Читать книгу Forgotten Trials of the Holocaust - Michael J. Bazyler - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

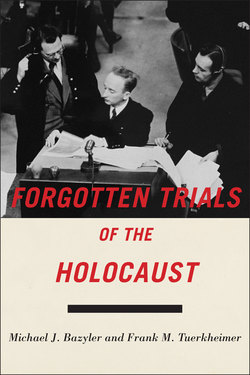

ОглавлениеThe four defendants at the Kharkov Trial: (l to r) Wilhelm Langheld, Reinhard Retzlaff, Hanz Ritz, and Mikhail Bulanov. Photo Archive, Yad Vashem.

1

The Kharkov Trial of 1943

The First Trial of the Holocaust?

In the brutal history of humanity, no other tragedy compares to the scale of death and destruction brought by Germany in the years between 1941 and 1945 to the territories of present-day Russia, Belarus and the Ukraine. During the forty-seven months of what is known in the region as the Great Patriotic War, approximately 30 million Soviet civilians and soldiers lost their lives. Twenty million of these were civilians. Over sixty years later, more than 2.4 million are still officially considered missing in action, while 6 million of the 9.5 million buried in mass graves remain unidentified.

When describing what befell them, the people of the region often reference the brutal hordes of Mongol invaders in Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Such an analogy is a fair one. In a throwback to the Mongol style of warfare, and on direct orders from Hitler, the German military on its Eastern Front did not follow the rules of warfare that had been developed by Europeans over the centuries to minimize civilian casualties as well as special status recognition of captured enemy soldiers.

Prior to the start of military operations in June 1941, Hitler announced to his generals: “The war against Russia will be such that it cannot be conducted in a knightly fashion. This struggle is one of ideologies and racial differences and will have to be conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful and unrelenting harshness.”1 Pursuant to Hitler’s instructions, the German generals issued specific orders to their regiments regarding how the upcoming invasion of the Soviet Union was to be conducted. This included the so-called “commissar order,” instructing the troops to take severe and decisive measures against “Bolshevik agitators” (the Soviet political commissars), partisans, saboteurs, and Jews. These orders provided the purported legal basis under German law for the mass executions of suspected political opponents and, eventually, Soviet Jews. It also permitted the German military to conduct a policy whereby approximately three million Soviet soldiers would die of starvation or cold in German POW camps.

In Ukraine, some of the fiercest battles between the German forces and the Red Army took place around Kharkov, Ukraine’s second-largest city. As a result of these battles, Kharkov became the only Soviet territory that changed hands four times during the war. The Germans captured Kharkov and the rest of eastern Ukraine in October 1941. In May 1942, the Red Army led a disastrous counterattack in an attempt to recapture the city. Hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers lost their lives in what David Glantz calls “one of the most catastrophic offensives in Russian military history.”2 In February 1943, the Red Army launched another offensive, this time successfully liberating the city. Soon thereafter, German forces countered with another attack, recapturing Kharkov in March 1943. This turned out to be the last major German victory on the Eastern Front. On August 23, 1943, the Red Army carried out what is known as Operation Rumiantsev and liberated Kharkov once and for all from German occupation.

Four months later, in December 1943, the Soviet Union conducted a trial in Kharkov of three captured Germans and one Ukrainian collaborator, charging them with the murder of Kharkov civilians, almost all Jews. The highly publicized Kharkov trial was the first trial of Germans held by any of the Allied powers. Earlier that year the Soviets held a public trial at Krasnodar, but the defendants were all Soviet citizens tried for treason stemming from their collaboration with the German invaders. The Soviets had also been conducting summary military trials of captured Germans, followed by quick executions. These, however, were not public trials and so were virtually unknown to the outside world. In contrast, the Kharkov trial was a highly publicized affair, and an attempt (partly successful, as we shall see) by the Soviets to conduct a Western-style legal proceeding.

It would take another two years, after Germany’s unconditional surrender in May 1945, for the Allies to organize and begin the trial of the so-called major war criminals at Nuremberg. As we noted earlier, the trial before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg was not, in a strict sense, a trial of the Holocaust since the murder of the Jews was not the central focus at Nuremberg. In Kharkov, in contrast, much of the focus of the trial was on the murder of the Jewish population of Kharkov, although not identified as such. Instead, the victims were referred to in the generic as “Soviet citizens”—for reasons discussed below.

The Holocaust in Kharkov

The Jews of the Soviet Union were the first group to be targeted for mass murder. Following the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, special action murder squads known as the Einsatzgruppen followed the regular German army into newly conquered territory. Operating just behind the advancing German troops, these mobile killing squads would round up and murder all the Jews and other “undesirables” such as the Roma and the Sinti (commonly known as Gypsies), perceived communist political leaders, professionals, and “criminals,” often with assistance from the local populace. The regular German armed forces, the Wehrmacht, also were heavily involved in the killings.

Later on, police battalions—initially organized to keep order in the occupied territories—joined in the killing process. They were supplemented by troops of the Waffen-SS (the military wing of the SS), the German Order Police, and non-German-staffed auxiliary police units comprised of Ukrainians, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Crimean Tartars, Belorussians, and Russians—all of whom participated in mass killings of civilians. As Israeli historian Yitzhak Arad notes: “A substantial number of people, particularly in the Baltic countries and Ukraine, collaborated with Hitler’s troops, and many participated in the murder of the Jews. Without the active support of the local inhabitants, tens of thousands of whom served in police units, the Germans would not have been able to identify and exterminate as many Jews in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union.”3

The murder operations in Ukraine were conducted by Einsatzgruppe C, organized with the other three Einsatzgruppen in a police academy in Pretzsch, a town about fifty miles southwest of Berlin. Einsatzgruppe C troops were transported to Ukraine, where they joined the Army Group South, composed of Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS troops, which spread itself across the western Ukraine, including Kiev and Kharkov. On September 19, 1941, German forces captured Kiev, the capital of Ukraine. Ten days later, detachment 4a of Einsatzgruppe C led by SS-Standartenführer (colonel) Paul Blobel massacred, over a period of two days, 33,771 Kiev Jews in the ravine at Babi Yar.

The German forces first entered Kharkov a month later, on October 23–24, 1941. In November 1941, they ordered that a census of the city be taken, in order to identify Jews among the population. In December 1941, the Jews of Kharkov were forced into a ghetto and then taken, in a similar fashion to Kiev, to the countryside to be shot. During this killing operation, at a ravine outside Kharkov known as Drobitsky Yar, approximately 15,000 Jews were murdered by the same detachment 4a troops and their collaborators. In total, Unit 4a—according to field reports sent to Berlin—executed 59,018 Jews in the Ukraine. The Drobitsky Yar mass grave is exceeded numerically only by the mass grave at Babi Yar, but remains largely unknown today to the outside world.

