he had set up in his widowed mother’s pantry.

So—when news of Kormány Lajos’s wounding spread from the vineyard to the ABC store, and then from the ABC store to the pub—it took little in the way of urging for the wounded victim to recruit Gyula and Roland to the righteousness of his quest for vengeance against relatively affluent, and well-respected, Etus and her clan.

Etus herself, who spent much of her time baking cheese strudel to be sold at the beach in nearby Szigliget, was hardly a vindictive sort, and—wounded as she was by the violent death of her beloved puli—would have preferred to let the incident pass and get on with her acts of charity and culinary generosity. Nor was Árpi, whose drinking and carousing Etus was convinced had caused the premature death of his father some twenty years earlier, easily aroused from his usual, less than fully conscious, state on his mother’s behalf.

But the writer Fischer and the sculptor, Kepes, both of whose families had been longtime friends of Etus’s, felt particularly aggrieved by Fekete’s death and the consigning of Etus to a kind of second widowhood. The day after the killing, they took it upon themselves to pay a visit to the Mayor, Horvath János, to inquire as to what justice could be rendered the cold-blooded killers of Etus’s dog.

Horvath János was a firm believer in maintaining the village’s veneer of tranquility at all costs. He had for years been witness to the “revolving door” of trying to tame the impulses of the troublesome quartet—periodic short-term jailings in nearby Tapolca, accompanied by repeated reprimands by both himself and the local police chief—none of which had resulted in even the slightest change in their behavior.

“Kedves barátaim,” he addressed Fischer and Kepes as he invited them into his winemaking house on Szent György hill. “My dear friends…There is really nothing I can do about this matter. It is, after all, only a dog, and not a human being, that has been put to death.”

“Yes, of course, it’s a dog,” Fischer, not one to be easily intimidated, replied, “but it’s a widow’s dog—a widow, I might add, who has been a source of kindness in this village for more than sixty years—and I don’t think we should merely stand by and do nothing when poor Etus’s companion—an innocent dog, at that—is murdered in cold blood by four no-good drunkards.”

“I agree,” Kepes, who rarely left the confines of his newly converted studio, even to go to the Lake, and had been dragged along by Fischer, concurred. “It is not good for the village’s reputation,” he added, appealing to an area he knew to be high on the list of the Mayor’s concerns, “for the dogs of our widows to be randomly slaughtered.”

Kepes’s appeal to Hegymagas’s public relations seemed to have a momentary impact on the Mayor, who paused to remove the glass borlopó he had been using to fill a bottle of Chardonnay from a wooden cask from his lips.

“Yes,” he said, “I suppose you’re right—it’s not good for the village’s image. But, on the other hand, we must remember,” he was quick to add, immediately returning to his avocation, “that we are not Keszthely . . . it is hardly as if droves of German and Austrian tourists in search of cheap dental care will be discouraged from coming here by the death of a dog. Why, we don’t even have a dentist!”

“I am not talking about public relations,” Fischer, a former samizdat writer and democratic resistance leader who was quick to lapse into cosmopolitan-style abstractions, was turning rather red. “I am talking about justice for poor Etus and her dog.”

The Mayor, a member of the rather right-wing Smallholder’s Party that was currently part of the governing coalition, had never been terribly fond of Fischer. He looked up from his more domestic duties, removing the borlopó once again from between his lips.

“Kedves barátom,” he said, addressing the writer with a combination of feigned respect and ill-disguised disdain, “I am afraid that such appeals to higher authorities carry far more weight in Budapest than here in our little village. I am merely trying, as best I can, to keep the peace.”

A slight expression of distaste began to make its way onto Fischer’s face as he paused to take a sip of the Mayor’s rather mediocre Sauvignon Blanc. “It is not,” he replied, “a ‘higher authority’ we are appealing to . . . it is your authority.”

“And that authority, I am afraid, kedves Fischer úr,” the Mayor rejoined, “is severely limited by the realities of our village life.”

