Читать книгу Erebus - Michael Palin - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

MAGNETIC NORTH

If the years in which Erebus patrolled the Mediterranean were ones of comparative idleness for the Royal Navy, there were certain benefits. Press gangs became a thing of the past. Men could choose their ships. The Navy became more specialised, more professional. And with the Napoleonic Wars over, a non-militaristic area of maritime activity started to open up, offering opportunities for the able, the adventurous and the better-qualified to use Britain’s naval superiority to pursue new goals: to extend man’s geographical and scientific knowledge by exploration and discovery.

The impetus for this new direction came largely from two remarkable men. One was the polymath Joseph Banks, the embodiment of the Enlightenment. An author and traveller, botanist and natural historian, Banks had circumnavigated the globe with Captain Cook in 1768, bringing back a huge amount of scientific information as well as mapping previously unknown corners of the planet. The other was one of Banks’s protégés, John Barrow, an energetic and ambitious civil servant, who in 1804, at the age of forty, had been appointed Second Secretary at the Admiralty.

Barrow and Banks formed around them a circle of enterprising scientists and navigators. Much inspired by the work of the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, their aim was to assist an international effort to chart, record and label the planet, its geography, natural history, zoology and botany. They were to set the agenda for a golden period of British exploration, motivated more by scientific enquiry than by military glory.

Barrow’s priority was the partly explored Arctic region. Ever since John Cabot, an Italian who settled in Bristol, had discovered Newfoundland in 1497, there had been keen interest in discovering whether there might be a northern route to ‘Cathay’ (China) and the Indies to compete with the southern route via Cape Horn (dominated at that time by the Spanish and Portuguese). From his desk at the Admiralty, John Barrow championed the cause, using every conceivable contact and pursuing every line of influence to make it happen. If the Navy could discover a Northwest Passage linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, he argued, the advantages to Britain in terms of safer and shorter journeys to and from the lucrative East would be immense.

Around 1815, the year of Waterloo, whalers – the forgotten men of polar exploration, but the only ones to keep a regular eye on Arctic and Antarctic waters – returned from the north with reports of the ice breaking up around Greenland. One of them, William Scoresby, was of the opinion that if one could get through the ice-pack that lay between latitudes 70 and 80°N, there was clear water all the way to the Pole, offering the tantalising prospect of a sea passage to the Pacific. He backed this up with evidence of whales harpooned off Greenland appearing, with the harpoons still in their sides, south of the Bering Strait.

Barrow, attracted by the idea of an ice-free polar sea, persuaded the Royal Society to set a sliding scale of rewards for penetration into Arctic waters. These ranged from £5,000 for the first vessel to reach 110°W, to a £20,000 jackpot for discovering the Northwest Passage itself. With the backing of Sir Joseph Banks, he then approached the First Lord of the Admiralty, Robert Dundas, 2nd Viscount Melville, along with the Royal Society, with a view to commissioning two publicly funded Arctic expeditions: one to search for a sea passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the other to make for the North Pole to investigate the reports of clear water beyond the ice.

For Robert Dundas, this suggestion must have seemed a heaven-sent opportunity. A Scot whose father had enjoyed the dubious distinction of being the first minister ever to be impeached for misusing public funds, he had been at the Admiralty for six years, where he had spent much of his time resisting cuts to the Navy. Barrow’s proposals offered a means of keeping some existing ships busy, and thus fending off any criticism that the Navy had considerably more than it knew what to do with. He therefore took kindly to Barrow’s new proposals.

To lead one of the expeditions the Admiralty turned to a Scottish mariner, John Ross. The third son of the Reverend Andrew Ross, he came from a family who lived near the town of Stranraer in Wigtownshire, whose fine natural harbour would have been a regular port of call for Royal Navy vessels. It was common then for families to let their children join the Navy as part of their general schooling, and John had joined up as a First-Class Volunteer at the age of nine. By the time he was thirteen he had been transferred to the 98-gun warship Impregnable. A distinguished career, in and out of battle, followed. In late 1818, when he received the letter appointing him leader of the Admiralty-backed expedition to search for the Northwest Passage, he was forty years old, well regarded and had spent most of his life in service.

Ross was given command of HMS Isabella and proceeded to use a little nepotism to bring on board his eighteen-year-old nephew, James Ross. Inspired and encouraged by his uncle’s example, James had joined the Navy at the age of eleven, and had served an apprenticeship under his uncle in the Baltic and the White Sea, off northern Russia. He joined Isabella as a midshipman, traditionally the first step to becoming a commissioned officer.

