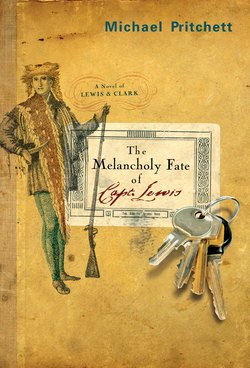

Читать книгу The Melancholy Fate of Capt. Lewis - Michael Pritchett - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

7. “…much astonished at my black servant…”

ОглавлениеOn Tuesday, after signing six kinds of waivers and releases, Bill piled his class onto a short bus. Then they rode a long way downhill, down and down into the woods, and past the zoo, heading for a specially-restored acre of glade wilderness, nature the way the captains saw it, not this confusing jumble of vines and shrubs hijacked from all over the globe. His class wandered over it, slipping on the rain-slick limestone outcrops, the girls in thin sandals with no tread and handmade ponchos.

The one he really felt for was Joaney, pregnant as a beluga, cheeks red as a pomegranate, taking mincing little steps, pausing to hunker down and gasp, glaring at him. Richard followed him close, nodding in disbelief to everything Bill said, like he made it up as he went. Which he did, sort of. And Skyler, his one Asian girl, who was crushing hard on Richard (who was pretty clearly gay), kept laughing at anything the kid said in desperate fuck-me fashion. Bill’s only black kid, T, kept sitting down, looking perplexed at the exertion. But he was a big guy, and climbing a hill was a serious matter for him: he just wanted to know why. He liked to call Bill “Doc” and didn’t turn things in on time, or format them properly. Sometimes he didn’t do the work at all.

In the book last night, Bill had dealt with such incidents as Clark’s slave York almost losing an eye from having sand thrown in it. Why it was thrown, or who threw it, wasn’t mentioned. Lewis said York sometimes frightened the tribes badly by making himself “more terrible” than they wanted him to, growling and rolling his eyes and acting like a wild animal. York told the kids he was a cannibal, saying he used to live exclusively on the flesh of children. They tried to wash the blackness off him by wetting their fingers and rubbing. When they couldn’t, they dubbed him “the Raven’s Son.”

Now, centuries later, York’s experiences in the New World were influencing T’s, and in surprising ways, including what he turned in and what he didn’t.

Lewis stood up on a rock to address the class. “Daniel Boone blazed trails through country like this,” he called out. “And at night, around the fire, he’d read aloud to everyone from Gulliver’s Travels.”

Joaney put up her hand, very cute. “Is that the one with the talking horses?” she asked. “And the giants and the Lilliputians and the Yay-hoos?”

“That’s it,” he said. They took turns standing up on the rock overlooking the Little Blue River, Skyler and her sweet china-doll looks, and pregnant Joaney, and gay Richard, and T.

“At the end of that book, Gulliver makes a terrible discovery,” Bill said. “He realizes he’s not a higher-order creature like the talking horses but the lowest of the low. He’s a Yay-hoo. And when he gets home, he sees how his wife and kids are also Yay-hoos and the sight of them sickens and disgusts him.”

“I think that happened to my dad,” T said.

“Yeah, mine, too,” Joaney said.

“Yours, mine, and ours,” Bill said. “That’s everyone’s father in that story.”

“So izzat what happened to Lewis?” Richard asked.

“Maybe,” Bill said. “After he got back, he never slept in a bed again. Couldn’t go near one.”

“He did too much drugs,” Skyler said. “Bed spins.”

“He was in some sort of trouble,” Bill said. “When you’re in trouble, you’ll shove anything in your mouth you can, even poison. Anything to get some relief.”

They all stood observing that truth from above the yellow-and-green woods, the brown, curling road and the trickly, shiny creek.

“Who died?” T asked. Did he mean, why was everyone so sad all of a sudden? Joaney looked awfully blond, and curly-headed, and had her prenatal glow, like she was being shot through a Vaselined lens. He worried he was in love with her. Or maybe with Rita, from the float trip.

“Floyd’s the only one who died,” Lewis said. “Though possibly two others during the winter of 1803. Over half were dead by 1832. Sacagawea only survived six more years, Lewis only three.”

“He poisoned himself?” Skyler said, turning Vietnamese eyes on his, her looks a legacy of French colonialism, and the twenty-year American nightmare, domino theory, & etc.

“That was earlier,” Lewis said. “He stuck some cobalt in his mouth on the trail, and it almost killed him.”

“He’s trying to do himself all the way, isn’t he?” T said. “Right? Right from the start.” He was peering toward the cataract below, and the riffles downstream.

“Maybe so. He and his horse are constantly rolling over cliffs. He’s shot at three times and hit once. A grizzly tries to eat him. In a way, even agreeing to go was suicide,” Bill said.

“He’s like some kinda circus geek,” Skyler said. “He’ll eat anything. Nothing disgusts him, not even syphilis sores.”

“What’s with the feathers?” T asked, slinging a stone, whipping it sidearm. Bill could only shrug.

