Читать книгу Erebus - Michael Palin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

HOOKER’S STOCKINGS

I’ve always been fascinated by sea stories. I discovered C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower novels when I was eleven or twelve, and scoured Sheffield city libraries for any I might have missed. For harder stuff, I moved on to The Cruel Sea by Nicholas Monsarrat – one of the most powerful books of my childhood, even though I was only allowed to read the ‘Cadet’ edition, with all the sex removed. In the 1950s there was a spate of films about the Navy and war: The Sea Shall Not Have Them, Above Us the Waves, Cockleshell Heroes. They were stories of heroism, pluck and survival against all the odds. Unless you were in the engine room, of course.

As luck would have it, much later in life I ended up spending a lot of time on ships, usually far from home, with only a BBC camera crew and one of Patrick O’Brian’s novels for company. I found myself, at different times, on an Italian cruise ship, frantically thumbing through Get By in Arabic as we approached the Egyptian coast, and in the Persian Gulf, dealing with an attack of diarrhoea on a boat whose only toilet facility was a barrel slung over the stern. I’ve been white-water rafting below the Victoria Falls, and marlin-fishing (though not catching) on the Gulf Stream – what Hemingway called ‘the great blue river’. I’ve been driven straight at a canyon wall by a jet boat in New Zealand, and have swabbed the decks of a Yugoslav freighter on the Bay of Bengal. None of this has put me off. There’s something about the contact between boat and water that I find very natural and very comforting. After all, we emerged from the sea and, as President Kennedy once said, ‘we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea . . . we are going back to whence we came’.

In 2013 I was asked to give a talk at the Athenaeum Club in London. The brief was to choose a member of the club, dead or alive, and tell their story in an hour. I chose Joseph Hooker, who ran the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew for much of the nineteenth century. I had been filming in Brazil and heard stories of how he had pursued a policy of ‘botanical imperialism’, encouraging plant-hunters to bring exotic, and commercially exploitable, specimens back to London. Hooker acquired rubber-tree seeds from the Amazon, germinated them at Kew and exported the young shoots to Britain’s Far Eastern colonies. Within two or three decades the Brazilian rubber industry was dead, and the British rubber industry was flourishing.

I didn’t get far into my research before I stumbled across an aspect of Hooker’s life that was something of a revelation. In 1839, at the unripe age of twenty-two, the bearded and bespectacled gentleman that I knew from faded Victorian photographs had been taken on as assistant surgeon and botanist on a four-year Royal Naval expedition to the Antarctic. The ship that took him to the unexplored ends of the earth was called HMS Erebus. The more I researched the journey, the more astonished I became that I had previously known so little about it. For a sailing ship to have spent eighteen months at the furthest end of the earth, to have survived the treacheries of weather and icebergs, and to have returned to tell the tale was the sort of extraordinary achievement that one would assume we would still be celebrating. It was an epic success for HMS Erebus.

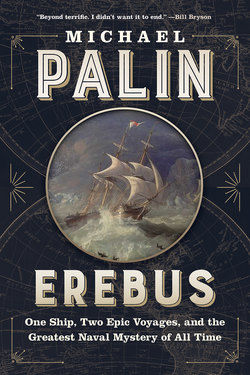

Pride, however, came before a fall. In 1846 this same ship, along with her sister ship Terror and 129 men, vanished off the face of the earth whilst trying to find a way through the Northwest Passage. It was the greatest single loss of life in the history of British polar exploration.

I wrote and delivered my talk on Hooker, but I couldn’t get the adventures of Erebus out of my mind. They were still lurking there in the summer of 2014, when I spent ten nights at the 02 Arena in Greenwich with a group of fellow geriatrics, including John Cleese, Terry Jones, Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam, but sadly not Graham Chapman, in a show called Monty Python Live – One Down Five to Go. These were extraordinary shows in front of extraordinary audiences, but after I had sold the last dead parrot and sung the last lumberjack song, I was left with a profound sense of anticlimax. How do you follow something like that? One thing was for sure: I couldn’t go over the same ground again. Whatever I did next, it would have to be something completely different.

Two weeks later, I had my answer. On the evening news on 9 September I saw an item that stopped me in my tracks. At a press conference in Ottawa, the Prime Minister of Canada announced to the world that a Canadian underwater archaeology team had discovered what they believed to be HMS Erebus, lost for almost 170 years, on the seabed somewhere in the Arctic. Her hull was virtually intact, its contents preserved by the ice. From the moment I heard that, I knew there was a story to be told. Not just a story of life and death, but a story of life, death and a sort of resurrection.

What really happened to the Erebus? What was she like? What did she achieve? How did she survive so much, only to disappear so mysteriously?

I’m not a naval historian, but I have a sense of history. I’m not a seafarer, but I’m drawn to the sea. With only the light of my own enthusiasm to guide me, I wondered where on earth I should start such an adventure. An obvious candidate was the institution that had been the prime mover of so many Arctic and Antarctic expeditions from the 1830s onwards. And one that I knew something about, having for three years been its President.

So I headed to the Royal Geographical Society in Kensington and put to the Head of Enterprises and Resources, Alasdair MacLeod, the nature of my obsession and the presumption of my task. Any leads on HMS Erebus?

He furrowed his brow and thought for a bit: ‘Erebus . . . hmm . . . Erebus?’ Then his eyes lit up. ‘Yes,’ he said triumphantly, ‘yes, of course! We’ve got Hooker’s stockings.’

Actually they had quite a bit more, but this was my first dip into the waters of maritime research, and ever since then I’ve regarded Hooker’s stockings as a kind of spiritual talisman. They were nothing special: cream-coloured, knee-length, thickly knitted and rather crusty. But over the last year, as I’ve travelled the world in the company of Erebus, and come close to overwhelming myself with books, letters, plans, drawings, photographs, maps, novels, diaries, captains’ logs and stokers’ journals and everything else about her, I thank Hooker’s stockings for setting me off on this remarkable journey.

Michael Palin

London, February 2018