James was tall and well built, and his education in the Navy had served him well. He had learned a lot about the latest scientific advances, especially in the field of navigation and geomagnetism. The ability to understand and harness the earth’s magnetic forces was one of the great prizes of science in the early nineteenth century, and one in which James Clark Ross (he added the ‘Clark’ later, to distinguish himself from his uncle) was to become intimately involved.

In charge of HMS Trent, one of the ships entrusted with reaching the North Pole, was another career sailor, thirty-two-year-old John Franklin. Like John Ross, he had seen action during the Napoleonic Wars, being thrown in at the deep end aboard HMS Polyphemus at the Battle of Copenhagen when he was only fifteen, before being taken on as a midshipman with Matthew Flinders as he mapped much of the coast of Australia (or New Holland, as it was then). Young Franklin learned a lot from Flinders, who had himself learned a great deal from Captain Cook. Before he was twenty, Franklin had gained further battle experience as a signals officer on HMS Bellerophon at the Battle of Trafalgar. He was a lieutenant by the time he was twenty-two. When the strikingly handsome James Ross first encountered the round-faced, chubby, prematurely balding John Franklin at Lerwick in the Shetlands in May 1818, as Isabella and Trent prepared to set out for the Arctic, he must have regarded him as something of a hero. He can have had no idea that their paths would cross again in the future, or that they would be the two men to become most closely associated with the dramatic career of HMS Erebus.

Like many of the senior naval men of the time, Franklin was a well-educated polymath with a particular interest in magnetic science. This was his first Arctic commission and he took it seriously. Andrew Lambert, his biographer, assesses his state of mind at the time: ‘He might not have a university pedigree, or the status of a Fellow of The Royal Society, but he had been round the world, made observations and fought the king’s enemies. He was somebody, and if this venture paid off he could expect to be promoted.’ Unfortunately, the voyage, which he had hoped would eventually reach the far east of Russia, never got past the storm-driven icebergs around Spitsbergen, and John Franklin was back in England within six months.

The John Ross expedition to the Northwest Passage was initially more successful. Having reached 76°N and safely crossed Baffin Bay, Isabella and her companion Alexander found themselves at the head of an inlet on the north-western side of the bay. This was the mouth of Lancaster Sound, later to become known as the entrance to the Northwest Passage. But it was also the place where Ross made a serious error that was to prove a lasting blot on his reputation. When looking west down the inlet, he came to the conclusion that there was no way through, because there appeared to be high mountains ahead. In fact they were thick clouds. So convinced was he, however, that not only did he fail to bring his officers up on deck to confirm what he thought he’d seen (they were below, playing cards), but he even gave the imaginary range a name, Croker’s Mountains, after the First Secretary to the Admiralty. It was a bizarre episode. Ross, on his own initiative, then ordered the ship to turn and head for home, though not without adding insult to injury by naming an imaginary gulf Barrow’s Bay. When the error was revealed, Barrow was furious and never trusted John Ross again.

But the lure of the Northwest Passage remained strong and Barrow’s largesse next fell upon William Edward Parry, captain of the Ross expedition’s second ship, Alexander, who was duly invited to lead a fresh attempt. At thirty, Edward Parry, as he was usually known, was of a younger intake than John Ross or John Franklin, though he had been with the Navy for more than half his life, having joined when he was thirteen. James Clark Ross was once again engaged as midshipman. One of his fellow officers on the Alexander was a well-regarded Northern Irishman, Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier. He and James Ross were to become lifelong friends and, like Ross, Francis Crozier would go on to play a major role in the destiny of Erebus and that of her sister ship, Terror.

Parry’s expedition took two ships, Hecla and Griper, on what proved to be one of the most fruitful of all Arctic voyages. Not only did they pass through Lancaster Sound, removing Croker’s Mountains from the map, but they also penetrated deep into the Northwest Passage. They took the unprecedented step of overwintering on a bleak and previously unknown island far to the west, which they named, after their sponsor, Melville Island. Fortunately, they were well prepared. Each man was issued with a wolfskin blanket at night and great care was taken with the supplies, which included Burkitt’s essence of malt and hops, and lemon juice, vinegar, sauerkraut and pickles to stave off scurvy. By the time Parry and his ships arrived back in the Thames estuary in November 1820, they had penetrated hundreds of miles of previously unknown land.

Meanwhile John Franklin, despite his underwhelming achievement on the North Pole expedition, had been offered another chance by Barrow. Along with George Back and Dr John Richardson, he was given command of a land expedition to map the north-flowing Coppermine River to its mouth in the Arctic Sea. It was wild and difficult country, and as Franklin’s working life had so far been spent at sea, he was not perhaps the ideal man for such demanding terrestrial exploration. Moreover he was encumbered by the heavy equipment that was needed to fulfil the scientific obligations of the mission.

