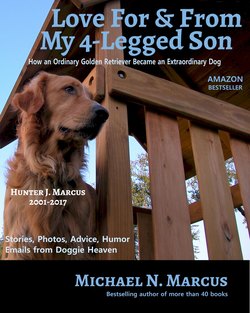

Читать книгу Love For & From My 4-Legged Son: How an ordinary golden retriever became an extraordinary dog - Michael N Marcus - Страница 5

Introduction

ОглавлениеHunter J. Marcus (my “four-legged son”) lived for fifteen years and three months. He was a golden retriever and the typical lifespan for a “golden” is ten to twelve years, so he definitely had high mileage.

His death was not violent, sudden nor unexpected—but was nonetheless tragic.

I could not be more miserable because of the loss of a human child.

I never thought of Hunter as a pet, and certainly not as a possession. He was a housemate, child, playmate, co-conspirator, fellow traveler, and—most of all—my best buddy.

I used to say that Hunter soared like an eagle, swam like a porpoise, ate like a shark and often thought like a human.

However, Hunter did not win any ribbons or trophies. He was not a superstar. He had no special training. As a baby he was not chosen because of his famous parents. He was not a great runner, jumper, fetcher or even a great hunter.

He could, however, climb a ladder, slide down a slide, count, and read The New York Times upside-down!

Hunter understood dozens of English words and was very obedient—when he chose to be.

Golden retrievers are very smart, and very independent. Hunter knew exactly what he was supposed to do in any situation—and sometimes he was willing to do what he was supposed to do.

Some might say he was obstinate. I prefer to say he was a free-thinker. He could sometimes be controlled by a leash, but he never responded to begging, negotiating or arguing. The most effective motivator was food. Hunter understood rewards and trades.

I did not name him Hunter—his first human family did that—and I did not want to confuse him with a name change. I’m a peaceable person. I don’t hunt or like guns but it did not bother me to live with a Hunter.

Hunter’s middle initial does not represent a middle name. It’s an homage to my maternal grandfather, Dr. Jay N. Jacobs. He had no middle name but Grandma Del thought a middle initial made his business cards more impressive.

I used to explain Hunter’s name by saying that he hunts for food and friends and anyone who gives him food instantly becomes a friend. Some dogs and people are very picky eaters but Hunter never rejected a meal or a snack. (Fortunately he never ate a dead bird or a “poopsicle.”)

In most ways Hunter was a very ordinary dog. But an ordinary dog can be extraordinary. Genes are important, but, as with people, a dog’s family can make a big difference.

When a canine joins a Homo Sapiens family the dog brings millennia of evolution with it. Its personality and abilities reflect countless generations of earlier animals.

But still, in many ways a pup is a blank slate (“tabula rasa” in Latin). A dog can be taught a lot, and can even become self-taught (“autodidactic”).

A dog’s amazing senses allow it to observe and analyze the creatures she or he lives with. Your pooch may decide to copy some human rituals, and can learn the meaning of and the proper response to words that you never tried to teach. (Hunter figured out that “excuse me” means “please get out of my way.”)

A dog may learn to do tricks even without repetition or the reinforcement provided to Pavlov’s dogs.

In Time magazine, Justin Worland wrote: “Neurology research has shown that mammals possess the same brain chemicals that give humans self-awareness. Behavioral studies have demonstrated that some species experience social relations previously not understood.”

When I was a teenager our home was shared with Sniffer, a cocker spaniel-golden retriever mix. “Sniffy” (his nickname) was smart, observant and highly anthropomorphic. He copied human activities and may have even thought he was human.

Sniffy had learned to slap when play-fighting with human beings. When he got into a fight with another dog his initial impulse was to slap with his ‘hands.’ It was unproductive.

Then he’d recognize the presence of his opponent’s tail, four legs and sharp teeth and re-evaluate his strategy. He’d withdraw and assume a traditional canine battle stance—growling and biting.

In the morning Sniffy’d go outside, cross the street and knock on the front door of the Cohens’ house. When Poochie Cohen came out, Sniffy and Poochie would go down the block and knock on the Gordons’ door so Buttons Gordon would come out and play. The dogs were mimicking the behavior of the human children in the neighborhood. But no one had taught them or bribed them to do it.

Hunter and I often bathed together in our Jacuzzi-like tub. (The photo shows nephew Joe assisting.) The first time we did this I washed his right side and then said “turn around.” He immediately turned around so I could clean his left side—even though I had no reason to expect him to know what “turn around” meant.

When Hunter was young we often took a morning walk of nearly a mile. One day when we had gone about a quarter of the way, it started raining. The sky quickly darkened and I saw lightning and heard thunder. I said to Hunter something like “we’d better go back now.” I had never before tried to teach him how to respond to “go back” but he instantly made a U-turn and headed for home.

Just as parrots may unexpectedly talk dirty—saying words they heard but were not taught—a dog may surprise you by mimicking you. Be careful what you do. Set a good example.

I’ve often said that every human being is born with a unique set of abilities and it is our obligation to find a market for those abilities.

Similarly, canines and young Homo Sapiens have amazing capabilities that adult humans may not give them credit for. I believe in setting a “high bar” to encourage striving and achieving (with love and rewards, of course). I always use adult English—never baby talk—when speaking to a human baby or a non-human of any age. I’ve never said “me go bye-bye” and hope I never will.

In a way, it seems strange to refer to Hunter as my dog, as if I owned him—like my iPad. Hunter was a live being capable of independent thought (sometimes much too independent), and not my possession. However, since I speak of “my wife” or “my friend,” Hunter was “my dog.”

Just as I don’t believe in racism, sexism or ageism, I don’t believe in speciesism. All mammals have full rights and privileges in our home. If Hunter wanted to nap on a couch or on the kitchen table or eat on our bed—that was his right and we never complained.

Hunter got away with a lot. Wife Marilyn and I rewarded bad behavior because Hunter was a perpetual puppy and we considered that everything he did was cute. We have no human kids so Hunter got—and returned—a lot of love.

Hunter was the ultimate SBD (silent-but-deadly) farter. His farts smelled as bad as his poop, but I never heard him fart—even once. His butt was a stealth weapon, striking with no warning.

Despite the occasional stink bomb, dogs have advantages over human kids. No bad report cards. No bar/bat mitzvahs, college or weddings to pay for. I just picked up poop. I also paid for Hunter’s castration—not necessary for human sons.

For humans a blizzard is often misery

For goldens, it’s ecstasy.