The Unknown Black Book, a compilation of testimonies from Jews who survived open-air massacres and other atrocities carried out by the Germans and their collaborators in Soviet territories, contains the testimony of one survivor of the Drobitsky Yar massacre, engineer S. S. Krivoruchko:

I, a resident of Kharkov, by nationality a Jew, by training an engineer, could not be evacuated from the city in October 1941, due to illness…. On the morning of December 14, a decree was posted throughout the city from the German commandant of Kharkov ordering all Jews to move to barracks on the grounds of a tractor factory within two days; persons found in the city after December 16 would be shot on the spot.

Starting on the morning of December 15, whole columns of Jews headed out of the city…. For many of the elderly and the handicapped, the journey from the city to the barracks of the tractor factory was the last of their lives. The corpses of no fewer than thirty old people lay on the ground. The pogrom began at about twelve o’clock, along with the robbing of the Jews who were on the move. As a result, many Jews arrived at the barracks without anything to their name and, more importantly, with barely any food….

The barracks … were one-story, ramshackle structures, with smashed windows, torn away floors, and holes in the rooftops…. In the room which I had found myself more than seventy people had arrived by evening, whereas no more than six to eight people would have been able to live in it under normal circumstances. People stood compressed against each other…. From the dreadful overcrowding, hunger and lack of water, an epidemic of gastro-intestinal diseases broke out…. Robbery and murder were daily occurrences. Usually, the Germans would burst into the room on the pretext of searching for weapons and would steal anything that came to mind. In the event of any resistance, they dragged people out into the yard and shot them….

On January 2, 1942, at 7:00 am … [a] German sentry shouted out an order for everyone to gather their things and be outside in ten minutes…. I went outside … then German sentries and policemen formed a tight ring around us and announced that we were being evacuated to Poltava. We marched out onto the Chuguyev-Kharkov highway but then were directed away from the city, although the road to Poltava ran through town. It was obvious that they were not taking us to Poltava. But where exactly we were going, nobody knew…. Two kilometers past the last houses of the tractor factory workers’ quarters, they turned us in the direction of a ravine. The ravine was strewn with bits of rags and the remains of torn clothing. It became clear why they had brought us here. The ravine was sealed off by a double row of sentries. On the edge of the ravine stood a truck with machine guns. Terrible scenes erupted when people understood that they had been brought here to be slaughtered…. Many said goodbye to each other, embracing, kissing, exchanging the last supplies they had….

From the standing column, the Germans began using clubs to drive groups of fifty to seventy people one hundred paces or so forward, then forcing them to strip down to their underwear. It was -20 or -25 degrees C. Those undressed were driven down to the bottom of the ravine from which were heard occasional shots and the chattering of machine guns.

I was in a daze and did not notice the screaming behind me. The Germans began driving forward the group that I was part of. I moved off, ready to die within a few minutes. Just then, something happened: the Germans brought up the aged and handicapped to be executed. The belongings of those who had been killed had been loaded onto these trucks and brought back to the city. I moved along behind one of these vehicles. Two young Jews were in the truck; the Germans had assigned them to do the loading. In a flash, I jumped into the truck and asked the youngsters to cover me. Then they hid themselves as well. When the truck was full, the German drivers took off with it and in this way took me and the two boys away from the awful ravine….

I went to find my wife (she is not a Jew and had stayed behind in the city with our adopted daughter) who hid me with a girlfriend of hers. I stayed with her for six and a half months. For four months later after that I wandered from village to village with a false passport and, in this way, held on until February 16, 1943, when Kharkov was liberated for the first time from the German occupiers.4

The German account of the roundup—Operational Situation Report U.S.S.R. No. 164, transmitted from the field to Berlin and dated February 4, 1942—summarizes the actions taken regarding the Jews of Kharkov:5

Einsatzgruppe C—Arrest of the Jews in Kharkov

The extensive preparations that became necessary in the matter of the arrest of the Kharkov Jews were sped up within the framework of SK 4a responsibilities. First of all, it was necessary to find a suitable area for the evacuation of the Jews. This was accomplished with the closest understanding of the municipality’s housing department. An area was chosen where the Jews could be housed in the barracks of a factory district [in Rogan on the edge of town]…. The evacuation of the Jews went on without a hitch except for some robberies during the march of the Jews in the direction of their new quarters. Almost without exception, only Ukrainians participated in the robberies. So far, no report is available on the number of Jews that were arrested during the evacuation. At the same time, preparation for the shooting of the Jews is underway. 305 Jews who have spread rumors against the German Army were shot immediately.6

An alternative method of killing used in the Kharkov region was through the use of carbon monoxide gas pumped though the exhaust of mobile death vans. The Nazis first tested carbon monoxide gas on Soviet prisoners of war in September 1941 at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, located north of Berlin. By the following year, approximately fifteen gas vans had fanned out throughout German-occupied Soviet territory to exterminate Jews and other “undesirables.” The victims were packed into the back of closed vans, specially sealed, while carbon monoxide was piped through a hose attached to the van’s tailpipe. The bodies were then unloaded, and either buried in mass graves or incinerated in open flames.

When the Red Army liberated Kharkov for the last time in August 1943, almost no Jews remained. That the Nazis had managed to make Ukraine (including Kharkov) judenrein is confirmed by the account of great Soviet Jewish writer and journalist Vassily Grossman, reporting from the field: “There are no Jews in Ukraine. Nowhere—Poltava, Kharkov, Kremenchug, Borispol, Yagotin…. All is silence. Everything is still. A whole people have been brutally murdered.”7

Grossman’s description is applicable for the rest of Soviet territory occupied by the Germans. Of the approximately 2.5 million Jews who had been trapped in German-occupied Soviet Union, only 100,000 to 120,000 survived. Most did so by joining the Jewish partisans or going into hiding. Yitzhak Arad sums up the aftermath: “All told, of the five million Jews who lived in the Soviet Union on the eve of the German attack on June 22, 1941, about half lost their lives as a result.”8

The Trial

As the Red Army liberated Soviet territory, it repeatedly found mass graves containing remains of Jews who had been systematically slaughtered. In the Kharkov region some of these sites were discovered after the first liberation in February 1943, but before the German troops recaptured the region a month later. Most of the Jews of Kharkov had already been murdered by that time. The Red Army liberated Kharkov for the second and last time in August 1943. The defendants on trial were part of the German troops captured during this last liberation.

Earlier in the year, in July 1943, the Soviets put eleven local Soviet citizens who collaborated with the Nazis on trial in the northern Caucasus city of Krasnodar. After a three-day trial, the eleven Krasnodar defendants were found guilty of treason. Eight were executed and three were given sentences of twenty years of hard labor.

