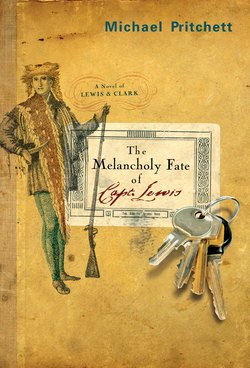

Читать книгу The Melancholy Fate of Capt. Lewis - Michael Pritchett - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6. “…a double spoken man…”

ОглавлениеOn Saturday, Bill and Emily floated the river, a relatively clear tributary that eventually met the Missouri, and was best navigated in the fall, after the July rainy season. It wound past one edge of the zoo, an open-air theater, Bill’s usual golf course, and the head of a trail he’d once gone up on a long Boy Scout hike. They were headed out into the deeper woods east of town, Emily splashing him with her oar whenever he got hypnotized by the tiny whirlpools in the current and let the canoe turn ass-end downstream.

“Wake up, Lewis!” she cried. Another couple, whom they didn’t know, a skinny guy maybe ten years older than his red-headed wife, and a second pair named Jasmine and Leslie, were also along, having signed up, like he and Emily, without knowing the others. They all laughed a lot, at anything, he noticed, while he and Emily were not quite so merry. Henry was with friends for the weekend, so they were free to act like a childless couple, cursing like sailors if they felt like it. Lewis’d come prepared for some woodsy frolicking with three Trojans zipped into his fanny pack, and some airline-sized fine whiskeys to enhance Emily’s natural proclivities. She liked it in the woods. “Like bears,” she told him. “I feel like a really hot lady bear in the woods.” For him, it went a bit beyond that. Everything worked better, his senses, bowels, hard-ons, etc. He slept more and snored less. He also felt a creeping sadness and a constant crying feeling in the back of his throat, like he would at last grieve something he hadn’t yet. His balls ached.

They floated easily through the afternoon in clear, blue-sky weather, above the leaf-caked bottom, with the shadows of alligator gar, prehistoric monsters with dagger-lined jaws, passing like torpedoes under the canoes. And the blunted hulks of paddlefish hung in deep water, cruising with mouths open a foot for microscopic prey, some going a hundred pounds or more. The air was crisp like a green apple. He watched the other man and woman, Pablo and Rita, to see what was going on with their lives that particular weekend. Bill made up a drama, that Pablo wanted a baby but Rita wasn’t sure. They sometimes struggled with their canoe, he noted, and it wandered shore to shore.

Bill was trying to write a book about the famous Lewis, but had tried before and never finished, chucking it in disgust. Emily admired the attempts, like you admire someone who’s been struck by lightning but still ventures out. As for Jasmine and Leslie, no need to fabricate. They were gay, and that was probably drama enough for anybody. Every one of them had been married before, he wagered. He and Emily had. Yet here they were again, having plunged like polar bears into those freezing, icechoked waters, like it was nothing. The other guy, Pablo, didn’t look Latino, white hair shaved to a fuzz over his scalp, tan and athletic, and heretic-skinny with bulging John Brown eyes. Rita was just Rita thus far, a pretty redhead.

They took the easy bends in the river. It was starting to gall him all over again that he’d picked Lewis as his subject. So the country was celebrating the expedition. Two hundred years! Woo-hoo! And you say the hero blew his brains out after? Hot dog! But what else could one add to that, so long after the fact?

Maybe it was just a story about a bunch of white guys setting off to oppress people of color. But many in the crew were only half white. Peter Cruzatte was half Omaha, and George Drouillard half Shawnee. Sacagawea was Shoshoni and her husband half Otoe. Or maybe Paiute, he could never remember. He’d surely get it wrong. What he’d come to believe about the expedition would screw with the facts, causing unconscious omissions, errors. They didn’t allow married men to sign on, which indicated just what they were getting into. Private Frazier, it turned out, was a fencing master, and sort of a throwback since gunpowder had made swordplay obsolete. Naturally, the one guy who died on the trip, Sergeant Floyd, signed up to rid himself of chronic health trouble. It worked! Lewis told his mom not to worry about him going, that he was just as likely to die at home. Which could be read different ways.

Whiteness was a big preoccupation. In fact, whenever they met a light-skinned Indian, it always excited them like they’d found proof of something. The ten Lost Tribes of Israel? Or was it something else? The darkest member of the party had the least power, and that was Clark’s slave, York. And Clark was treated like Lewis’s equal, but he wasn’t. He was called “Captain” by the men, but wasn’t. And Lewis promised Clark he’d fix it, but it was actually Bill Clinton, forty-second president, who finally did.