Disgusted by what he perceived to be the Mayor’s condescending and parochial, small-town attitude, Fischer, followed obediently by Kepes, turned on his heels and strode out the door of the Mayor’s cottage. “In that case,” he turned to address the Mayor once more as the twosome headed back down the hill, “we will simply have to take justice for poor Etus into our own hands.”

***

Hardly three days later, Kormány Lajos’s prize sheep, a dark-haired animal by the name of Levente, was found hanging from a large oak just behind the stream that separated the village from neighboring Raposka.

The very next day, one of Hegymagas’s most eloquent citizens, the thirty-four-year-old parrot, Attila, was found dead on the floor of his wooden cage beside the kitchen table in Gyula’s mother’s kitchen. Not even the most loving ministrations of Kormány Lajos’s wife could revive the bird—a gift from Gyula’s grandmother shortly after her emigration to Chile in 1956—who had startled, and endeared itself to, even Hegymagas’s most patriotic citizens with its ability to pronounce the nearly unpronounceable Hungarian word for drugstore—gyógyszertár.

But it was only when, finally, Feri’s antique gumi csizma were found, the following week, melted into a foul-smelling rubbery blob in the stone fireplace just below Árpi’s hillside hectares, and Roland’s prosthetic hand was discovered, the following day, to have been stolen from his bedside table, that the Mayor decided the time had come to involve himself personally in the increasingly anarchic system of law and order that was threatening to engulf the village.

Knocking on the door of Fischer’s two-story village house late one afternoon, Horvath, emboldened by a half bottle of plum pálinka, greeted the writer with the habitual Hungarian kiss on each cheek.

“Jó napot kivánok, kedves barátaim,” the Mayor announced, stepping over the threshold into the kitchen and adopting what was, vis à vis Fischer, an unusually amiable tone. “Good day.”

“Good day, kedves Polgármester úr,” Fischer sensed that something had gone a bit awry, and responded politely but guardedly. “Come in and have a seat.”

The Mayor, deciding to take advantage of the momentary air of conviviality that had entered his relationship with Fischer, cut right to the heart of the matter.

“It seems,” he said, exhaling deeply and moving to light a cigarette, “that certain citizens of our village have decided to take justice into their own hands with regard Etus néni’s dog . . . And I am not,” he continued before Fischer could get a word in by way of response, “very happy about it.”

Fischer was just about to undergo a radical change of mood and tear into the Mayor concerning his unhappiness with the Hegymagasian system of justice, when there was a knock on the door and Etus herself entered the Fischer’s kitchen. Beneath her right arm were six ears of freshly cut corn and, in her left hand, a plastic bag containing several dozen assorted plain and cheese pogácsák.

“Kedves Polgármester,” she gave the Mayor a kiss on both cheeks. “Kedves barátaim,” she likewise greeted Fischer, simultaneously mouthing the Hungarian words for good day. “Jó napot kivánok.”

“How lovely to see you, Etus néni,” Fischer, ever the gentleman among women, softly kissed his elderly neighbor’s hand. “Kezit csókolom.”

“I am not good,” Etus, placing her two loads on the Pilinskzys’ kitchen table, replied. “Not good at all.” To Fischer’s surprise, and the Mayor’s embarrassment, a small flotilla of tears suddenly began tumbling down Etus’s cheeks.

“It is not right, what is happening in our small village, on account of my poor little Fekete, and I want for everyone—I repeat, everyone—to please stop behaving in this way, so that we can all live together again in peace.”

No sooner had the word “peace” echoed into the room from poor Etus’s lips, however, but a tremendous splattering of shattered glass could be heard coming from Fischer’s backyard. Running out into the garden, tear-stricken Etus and her reeking apron just behind them, the Mayor and Fischer were confronted with the heartrending sight of Fischer’s once-intact clerestory window scattered all over the lawn in a million glistening small fragments. Inside, nestled tranquilly between Fischer’s hirsute begonias and his upturned prize oleander bush, was a large gray stone with the words csunya disznók!— ugly pigs!—painted on it in a pigment all too closely resembling pig’s blood.

“Kedves Isten!” muttered Etus, tears still running down her cheek. “Dear God, what will we do now?”

