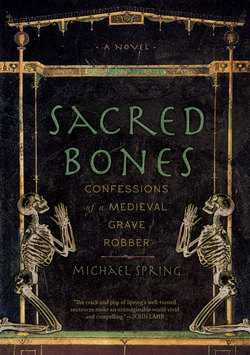

Читать книгу Sacred Bones - Michael Spring - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNINE

One moonless night, near my thirteenth birth day, a voice came to me in bed, advising me to leave the library and serve God in the catacombs. There are seven cemeterial districts in Rome. I was appointed assistant to the deacon in charge of the third, an area encompassing the Prenestina, Tibertina, and Labicana. The catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus was in the Labicana.

It was my job to lead dignitaries and groups of pilgrims through the ancient passages and pray with them at the holiest shrines. Guidebooks and itineraries were useless here; visitors were lost without me. I felt a rush of pleasure as I led them down the dark, damp corridors. Sinners and sycophants, abbots and acolytes, merchants and thieves—everyone clustered around my light.

I spent my free time trying to preserve this crumbling world. I filled fonts with holy water, and lamps with sweet-smelling oils. I broke off the roots of trees that were growing down through the ceilings, cracking plaster, destroying priceless paintings, and wrapping themselves around the bones of our holiest protectors. I swept up dead rodents and cleared walkways choked with rubbish. People said that jackals and wolves lived here, but I never saw one. Several times I stumbled on a debtor or thief who made his home in an abandoned chapel, but they were always more frightened than I was, and scurried off into the darkness.

It was in one of the Jewish catacombs, standing among the circumcised dead, that I fornicated with myself. I was sure that, like Onan, I would be struck down for spilling my seed, but God is merciful and He let me earn forgiveness on a diet of stale bread and water.

I also defiled myself in my sleep, but this was not a sin, as we have no defense against the devil when we are sleeping. When the urge to sully myself returned, I denied myself, thanks to God. No land can bear fruit which in a single year is frequently sown, sacred scripture tells us, so why would we do to our bodies what we wouldn’t do to our own fields?

At about this time I began selling amulets to believers, which they wore around their necks to guard against sickness and death. The most popular were lead badges, which are still sold in the shrines, engraved with the image of Christ mounted on a horse, bearing a cross. Pilgrims couldn’t get enough of them, so I bought a large supply from a Greek priest and sold them at a hefty profit. I donated my first piece of silver to the poor. With the second I bought a bag of pistachios.

I also sold priceless guidebooks to the wealthiest pilgrims, who, in their ignorance, believed a visit to a shrine increased the chances of eternal life. “The only guide you need is faith,” I wanted to say. “The journey to God is inward. You can also find Him without leaving home.”

To bring light to a dark world, and to make a living, I swept dust from the holy tombs into tiny cloth packets and sold them to pilgrims. I also sold strips of sanctified cloth that had touched the relics, and vials of lamp oil that lit the chapels.

Some believers pressed coins into my hands, often their life savings, hoping to purchase a sliver of bone or a pinch of holy dust that would open the gates of heaven. I always turned them down. Monks tried to bribe me with prayers and the promise of eternal life, but I ignored them, too. Rome’s holiest protectors were not for sale. I guarded them as a man guards his family from murderers and thieves.

Though I would never deliberately sell a sacred bone, I did over time agree to part with some of the holy objects that were identified with, or had come in touch with, the saints and martyrs.

I sold three drops of blood from the Crucifixion to a pious baker from the Low Country, and his barren wife gave birth to a child before he returned home. Pilgrims from Ireland bought angel meat from me by the pound, and spread it on the ground, resulting in a bumper crop of vetches. A bearded Frisian bought a spoonful of the manna God gave the Israelites in the wilderness. The Franks took whatever I offered them: pieces of the clay from which God shaped Adam, slivers of Aaron’s rod, thorns from the holy crown.

I once sold a Spanish abbot a chipped water pot that was used at Cana, strands of the Virgin’s hair in shades of red, black, brown, and yellow, and enough of the Virgin Mother’s milk to feed a baby for a year. God rewarded me with a good living and excellent health.

Nothing was in greater demand than wood from the Cross. Buyers could be very demanding, though. An old Semite from Jerusalem once sent back a stick of boxwood, insisting that the True Cross was made of palm. He cursed me in God’s name.