On November 1, 1943, the foreign ministers of the U.S., U.K., and U.S.S.R. issued the so-called Moscow Declaration, putting on notice Germans participating in “atrocities, massacres and executions” that they would be tried for their “abominable deeds” in the countries where they committed these deeds. The Kharkov trial of December 1943, the first public trial of German nationals by any Allied power, was the Soviet signal to the Allies that they were now putting into practice the Moscow Declaration. Greg Dawson, in his Judgment before Nuremberg, rightly labels the Kharkov trial as “the first Nazi war crimes trial.”9

Three Germans and one Ukrainian were tried in Kharkov before a military tribunal constituted by the 4th Ukrainian Front of the Red Army, composed of three military judges. The prosecution of the case was led by a military colonel with a legal background, State Prosecutor of Justice Colonel N. K. Dunaev. Three Soviet defense counsel were appointed to represent the defendants. A six-member forensic team of medico-legal experts also took part in the trial, serving as expert witnesses and providing a report.

The four-day trial began on December 15, 1943, exactly two years after the German massacre of the Kharkov Jews at Drobitsky Yar. To accommodate the large attendance, and to provide the necessary gravitas to the proceedings, the trial was held in the auditorium of the Kharkov Dramatic Theater. The theatrical atmosphere was accentuated by the illumination of the auditorium with klieg lights, used to film the proceedings by a slew of cameras. The audience was rotated each day to ensure maximum attendance. Foreign correspondents were specifically invited to attend but, due to a glitch, only arrived on the last day of the trial.

The most knowledgeable of the foreign observers was American journalist Edmund Stevens. Stevens was a seasoned Soviet “old hand” who first went to the Soviet Union in 1934 to study the “Russian experiment” and married a Russian woman who returned with him and their son to the United States before the war. In 1945, he published Russia Is No Riddle,10 describing his journeys through the Soviet Union before and during the Second World War. The book included a chapter about his visit to the Kharkov trial. Unlike some Westerners that became enamored with the Bolshevik revolution, and so viewed all things Soviet in a positive light, Stevens aimed to be objective about what he observed. His descriptions of the court proceedings in the Kharkov Dramatic Theater reflected this critical outlook:

The Russians are past masters at mise en scène,11 and the atmosphere of that Kharkov trial room was distinctly reminiscent of the famous Treason Trials of 1936–38. In fact, two of the defense lawyers, Kommodov and Kaznacheyev, had defended some of the figures in the treason trials. Their presence provided an element of direct continuity. This, too, was a military tribunal: judges, prosecutor, and attendants were all in uniform….

During the recesses, I discovered that many of the people in the audience had personal knowledge or experience of the events and atrocities described, and had seen or known the defendants during the German occupation. Several times during more gruesome bits of evidence there were stifled sobs from some woman—not out of pity for the defendants. For the most part the proceedings took place against a background of concentrated silence.12

The defendants were correctly characterized by Stevens as “small fry” and “non-entities”13—chosen to embody various ranks of the German military command that occupied the Kharkov region. He describes the three Germans on trial at Kharkov as follows:

• Wilhelm Langheld, a fifty-two-year-old captain of the German Military Counter-Espionage Service (Abwehr) and a commander of a POW camp for Soviet prisoners. Stevens describes Langheld as “stocky, red-headed [and] beefy-faced … whose carriage, heel-clicking, and rows of ribbons proclaimed a German soldier of the old school.”14

• Hans Ritz, an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) in the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), one of the security organizations of the SS, and an assistant SS Company Commander of a Sonderkommando unit. Stevens describes Ritz as a “Nazi horse of a different color from the hard-bitten Langheld[,]…. a baby-faced youth of twenty-four, with a tender little mustache.”15 Ritz, trained in music and law, worked as a lawyer before fighting with the SS on the Eastern Front.

• Reinhard Retzlaff, a thirty-six-year-old corporal and member of the 560th Group of German Secret Field Police. Unlike the other two German defendants, Retzlaff was not a Nazi Party member.

All three Germans were charged with playing a “direct part in [the] mass and brutal extermination of civilian Soviet people by the use of specially equipped automobiles known as ‘murder vans,’ and also with having taken a personal part in mass shootings, hangings, burnings, plunder and outrages on Soviet people.”16

Along with the three Germans on trial, the Soviets added a Soviet citizen: Mikhail Bulanov, a twenty-six-year-old Ukrainian collaborator who worked with the Germans from October 1941 to February 1943. The indictment characterized Bulanov as a shafior (chauffeur) with the Kharkov Sicherheitsdienst. Bulanov was charged with “betrayal of the motherland … [and] with having taken a direct part in the mass extermination of the Soviet people by means of asphyxiation in ‘murder vans,’ [and] with having personally shot civilian Soviet citizens, among whom were old people, women and children.”

The four defendants were charged under both international law and Soviet law. The legal basis under international law was the Moscow Declaration issued by the Allies a month earlier announcing that Germans participating in atrocities would be tried by the countries where the atrocities took place. In the sphere of the Soviet legislation, on April 19, 1943, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (parliament) of the U.S.S.R. issued a decree entitled On measures of punishment for German-Fascist villains guilty of killing and torturing the Soviet population and captive Red Army soldiers, for spies and traitors to the Motherland from among Soviet citizens and their accomplices.17 The April decree became the prime legal tool for prosecution of German Nazis and their Soviet collaborators. Alexander Prusin notes that “[t]he [April] decree became a binding tool with which to handle all accused war criminals, and its very language signifies its designation as an instrument of deterrence against collaboration with the Germans.”18 The decree used the terms “atrocities” and “evil deeds” to broadly encompass the war crimes committed by the German (foreign) and Soviet (domestic) war criminals while stipulating punishment by public execution or long-term prison time.19

The German defendants appeared in court dressed in full military attire, which was not common in Soviet trials. After public reading of the indictment,20 the defendants all entered guilty pleas. However, under continental civil law legal systems, emulated by Soviet socialist law, a plea of guilty is not automatically accepted by the court. The court must still satisfy itself that the evidence proves the guilt. Additionally, evidence is presented to help determine what sentence should be rendered. The trial, therefore, continued despite guilty pleas.

Undoubtedly, the Soviets did not constitute this public trial for the defendants merely to plead guilty and subsequently sentence them without going into specifics of the atrocities committed. Almost all public trials held of Nazi war criminals and collaborators over the last seventy years have had a didactic component, and this first trial of the Nazis was no exception. Detailed evidence of the brutal atrocities committed by the “Fascist-Hitlerite” invaders in the Kharkov region was going to be introduced during the trial and subsequently disseminated to the outside world. As confirmation of this intent, the Soviets translated excerpts of the proceedings into English shortly after the trial’s conclusion and published them in a book, The People’s Verdict. The book included commentary and also excerpts from the Krasnodar trial. The Soviets also produced a documentary, which was widely shown in Soviet theaters, though never screened in the West.