In the event, much new land was mapped, along the river’s course and along the Arctic coast, but Franklin left his return too late and his men were caught in vicious weather conditions as winter approached. Their food ran out and they were reduced to eating berries and lichens wherever they could find them. Franklin recalled later that one day ‘the whole party ate the remains of their old shoes [moccasins of untanned leather] to strengthen their stomachs for the fatigue of the day’s journey’. The dreadful conditions produced bitter divisions. Ten of the accompanying Canadian voyageurs (fur traders who also acted as scouts and porters) died on the march home, and one of those who survived, Michel Terohaute, was believed to have done so by cannibalism. He then shot an English member of the expedition, Midshipman Robert Hood, before being shot in turn by Dr John Richardson, second-in-command of the party.

The disorganised chaos at the end of the expedition was seen by some at the time as the result of Franklin’s obstinacy and unwillingness to listen to the voyageurs or the local Inuit. More recently, the editor of a 1995 edition of Franklin’s journals summed him up as ‘a solid representative of imperial culture, not only in its many positive aspects, but in its less generous dimensions as well’. But when he arrived back home a year later and told his side of their fight for survival, his book became a bestseller and, far from being criticised for jeopardising himself and his men, John Franklin quickly became a popular hero: The Man Who Ate His Boots.

Barrow’s multi-pronged attack on the Northwest Passage had brought results and, even when unsuccessful, had so firmly gripped the public imagination that men like Parry and Franklin and James Clark Ross were becoming shining lights in a new firmament – a world in which heroes fought the elements, not the enemy.

In 1824, as Erebus was being carved into shape in a quiet corner of south-west Wales, two of her fellow bomb ships, Hecla and Fury, were once more to go into action against the ice. Impressed by their sturdy design and reinforced hulls, Edward Parry, the explorer of the moment, chose them to spearhead yet another assault on the Northwest Passage.

This new journey represented a step up for the young James Clark Ross, he of the tall, straight back and leonine thatch of thick dark hair, for he was appointed Second Lieutenant on the Fury. But the expedition itself was not a success. First, the ships were held up by thick ice in Baffin Bay. They attempted to warp themselves through by driving anchors into the ice and pulling themselves along using the ships’ hawsers, but it was a dangerous technique, which, as Parry himself admitted, could go quite violently wrong: on one occasion, he recorded, ‘three of Hecla’s seamen were knocked down as instantaneously as if by a gunshot, by the sudden flying out of an anchor’. Then Fury was driven ashore and had to be abandoned on the coast of Somerset Land. After just one winter, the decision was taken to return home.

Barrow, however, remained convinced that Parry could do no wrong. With the strong support of Sir Humphry Davy of the Royal Society, he therefore entrusted him with an attempt on the North Pole. The other man of the moment, James Clark Ross, was appointed as Parry’s second-in-command. Also on board were Ross’s friend Francis Crozier and a new assistant surgeon, Robert McCormick, who would go on to play an important part in Ross’s subsequent adventures.

The expedition reached Spitsbergen in June and from there the men headed off on reindeer-drawn sledges, aiming to make about 14 miles a day on their way to the Pole. They continued north, travelling by night and resting by day to avoid snow blindness. Unfortunately, the reindeer proved less than ideal for towing the sledges and were later killed and eaten; and by the end of July the party’s progress had slowed to one mile in five days. The decision was taken to turn back. A loyal toast was drunk, and the standard they had hoped to run up at the Pole was hoisted.

Even though they hadn’t achieved their goal, Parry and his men had scored a considerable achievement. They had reached a new furthest north of 82.43°, some 500 miles from the North Pole, a record that was to stand for nearly fifty years. As for Ross, he had survived forty-eight days in the ice and had shot a polar bear. Yet the fact remained that another attempt on the North Pole had failed, leading The Times to state in a prescient editorial: ‘In our opinion, the southern hemisphere presents a far more tempting field for speculation; and most heartily do we wish that an expedition were to be fitted out for that quarter.’ That, however, was to be a long time coming.