Jasmine and Leslie drifted up beside. Jasmine, in an Aussie bushmaster hat, smiled at him. “So what do you do?” she asked.

“History,” he said. “I’m a historian, of sorts. I teach high school. And this is my wife, Emily. She works with the learning-disabled and the behaviorally disordered, which is how she got me.”

“Funny. Leslie’s a PE teacher. I don’t know what I am,” Jasmine said, with a laugh. “A kept woman, I guess.”

“Bill’s writing about Lewis and Clark,” Emily said, paddle across her knees, squinting back at Jasmine.

“Oh. So I guess this is research for you,” she said. “So tell us something interesting about those guys.”

“Um, okay,” Bill said. “At the very end of the trip, Clark makes a promise to Sacagawea that he and his fiancée will take her little boy, Jean, and raise him as their own. Without consulting the fiancée, of course.”

“Whoa, that is interesting. So, in your book, you’ll say he was Clark’s bastard?” Leslie asked pleasantly, making a sun shade with her fingers, grinning at him.

“Actually, she was already pregnant when she joined them. But she had another baby right after, and the Clarks took that baby too.”

“I bet the fiancée was pissed beyond reason,” Jasmine said.

“So, a little native action on the side, huh?” Leslie said. “A little squaw action.”

“I heard all those guys died of syphilis,” Pablo said, pulling their canoe abreast with vigorous paddle strokes. “Weren’t they all dead before they were thirty-five?”

“I guess that’s somewhat true,” Bill said, “although—”

“When you get done writing about them, I’ll tell you who else would make a great buddy story,” Pablo called back to him. “Hitler and Eichmann!”

Bill shrugged, letting that go, dragging his paddle and allowing Pablo’s canoe to get ahead in the line. He mostly didn’t mind when people talked smack about the captains. Something about the subject was provoking. Even the most civil people said things they hadn’t planned to say. Ahead of them, Pablo continued loudly, “So where are the Indians on this trip, anyway? Somebody point out a Native American for me.”

“But Lewis was just a patsy, wasn’t he?” Leslie asked him, moving the canoe in behind his. “I mean, all those guys thought they were enlightened, didn’t they? And weren’t they really just Chapter Two in a final solution against nonwhiteness?”

He shrugged again, and noticed he was becoming spiritually blank, losing the ability to know his feelings. They kept paddling, though the current was taking them where it wanted and at its own speed. He never knew what to say. Not that he wanted to defend the captains but, after all the research, he felt like he knew them. It was a symptom of the depression, too, a tendency to freeze up and not be able to really reach other people, or yourself. And though they called and called to him, he made no answer, and could make no answer.

They swung around a bend, and their outfitter’s teenaged employee was there as promised, waiting to help them unload the canoes and portage them to a trailer. He’d pitched the tents, stacked the firewood, even started the fire. Two propane stoves waited on a table and the coolers full of “provisions,” on ice, rested underneath. They didn’t have to do a thing, having paid a lot not to. But still they complained about how easy it all was, and how lavish. Russ, their teenaged cook and valet, furrowed his brow at their guilty remarks but said nothing. One whole cooler was full of wine, and Russ pulled the corks and poured the icy-cold stuff into real glasses. He was starting to smile as he handed them out.

Bill rallied after his first glass, and found he was able to enter the moment again. Emotions were such tricky, roller-coastery things anyway, and his were worse than usual. For instance, he’d got fixated on Rita over the past several miles. How serious she was! And how little she smiled or talked, and how private she was with her expressions, her eyes. Rita was having a different experience of the river than the rest, it seemed. And Bill noticed. If there was an unhappy woman nearby, he always knew it. Pablo wasn’t doing anything about it, nor did he seem aware. But Bill often felt this, that other men were waiting for him to step in and help them out of these puzzling situations—so he did. He didn’t even mind, and did it with one hand tied behind his back.

As for Rita, some kind of darkness was trapped around her. She wasn’t comfortable with these strange women. She was afraid they’d figure out . . . something. He couldn’t pick it up from where he was and got closer. “Rita, how’s the wilderness treating you?” he asked, setting his pack down near her.

“Better,” she said, holding up her wine.

