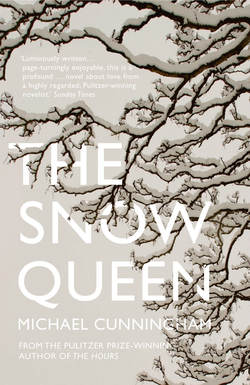

Читать книгу The Snow Queen - Michael Cunningham - Страница 11

ОглавлениеBarrett runs shirtless through the snow flurries. His chest is scarlet; his breath explodes in steam-puffs. He’s slept for a few agitated hours. Now he’s going for his morning run. He finds that he’s comforted by this utterly usual act, sprinting along Knickerbocker, leaving behind a small, quickly evaporating trail of his own exhalations, like a locomotive rumbling through some still-slumbering, snow-decked town, though Bushwick feels like an actual town, subject to a town’s structural logic (as opposed to its true condition of random buildings and rubble-strewn vacant lots, possessed of neither center nor outskirts), only at daybreak, only in its gelid hush, which is soon to end. Soon the delis and shops will open on Flushing, car horns will bleat, the deranged man—filthy and oracular, glowing with insanity like some of the more livid and mortified saints—will take up his station, with a sentry’s diligence, on the corner of Knickerbocker and Rock. But at the moment, for the moment, it’s actually quiet. Knickerbocker is muffled and nascent and dreamless, empty except for a few cars crawling cautiously along, cutting their headlights into the falling snow.

It’s been coming down since midnight. Snow eddies and tumbles as the point of equinox passes, and the sky starts all but imperceptibly turning from its nocturnal blackish brown to the lucid velvety gray of first morning, New York’s only innocent sky.

Last night the sky awakened, opened an eye, and saw neither more nor less than Barrett Meeks, homeward bound in a Cossack-style overcoat, standing on the icy platter of Central Park. The sky regarded him, noted him, closed its eye again, and returned to what were, as Barrett can only imagine, more revelatory, incandescent, galaxy-wheeling dreams.

A fear: last night was nothing, a blip, an accidental glimpse behind a celestial curtain, just one of those things. Barrett was no more “chosen” than an upstairs maid would be destined to marry into the family because she happened to see the eldest son naked, on his way to his bath, when he’d assumed the hall to be empty.

Another fear: last night was something, but it’s impossible to know, or even guess at, what. Barrett, a perverse, wrong-headed Catholic even in his grade school days (the gray-veined marble Christ at the entrance to the Transfiguration School was hot, he had a six-pack and biceps and that mournful, maidenly face), can’t remember being told, not even by the most despairing of the nuns, of a vision delivered so arbitrarily, so absent of context. Visions are answers. Answers imply questions.

It’s not as if Barrett lacks questions. Who does? But nothing much that begs response from prophet or oracle. Even if the chance were offered, would he want a disciple to run sock-footed down a dim and flickering corridor to interrupt the seer for the purpose of asking, Why do Barrett Meeks’s boyfriends all turn out to be sadistic dweebs? Or, What occupation will finally hold Barrett’s interest for longer than six months?

What, then—if intention was expressed last night, if that celestial eye opened specifically for Barrett—was the annunciation? What exactly did the light want him to go forth and do?

When he got home, he asked Tyler if he’d seen it (Beth was in bed, held in orbit by the increasing gravitational pull of her twilight zone). When Tyler said, “Seen what?” Barrett found, to his surprise, that he was reluctant to say anything about the light. There was of course the obvious explanation—who wants his older brother to suspect he’s delusional?—but there was as well a more peculiar sense, for Barrett, of a need for discretion, as if he’d been silently instructed to tell no one. So he made up something quick, about a hit-and-run on the corner of Thames Street.

And then he checked the news.

Nothing. The election, of course. And the fact that Arafat is dying; that the torture at Guantánamo has been confirmed; that a much-anticipated space capsule containing samples taken from the sun has crashed, because its parachute failed to open.

But no lantern-jawed newscaster locked eyes with the camera and said, This evening the eye of God looked down upon the earth …

Barrett made dinner (Tyler can’t be counted on these days to remember that people need to eat periodically, and Beth is too ill). He allowed himself to return to wondering about this last, lost love. Maybe it was that late-night phone conversation, when Barrett knew he was going on too long about the deranged customer who’d insisted that, before he bought a particular jacket, he’d need proof that it had been made under cruelty-free conditions—Barrett can be a bore sometimes, right?—or maybe it was the night he hit the cue ball right off the table, and the lesbian made that remark to her girlfriend (he can be an embarrassment sometimes, too).

He could not, however, contemplate his mysterious misdeeds for long. He’d seen something impossible. Something that, apparently, no one else saw.

He made dinner. He tried to continue compiling his list of reasons for having been dumped.

Now, the following morning, he’s going for his run. Why wouldn’t he?

As he leaps over a frozen puddle at the corner of Knickerbocker and Thames, the streetlights turn themselves off. Now that a very different light has shown itself to him, he finds himself imagining some connection between the leap and the extinguishment, as if he, Barrett, had ordered the streetlights dimmed, by jumping. As if a lone man, out for his regular three miles, could be the instigator of the new day.

There’s that difference, between yesterday and today.