On his return in October 1827, James Ross was promoted to commander, but, with no immediate prospect of further work, was stood down on half-pay. Thanks to his uncle, however, he didn’t have to kick his heels for long. Just a few months later John Ross, who had been cold-shouldered by Barrow and most of the Admiralty after the Croker’s Mountains fiasco, won financial support for a new polar expedition from his friend Felix Booth, the gin distiller. One of the conditions Booth imposed was that Ross should involve his nephew – a condition that the bluff and curmudgeonly John swiftly agreed to, even though he hadn’t asked James first. He even promised that James would serve as his second-in-command. Fortunately for everyone, James, now in the prime of life and in need of money, accepted.

Booth agreed to invest £18,000 of his gin fortune in fitting out Victory – not the legendary flagship of Lord Nelson, but an 85-ton steam-driven paddle-steamer, previously employed on the Isle of Man–Liverpool ferry service. Ross’s idea was that because the Victory was not wholly dependent on sail power, it would be able to push its way more easily through the thicker ice. The principle was sound enough, but the crew began to have trouble with the engine the morning after they left Woolwich. Even with it working flat out, they could only make three knots. Before they had left the North Sea they discovered that the boiler system was leaking badly (one of its designers suggested they stop up the hole with a mixture of dung and potatoes). And they were still within sight of Scotland when one of the boilers burst – as did John Ross’s patience, on being told the news: ‘as if it had been predetermined that not a single atom of all this machinery should be aught but a source of vexation, obstruction and evil’. In the winter of 1829 they dumped the engine altogether, to general relief.

Despite these teething problems, they went on to have their fair share of success. John Ross, perhaps a little sheepishly, sailed Victory through the non-existent Croker’s Mountains and out the other side of Lancaster Sound. En route he mapped the west coast of a peninsula to the south, which he named Boothia Felix, shortened later to Boothia, but still the only peninsula in the world named after a brand of gin. They made contact with the local Inuit, to the benefit of both sides. One of the Inuit was particularly impressed that Ross’s carpenter was able to fashion him a wooden leg to replace one he’d lost in an encounter with a polar bear. The new leg was inscribed with the name ‘Victory’ and the date.

Their greatest achievement was still to come. On 26 May 1831, two years into what was to be a four-year expedition, James Clark Ross set off on a twenty-eight-day expedition by sledge across the Boothia Peninsula, with the intention of pinpointing the North Magnetic Pole. Just five days later, on 1 June, he successfully measured a dip of 89°90'. He was as close as it was possible to get to the Magnetic Pole. ‘It almost seemed as if we had accomplished everything we had come so far to see and do,’ John Ross later wrote; ‘as if our voyage and all its labours were at an end, and that nothing now remained for us but to return home and be happy for the rest of our days.’

The raising of the Union Flag and the annexing of the North Magnetic Pole in the name of Great Britain and King William IV should have been the prelude to a hero’s return, but the capricious Arctic weather refused to cooperate. The ice closed in and the expedition’s survival began to look increasingly precarious. As the prospect of a third winter trapped in the Arctic turned into reality, elation gave way to bitter resignation. In June, James Ross had been triumphant. Just a few months later his uncle John wrote with feeling: ‘To us, the sight of the ice was a plague, a vexation, a torment, an evil, a matter of despair.’

It was worse than anyone could have expected. Had it not been for their close contact with the local Inuit, and the adoption of a diet that was rich in oil and fats, they would surely have perished. Indeed, it was to be nearly two years before the Rosses and their companions, ‘dressed in the rags of wild beasts . . . and starved to the very bones’, were miraculously rescued by a whaling ship. This turned out to be the Isabella from Hull, the ship that John Ross had commanded fifteen years earlier. The captain of the Isabella could scarcely believe what he saw. He had assumed that uncle and nephew had both been dead for two years. So many had despaired of ever seeing them again that there was national astonishment when they sailed into Stromness in the Orkney Islands on 12 October 1833. When they arrived in London a week later, their reception was nothing less than triumphal. Their remarkable fortitude in surviving four years in the ice, their scientific achievements and their skills as explorers were all praised and celebrated. This near-disaster, far from deterring future expeditions, ensured that the Arctic would remain a potent target for the Admiralty’s ambitions and, years later, would profoundly change the course of many lives.

John Ross, now rehabilitated, was awarded a knighthood. His moment of triumph was, however, marred by an unpleasant falling-out with his nephew over who should receive credit for the discovery of the North Magnetic Pole. James claimed sole recognition, for pinpointing its position. His uncle insisted that if he had known his nephew was intending to go for the Pole, he would have accompanied him. To official eyes, it was James who was the coming man. Alongside his prickly and impulsive uncle, he appeared dependable and decisive – a safe pair of hands. At the end of 1833 he was promoted to post captain and given the task of conducting the first-ever survey into the terrestrial magnetism of the British Isles.