She sat on her duffel, casting nervous glances around at Emily, Jasmine, and Leslie as they unpacked with one hand and gulped their wine with the other. Rita sat knock-kneed, slump-shouldered, arms crossed over her breasts, like a girl at camp on the first day. A great mystery about how to be happily female was closed to her. Wasn’t everyone afraid of these strange women? Didn’t anyone realize the bad things that happened when they didn’t like you? He wished Emily would come over and talk to her, but they always used man- rather than zone-coverage when socializing. “So . . . are you writing a book or something?” she asked.

“You could say that. It’s about Lewis and Clark. Actually Lewis, mainly. But somehow Mary Shelley and Washington Irving and a whole bunch of people have gotten into it.”

She nodded, drinking. They already knew each other, somehow. She looked over at Pablo, because he was the real mystery, Bill could tell, the true other, even though she showered naked with him and ate with him and picked out dining room chairs with him. And yet this stranger seemed so familiar to her, like they’d known each other before. So what was love? You struggled so hard to know the beloved. And then some weird guy you talked to for five minutes finally got you to relax. Her brow worked on this mystery. She needed to get it worked out before she and Pablo went ahead with this baby they’d been talking about, not after. And that was Bill’s generation, all right, always figuring it out ahead of time. For his own parents, there’d been nothing to figure out.

As for the captains, they were told, basically, Pull this off, and you’ll enjoy happiness, prosperity, and honor forever after. The sky was the limit, thanks to the Revolution. In fact, Lewis was given an unlimited letter of credit, carte blanche, to finance his expedition. He took his first step westward on 30 August 1803. And almost killed a woman that same day. That Lewis, the historical Lewis, was also a soft touch with the ladies, mentioning the beautiful wives of friends met along the way, and the striking looks of Pierre Chouteau’s half-breed daughter. Practically a feminist ideal, at least for the day, Lewis noted how women were treated among each tribe, and cited the worship of male and female gods, both Manitou and Michimanitou.

When Bill got up, Rita stood and came along with him and was smiling. Emily was already well into her second glass of wine. She’d wanted to come but didn’t like being parted from Henry just now. And Lewis didn’t know what to do for her exactly, but no man was a prophet in his own country. So he came up behind her and put his arms around her shoulders and she held them, and looked out into the undulating current of the river, unctuously snaking away and away oh so endlessly. “I just know he hasn’t eaten,” she said. “Some mother. I can’t even feed my own child.”

“He’ll eat when he’s ready,” Bill said.

“He’s starving before my eyes! My little boy is hungry and where am I? Drunk, and about to eat a steak.”

“It’s got to be some girl,” he said. “Cherchez la femme.”

“Did he tell you that?” She stiffened slightly in his arms.

“No, but doesn’t it always come down to that? I mean, doesn’t it?”

She shook her head, whipping his face with her brown hair, and worked loose, pushing him away. “No, I don’t like you anymore,” she said. “Go away.”

So he watched Russ turn the meat and poke the potatoes. It got dark. Jasmine and Leslie did some kissing up against a tree.

As a young man, Lewis had surely had conquests, a few. But after the expedition, he had no luck with women. And even the deepest research into these liaisons went nowhere, and uncovered nothing. Clark was always trying to set him up, but he fended off most of it, and started calling himself a “widower with rispect to love,” whatever that meant. Nothing, post-expedition, came easily to Lewis. Not like it did for Clark with his new bride and family, a house in St. Louis, a position as superintendent of Indian affairs, and promotion to brigadier general.

They gathered around the fire with their glasses, to eat the steaks withtruffle butter that Russ doled out from a margarine tub, and roasted-rosemary potatoes, and one hell of a nice trifle for dessert: custard, bananas, strawberries, walnuts, cognac, all layered in a dark-chocolate cup you could pick up and eat. Emily ate barely half her steak, and mulled one bite of potato in her mouth, then spat it into her napkin. But nobody turned down a refill on wine. Soon her eyes were on fire from the inside, and a high basted color came into her face. She laid her head on his thigh and gazed into the fire.

“Didn’t they eat a lot of dog on the trail?” Leslie asked.

“Lewis preferred it to anything, but Clark wouldn’t touch it,” he said. “They were hungry in the winter. One time, they ate their candles. Another time, starving dogs crawled into camp and ate up their moccasins.”

“I know it’s supposed to be a proud moment, or whatever, but I find the whole thing kind of sad,” Rita said.

“I agree. Like with the buffalo and everything,” Jasmine said. “How they were all gone in just a few years.”

“No, I mean everything about it,” Rita said. “Every last thing.”

“I bet they got a lot of action on the trail,” Pablo said.