Stevens, the American correspondent, noted that “all legal niceties were observed to a fault. The defendants and their counsel had full latitude to speak or interpolate, and every comma of what was said was translated into German for their benefit.”21 Each defendant took the stand and was questioned by the prosecutor, members of the tribunal, and defense counsel. George Ginsburgs comments that “[t]here [was] no indication that the German defendants had either been rehearsed or coerced.”22

The trial began with the most senior of the three German defendants to take the stand: Captain Wilhelm Langheld. He explained that the German high command encouraged atrocities against civilians and decorated soldiers for fulfilling orders to exterminate Soviet citizens.23 Langheld described the use of gas vans by the German military for mass slaughter:

I saw the “gas van” in Kharkov … [s]ome time in May, 1942, when I was on a service visit to Kharkov…. As far as I remember the “gas van” is a vehicle dark grey in colour, completely covered in, having hermetically sealed doors at the back…. [It holds] [a]pproximately 60 to 70 persons…. I was at 76, Cherniskevsky Street at the H.Q. of the S.D. and heard a terrific noise and screaming outside…. A gas van at that moment had driven up to the main entrance of the building, and one could see how many people were being forcibly driven into it, while German soldiers were standing at the doors of the van…. I was a few paces away from the gas van and saw it being done…. Among the people being loaded into the gas van were old men, children, old and young women. These people would not go into the machine of their own accord and had therefore to be driven into the gas van by SS men with kicks and blows of the butt ends of automatic rifles…. I presume that these people guessed the sort of fate that awaited them.24

Describing the child of a woman who was killed, Langheld explained: “He clung to his dead mother, crying aloud. The lance-corporal who came to take away the woman’s body got tired of this so he shot the child…. Such things happened everywhere. It was a system.”25

Stevens described his observation of Langheld’s testimony:

When the prosecutor asked Langheld whether the German High Command ever punished its soldiers or officers for ill treatment of civilians, he pondered a moment, rocking slightly back and forth on his toes and heels, and then answered, in the same quiet, measured voice in which his entire testimony had been delivered, that on the contrary such treatment was deliberately encouraged and rewarded. At each conclusion of his testimony, Langheld saluted smartly, turned on his heels, and strode back to his seat in the prisoners’ box. 26

The next defendant to take the stand was Second Lieutenant Hans Ritz, who testified that the functions fulfilled by SS troops included “shooting, forcible evacuations of villages, [as well as] the transportation and guarding of arrested persons.”27 Like Langheld, Ritz also indicated his awareness of “the extermination of civilian citizens in Kharkov”28 and his involvement in such killings. Prosecutor Dunayev sought out Ritz’s mindset for his murderous acts:

PROSECUTOR: You, Ritz, are a person of higher legal education and apparently consider yourself a man of culture. How could you not only watch people being beaten, but even take an active part in it, and shoot perfectly innocent people, not only under compulsion but of your own free will?

RITZ: I had to obey orders, otherwise I would have been court-martialed and certainly sentenced to death.

PROSECUTOR: This is not quite so, because you yourself expressed a desire to be present when people were loaded on to the gas vans and nobody specially invited you to be there.

RITZ: Yes, that is true. I myself expressed a desire to be present, but I beg you to take into consideration that I was then still a newcomer on the Eastern Front and wanted to convince myself as to whether it was true that these lorries of which I had heard were used on the Eastern Front. Therefore, I expressed my desire to be present when people were loaded on them.

PROSECUTOR: But you took a direct part in the shooting of innocent Soviet citizens?

RITZ: As I have testified earlier, during the shooting at Podvorki, Major Hanebitter said to me: “Show us what you are made of,” and, not wanting to get into trouble, I took an automatic rifle from one of the SS men and started firing.

PROSECUTOR: Consequently, of your own free will you entered upon this vile course of shooting completely innocent people, as nobody had forced you to do it.

RITZ: Yes, I must admit that.

Ritz also acknowledged that German policy was not to recognize the laws of warfare on the Eastern Front:

PROSECUTOR: Now, Ritz, you are a man with some knowledge of law. Tell us, were the standards of international law observed to any extent by the German Army on the Eastern Front?

RITZ: I must say that on the Eastern Front there was no question of international or any other law.

PROSECUTOR: Tell us, Ritz, on whose orders did all this take place? Why was this system of complete lawlessness and monstrous slaughter of perfectly innocent people instituted?

RITZ: This lawlessness had its deep seated reasons. It was instituted on the instructions of Hitler and his collaborators, instructions which are capable of detailed analysis.29

The third defendant to take the stand was Corporal Reinhard Retzlaff. His testimony included a description of how he participated in the murder of Soviet civilians.30

PROSECUTOR: Tell the Court how you exterminated Soviet citizens.

RETZLAFF: Every person detained by the military authorities and sent to the Secret Field Police for examination, was first of all beaten up. If a prisoner gave the evidence we needed, the beatings were discontinued, while those who refused to give evidence were further beaten, and this frequently resulted in their death.

PROSECUTOR: This means that if a person did not confess, he was murdered. And if he did—he was shot. Is that correct?

RETZLAFF: Yes, that was so on most occasions.

PROSECUTOR: Was there any occasion when cases were trumped up and evidence was faked?

RETZLAFF: Yes, all this happened and rather frequently. One may say that this was quite normal procedure.

The final defendant to take the stand was Bulanov, who described the transport of medical patients from a hospital to shooting sites. Bulanov acknowledged that on four occasions he drove a three-ton truck with a total of about 150 patients from the Kharkov hospital to a shooting site:

BULANOV: When I arrived at the hospital I was told to drive up to one of the hospital blocks. At this moment Gestapo men began to lead out patients dressed only in their underwear, and load them into the trucks. After loading, I drove the truck to the shooting site under German escort. This place was approximately four kilometers from the city. When we arrived at the shooting site, screams and sobs of patients who were already being shot filled the air. The Germans shot them in front of the other patients. Some begged for mercy and fell down naked in the cold mud, but the Germans pushed them into the pits and then shot them.31

Bulanov also discussed a similar trip from a children’s hospital to transport children aged six through twelve for extermination.32

Once examination of the defendants was concluded, the court and counsel proceeded to interrogate percipient witnesses. These included both Kharkov residents (including hospital personnel) who witnessed the atrocities as well as captured German soldiers. None testified directly about the defendants on the dock. Rather, their testimony served as background, adding to the overall picture of the horror that had taken place in the Kharkov region: mass shootings, gas van descriptions, discussions of the plunder of agricultural products, instructions from superiors in command (to implicate those higher-ranked officials), the disgraceful prison camp conditions, and murder of hospital patients.33

As part of the prosecution case, forensic experts from the Commission of Medico-Legal Experts also testified and presented a report based upon their examination of the various mass graves found at the Drobitsky Yar gully and other places in the Kharkov region. The expert report confirmed by forensic evidence that the methods of murder by the German forces of local civilians and POWs consisted of shooting the victims and gassing them through the use of carbon monoxide.

The medico-legal experts examined in Kharkov and neighbouring localities the scenes of the crimes of the German fascist invaders—the places where they carried out the extermination of the Soviet citizens. These included the burned-out block of the army hospital, where they shot and burned war prisoners—severely wounded personnel of the Red Army; the place of the mass shooting of the healthy and sick, of small children, juveniles, young people, old men and women in the forest park of Sokolniki, near the village of Podvorki, in the Drobitsky gully, and in the therapeutic colony of Strelechye. At these sites the medico-legal experts examined the grave-pits and exhumed bodies of Soviet citizens shot, poisoned, burned or otherwise brutally exterminated.

