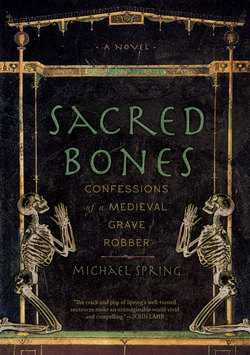

Читать книгу Sacred Bones - Michael Spring - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

Deusdona is the name I go by. “God’s gift.” I’d prefer the name of a Roman senator: Publius, say, or Marcius—someone who gave his life to public service back in the days of the Republic, when Rome was the center of the world, not Aachen. But you can’t improve on Deusdona, not if you make a living buying and selling sacred bones. It’s a name that has given me instant credibility in a competitive field, and helped me grow my business.

My real name is buried with my mother, who died bringing me into the world, and with my father, who disappeared under a new moon in the year of the Great Flood. More than forty winters later, I still wake in the night and see the waters bursting through the Flaminian Gates, ripping them from their hinges, sweeping over the walls to the foot of the Capitoline Hill. My father leans against a toppled pillar near the Forum, enjoying the sonorities of Virgil’s Georgics, when suddenly the waters engulf him. He calls out a name, but all I can hear are the rushing waters.

Neighbors brought me to the orphanage at Saint Peter’s, where I grew up in the company of monks and priests. They still visit me in my sleep. I see their pale, eager faces peering out at me from behind their hoods, and feel the terrible sweetness of their touch.

I longed to be educated in the Lateran with the cubicularii, in personal attendance on the pope, but that was a preferment reserved for the sons of the wealthy. I was sent instead to a school for priests, in the glow of Saint Peter’s, outside the city walls. I was only seven, but I was sure God was banishing me for my sins. Exile could not have been a harsher punishment. Years passed before I understood that God wanted me to grow up in Peter’s presence, at the spiritual heart of the Church. The Lateran occupied a green and airy site, surrounded by gardens and vineyards. It was gifted to the Church by Constantine himself. But the pope was isolated there with his scribes and legates, away from the people. When pilgrims arrived in Rome, it was Peter’s bones, not the pope’s, they went to see. Our current Father, Gregory, still has to cross town to celebrate High Mass. It’s a wonderful procession, but each time he passes I want to shout out, “You’re the Keeper of the Keys of Heaven and Hell, not just the bishop of a powerful See. Move closer to Peter’s rock and leave the Lateran to the sheep and vines.” It’s a wonder God hasn’t struck me down for my impertinence.

• 800 AD •

I had my first glimpse of a pope on a bitingly cold spring morning, when Leo rode from the Lateran to the Holy See for the Festival of Saint Mark. Leo was a foreigner, the son of Atyuppius—a Saracen or Slav. He had tricked some virgins into drinking pig’s blood from the holy chalice and one of them had given birth to an aurochs with horns. Still, he was Peter’s successor, a man intimate with God. His face, I assumed, must radiate a wonderful light.

I had no father to hoist me on his shoulders above the towering Lombards, so I left my dorm before dawn, when the city still belonged to the devil, crossed the river, and made my way through the silent streets to the monastery church of Saints Stephen and Silvester. From here, I could watch the Holy Father as he rode to the old Church of Saint Lorenzo. It was here the formal procession began.

The air was nippy. I relaxed my muscles and told myself I wasn’t cold. The pure young voices of the choirboys floated on the morning air, lifting me to a world beyond care. I was about to slip into the church when I heard the distant singing of the Kyrie Eleison. The public seldom joined in, but today was different.

The poor from the hospitals came first, niddle-noddling along the broken streets, holding their painted wooden crosses above their heads. Boys my age came next, followed by the clerical officers and acolytes, the chief officer of the guards, and the regional notaries. Some of them were draped in the silky white robes that Roman officers wore in the days of the Empire.

“Lord have mercy on us,” they sang.

“Lord have mercy on us,” we cried back.

Then I saw him, the Supreme Pontiff, the Nourisher of the One Immaculate Dove, slouching forward on a large brown horse. As he passed by—so close we could almost touch—the mount in front of him stopped to drop a load, and Leo’s horse drew up short. The Pope lurched forward and grabbed the animal’s mane to keep from falling. I saw his small pouting mouth, his thin tight lips, his narrow shoulders. I thought his eyes would be shining with God’s light, but they were black and empty. I expected to behold the power and the glory, but all I saw was an old man clinging to a startled horse.

Suddenly, a gang of ruffians rushed out from the church, brandishing knives and heavy sticks. The crowd screamed and scattered. The Pope’s unarmed guards whirled about on their frightened horses. Leo was seized from his mount and thrown down on the paving stones. No one tried to save him. His face was ripped open. I wanted to wave a sword and shout, “It’s me, Augustus,” but all I did was stand and watch. And then, God forgive me, I wanted to pummel him, too, this man with terror in his eyes, who feared death more than he loved life; I wanted to slam my fist in his face. As his supporters dragged him into the church, I drew a finger through his blood pooling on the paving stones, and wiped it on my lips. Surely I’m damned, I thought. There is no penance great enough for this.

What Leo’s enemies had in store for him I’ll never know, because that same night he was lowered by ropes into the arms of the waiting chamberlain and carried to Saint Peter’s. Two of King Charles’s representatives were in residence there, investigating accusations of adultery and incompetence against the Pope, and one of them set off for Aachen immediately with his wounded charge.

I lay awake that night, among the sleeping boys, struggling with the truth of what I had seen. If the Pope was God’s elect, why had God abandoned him? Was it because Leo had fornicated with the devil?

I awoke, moaning for help. Cocks were crowing. I bolted up and thought, “If Leo’s guards had been armed, he would have been spared. God is our strength and our shield, but it helps to have a sword.”

I lay back, exhausted. I had touched some deep, abiding truth and, cradling it tightly, I fell into a deep, abiding sleep. I was still sleeping when the bells rang for Prime. I dressed quickly and ran to catch up with the others.