“If the captains did, somebody cut it from the accounts,” he said. “The men hooked up frequently with the native women and that was treated as no big deal. Except for this one time, when somebody’s husband caught his wife coming in late and stabbed her three times.”

“Sounds like a big deal,” Emily said.

“True,” he said. “But don’t some diplomatic practices do terrible violence to the individuals involved?”

Jasmine, who was tough, nodded matter-of-factly. Of course, women were generally tough now, in the new century, and had few illusions. The male-dominated power structure was toppling more easily than expected. Men were letting women into everything now, pulling back every curtain sort of sheepishly to reveal . . . ta-da! . . . nothing much, a box of Playboys, a few French ticklers they’d bought one time at a truck stop. Surprise. No dripping female corpses hanging from the rafters. Oh well.

Russ topped up their wine. Emily’s breathing on Lewis’s thigh was causing a slow-glowing tumescence to develop. Pablo gave Rita a back rub as she sat with her forehead on her knees, and she was groaning.

“Lewis killed himself, didn’t he?” Leslie said, with her sort of bulging eyes on his, an anxious expression. “Do I remember that or am I making it up?”

“That’s tragic,” Rita said, with eyes closed to better feel Pablo’s hands.

“Please. That’s not tragic. Tragic is wringing hands and tearing clothes,” Pablo said. “Tragic is everybody laid out dead at the end on a bloody stage.”

In the firelight, his face was almost medieval, bearded, wild-eyed and monk-like.

“Maybe tragedy isn’t that obvious now,” Bill said. “Maybe it’s quieter and it hides better.”

“A busful of kids going over a cliff,” Rita said. “That’s tragic.”

“That’s horrible,” Bill said. “It’s a catastrophe and a disaster, but is it tragedy? Does it show agency on the part of the hero?”

“It does if it’s your kid on the bus,” Emily said quietly.

“But traditionally, the hero has to choose death,” he said. “And in fidelity to something bigger than mere survival.”

“Who’s going to call up some kid’s mother and tell her her kid’s death doesn’t qualify as tragedy?” Emily asked. “Who, Bill?”

“By that logic, Bill,” Rita said, “the death of a child could never be a tragedy.”

The wine had loosened his tongue, and his voice was ringing clearly against the iron dome of the dark sky. He’d forgotten he wasn’t in class. He’d actually been trying to say something about Lewis, but doing it drunkenly. Facts rose up in his head, joining with other facts, making exciting new designs for the book or pointless ones: The French engagés were used to six meals a day, and found two meals barbaric; on the very first day, they passed a creek named for a Spaniard who’d killed himself at its mouth.

He finally answered Rita. “But it’s not me saying these things. It was Poe who said that art, in order to be art, has to be beyond such things. Amoral.”

“Dope fiend,” Jasmine said. “Sour little man.”

“I liked his one story,” Russ said, “about the heart trapped under the floor while it’s still beating.” So now the hired help, least among them, had come to Bill’s aid.

“Look, never mind,” Bill said. “I’m just a history teacher.”

“I want to read your book,” Pablo said, “even though you just gave away the freaking ending!”

Bill shrugged, smiling, with that dark and familiar feeling, of nothing being any use. What good was a thing if it made people awkwardly quiet, if it caused them to suspect you had no heart? Why open your mouth if it only caused people to more carefully watch you?

“Bill, read us something,” Emily said, “from the journals.”

His copy of the journals did happen to be on top of his pack, full of Post-Its, swollen up to twice its size. He read the entry for Lewis’s thirty-first birthday, in which he chided himself for living selfishly thus far in life and resolved to live for humanity from then on.

“Poor guy,” Jasmine said. “Nowadays, we just join the Peace Corps.”

“And at thirty-five, we come crawling back to our desk jobs, and thank God on our knees for flushing toilets,” Pablo said.

Bill held the book. The expedition truly got under way in May 1804, with three cheers from the small party on shore at St. Charles, Missouri. They soon met Daniel Boone, then turned north along with the river just west of what’d become Independence. Mormon holy land. Harry Truman’s birthplace. They just missed a detachment of Spanish troops sent up from Santa Fe to intercept them. But the really weird part was who’d sent it: one General James Wilkinson, chief of the U.S. armed forces and Spanish spy known as Agent 13. He’d later be linked to a plot by Aaron Burr, Tom’s vice president, to divide the union, seize the western U.S. and Mexico, and set himself up as emperor of a new nation called Burrania, with his daughter Theodosia by his side. And if anything about this filial tie seemed improper, then that explained the “despicable opinion” Alexander Hamilton voiced about Burr, and why Burr called Hamilton out in July 1804 and killed him.

