Читать книгу Springtime - Michelle De Kretser - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

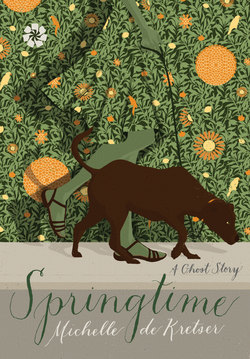

ОглавлениеTHAT SPRING, FRANCES walked along the river every morning with her dog, Rod. One of the things that had been said in Melbourne when she announced that she was moving to Sydney was, You’ll miss the parks. Other things included: There are no good bookshops there. And, What will you do for food?

Rod and Frances would cross the Wardell Road bridge and veer off onto the path that took them past the river through sports fields and parks. There were joggers and cyclists, and a girl skipping near the public barbecues. Faces grew familiar. A woman with weights attached to her wrists would say good morning, as did the Greek tailor who kept a poster of the hammer and sickle in his shop in Dulwich Hill. Frances kept an eye out for other dogs. If she saw one approaching, she swerved off the path because of Rod.

She would have said that she was heading east, but sometimes found the sun skulking behind her left shoulder. Her sense of direction, molded to Melbourne’s grid, functioned by the straight line and the square. In Sydney the streets ran everywhere like something spilled. The river curved, and the sun dodged about. On a stretch of the path where there were no trees, the sun bounced off the water to punch under the brim of Frances’s hat. It was a relief to arrive at the apartment block that could be seen on the escarpment, rising behind trees. Charlie’s colleague Joseph lived there. He had a long terrace for the view and a tucked-away second balcony no larger than an armchair: shady all through summer, in winter it floated in light. Every day, whatever the weather, Joseph sat there for ten minutes, wind-bathing without his shirt.

His apartment block, sixties brown brick with a sand-colored trim, signaled the start of Frances’s favorite section of the walk. It was shaded by she oaks, and she could look into the gardens that ran down to the path. She was still getting used to the explosive Sydney spring. It produced hip-high azaleas with blooms as big as fists. Like the shifty sun, these distortions of scale disturbed. Frances stared into a green-centered white flower, thinking, I’m not young anymore. How had that happened? She was twenty-eight.

For as long as she could remember, the weekend supplements of newspapers had informed her that her generation was narcissistic, spoiled, hyperconscious of brands. It was like reading about a different species. She was a solitary, studious girl, whose life had taken place in books; at least four years of it had passed in the eighteenth century. Her young parents had always treated her, their only child, as if she were more or less grown up. Her mother was French. Frances was taken to restaurants at an early age, expected to sit quietly and eat her food in a mannerly way while adults talked over her head. As a teenager, she devised a game in which she identified the sentence this or that person was least likely to utter. Her mother’s was: I’m not interested in what you think, tell me what you feel.

The previous year, at a party to which Frances almost didn’t go, she had met Charlie. His mother, too, was French. Charlie and Frances discovered that as children they had both called a fart a prout. Frances told her friends that Charlie had been unlucky in his women. After his parents divorced, his mother, a drunk, had gone home to live in a tower block in Nice. When her son visited her, she stole from his wallet and made him massage her feet. Now she was dead. That meant Charlie was free of her, Frances believed.