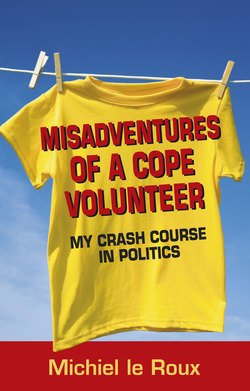

Читать книгу Misadventures of a Cope Volunteer - Michiel le Roux - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеOn 12 December 2008 the North Gauteng High Court ruled that the phrase ‘Congress of the People’ did not belong to the governing African National Congress (ANC). This ruling enabled a new political formation that had been ruffling feathers in South African politics for a few months to call itself by that name.

A month later, a further objection against the registration of the acronym ‘Cope’ by the Cape Party was dismissed by the Electoral Commission and later also the Electoral Court. Thus, after several months of being a nameless movement, the breakaway faction from the ANC finally acquired a name. The Congress of the People entered my life when it was still a nameless movement. The date was 1 November 2008 and the place the Sandton Convention Centre.

But I was a bit of a Johnny-come-lately: According to the founders of the party, the seed for the formation of a new political party had already been planted shortly after the ANC’s Polokwane conference in December 2007, where Jacob Zuma replaced Thabo Mbeki as president of the ruling party. Mbeki supporters believed that Zuma’s populist rhetoric and his blemished past rendered him unfit to lead the party, and also that his supporters’ lack of discipline was an ominous sign of what the ANC could become if Zuma was elected President. They also felt that Mbeki was treated unfairly at the conference and that the electoral process was rigged. Most of the Mbeki supporters who held prominent positions in the party were voted out and several others resigned.

Following Zuma’s victory after a carefully coordinated campaign for the leadership of the ANC, the ruling party, and ultimately the country, was expected to change significantly. As leader of the ANC it was all but certain that he would become the next South African President, which his opponents feared would result in an economic leap to the left, the undermining of the country’s judiciary and the erosion of media freedom. Citing his relationship with convicted fraudster, Schabir Shaik, his polygamous lifestyle, his remarks about HIV during his rape trial in 2006, and his singing of the controversial struggle song Aweleth’ Umshini Wami (‘Bring Me My Machine Gun’), the international and most of the local media publications painted a bleak picture of the man who would become South Africa’s next President. To those who opposed his election as ANC president, Zuma’s victory was nothing short of a disaster.

Several Mbeki supporters were torn between their loyalty to the ANC and their dedication to their ousted leader. During the struggle years, the ANC became more than just a political home to many of its supporters. Some felt that loyalty to the party far outweighed personal allegiances and that, even though Polokwane’s events were troubling, no such leadership clashes could ever justify defecting from the movement.

Others, however, wanted change. To them the rift created by the leadership battle was too wide to ignore. They believed ideological differences in the party were irreconcilable.

Cope emerged in turbulent circumstances. Covert discussions about a breakaway by dissatisfied Mbeki supporters started even before the Polokwane conference. It was undercover, it was mischievous and it was brave. It is alleged that several high-ranking ANC officials, who still form part of that party’s leadership today, participated in these discussions. While discussing their future in the ANC, the leaders who would ultimately defect to Cope realised that they shared many of the concerns about the party.

The media started reporting on serious divisions in the ANC and soon there was widespread speculation about a breakaway. With disenchanted ANC members across the country throwing their weight behind the new initiative even before it existed, the movement gained incredible, some would even say uncontrollable, momentum.

Then, in September 2008, Mbeki was forced to resign as national President. During the months following the Polokwane conference, Mbeki was in the awkward position of being the head of state without leading the ruling party. To make matters worse, the leadership structures of the ruling party were purged of his supporters and filled with people waiting for an opportunity to remove him from power. A high court ruling implying his involvement in a political conspiracy against Jacob Zuma provided such an opportunity.

