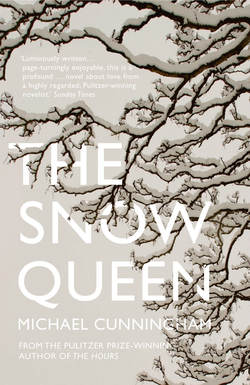

Читать книгу The Snow Queen - Michael Cunningham - Страница 10

ОглавлениеIt’s snowing in Tyler and Beth’s bedroom. Flecks of snow—tough little ice balls, more BB than flake, more gray than white in the early morning dimness—swirl onto the floorboards and the foot of the bed.

Tyler awakens from a dream, which dissolves almost entirely, leaving only a sensation of queasy and peevish joy. When he opens his eyes it seems, for a moment, that the skeins of snow blowing around the room are part of his dream, a manifestation of icy and divine mercy. But it is in fact real snow, blowing in through the window he and Beth left open last night.

Beth sleeps curled into the circle of Tyler’s arm. He gently disengages himself, gets up to close the window. He walks barefoot across the snow-sparkled floor, doing what needs to be done. This is satisfying. He’s the sensible one. In Beth, he has finally found someone more romantically impractical than he. Beth, if she woke, would, in all likelihood, ask him to leave the window open. She’d like the idea of their cramped, crowded little bedroom (the books pile up, and Beth won’t shed her habit of bringing home treasures she finds on the streets—the hula-girl lamp that could, in theory, be rewired; the battered leather suitcase; the two spindly, maidenly chairs) as a life-size snow globe.

Tyler shuts the window, with effort. Everything in this apartment is warped. A marble dropped in the middle of the living room would roll right out the front door. As he forces the sash down, a final fury of snow blows in, as if seeking its last chance at … what? … the annihilating warmth of Tyler and Beth’s bedroom, this brief offer of heat and dissolution? … As the miniature flurry blasts over him, a cinder blows into his eye; or maybe some obdurate microscopic ice crystal, like the tiniest imaginable sliver of glass. Tyler rubs his eye, can’t seem to get at the speck that’s embedded itself there. It’s as if he’s been subjected to a minor mutation; as if the clear speck had attached itself to his cornea, and so he stands with one eye clear and one bleary and watering, watching the snowflakes hurl themselves against the glass. It’s barely six o’clock. It’s white outside, everywhere. The elderly snow-piles that have been, day after day, plowed to the edges of the next-door parking—that have solidified into miniature gray mountains, touched toxically, here and there, with spangles of soot—are now, for now, alpine, like something out of a Christmas card; or, rather, something out of a Christmas card if you focus tightly, edit out the cocoa-colored, concrete facade of the empty warehouse (upon which the ghost of the word “concrete” is still emblazoned, although grown so faint it’s as if the building itself, so long neglected, still insists on announcing its own name) and the still-slumbering street where the neon q in the liquor sign winks and buzzes like a distress flare. Even in this tawdry cityscape, though—this haunted, half-empty neighborhood, where the burned carcass of an old Buick has remained (strangely pious in its rusted-out, gutted and graffitied, absolute uselessness) for the last year, on the street beneath Tyler’s window—there’s a gaunt beauty summoned by the pre-dawn light; a sense of compromised but still-living hope. Even in Bushwick. Here’s a fall of new snow, serious snow, immaculate, with its hint of benediction, as if some company that delivers hush and accord to the better neighborhoods had gotten the wrong address.

If you live in certain places, in a certain way, you’d better learn to praise the small felicities.

And, living as Tyler does in this place, in this placidly impoverished neighborhood of elderly aluminum siding, of warehouses and parking lots, all utilitarian, all built on the cheap, with its just-barely-managing little businesses and its daunted denizens (Dominicans, mostly, people who went to considerable effort to get here—who had, must have had, higher hopes than those that Bushwick has granted them) trudging dutifully along to or from minimum-wage jobs—as if defeat could no longer be defeated, as if one were lucky to have anything at all. It isn’t even particularly dangerous anymore; there is of course the occasional robbery but it seems, for the most part, that even the criminals have lost their ambition. In a place like this, praise is elusive. It’s difficult to stand at a window, watching snow feather onto the overflowing garbage cans (the garbage trucks seem to remember, sporadically, unpredictably, that there’s garbage to collect here, too) and the cracked cobblestones, without thinking ahead to its devolution into dun-colored sludge, the brown tarns of ankle-deep street-corner puddles upon which cigarette butts and balls of foil gum wrappers (fool’s silver) will float.