The medico-legal experts examined the places where the German fascist invaders burnt bodies to destroy evidence of their crimes—the poisoning with carbon monoxide. This is the site of the conflagration on the territory of the barracks of the Kharkov tractor plant. Examination of territories on which bodies were burnt or buried, examination of the grave-pits and positions of bodies in them and comparison of material thus obtained with data of the Court proceedings, provide grounds for considering that the number of bodies of murdered Soviet citizens in Kharkov and its environs reaches several tens of thousands, whereas the figure of 33,000 exterminated Soviet citizens given by accused and some witnesses is only approximate and undoubtedly too low.

In the 13 grave-pits opened in Kharkov and its immediate vicinity were found a huge number of corpses. In most graves they lay in extreme disorder, fantastically intertwined, forming tangles of human bodies defying description. The corpses lay in such a manner that they can be said to have been dumped or heaped but not buried in common graves. In two pits in the Sokolniki forest park bodies were found lying in straight rows, face downward, arms bent at the elbow and hands pressed to faces or necks. All the bodies had bullet wounds through the heads. Such a position of the bodies was not accidental. It proves that the victims were forced to lie down face downward and were shot in that position…. The fact revealed by the investigation—namely, that before being murdered Soviet citizens were stripped of their footwear—is fully confirmed by the medico-legal examinations: during exhumation the experts in most cases discovered naked or half-naked bodies.

In order to ascertain which Soviet citizens were exterminated and in what manner, the experts exhumed and examined 1,047 bodies in Kharkov and its environs. These included the bodies of 19 children and adolescents, 429 women and 599 men. The dead ranged in age from two to seventy years. The fact that the bodies of children, adolescents, women and old men as well as invalids were discovered in grave-pits with civilian clothes and articles of domestic use and personal effects on the bodies or near them proves that the German fascist authorities exterminated Soviet citizens regardless of sex or age. On the other hand, the fact that [among] the bodies of young and middle-age men were found clothes of military cut worn in the Red Army, also articles of military equipment (pots, mugs, belts, etc.) is evidence of Soviet war prisoners. […] On the basis of all the combined data of their proceedings—the medico-legal experts have established the presence of: (a) A vast number of burial sites in the city of Kharkov and its immediate environs. (b) A huge number of bodies in the grave-pits. (c) Varying times of burial in various graves. (d) Varying degrees of preservation of the bodies in the same graves. (e) Distinction of bodies in regard to sex and age. (f) Uniformity of methods of extermination of human beings.

We regard the above as proofs of systematic, methodically organized, mass extermination of Soviet civilians and war prisoners.34

The defense strategy was to argue that ultimate guilt for the defendants’ crimes lay with the Nazi regime and immediate higher-ups. Langheld explained: “I fulfilled the orders of my superiors. Had I not done so I would have been court-martialed.”35 Retzlaff stated: “I plead guilty to all the crimes I have committed upon the orders of my immediate command.”36 The reliance on following superior orders and the defense of duress were, of course, the most-repeated defenses in subsequent trials of Germans and local accomplices by the Allies, both at Nuremberg and thereafter.

On the morning of December 18, 1943, after three days of testimony, prosecutor Dunayev gave his closing argument. While seeking to confirm that the defendants all acted on the superior orders of others, he argued that this should not exculpate defendants from their personal guilt. In so doing, Dunayev utilized an argument that was later to be used in the Nuremberg trials: German law itself rejected the defense of superior orders. The precedent specifically relied on by Dunayev was a result of the trials held in Weimar Germany after the First World War before the German Supreme National Tribunal at Leipzig, where German judges found German military defendants guilty of war crimes.37

One of the classic decisions from the Leipzig tribunal is the Llandovery Castle case in 1921, in which two German naval submarine officers were convicted of war crimes for shooting survivors in lifeboats after torpedoing the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle, despite the fact that their acts of shooting upon the lifeboats was carried out on orders of their submarine captain. Dunayev specifically referred to the case in his closing argument.38

Dunayev concluded on an emotional note. After an obligatory nod to “[t]he heroic Red Army, led by the great Stalin,” he ended:

Concluding my speech for the prosecution, I appeal to you, citizen judges, to inflict severe punishment on the three base representatives of fascist Berlin, and on their abominable accomplice, who are sitting in the dock, to punish them for their bloody crimes, for the sufferings and the blood, for the tears, for the lives of our children, of our wives and mothers, of our sisters and brothers!

Today they are answering to the Soviet Court, to our people, to the whole world, for the felonies they committed on a scale and of a baseness far surpassing the blackest pages of human history, the horrors of the Middle Ages and of barbarism! Tomorrow their superiors will have to answer—the chieftains of these bandits who invaded our peaceful, happy land on which our people toiled, reared their children, and built our free State. I accuse Retzlaff, Ritz, Langheld, and Bulanov of the crimes specified in Part I of the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R., dated 19th April 1943.

In the name of the law and of justice, in the name of tens of thousands of peoples maimed and tortured to death, in the name of the entire people—I, as State Prosecutor, beg you, citizen judges, to sentence all four base criminals to death by hanging.39

Defense counsel did not argue with the prosecution’s request for a guilty verdict, only that extenuating circumstances called for the defendants’ lives to be spared. Defense counsel Kommodov explained: “[T]hese men were made into assassins by, first of all, killing their souls, and it is this doubt which gives me, comrades, judges, the moral right to pose the question of the possibility of a lesser penalty than that demanded by the Prosecutor.”40 His colleague, defense counsel Kaznacheyev, described the crimes as being committed by an army in which “human feelings were considered a weakness, and ruthlessness and fanaticism a virtue.”41 Focusing on defendant Retzlaff, Kaznacheyev argued that because “Retzlaff … is now conscious of what he has done and has undergone a psychological transformation, I consider it possible to ask that his life be spared.”42 With regard to Bulanov, the defense argued that he also had repented, and this should be taken into account in the determination of a final sentence.43

The four defendants were allowed to make final statements. Langheld stated: “I do not want to minimize my guilt in any way, but I should like to point out that the underlying reasons for all the atrocities and crimes of the Germans in Russia are to be sought in the German Government…. The Hitlerite regime has succeeded in stifling the finest feelings of the German people, by implanting base instincts in them.”44 According to Langheld, who argued that he had to follow the evil “orders or directives” of his superiors, like the deceased, “I was also a victim of these orders and directives.”45 Retzlaff repeated the defense of compulsion: “If I had not obeyed these orders, I would have been put in the same position as my victims.”46 Bulanov begged: “I ask one thing of you, citizen judges, that in passing sentence you spare my life so that I may in the future atone for my guilt before the country.”47

Ritz, the young lawyer, gave the most eloquent speech in an attempt to save his life. Like Langheld, he argued the defense of duress: “I would like to ask the Court to take into consideration an old principle of Roman Law: Crime under duress. You must believe me that if I had not obeyed orders I should have been arraigned before a German military tribunal and sentenced to death.”48 But he then detailed particular circumstances that led him to commit his crimes:

I beg you, gentlemen of the Court, also to take into consideration the facts of my life. When the Hitlerite system came to power I was a child of only thirteen. From that time on I was subjected to the systematic and methodical influence of the Hitlerite system and education in the spirit of the legend of the superiority of the German race; an education which taught me that only the German people were destined to rule, and that other nations and races were inferior and should be exterminated. I was subjected to systematic training by such teachers as Hitler, [Alfred] Rosenberg, and Himmler, who educated the whole German people in the same spirit.