“We do,” Fischer, never one to linger without a solution, replied, “the only thing any civilized village would do—we drive the bastards out of town.”

Fischer’s reveries of prairie justice, however, were quickly interrupted by a terrible howling sound, like that of a dog with its leg caught in a trap, coming from somewhere across Széchenyi út, followed by the sound of rubber being left on the dusty street, as a car accelerated out of town.

“Now, what the hell is that?” the Mayor cried out, running out into the street, where he was met by the sight of a large pig—from all appearances, Árpi’s pet pig Kadar—dragging its bloody, partially severed tail down the street and howling for all it was worth. Through the dusty aftermath of what had just taken place, the Mayor was fairly sure he could still make out the contours of a rusted yellow Trabant, exactly like Gyula’s, leaving yet another patch of rubber on the road as it turned right and headed toward Tapolca.

***

An eerie, unnatural quiet permeated the village over the next several days—a quiet more characteristic of the short, wintry days of February than the busy tourist season of mid-July. Even the ABC store, site of the ritual daily lineup for fresh bread and cottage cheese, began to take on the lonely, abandoned feeling of an athletic stadium during the off-season. Etus, Terika néni and Vera néni, the three widows whose pained and stuttering promenades along Széchenyi út could be counted on to punctuate the monotony of village life, were nowhere to be seen, and—to the utter incredulity of all the village’s 278 permanent residents—even Feri and his perpetually filled pitcher of Kaiser sör had disappeared from the bench in front of the Italbolt.

As for Kormány Lajos, whom everyone credited with being the body whose hand had catapulted the stone through Pinlinszky’s window, neither he nor Gyula and Roland were anywhere to be seen. Rumors began to circulate that the foursome had stolen a car from the junkyard in nearby Szigliget and taken off for Transylvania. Nonetheless, fears that one or more of them, stones, blades or shotguns in hand, could resurface at any moment were more than enough to cast a melancholic pall over the village’s usual summer rituals of pig roasts, bonfires, wine tastings and infidelities.

Several nights after the shattering of Fischer’s window, Kepes, Fischer, the Mayor, and—at Etus’s urging—Árpi were meeting at the now-deserted Italbolt to discuss what action might be taken to restore peace and tranquility to the Hegymagasian summer.

“We must,” inveighed Kepes, “despite what has happened to our poor neighbor Fischer’s window, and to Árpi’s pig, allow an atmosphere of generosity and forgiveness to prevail.”

“Yes,” seconded the Mayor. “We are a small and peaceful village. We must love one another or die.”

Fischer, still contemplating the replacement cost of his destroyed window and his unsalvageable oleander, remained silent for a rare moment, as if contemplating not merely his own destiny, but the world’s future.

Árpi lifted a glass of plum pálinka skyward in a rather elegant arc, coming to a halt at his lips. “Yes,” he agreed, making a slurping noise with his tongue and casting a lascivious eye toward Kati the bartender, “we should all kiss and make up . . . for my mother’s sake if no one else’s. And who knows?—Kadar’s tail may yet grow back.”

“Well,” Fischer broke his silence with the reluctance of someone at an auction contemplating whether to bid far more than he had intended, “I’m not so sure. Peace and forgiveness have their place in the world, but so does justice. First it’s poor Fekete, then my clerestory window, and now Kadar’s tail. I, personally, have had more than my fill of those four bums and their troublemaking. Who knows what it will be next?

“It’s about time,” he continued, no doubt thinking about his own offspring, “that we set a better example for our children, and I see no reason why we shouldn’t begin right here and now.”

“It’s not exactly as if the two of you have been standing passively by watching the whole thing from the sidelines,” the Mayor reminded Fischer, taking on a rather scolding tone. “I think that Kormány’s sheep, Gyula’s parrot, Feri’s gumicsizma and Roland’s arm are a more than adequate display of village justice, don’t you?”

“I’m not sure.” Fischer seemed to be trying hard, at this point, to restrain a faint smile from trickling onto his lips. “I’m not at all sure.”