“I think the whole thing is a crack-up,” Richard said. “Lewis tells the tribes the whites have possession of their country, and they totally ignore him.”

“Jefferson called the tribes his red children,” Bill said.

“Right. The great white father routine,” T said.

They moved on to the zoo, so he could show them a California condor, largest American bird. The men had shot one on the beach with a wingspan of nine and a half feet. But when they got to the cage, Bill couldn’t return the bird’s mortified, sidelong gaze; it reminded him too much of the old man’s dead eye in Poe’s “Tell-Tale Heart.”

Joaney held the small of her back, and they passed the big cats, monkey island, the sea-lion tank, and the African veldt. “They were told to expect mastodons and saber-toothed tigers,” he said. “They believed in Manifest Destiny, and Providence, and a river running east to west across the continent.”

“It’s called magical thinking,” Skyler said. “Little kids grow out of it by about fifth grade.”

They ate lunch at a corn-dog stand, and Bill wound up with Joaney at his table. No longer a child, she had to sit with the grown-ups, and was picking all the breading off her corn dog and eating only that, dipped in mustard.

“I’m gonna quit after,” she said. “Everyone says they’ll have the baby and come back, but it’s a lie. You can’t come back.”

“What’ll you do?” he asked.

“Do? What’ll I do? That’s real funny, Mr. Lewis. I won’t do anything. I’ll be somebody’s mother. I’ll live in my gramma’s old house. I’ll get some crap job.”

When he didn’t reply, she said, “I don’t need a man. I’m very independent.”

“I’m sure you are,” he said. The clouds crossed the sky rapidly now, tinged in soft circusy colors, tumbling over each other like masses of pink and blue cotton candy. Richard sat with Skyler, and had her bent over his lap like she was giving him head, while he probed her scalp and she squealed and winced.

Joaney, looking around, said, “This place is kind of crummy, isn’t it? It’s sort of had it.”

“It was nice when I was a kid,” Lewis said.

“When was that?” She laughed, winking at him. She was putting on a brave face, and he suddenly knew she wasn’t still in school for his class, but for the company. It was sort of shocking, like learning the head cheerleader has a morbid fear of crowds. He got up to see about Skyler and Richard. Richard pulled back her hair with some delight to show the swelling on her neck, a grotesque lump red as a little sun, stuck full of hairs like darts.

“Somebody do something,” Skyler said. “Can’t you see I’m diseased!”

Before Bill could say anything, Richard had taken out his pocketknife and stabbed the “ugly imposthume,” to use the nineteenth-century term. Skyler jerked, but T had come over to help hold her, pinning her arms to her thighs. The gory contents drained into Bill’s napkin. It bled some, then wept a clear serum. “Ugh. Aren’t you grossed out?” Skyler asked.

“I guess not,” he said.

Then they all got back on the bus, his class, skinny kids and tall ones, or heavyweights. Some were distraught-looking, or expressionless, clear-skinned or acne-ridden to an almost desperate state. He looked right past the healthy ones, seeing only the distressed, terrorized, and despairing. And recalled the Indian women Lewis had seen, so far gone with syphilis they’d passed into a state beyond suffering, nearly divine. The captains saw other strange sights: a couple of boulders that were in fact a pair of star-crossed lovers turned to stone by the gods, so they might always be together, their faithful dog by their side. When grieving, many of the people cut off fingers and toes, or ran arrows through their arms.

Also, in a particular lake dwelled a monstrous amphibian with horns like a cow’s—which Lewis never actually saw. Nor did he see the snake reported to gobble like a turkey, or the band of murderous little men, eighteen inches high, with blowguns and gigantic heads.

In the seat ahead, Skyler kept fingering the new hole in her head. T sat next to her, massive, immovable, refusing to cooperate until he heard a good reason why. As for Clark’s slave, York, he’d asked to be freed after the expedition, or at least to be near his wife. Clark refused at first, then tried beating him, then finally hired him out for hard labor. Though Clark at last relented, with urging from Lewis, who couldn’t bear to see a loving husband denied the comforts of marriage.

The bus now hugged the river, which looked exactly the way the captains had seen it, except for billboards, bridges, city skyline, power plants, barges, levees, dredgers, and a little airport with planes leaping off the end of the runway and banking hard right, heading west. And the river had a deep V-shaped channel now, so it couldn’t spread and wander five miles wide and three feet deep anymore. “Lo,” he said to the class, “the major artery of a teeming nation.” But it wasn’t really true; rivers hardly mattered now. And the fabled Northwest Passage, found at last by Amundsen in 1904, was utterly impractical thanks to the Panama Canal.

Lewis knew it, too, and long before they’d reached the Pacific: there was no all-water route, no great river stretching shore to dazzled shore. He noted it matter-of-factly, just the same way he wrote, “Shields killed first buffalo,” on the 3rd of August, 1804.

“So what about Sacagawea?” Joaney asked. “What’s her deal?”

“Stolen from the Shoshoni by the Hidatsa in an attack in which her family was slaughtered. Or, taken from the Hidatsa by the Shoshoni, then later stolen back. And eventually purchased by a Touissant Char-bonneau, French guide and interpreter,” he said.