At the beginning of the war new propaganda came from these same sources, although these were encountered before the war. I have in mind the idea that the Russian people were uncultured and inferior. That is what they taught us. Then, with total mobilization I was sent to the front. When I reached the Eastern Front I was convinced that there was not a word of truth in these fables of Hitler, Rosenberg, and others; that on the Eastern Front the Germans did not have the slightest understanding of any tenets of international law; that there was no justice here in all the actions of the German authorities. But nothing remained to me but to continue along the same path. On the Eastern Front, I was also convinced of another thing, namely that a system on the banner which is inscribed the words “murder and atrocities” cannot be a right system.

I realize that the destruction of this system would be an act of justice. I am young. Life is still only beginning with me. I request you to spare my life so that I may devote myself to the struggle against that system.49

The tribunal judges returned with a verdict later that evening. All four defendants were found guilty. The tribunal described the individual guilt of each defendant as follows:

• Wilhelm Langheld … personally fabricated a number of cases in which about 100 perfectly innocent Soviet war prisoners and civilians were shot.

• Hans Ritz … directed the shootings carried out by the S.D. Sonderkommando in Taganrog, and during the examination of prisoners beat them up with ramrods and rubber truncheons, thus trying to extort from them false statements.

• Reinhard Retzlaff … tried to extort from them [Soviet civilians] false statements by means of torture—plucking out their hair and torturing them with needles, drew up fictitious reports in the case of 28 arrested Soviet citizens…. He personally drove into the “murder van” Soviet citizens doomed to death, accompanied the “murder van” to the place of unloading and took part in the burning of bodies of asphyxiated people.

• Mikhail Petrovich Bulanov, having betrayed the Socialist motherland, voluntarily sided with the enemy, joined the German service as a chauffeur with the Kharkov Gestapo branch, personally took part in the extermination of Soviet citizens by means of the “murder van,” drove peaceful Soviet citizens to the place of shooting and took part in the shooting of sixty children.50

All four defendants were sentenced to death by hanging, with no right to appeal. As Stevens observes: “The sentence of hanging was read by the chief judge around midnight, in a final blaze of klieg projectors.”51

The next morning, on December 19, 1943, at 11 a.m., the defendants were publicly hanged in Kharkov City Square. Stevens describes the hanging:

It was all over in a few moments. The defendants were hoisted into the back of four open trucks and stood on stools. Then the nooses were looped around their necks. There was no blindfolding. During the preliminaries three of the four prisoners had to be propped up. Bulanov had fainted; Ritz and Retsalu [Retzlaff] had turned pasty white; they drooled at the mouths and their knees gave way. Only Langheld, the old soldier, remained stiff as a ramrod throughout, never once flinching. Once the nooses had been adjusted, at a signal the trucks pulled away and the four were left dangling and kicking in mid air.52

In 1944, the Soviet Union released a full-length documentary of the trial, which was screened throughout the Soviet Union and also in London and New York. Seven months after the trial, Life magazine published a full two-page spread with photos (taken from the documentary film stills) and brief descriptions of the trial and its participants.

The Kharkov Trial’s Three Audiences and the Absence of Jews as Victims

The Soviets organized the Kharkov trial for three audiences: (1) their domestic audience, the Soviet populace fighting for their liberation from Germany; (2) their international audience, the U.S.S.R.’s British and American allies with whom they were in a common cause to defeat Nazi Germany; and (3) their enemy, the German military and German political leaders. In this sense, the Kharkov trial was a “show trial,” where political considerations led to the creation of the judicial proceedings. Stalin’s strategy towards these three audiences each featured different considerations, and the trial was supposed to satisfy all of these.

On the home front, Stalin used the media to publicize the trial and link it to the victories of the Red Army.53 Not only did the publicity aim to promote a positive image of the Soviet Union, but also a negative image of the enemy to “satisfy popular demand for revenge and to stimulate further hatred of the enemy.”54 The Soviet Union, in the view of American Ambassador Averell W. Harriman, “meant to show Soviet citizens that the government was sincere in its promise to punish the Germans and to lose no time in doing so.”55 The Soviet official daily Pravda declared: “The sword of the Red Army and the armies of our Allies are victoriously preceding the sword of justice…. The sword will not be sheathed until the leaders of the cursed Fascist band shall answer with their heads for their crimes against humanity.”56 In effect, Stalin wanted to keep Soviet spirits high in order to ensure success in the war effort.

On the international front, Stalin wanted to exhibit the Soviets’ determination to track down, and hold responsible, war criminals.57 Additionally, Stalin may have wanted to ensure that his allies, the British and Americans, would “keep their pledge about bringing ‘war criminals’ to trial.”58

Finally, Stalin sought to deter Germans from creating further harm while they were in retreat from Soviet territory. Harriman asserted that the Soviets sought to create a fear of retribution among the German army ranks and the SS as well as to encourage the Soviet resolve “to hold individual Germans responsible for crimes committed by them even though they were acting on direct orders from their superiors.”59 An article in the Washington Post posited at the time: “The Kharkov trial is a warning to th[e German nation], a warning not merely to Hitler and his hierarchy, not merely to Himmler and his menagerie of trained brutes, but also to the rank and file in the German army, to the German officer class, to Germans generally that as far as the Allies are concerned guilt will be personal as well as collective.”60

In reviewing the Kharkov trial proceedings, we observe one glaring omission: the word evrei (Jew) is never uttered during the trial nor does it appear in any court document. Rather, the primary murder victims of the German invaders are described in generic terms as “civilian Soviet people,” “Soviet citizens,” or “peaceful civilians.” The initial indictment termed the herding of the Jews of Kharkov into a ghetto as the “forceful resettlement of Soviet citizens”—hiding the fact that only Jews were forced to ghettoize while the rest of the local population were free, for the most part, to go about their daily lives, albeit under German occupation.