***

Yet another week went by, with still no sign of the fabulous foursome, or, for that matter, of the village’s usual spirit of lightheartedness and conviviality. Sipos Lajos, a carpenter from nearby Káptalantóti, was hard at work repairing Fischer’s window, and Árpi and Kadar—the latter with a splint and massive bandage appended to its disfigured tail—kept a hesitant vigil up in the vineyard.

A resonant emptiness—punctuated, periodically, by a visit by Kepes and Fischer for a glass of Slivovitz—echoed from the Italbolt, and even the village’s two garrulous Germans, Kronzucker and his wife Ulrike, seemed to have decided to curtail their weekly invitations for Bratwurst und Hefeweise at their backyard barbecue.

On this particularly torrid night, with a severe summer thunderstorm threatening, Horvath, Kepes, and Fischer were once again seated in the bar, a funereal pall having been cast over the former’s attempts at peacemaking by the latter’s intransigence and the other’s relative apathy.

“I guess it’s going to be a long, unfriendly summer,” Kepes remarked, lighting one of his socialist-era Kossuth cigarettes. “A very long summer.”

Suddenly, the front door of the Italbolt flew open, and in stumbled Feri, bootless and forlorn-seeming, his mud-strewn Yankee cap tilted to one side à la DiMaggio, a guitar with two broken strings grasped rather tentatively in his left hand. He was obviously drunk—more drunk, even, than usual—and, placing the guitar on one knee as he leaned backward against the ice cream freezer, began singing a bizarrely Hungarianized take on an old Peter, Paul, and Mary tune, now titled “Hova lett a sok halászlé?”—“Where has all the fish soup gone?”

“What a crazy sonuvabitch,” Fischer muttered under his breath, lifting his beaker of Slivovitz to his lips.

“I think it’s rather touching, in its own way,” Kepes observed. “The poor boy is merely a creative spirit gone astray.”

There was, however, on this particular occasion, a bit more to Feri’s melancholic tune than mere drunken creativity. “Why don’t you take a look outside, my friends,” he interrupted his tune to suggest. Followed closely by Kepes, Fischer made his way to the Italbolt door, from where—gathered across the street on the Post Office lawn beneath a blackening sky—he observed an incredible sight: NO MORE COOKING UNTIL WE HAVE PEACE! The two men read out loud from the large cardboard placard being held up on the post office lawn by none other than Etus néni, Terika néni, Vera néni, Rosza néni, Zsuza néni, Anikó néni and Kati néni—in other words, by all seven of the village’s surviving widows! The town’s women, led by Vera néni, had apparently decided that—Hungarian morality traveling, as it did, through the lower regions of the body—they would try and put an end to the summer’s hatreds and retributions by organizing a kind of culinary work stoppage.

“I don’t believe it,” Fischer turned incredulously to Kepes, who was unable to keep a hardly faint smile from trickling onto his lips. “Those crazy broads are actually organizing a strike!”

***

A strike, indeed, it turned out to be, as, over the next several days, the village’s usually abundant supply of fish soup, túrós rétes, paprikás csirke, mákos gombos, pörkolt, gulyás, and Hortobágyi palacsinta virtually dried up. The men of the village found themselves increasingly dependent on the fare offered by the grease-laden and radically overpriced Szent György Pince, or the more reasonably priced, but quantitatively miniscule, offerings at Jóska Bácsi’s new roadside restaurant, which simultaneously ran jeep tours of the vineyard, guided by the chef. Worse yet, many of them reverted to the sort of all-liquid diet that had already taken its toll on far too many Hungarians, both famous and infamous, in the past.

By the third day of the strike, Fischer was suffering from stomach cramps and diarrhea, Kepes’s ulcer had been aggravated by an excess of alcohol, and even the Mayor, whose damaged pancreas dictated a diet at some remove from the Hungarian norm (which his wife, before going on strike, had lovingly supplied) began suffering from severe nausea and insomnia.