Tyler should go back to bed. Another interlude of sleep and who knows, he might wake into a world of more advanced, resolute cleanliness, a world wearing a still-heavier white blanket over its bedrock of drudgery and ash.

He’s reluctant, however, to leave the window in this condition of sludgy wistfulness. Going back to bed now would be too much like seeing a delicately emotional stage play that comes to neither a tragic nor happy ending, that begins to sputter out until there are no more actors onstage, until the audience realizes that the play must be over, that it’s time to get up and leave the theater.

Tyler has promised he’ll cut down. He’s been good about it, for the past couple of days. But now, right now, it’s a minor metaphysical emergency. Beth isn’t worse, but she isn’t better, either. Knickerbocker Avenue is waiting patiently through its brief interlude of accidental beauty until it can return to the slush and puddle that is its natural state.

All right. This morning, he’ll give himself a break. He can re-summon his rigor easily enough. This is only a boost, at a time when a boost is needed.

He goes to the nightstand, takes his vial from the drawer, and sucks up a couple of quick ones.

And here it is. Here’s the sting of livingness. He’s back after his nightly voyage of sleep, all clarity and purpose; he’s renewed his citizenship in the world of people who strive and connect, people who mean business, people who burn and want, who remember everything, who walk lucid and unafraid.

He returns to the window. If that windblown ice crystal meant to weld itself to his eye, the transformation is already complete; he can see more clearly now with the aid of this minuscule magnifying mirror …

Here’s Knickerbocker Avenue again, and, yes, it will soon return to its ongoing condition of anywhereness, it’s not as if Tyler has forgotten that, but the grimy impending future doesn’t matter, in very much the way Beth says that morphine doesn’t eradicate the pain but puts it aside, renders it unimportant, a sideshow curiosity, mortifying (See the Snake Boy! See the Bearded Lady!) but remote and, of course, a hoax, just spirit gum and latex.

Tyler’s own, lesser pain, the dampness of his inner workings, all those wires that hiss and spark in his brain, has been snapped dry by the coke. A moment ago, he was fuzzed out and mordant, but now—quick suck of harsh magic—he’s all acuity and verve. He’s shed his own costume, and the true suit of himself fits him perfectly. Tyler is a one-man audience, standing naked at a window at the start of the twenty-first century, with hope clattering in his rib cage. It seems possible that all the surprises (he didn’t exactly plan on being an unknown musician at forty-three, living in eroticized chastity with his dying girlfriend and his younger brother, who has turned, by slow degrees, from a young wizard into a tired middle-aged magician, summoning doves out of a hat for the ten thousandth time) have been part of an inscrutable effort, too immense to see; some accumulation of lost chances and canceled plans and girls who were almost but not quite, all of which seemed random at the time but have brought him here, to this window, to his difficult but interesting life, his bulldoggish loves, his still-taut belly (the drugs help) and jut of dick (his own) as the Republicans are about to go down and a new world, cold and clean, is set to begin.

Tyler will get a rag and wipe the melted snow off the floorboards. He will take care of it. He will adore Beth and Barrett with more purity. He will gather and procure, take on an extra shift at the bar, praise the snow and all it touches. He will get them out of this grim apartment, sing ferociously into the heart of the world, find an agent, stitch it all together, remember to soak the beans for cassoulet, get Beth to chemo on time, do less coke and cut out Dilaudid entirely, finally finish reading The Scarlet and the Black. He will hold Beth and Barrett, console them, remind them of how little there is to worry about, feed them, tell them the stories that render them that much more visible to themselves.

Outside, the snow shifts with a shift in the wind, and it seems as if some benign force, some vast invisible watcher, has known what Tyler wanted, the moment before he knew it himself—a sudden animation, a change, the gentle steady snowfall taken up and turned into fluttering sheets, an airy map of the wind currents; and yes—are you ready, Tyler?—it’s time to release the pigeons, five of them, from the liquor store roof, time to set them aflight and then (are you watching?) turn them, silvered by early light, counter to the windblown flakes, sail them effortlessly west into the agitated air that’s blowing the snow toward the East River (where barges will be plowing, whitened like ships of ice, through the choppy water); and yes, right, a moment later it’s time to turn the streetlights off and, simultaneously, bring a truck around the corner of Rock Street, its headlights still on and its flat silver top blinking little warning lights, garnet and ruby, that’s perfect, that’s amazing, thank you.