Читать книгу Terror Has No Diary - Michael Melnick - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

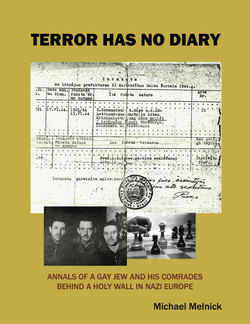

ОглавлениеYou die twice. First, when your brain turns off and your heart no longer beats; second, when not a soul on earth recalls your life, even your name or face. It is then that you are but a statistic in a government ledger, in a necrology, or on a faded cemetery headstone that receives no visitors. The Shoa sharply focused this almost universal reality. Europe is a vast unmarked Jewish graveyard, from Kiev to Amsterdam, from Hamburg to Salonika. The continuing tragedy is that relatively few can be rescued from a second, and final, death.

This cataclysm intensifies our obligation to those who survived as targets of the Germans and the local gentile populations that collaborated in and profited from the genocide of the Jews. That obligation is to permit survivors their memorial remnants with all the idiosyncratic nuances that cannot be gleaned from administrative documents. To “pierce the smugness of scholarly detachment,” as survivor-historian Saul Friedländer tells us. To bring the story to notice and allow us to infer. To tell it true.

The story you will read is my attempt to vivify a small number of the many Jews who resided in the Baltic seaport of Libau (Liepaja), to provide a forum for them to reveal their hopes, fears, and, most of all, their reactions to the destruction of their community. More than two decades ago, Aharon Appelfeld, survivor and Israeli literary lion, erected the guidepost: “Everything in [the Shoa] seems so thoroughly unreal, as if it no longer belongs to the experience of our generation, but to mythology. Thence comes the need to bring it down to the human realm….to attempt to make the events speak through the individual and in his language, to rescue the suffering from huge numbers, from dreadful anonymity, and to restore the person’s given and family name, to give the tortured person back his human form, which was snatched away from him”1

The outcome of my effort is solely my responsibility and is not to be construed to represent the views or beliefs of those who may have assisted me in any manner. In attempting to measure up to Appelfeld’s high bar, I have sometimes had to draw inferences from diaries, testimonies, and the like that may be wholly different from those that others might draw. To “give the tortured person back his human form” is neither simple nor without detractors, particularly those bewitched by the myth of objective historiography and/or repulsed by the Jewish tradition of transcendent history. Notwithstanding, I very much hope to have achieved some measure of success in distilling the truth of the matter from the facts of the matter. Still, whatever is contained in these pages, good or otherwise, is my responsibility and only mine.

****

First and foremost, I want to acknowledge the great generosity of Edward Anders, Professor Emeritus, University of Chicago. Professor Anders (né Alperovich), as a young man, survived the destruction of the Jewish community of Libau. He and his mother immigrated to New York City after Germany’s surrender; his father and brother did not survive. Over the past decade or so Professor Anders has dedicated a considerable portion of his life to documenting and memorializing the destruction of Libau’s Jews. He worked tirelessly to construct a memorial to the thousands who were murdered, a dignified monument prominently placed in the Jewish cemetery of Liepaja (Libau). Professor Anders has written and lectured extensively on Libau’s Jews, notably his memorial book “Jews in Liepaja, Latvia, 1941-1945” and his English translation of Josifs Steimanis’ “History of Latvian Jews.”

Most central to the book in hand, was Professor Anders’ great effort to make “The Diary of Kalman Linkimer” accessible to the English-speaking world. Initially translated from the Yiddish by Rebecca Margolis, Ed Anders edited the diary with care and sensitivity to produce “Nineteen Months in a Cellar: How 11 Jews Eluded Hitler’s Henchmen.” This was a frustrating effort for many reasons. First, Linkimer began the diary on the day of Germany’s invasion, left the diary behind when he escaped from Paplaka, and reconstructed it after he arrived at Sedols’ cellar. Second, the diary abruptly ends more than two months before liberation.Third, it appeared to Ms. Margolis, based on the uniform handwriting of the “original,” that the diary was rewritten, or at least recopied, sometime after liberation. Fourth, the diary is a diary: it is highly subjective and considerably stilted in its prose, with little to no narrative flow. As a consequence of all this, the English translation is an important primary source, but neither complete nor literary.

All this notwithstanding, unfettered use of Professor Anders’ English translation of Kalman Linkimer’s diary was invaluable to me in preparing the book in hand. I was deeply moved six years ago when Ed Anders offered me the opportunity, as he put it, “to prepare a shorter, more dramatic and faster-moving version of the diary that will have wider appeal.” Professor Anders, to be sure, bears no responsibility whatsoever for what appears in the book in hand. The present work is not an edited version of the edited English version. Rather, the diary is an important source among many other sources. Still, I shall always be indebted to Professor Anders for his offer and generous willingness to consign Linkimer’s story to an unknown telling.

I am most grateful to Ada Israeli (née Adinka Zivcon) and her husband, Yosef. They were my hosts in Israel, and made all the arrangements for my visits with Hilde Skutelsky and Aaron Vesterman. Ada and I have had many hours of conversation in person and by email about her mother, Riva Zivcon. In addition, she has provided very many of the photographs in the book. Most importantly, she was kind enough to read an earlier draft of the book and to encourage me over and over to completion. I am also grateful to Hilde and Aaron for hours of conversation that provided important facts and insights to events and personalities in the story. Aaron has also given me three key photographs, including the most moving picture in the book which he snapped clandestinely, that of the matronly women in the marketplace with square Jew patches sown on their dresses.

I am also grateful to my cousin Elias Hirschberg and his twin brother Jacob, the sons of Zelig Hirschberg, one of the eleven in the cellar. Elias spent a week acquainting me with Riga, its environs, and the countryside between Riga and Liepaja. In Liepaja, both Elias and Jacob helped me explore the city in detail, including a stop at 14 Kauf Street (now 22 Tirgonu). Together we made an emotional visit to Zelig’s grave and to those of our great grandparents, Meir and Beila Hirschberg. Elias and Jacob were invaluable in helping me put the events of the book in a physical and geographic context.

I wish to thank the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education, and to humbly acknowledge those whose interviews most informed the book in hand: Shoshana Kahn (née Rosa Sachs); Jeffrey Lowenson (né Efraim Levenson); Efraim “Fred” Neuburger; Max Solway (né Soloveichik). I thank my friend and colleague, Professor Abraham Yaari, who provided the initial rough translation of the previously untranslated Yiddish poems of Kalman Linkimer. I mostly wish to thank my scientific collaborator of 35 years, Professor Tina Jaskoll, for her invaluable assistance in preparing a complex manuscript.

To conclude, I thank Anita, my wife of 47 years. She has enthusiastically supported all my peregrinations save one – running with the bulls in Pamplona.

Michael Melnick

Professor

University of Southern California

January, 2013