It was all kind of crazy, how it all intersected, with Lewis in there somewhere, too, corresponding with Theo within a month of his death.

Bill read aloud from a part where Lewis went out hunting, a day he got chased by a grizzly, almost pounced on by a lynx, and charged by three buffalo, all within an hour’s time. Which rattled Lewis so, he thought it must be an enchantment or a dream. It read uncannily like Dante’s encounter with the lion, the leopard, and the starving she-wolf in The Inferno.

“Would we like this guy?” Pablo asked. “Would we invite him to pull up a stump?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “A friend of his said he was stiff, bowlegged, without grace, and that he reminded you of Napoleon.”

“Sounds like my ex,” Leslie said ruefully, blinking at the fire.

“Sounds like everybody’s ex,” Rita said.

“I’ve got more about Lewis and the Virginians, from various sources,” he said. “Washington Irving wrote a story in which he called them—let’s see here—‘a pack of lazy, louting, dram-drinking, cock-fighting, horse-racing, slave-driving, tavern-haunting, sabbath-breaking, mulatto-breeding upstarts.’”

By now, the dark had come down all the way, like a lid, and they were fully lubricated. Russ watched the fire, and them—Bill noted—in wonder edging toward alarm. His job forced him to rub up against a white-collar world that scared and disgusted him by turns, and would send him right into forestry. “I thought they were heroes,” Russ said. “I mean, that’s what I was taught.”

“How come he never married?” Rita asked. By now, she was looking fairly gorgeous in the firelight. And just why did women have to be so beautiful? Why did the desire for them not only not diminish with time but actually get worse and worse? In fact, it hurt so much, sometimes you wanted to hurt them back. Meanwhile, Emily lay on him. But was clearly thinking of Henry, her worries only blunted by the wine. And Bill didn’t know a single trick or joke or caress to snap her out of it.

“Maybe he seemed doomed,” he said. “He had his chances, but maybe he scared them all away.”

“I don’t buy that,” Jasmine said. “Doomed is sexy as hell. Doomed means you won’t hang around and get fat and boring.”

He nodded. It certainly was a mystery, not unlike the New World itself.

They passed a bluff that burned perpetually, eternally, 24–7, and stank of sulfur and brimstone. And long stretches of grass so finely manicured, you could play ninepins on them, like the little men in that Washington Irving story. Enormous flocks of white cranes flew high above. They knew so little about how the world worked, they were relieved to see storm fronts moving west to east, just as they did in Virginia. They were alive at a time when there were migrations of green and yellow parrots so vast that, flying at sixty miles an hour, it might take two full days for a flock to pass overhead.

“Tell us something shocking,” Rita said. “Something we wouldn’t know.”

“Lewis had a servant named Pernier with him when he died. That guy killed himself, too, about six months later,” Bill said. “He did it in the snow outside the White House. With laudanum.” He had to be careful now and hold himself back or he was going to fall into her eyes. But you always wanted a Rita, or a Diane, or a Laura. And you simply went on and on wanting her, and she probably didn’t exist. Probably. Even when you thought you’d found her, as soon as you married her, she ceased to be. That thing about her died.

About twenty years after the expedition, as Clark was fading, he received a visitor, America’s most elegant pen, Washington Irving, who’d fled to London, away from the terrible reviews of his books, where he gave up storytelling for history. There, he’d come very close to a fling with the widow of the poet Percy Shelley, but was scared off by something in her eyes, her gaze. He wanted to write a “Where are they now?” about the expedition, and to find out why so many were dead so young, why Lewis had killed himself, & etc.

Which brought up other strange intersections, that Irving sat at Burr’s defense table during his 1807 trial for treason as his legal counsel, and saw many noteworthies there, including General Wilkinson, Lewis, and Theodosia Burr. And in fact, Lewis and Theodosia were seen dining together in the evening, and going out riding in the afternoon. So they all kept turning up together.

Probably, Clark told Irving about the strange artillery they’d heard in the Black Hills, like a six-pounder firing at a distance of three miles. And maybe Irving remarked about Rip Van Winkle hearing just such a sound in the Catskills before meeting those grim, silent little men. Which may have reminded Clark of Spirit Mound in South Dakota, where he’d gone to see some fabled little men or devils, eighteen inches high with grotesque enormous heads, and blowguns that killed at great distances.

“What else? Anything else?” Rita asked.

“Always something else,” he said to her. “A guy named Peter shoots Lewis while they’re out hunting together and then denies repeatedly that he recognized Lewis was his target.”

