Читать книгу Springtime - Michelle De Kretser - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

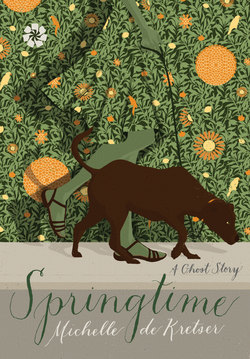

ОглавлениеFRANCES AND CHARLIE had left Melbourne so that Frances could take up a research fellowship at a university in Sydney. She was writing a book about objects in eighteenth-century French portraits. When she wasn’t at the library, she worked at home, in the sunroom. Afternoons there were so dazzling that Frances had to pull down the blinds and turn on the light. The spines of her books had already dimmed. By the end of October, she needed a fan—how would she work there in summer? The spare bedroom was reserved for Luke, who had spent three days in Sydney in September and would be returning for a week after Christmas. Charlie had left his marriage eight months after meeting Frances, and then he had left Melbourne and his young son to be with her for the rest of his life. Having more or less forgotten that she had willed these things, Frances felt their weight. Sitting at her laptop, she drew her shoulder blades together and typed: The medieval flowers, the rose and lily of the Virgin and the Annunciation, have given way to exotics: fritillaries from Persia, dahlias from Mexico. The vase is a container that draws on great distances. The boundaries of space and time that frame human life are neutralized. All the while, she was thinking of something that had happened when Luke came to stay. She had woken one night and found him standing by her side of the bed. When she opened her eyes, Luke asked, “Are you dead?”

The phone rang. Frances hadn’t wanted a landline. She had argued about it with Charlie, teasing and serious, saying, “You’re so twentieth century!” At last Charlie said he needed a landline so that his father could call. “He won’t ring a mobile.” His father had never called. When Frances answered the phone, there was a brief silence, and then a computer-generated female voice said, “Goodbye.” This happened once a week or so at unpredictable times.

There had been a string of cold nights, but the day was windy and hot. Walking down the passage, Frances passed through pools of cool air deliciously interspersed with warm gusts. In her study, she touched her faded books. She had amassed a good deal of information about jewels, furniture, dogs. For instance, she knew that whippets remained popular from the Middle Ages until the mid-nineteenth century. The only books Charlie read were large paperbacks with covers that showed backlit, hunted men, but when Frances told him about her research, he had seen the point of it at once: “What people don’t pay attention tochanges the story.” After the party where they met, Charlie gave her a lift home, and she told him about the necessity of decentering the human subject. He had parked beside a garden where three staked camellias stood as whitely upright as martyrs. It was very cold inside the car. Soon their breath shrouded the windows and the camellias disappeared. A phone rang. They paid no attention to it. However, several days later, days on which Charlie called her every afternoon, Frances said, “You could come round now. But afterwards, will you feel awful?”

“You’ll never know.” He said, “I can promise you that.”