He had barely begun the work when word came of twelve whaling ships and 600 men trapped in the ice in the Davis Strait, between Greenland and Baffin Island. The Admiralty agreed to a rescue mission and, predictably, turned to James Clark Ross to lead it. He chose a ship called Cove, built in Whitby, and picked Francis Crozier as his First Lieutenant.

As Ross and Crozier made their way north from Hull to Stromness and into the North Atlantic, the Admiralty looked around for suitable back-up vessels, should extra effort be required. Of the two bomb ships that had been converted for Arctic travel on Parry’s expeditions, one, HMS Fury, had been dashed against the rocks on Somerset Island, and the other, Hecla, had been sold a few years earlier. That left HMS Terror, one of the Vesuvius Class, built in 1813, with plenty of active service behind her; and the as-yet-untried and untested Erebus. On 1 February 1836 a skeleton crew was despatched to Portsmouth to dust Erebus down and haul her round to Chatham to await the call. Cove, meanwhile, ran into ferociously bad weather, one gale battering her so severely that it was generally reckoned it was only James Ross’s cool, calm captaincy that saved the ship from going under. After returning to Stromness for repairs, Ross, Crozier and the Cove set out again for the Davis Strait. By the time they reached Greenland they learned that all but one of the whalers had been freed from the ice.

Despite this, the rescue efforts were seen as heroic. Francis Crozier was promoted to commander (confusingly, the rank below captain) and James Ross was offered a knighthood. Much to the dismay of his many supporters, he turned it down, apparently because he felt the title of Sir James Ross would mean that he might be mistaken for his pugnacious and recently ennobled uncle.

‘The handsomest man in the navy’ – according to Jane Griffin, the future wife of John Franklin – was, however, rather less successful in his private life. In between his many journeys, Ross had met and fallen in love with Anne Coulman, the eighteen-year-old daughter of a successful Yorkshire landowner. Ross had done the decent thing and written to her father, expressing his feelings for Anne and hoping that he might visit her at the family home. Coulman had written back indignantly, firmly shutting the door on the liaison and expressing his shock that Ross should harbour such feelings ‘for a mere schoolgirl’. His opposition was multi-pronged. ‘Your age [Ross was thirty-four] compared with my daughter’s, your profession and the very uncertain and hazardous views you have before you, all forbid our giving any countenance to the connection.’

Anne, however, was as much in love with James as he was with her. For the next few years they continued to meet secretly. Coulman’s stubborn opposition to their relationship drove Ross to write to Anne in angry frustration: ‘I could not have believed it possible that worldly emotions could have had so powerful an influence as to destroy the most endearing affections of the heart, and cause a father to treat his child with such unfeeling hardness and severity.’ Fortunately, one of James Ross’s great qualities was his determination. Once he had set his mind on something, he was not easily deflected. He continued to keep in contact with Anne, and she with him. Their perseverance was eventually rewarded.

HMS Terror was soon in action on another mission, leaving the Medway in June 1836 as the flagship of George Back’s latest ambitious expedition to extend his survey of the north-west Arctic. By September she was beset in the moving ice and was severely knocked about throughout the winter. She eventually broke free of the ice-pack and, still encased in a floe, drifted into the Hudson Strait. With her hull damaged and secured with a chain, Terror just about made it to the Irish coast, where she unceremoniously ran aground.

Before disaster struck, George Back had some kind words for Terror that could have been applied to all the bomb ships: ‘Deep and lumbered as she was, and though at every plunge the bowsprit dipped into the water, she yet pitched so easily as scarcely to strain a rope-yarn.’ His description of her in fine weather made the frog sound like a prince: ‘The royals and all the studding-sails were for the first time set, and the gallant ship in the full pride of her expanded plumage floated majestically through the rippling water.’

Erebus had no such chance to impress. Though she had come tantalisingly close to seeing some action, in the end she had merely exchanged one dockyard for another. De-rigged at Chatham and back In Ordinary again, she was becoming the ‘nearly ship’ of the British Navy.

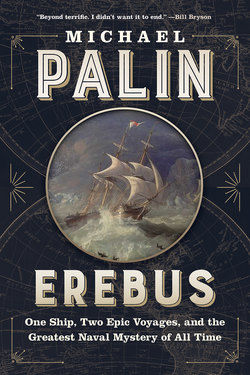

Throughout the early nineteenth century, the Antarctic remained terra incognita. James Weddell’s 1822–4 voyage in search of the South Pole – depicted here in his 1825 memoir – penetrated further south than any previous ship, but failed to sight land.