“There it is,” Pablo said. “The Christ metaphor.”

Eyes looked back at Bill’s out of the dark, with Rita’s beauty in the firelight sort of stopping his heart. God or Someone seemed to love to torment mortals by placing His most ideal visions within view but not within reach.

“Now tell them the great irony,” Emily said.

“He kills himself for nothing,” Bill said. “The government bankrupted him by refusing to pay the expedition expenses. But then, three years after he was dead, they called it a simple misunderstanding and paid them.”

“But tell the thing about his assistant,” Emily said. “This’ll make you cry.”

“Oh. Naturally, when Lewis gets the job as Jefferson’s secretary, somebody else gets passed over for it,” he said. “So, when Lewis is later made governor of Louisiana, guess who his assistant is? The guy’s brother!”

Groans and laughter. “And after Lewis’s suicide, it was the assistant’s fault, everyone said, for undermining Lewis and generally making his job a living hell,” Bill said.

Pablo watched him with glittering mistrust in his possibly Cuban American or maybe Argentinian eyes. Life was about who did the best tricks for the women’s pleasure. There wasn’t anything else: if you had that, you had all the marbles.

Russ at last said his good-nights and got in his truck and drove away. Leslie watched him go and said, “I think my heart is broken.”

“I’ll make you forget him,” Jasmine said.

“Man, the values out here are strictly Kennedy-era, aren’t they?” Pablo asked. “Twenty minutes out of town and we’re back in pre-Elvis times.”

The evening was winding down, Rita sitting in Pablo’s lap, Leslie and Jasmine in the grass thigh to thigh, and Bill looking forward to eight hours of drunk, dreamless sleep. “So, anybody see a Native American around here?” Pablo asked. “What’s the story, Bill?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “They arrive in a village just after a miracle has occurred: a wildfire has burned straight over a half-breed boy and he’s survived it without even a burn. The old men of the tribe credit his half whiteness with saving him, when actually it’s his quick-thinking mom, who threw a wet buffalo hide over him. I mean, if you want reasons, that could be one.”

“I want to read your book, Bill,” Rita said, just as she and Pablo were getting up. Before he could say anything, Pablo yanked her into a tent. Emily helped him up, then pushed him into theirs.

On the sleeping bag, she wriggled out of her jeans and underwear and threw them in his face. As she leaned back on her elbows, knees together, the triangle of her pubis, Battery of Venus, as Lewis called it, was dimly visible. He reached for the fanny pack, but she stopped him and pulled him to her. “You don’t need that,” she said. Which caused his hardness to suddenly falter, to fade. “Oh, merde. I said the wrong thing again, didn’t I? That’s me, all right,” she said.

“I’m drunk is all,” he said.

“Or not drunk enough. Still reasoning. Lewis never stops reasoning,” she said, then turned over, putting her rump to him, and covered her head with the pillow. He pulled the other sleeping bag over them, over her nakedness, and touched his forehead to her back between her shoulder blades, and thought of Lewis.

As gifted as Lewis was as an explorer, he could be rash and unforgiving as the Old Testament God. When a man deserted, Lewis ordered him run to ground and shot on sight, which the men wouldn’t do, returning him to camp instead. He had a man flogged for saying mutinous things, a private whose name happened to be New-man. As plentiful as game was, they were terrified of starvation, and killed everything in sight, even hawks, ravens, eagles, and swans. They ate coyotes. Early in the journey, unbeknownst to them, the nation’s third vice president called out the first treasury secretary and shot him dead. Odd, all right, and about to get odder.

Trying to sleep next to Emily, he thought about Lewis’s grave, which was located not a hundred yards from where he’d died that night in Tennessee. For a long time, there hadn’t been a marker, just some split rails thrown there to keep the pigs out.

Where Bill was with the book, they’d just passed a creek called l’eau que pleure, or “the water which cries,” and Sergeant Floyd was about to take ill and die. And then Lewis would almost poison himself to death, tasting a mineral sample for purity. They’d pass the grave of Blackbird, a Mahar chief, known for his magical ability to cause his enemies to sicken and die. Of course, the magic was arsenic, which he’d purchased from a trader.

Trying to sleep against Emily, he ran the facts as a sedative, and thought about time, and sitting in meetings at school waiting for someone to make their point. He wanted to hurry everything, but didn’t know why, because there was no hurry, and nothing to get to but that last item on the do-list: get buried.

Before he could work it all out, he was asleep.