Even when different groups are mentioned, the Jews are specifically omitted. In his closing address, Prosecutor Dunayev refers to the extermination campaign fashioned by the Nazi leaders:

It is a matter of common knowledge that these [atrocities at Kharkov] are no accidental crimes of individual Germans, but a thoroughly considered, well-worked-out programme for the extermination of the Russian, Ukrainian, Byelorussian, and other peoples, that this was a system of annihilation of the population in the temporary occupied districts of the Soviet Union.61

In their verdict, the judges found Langheld guilty of “shooting and atrocities against … the civilian population.” Ritz was also found guilty of “shooting Soviet civilians.” Retzlaff and Bulanov “personally drove into the ‘murder van’ Soviet citizens doomed to death” and “personally took part in the extermination of Soviet citizens by means of the ‘murder van,’” respectively, without mentioning that it was Jews who were in those vans. The verdict also completely de-Judaizes the ghettoization of the Jews of Kharkov and the Drobitsky Yar massacre, referring to “Soviet civilians … [being] turned out of their houses in the town into barracks in the area of the Kharkov Tractor Factory. Later they were taken away in groups of two to three hundred to a gully in the vicinity and were shot.”62

In publicizing the Kharkov trial, noted Soviet war correspondent Ilya Ehrenburg tried to correct this glaring omission against his Jewish brethren by writing in his dispatches “explicitly about the Jewish victims and descri[bing] with contempt how German officers spoke without emotion about helpless [Jewish] women and children, as if hoping they could ‘emerge dry from the water.’”63 Robert Chandler explains the Soviet policy of avoiding the mentioning of Jews as specific targets of the Nazi murder process:

The official Soviet line … was that all nationalities had suffered equally under Hitler; the standard retort to those who emphasized the suffering of the Jews was “Do not divide the dead!” Admitting that Jews constituted the overwhelming majority of the dead would have [also] entailed that other Soviet nationalities—and especially Ukrainians—had been accomplices in the genocide; in any case, Stalin was anti-Semitic.64

The omission of Jews from the historiography of the Great Patriotic War continues, unfortunately, to the present day. In 2000, more than a half-century after the trial, the Drobitsky Yar Memorial Committee in Kharkov installed a plaque at the entrance of the Kharkov Theater to commemorate the trial. It reads, in Ukrainian:

In this building, on 15–18 December, 1943 there took place the first trial in history of war criminals for atrocities they committed against the civilian population of Kharkov and Kharkov region, who, according to verdict of the Military Tribunal of the 4th Ukrainian Front, were sentenced to death by hanging.

Was the Kharkov Trial Another Typical Stalinist Show Trial?

The show trial is one of the special hallmarks of the Stalin era and of Stalinism. The first Stalinist purge trial of fellow Communist Party members in August 1936 typifies the process by which Soviet courts became instruments of political repression. Sixteen party leaders were charged in organizing a “terrorist” center on behalf of the exiled Leon Trotsky. After their arrest and interrogation, most confessed to the false charges—a common occurrence in such trials. Stalin’s instructions to the secret police, the NKVD, for interrogation were as follows: “Mount your prisoner and do not dismount until they have confessed.”65 Defendants were told (falsely) that if they signed a confession, their lives would be spared. Prosecution witnesses were forced to provide false evidence by the same method.

For those trials, as William Chase notes, Stalin was the producer, controlling the show in the courtroom. For the August 1936 trial, Stalin “helped phrase the charges, decided on the slate of defendants, crafted the [false] evidence, and prescribed the sentences. He even dictated [prosecutor Andrei] Vishinsky’s emotional speech as the grand finale of the trial and polished its style.” 66

Considering the pedigree of the trial process in Stalin’s Soviet Union and when it took place, it is difficult to see the Kharkov trial as anything other than one more Stalinist show trial. The making of a full-length documentary film on the trial and its screenings in Soviet movie theaters adds to this notion. Even the publication in English in 1944 of the proceedings of the Kharkov trial, to be sold in the United States and the U.K., is further proof that the Kharkov trial followed in the tradition of a typical Stalinist show trial.

With regard to Soviet show trials, Susan Arnold notes that there is a gulf difference between Soviet-style show trials and a true war crimes trial: “A real trial involves risk and assuming that risk is a political decision.”67 Why were the Nuremberg trials not show trials? The consensus is that because not all of the defendants were convicted. As noted by David Luban: “The best proof of the fairness of the Nuremberg Tribunal lies in its acquittal of such major figures of the Third Reich as Fritzsche, Papen, and Schacht.”68

The “show” element of the trial, however, does not necessarily make the trial unfair. Rather, in addition to providing procedural due process, the trial can be used for a didactic purpose. The Eichmann trial was a show trial in that sense also, since Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and prosecutor Gideon Hausner aimed to use the trial of Eichmann to teach both young Israelis and the outside world about the Holocaust. As Lawrence Douglas observes: “The Eichmann trial, even more explicitly than Nuremberg, was staged to teach history and shape collective memory.”69

Modern-day proceedings before international criminal tribunals, such as the International Criminal Court and the U.N.-created tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, likewise have an important “show” element to them. As Asli Bâli has noted: “Trials that exemplify international standards of accountability for atrocities are for show in the best possible sense: they provide a public forum for local and international audiences that demonstrates that justice is being served and leaders are being held accountable for their crimes.”70 For this reason, Jeremy Peterson asserts: “[T]his does not mean that all show trials are damnable. It also may be true that some show trials are defensible.”71

The Kharkov trial can be characterized as such a defensible show trial. As Arieh Kochavi observes:

American correspondents who followed the trial [in Kharkov] and attended the hanging of the convicted men were generally convinced of the guilt of the accused and of genuineness of the Soviets’ charges of organized atrocities. They thought that the Russians had been punctilious in their observance of the legal proprieties of the trial and found no evidence of duress. The self-abasing testimony of the accused, the journalists observed, was reminiscent of the purge trials of the mid-1930s. Still, this was largely attributed to the care that had been exercised in selecting those who were placed on trial.72

Unlike a paradigmatic “show trial,” whose purpose is to stage-manage falsehoods, the defendants on the dock in Kharkov were indeed guilty of the crimes accused. From the perspective of Greg Dawson, whose mother and aunt are the last-known living survivors of the Drobitsky Yar massacre, the Kharkov trial, “[s]ymbolically at least, was the trial of the men who murdered my grandparents and great-grandparents at Drobitsky Yar…. If this was a ‘show trial,’ it was because the victims were showing the perpetrators far more justice than they deserved.”73 Soviet Jewish lawyer Aaron N. Trainin, in the aftermath of the trial, correctly observed that in the Kharkov trial defendants “were tried for the misdeeds which they themselves committed, with their own hands, for the crimes committed by them personally.”74 Justice, therefore, was meted out in Kharkov by the Soviet judges, albeit through the vehicle most familiar to Soviet jurists at the time, the Stalinist show trial.

