Читать книгу Boy Giant - Michael Morpurgo - Страница 16

Оглавление

What ‘Gulliver’ meant I had no idea. Not then, anyway.

But from the way the old lady was talking and the way she was looking at me, the way they were all looking at me, I had the distinct feeling that I really was being welcomed home, as if I was some long-lost relative. The more I thought about it, the more I was sure that was who they believed I was. I must be ‘Gulliver’ – I was someone they all already knew and loved.

‘Gulliver! Gulliver!’

They were all shouting it out now, chanting it. I was some kind of a hero to these little people, to the children especially. Who they thought I was I could not imagine, nor did that bother me at all. I was quite happy to bask in such a joyous welcome. I responded by lifting my hands in the air and waving to them, which caused them to cheer and shout even louder. And then in amongst the chants of ‘Gulliver! Gulliver!’ I began to hear ‘Welcome, Gulliver. Owzat! Owzat!’

The more they chanted, the more I was sure they were using English words, spoken differently maybe, but definitely English words. It was the language of cricket, the language of aid workers in the camp. So, getting to my feet – and I was still unsteady at first – I raised my arms again and chanted back at them, ‘Gulliver! Gulliver! Owzat! Owzat!’

And then I thought of another word the aid workers in the refugee camp had taught me. ‘Hello!’ I shouted back. ‘Hello!’

I could tell from the delight on their faces that this was a word they knew, that they recognised, an English word. So this had to be England! And if I was in England, then Uncle Said and his café might not be far away. Mevagissey was not far away.

These people may be little, I thought, and all the doctors and aid workers I had known had been giants compared to them. But you could have ordinary-sized people and tiny people living in England, in the same country, couldn’t you? Why not? I told myself. I had arrived! I was safe and I was in England, where Mother had promised we would be. I had only to wait for her here, as she had said. Mother had been right about something else too. These English people were smiling people, welcoming people.

I was filled with relief, bursting with happiness. I punched the air again and again and cried out, ‘Owzat! Owzat!’

The tiny people were joining in, echoing every word. ‘Fore Street! Mevagissey! Four! Six! Not out! High five!’

Whenever I shouted out, punching the air, the name they had given me – ‘Gulliver! Gulliver!’ – they went wild. And they went wilder still when I began chanting ‘Owzat! Owzat!’

But then I noticed that the old lady was not joining in all this excitement. She was sitting there on her rock, looking up at me, her brow furrowed. She got to her feet then, and began to walk towards me, on the arm of her companion. I crouched down to be closer to her, holding out my hand in friendship. I was worried I had angered her somehow, and wanted to make it up to her.

She said nothing for a while, but was looking at me long and hard. Then she reached out and took my finger, gently drawing my hand towards her, so that she and her companion could step up on to it. Once they were balanced, I lifted them up very carefully, keeping my hand steady, so that they would not fall over. We were face to face now. The crowd had fallen quite silent.

The old lady and her companion were standing side by side in the palm of my hand. There was no fear in their eyes, only intense curiosity. Beckoning me closer she reached out her hand to touch my face. Then she was brushing the hair away from my forehead. A sudden smile came over her.

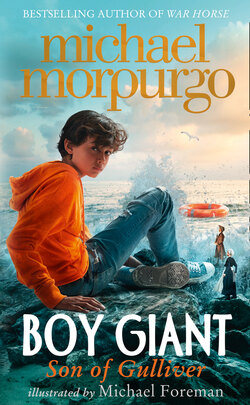

‘Not Gulliver,’ she said softly. ‘Son of Gulliver.’ Then she turned and proclaimed it out loud to the crowd. ‘Son of Gulliver! He is Son of Gulliver!’

There was a gasp of amazement at this, from all around. So now I was a son of this Gulliver. And I knew what ‘son’ meant. One of the aid workers in the refugee camp – Jimbo he was called – had shown me photographs on his phone of a boy about my age, obviously his son, holding a cricket bat – he liked cricket too, and Jimbo was the one who used to call me ‘son’. ‘Hello, son,’ he’d say to me sometimes. ‘You all right, son?’

So now I was ‘Son of Gulliver’. I could think of nothing else to do but look as pleased as the old lady was, as her companion was, as everyone seemed to be. I called out, ‘Son of Gulliver! Son of Gulliver! Owzat!’

The old lady seemed happy with that. They all were, so I thought I must have said the right thing.

From then on, that’s who I was to these people, ‘Son of Gulliver!’ But the children usually preferred to call me Owzat. I still did not understand who Gulliver was, nor why I should be his son. That, and everything else about this strange place, which had to be England – I was sure of it by now – was still a complete mystery to me. But I did not mind this, nor how confusing and strange everything was.

Another confusion was the language they spoke. I had already heard many of them speaking amongst themselves in another language that did not sound at all like English. So they must speak in two languages. Strange again, but what did it matter? All I knew was that I was amongst people who were kind, and I was safe. What else could matter?

But something else did matter. I was suddenly feeling weak with hunger and I was dying of thirst.