“I bet they raped the crap out of her,” Skyler said. “You know they did! Why else do you take somebody?”

“Then you had to cook and clean for the asshole who stole you and raped you,” Joaney said.

“Sounds like my mother’s life,” Skyler said.

Joaney shifted her big stomach using both hands, like it was a big rock she was stuck under.

“Hey, why’d the Indians have to go and dig up Sergeant Floyd?” Richard said.

“Oh. Well, this chief wanted to put his son’s body in with Floyd’s,” he said. “That way, he’d go to the white man’s Heaven.”

“I think that’s sad as shit,” T said. “But I know black people like that.”

“Sometimes, we identify with a thing in order to handle being swallowed up by it,” he said. For some reason, he glanced down between Joaney’s parted legs, at her Battery of Venus clearly outlined by her stretch pants.

Bill thought of the falling-out with the Sioux, who tried to exact a toll from the party before allowing it to proceed upriver. And how Lewis got so furious, and called the men to arms. Fortunately, a wise chief intervened. But Lewis never forgot or forgave it, calling them the “vilest miscreants of the savage race” and telling the whole country to treat the tribe as criminals and outlaws.

Joaney suddenly groaned and sat forward, a tiny muddy puddle now down between her shoes, silvery and reflective like sperm or a snail’s track. She grabbed his hand. Skyler looked over the seat at the floor, and nodded to T, who nudged Richard. Then they just stared at poor Jo, like some hapless family band, perplexed by this event, unsure whether to make a sacrifice, dance, or pray. Bill slipped away and spoke to the driver, then came back and took Joaney’s hand.

“Tell me some things,” she said.

“Like what?” he asked.

“I dunno, but goddammit, make it quick!”

He started talking, about how they found the backbone of a “fish” forty-five feet long, just lying out in the middle of a field. And how the tribes ran gangs of buffalo over cliffs, like Jesus stampeding the herd of swine into the sea. He told about Martha F., whom Clark named a river after, and whose true identity remained a mystery, a woman lost to time. And about the meat ration, which was barely adequate at nine pounds per man per day.

He told her Lewis’s favorite dish was dog, any style. He got her to half groan about George Shannon, who kept getting lost and running out ahead of the party. Sure that he’d been left behind, he raced out so far ahead that only a chase team of hunters on fast horses could catch him. Afraid of running out of things for her, he strayed into the taboo, such as Lewis’s talk of the “Battery of Venus,” whether the women displayed or concealed it. He talked desertion and mutiny, and about Newman, who was disbarred, and the deserter, Reed, who had to run the gauntlet four times while the men bashed him with their pencil-thick brass tamping rods. “What’d the Indians. Think of that?” she gasped.

“They thought it was barbaric,” he said. “But when Lewis told them the reason, they agreed that examples were necessary, even in the best families.”

Joaney nodded, breathing fast, staring ahead. She was into something hard and reliable now, and it had nothing to do with him.

“Did he help her?” she asked. “I mean, when she needed it the most?”

“He tried,” Bill said. “Lewis was mostly into bloodlettings and strong laxatives. He got her a drink made from crushed rattlesnake tail, and possibly that helped.”

She nodded, panting. Even in extremis, he found her very lovely and dear, her skinny arms and legs, her swollen breasts and big stomach that would deflate into a pucker, her knock-knees, her lithe wrists and ankles, her long neck and dark brow, and her aloneness, and her need, and then her aloneness again. The bus gusted up into the hospital drive and he got down to help the nurse with the wheelchair, and then got back on the bus though it tore him up to leave her there. What a mystery it all was. And what an awesome race of creatures, splendid creatures, women were.

At home, he told the story to Emily and Henry at dinner. Instead of calm family time, their dinners had turned anxious, with Henry constantly stirring through his food as if for a dead mouse. Emily didn’t have too much to say about it except that Joaney ought to have had someone with her, that he should’ve at least stayed a little while, and what was the matter with people anymore, anyway?

In his office later he couldn’t work, thinking about Joaney, and about Lewis’s command of herbal cures, how he would’ve known about purple cone flower, for instance, that it was good for madness and delivered real results in rabid dogs. Lewis hadn’t done much for Sergeant Floyd, who’d died with such grace that it sounded made up. He’d calmly announced that he was “going away,” as if on vacation, and asked Lewis to write a letter for him. How romantic. So where was the crying and the pleading? Where was death’s sting? And could Lewis’s account really be trusted? The main thing Tom asked for was a daily record of the trip, and yet Lewis wrote in fits and starts, leaving poor Clark to somehow fill the gaps. Of course, certain things could be checked out, like Sacagawea giving birth during a total eclipse of the moon. It was a difficult birth, but Indian women pregnant by white men suffered more in labor, as if they’d displeased the gods.

In bed that night, Bill tossed and turned, and Emily mashed a pillow down on her head. At that moment, for all he knew, Joaney was not only in pain but all alone as well. O, what a world it was, and what a life!