Feri himself, somehow inspired to new levels of eloquence and sobriety by the strike, began, oddly enough, serving as a kind of middleman between the village’s peace-loving and newly undomesticated women and its disputatious men. “All they are saying,” he informed Horvath and Fischer later that week at the Italbolt, borrowing a line from one of his heroes, “is give peace a chance.”

Fischer, looking rather anemically pale, was cast into a state of profound reflection by Feri’s borrowed words. “Well,” he said, somehow forcing a conciliatory expression onto his features, “perhaps they have a point . . . This is getting to be a rather unpleasant summer, after all.” With the exception of the Italbolt’s proprietress, Kati, for whose business the conflict had proved an unexpected boon, all the other patrons, overhearing the conversation from their usual positions hunched over a pálinka, broke into applause. “Kössünk békét!” cried out Tibor the dairy farmer, “Let’s make peace!”

The Mayor, lifting his Slivovitz into the air, beamed with the air of a politician who had just brokered an agreement in the Middle East. “Then it’s decided,” he said. “We’ll have peace.” Fischer, following almost enthusiastically in his example, lifted his glass into the air. “Egészségedre . . . to Hegymagas!”

The next morning, a Saturday, an even stranger gathering than the previous day’s found itself amassed on the Post Office lawn. Feri, freshly shaven and showered and wearing his gray suit beneath his New York Yankees baseball cap, was seated on a high stool, guitar in lap. To either side of him, were standing Árpi and Etus, the latter in a freshly washed and ironed apron. Behind them were gathered some two dozen of the village’s children and, at the very rear—wearing somewhat alcohol-induced, but nonetheless genuinely amiable smiles—were Gyula, Roland, and, dressed in his Sunday best, Kormány.

At the sight of Fischer, Kepes, and the Mayor walking toward them down Széchenyi út, the gathered group, led by Feri’s rather arrhythmic strumming on the guitar, burst into song.

“All we are saaaaying,” the Hegymagasians sang in an English that would surely have made John Lennon wince in his grave, “is give peace a chance.”

“All we are saaaaying,” Etus, perpetually a good half-beat behind, intoned along, just as the sky opened and a torrential but soothing rain began to fall, “is give peace a chance.”

***

Hardly forty-eight hours later, Gyula’s mother awoke to the sound of a bird squawking “jó reggelt kivánok”—“Good morning”—loudly in Hungarian. She went outside to find a brand new parrot, in a filigreed wooden cage, mounted on a stand in front of her bedroom window. At virtually the same instant, just a few houses down Petöfi út, Feri, confined to his bed with a bad cold and a case of Kaiser sör, awoke in an inebriated haze to find a new pair of gumicsizma—made by the very best company in Györ—beside his front door.

Further up in the vineyard that morning, Roland entered his parents’ winemaking house on Szent Györgyhegy to find, to his amazement and delight—nestled right between the wooden casks that held his family’s precious Olaszrizling and Balaton Chardonnay—his missing wooden hand. And Kormány Lajos, when he went out to feed the horses that day, was greeted by the ravenous baahhhing of two young black baby sheep.

That night, all was well in the small village of Hegymagas once more. Fischer and the Mayor, in a rare spirit of mutual affection and camaraderie, lifted a glass in Etus’s honor at the Italbolt, joined by Roland, cradling his glass in his prosthetic arm. Feri, meanwhile—cold, hangover and all—was walking up and down Széchenyi út, proudly displaying his new rubber boots and humming a Hungarian version of “Love Me Tender.”

Even Kormány Lajos, in a rare spirit of conviviality and peace, could be found at yet another table in front of the pub, playing chess with—of all people—Árpi. But best—and, many people felt, most potent—of all in restoring the village’s usual atmosphere of tranquility and mutual affection was the scent of Etus’s fish soup, simmering in a gigantic kettle in front of the post office, wafting its way all the way up to Árpi’s vineyard and the appreciative nostrils of the new dog, Attila József, that Kormány had bought for her. The soup smelled—Kormány Lajos himself would later admit—as good, perhaps, as his own mother’s had once, and its aroma, he also acknowledged, was far more likely to prevail.