The Aftermath

At the outset of the Kharkov trial, Ehrenburg wrote the following while sitting in the press box:

I waited a long time for this hour. I waited for it on the roads to France…. I waited for it in the villages of Belarussia, and in the cities of … Ukraine. I waited for the hour when these words would be heard: “The trial begins.” Today I heard them. The trial commences. On the dock, beside a traitor, three Germans. These are the first. But these are not the last. We will remember the 15th of December—on this day we stopped speaking about a future trial for the criminals. We began to judge them.75

Ehrenburg’s words did not come to pass. The Kharkov trial was not succeeded by other Soviet public trials of captured Nazis. After Kharkov, Stalin acceded to Churchill’s and Roosevelt’s request not to conduct any more high-profile prosecutions of captured Germans for fear that the Nazis would do the same to captured Western POWs. The documentary film of the trial was soon taken off Soviet screens.

For the rest of the war, the Soviets returned to their pre-Kharkov trial behavior of trying captured Nazis and collaborators in secret. The only evidence of such trials was their aftermath: the sudden appearance of gallows with dead men hanging from them.

After the war, the Soviet Union once again began publicly trying war criminals. The first postwar public trial took place in 1947, when ten low-ranking captured Germans were tried in the western Russian city of Smolensk. Other similar trials followed. Prusin notes: “As in the Krasnodar and Kharkov cases, the trials were held to pursue political and ideological objectives. The timing of the trials was chosen carefully to correspond with the Nuremberg Military Tribunal.”76 Sporadic trials of Nazis took place in the Soviet Union well into the 1960s. In total, it appears that the Soviets convicted approximately 25,000 German and Austrian Nazis, with most of the trials taking place within a few years after the end of the war.77

Additionally, over a million German POWs in the Soviet Union and other parts of Eastern Europe were used as laborers to rebuild the destruction that resulted from the war. Many of these men were not returned to Germany until many years after the war ended.78 It would not be until 1955 that the last surviving German POWs returned from the U.S.S.R.

Formation of Holocaust Memory in Soviet and Post-Soviet Eras

In the Soviet Union, immediately after the war, discussion of the mass murder of Soviet Jews during German occupation was repressed, as it had been during the war and at the Kharkov trial. According to Zvi Gitelman, “the term ‘Holocaust’ [was] completely unknown in the Soviet literature. In discussions of the destruction of the Jews, the terms unichtozhenie (‘annihilation’) or katastrofa (‘catastrophe’) [had] been used.”79 Gitelman adds: “It is only recently [as of 1997] that ‘Holocaust,’ transliterated from English [as Holocost/Xолокост]” appears in the public vocabulary.80

Gitelman provides a leading rationale behind the official Soviet policy of treating the suffering of all nationalities and ethnic groups in the Soviet Union under German occupation equally, encapsulated in the above-noted Soviet slogan “Do Not Divide the Dead”:

[N]o country in the West lost as many of its non-Jewish citizens in the war against Nazism as did the U.S.S.R., so that the fate of the Jews in France, Holland, Germany, or Belgium stands in sharper contrast to that of their co-nationals or co-religionists than it does in the East…. Thus the Soviet Union did treat the issue differently from the way it was treated in most other countries, whether socialist or not, though the Soviet treatment was not uniform … the Holocaust was seen as an integral part of a larger phenomenon—the murder of civilians—whether Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians, Gypsies, or other nationalities. It was said to be a natural consequence of racist fascism…. If the Nazis gave the Jews ‘special treatment,’ the Soviets would not.81

With respect to discussion of the Holocaust of Ukrainian Jews, Dawson explains: “It’s been said that history is written by the winners, but in the history of the Holocaust it’s as though the chapter on Ukraine had been written by Himmler himself. For all practical purposes, the pages are blank.”82 Dawson reflects:

The slaughter by gunfire in Ukraine should have become Hitler’s original sin and Babi Yar—where 34,000 Jews were murdered in two days—the darkest icon of the Shoah. But when the war ended, Stalin abetted Himmler’s cover-ups by throwing an Iron Curtain around his crime scene, off limits to writers, journalists, and historians. The only deaths in the Great War to defend the Motherland would be “Russian” deaths. And so, by default, the liberation of Auschwitz and other camps became the defining images of the Holocaust. Hitler’s crime in Ukraine began to fade slowly from public view and consciousness till it became what it is today—barely a footnote in popular understanding of the Holocaust. 83

After the war, some effort was made by Soviet Jews themselves to bring to light the suffering of the Jewish people at the hands of the Germans and local collaborators. In 1946, Soviet Jewish writers Ilya Ehrenberg and Vassily Grossman published the Black Book in the United States and other foreign countries. The Black Book became the “best source of primary material on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union,”84 but was banned from publication in the U.S.S.R. because, in the eyes of Soviet officials, it emphasized that “the Germans murdered and plundered Jews only. The reader unwittingly gets the impression that the Germans fought against the U.S.S.R. for the sole purpose of destroying Jews.” 85 The volume only made its appearance in Russia and the other former Soviet states in 1993, after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Despite attempts by Soviet officials to restrict the memory of the atrocities committed against the Jews during the war, Soviet Jews did attempt to commemorate their special suffering. One of the first gatherings to commemorate Holocaust victims took place in Kharkov in January 1945 to mark the anniversary of the Drobitsky Yar massacre. The Drobitsky Yar commemoration was an exception. Public commemoratory gatherings and burials became forbidden, though “appropriate institutions” such as synagogues were able to hold memorial services. According to Mordecai Altshuler: “[There is] evidence of extensive Jewish activity in the commemoration of Holocaust victims. Jews from various towns participated in these efforts, and religious circles and prominent figures in the Soviet establishment maintained cooperative relations in their joint endeavors.”86 This commemoration continued even when it was forbidden. Unlike in other European nations where commemoration was allowed, Soviet Jews had to make “strenuous efforts” and “maneuver among various Soviet authorities in order to implement, albeit partly and often unsuccessfully, even a few of their plans in this respect.”87

Finally, in 1991, with the fall of the Soviet Union, discussion of the “Holocaust” and access to the massive Soviet archives were finally allowed. Reference to the victims of the Holocaust as “Jews” in the monument for Babi Yar was made for the first time. The monument had not even been constructed until 1976, well after Yevgenii Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar” brought the world’s attention to the massacre (its opening words were: “No monument stands over Babi Yar”).

We noted above how the plaque installed in 2000 at the Kharkov Theater noting the trial makes no mention of Jews as victims. However, in 2002 a memorial was dedicated in the presence of Ukraine’s president, Leonid Kuchma, at Drobitsky Yar. A nine-foot-tall menorah stands beside the highway at Drobitsky Yar: “To one side, a tree-lined road winds to a massive white arch with the years ‘1941–1942’ framed in a circle on the outside and bright blue Stars of David within. Below the arch is a sculpture depicting the tablets of the Ten Commandments. ‘Thou Shall Not Kill’ [is] engraved in several languages, including Yiddish and Ukrainian.”88

And in 1996, the Kharkov Holocaust Museum opened in Kharkov. It contains an exhibit devoted to the murder campaign against the Jews and the trial at Kharkov in 1943, including photos, a documentary of the trials, and other archival materials. The museum remains “the only public Holocaust museum in Ukraine.”89