While serving as Deputy President in Mbeki’s cabinet, Zuma became embroiled in a corruption saga involving the controversial arms deal. In 2005 his financial advisor, Schabir Shaik, was convicted of corruption by Judge Hilary Squires, who laid bare the generally corrupt relationship that existed between Zuma and Shaik. Following the judgement, Mbeki fired his deputy and replaced him with Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, a Mbeki loyalist.

In the aftermath of the Shaik trial, Zuma was himself charged with corruption but proceedings were delayed repeatedly while critical evidence eluded the prosecuting team. The case was drawn out over several years and procedural details, instead of the 783 allegations of corruption, seemed to become the main focus of the trial. On 12 September 2008 Judge Chris Nicholson ruled that Zuma would not be prosecuted since the allegations had been invalidated on procedural grounds. Nicholson handed down a damning judgement implicating Mbeki in a political conspiracy to thwart Zuma’s presidential ambitions.

Following a long meeting of the ANC’s National Executive Committee, the party decided to recall Mbeki after he and his cabinet indicated that they would apply for leave to appeal against Nicholson’s judgement. He was replaced by ANC Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe. The next day Mbeki formally announced his resignation. In a letter to Zuma, which was later leaked to the media, he said the following:

‘When we last met, on September 19, 2008, at the Denel buildings adjacent to the Oliver Tambo International Airport, I restated to you the incontrovertible fact that you knew that our engagement in the struggle for the liberation of our people had never been informed by a striving for personal power, status or benefit.

In this context I told you that should the ANC NEC, which was meeting from that day, decide that I should no longer serve as President of the Republic, having been the ANC presidential candidate presented to the Second and Third democratic parliament in 2004, I would respect this decision and therefore resign.’ (PoliticsWeb.co.za, 31 October 2008)

Four months later the ruling by Judge Nicholson, which resulted in Mbeki’s recall, was overturned by the Supreme Court of Appeal. Mbeki’s recall, however, was not. He became a political discard, and hardly made any public appearances after his spectacular fall from grace.

Throughout the entire ordeal that saw Mbeki removed from power, first as ANC president and later as national President, several high-ranking ANC officials publicly expressed their disapproval. Prominently amongst them were Mosiuoa ‘Terror’ Lekota and Mbhazima ‘Sam’ Shilowa. Lekota served as Minister of Defence in Mbeki’s cabinet for nearly a decade, and was ANC chairman before being voted out at Polokwane. Shilowa was premier of Gauteng Province. Following Mbeki’s recall, Lekota was the first of eleven ministers who resigned in protest, and Shilowa also stepped down from his position as Gauteng premier.

In the same week Lekota, who had been openly critical of Zuma, wrote an open letter to the ANC bemoaning what he described as ‘excesses and arrogance’ prevalent in the ruling party. He referred specifically to the call for a political solution to Zuma’s legal troubles and the accompanying threats by his zealous supporters to ‘kill for Zuma’. His decision to address the issues in public, rather than attempting to resolve them internally first, angered many within the ANC. NEC member Jeff Radebe issued a snide reply, accusing Lekota of having been an abusive chairperson of the NEC, of having reduced this decision-making body to an ‘animal farm’, and of insulting former President Nelson Mandela.

Later on, Lekota would often recall how surprised he was by the abuse piled on him following this incident, and by the wholesale failure of the ANC to respond to any of the issues he had raised. Instead, he recalls, he was told by ANC members that he was a spoilt child whose head is too big and whose ears are too long. ‘The ANC has called us dogs; the president (referring to Zuma) has called us snakes,’ said Lekota in a later interview[1] . ‘We are being branded as the “black DA”.’

A statement to Al Jazeera newsagency by an ANC Youth League (ANCYL) spokesperson that Cope’s leaders were ‘cockroaches’ who must be killed, evoked protest in the media, since it recalled the language used to refer to slain Tutsis during the Rwandan genocide 14 years earlier. When confronted about it afterwards the youngster defended himself, saying, ‘We’re not talking about killing human beings here, we’re talking about cockroaches. When you see a cockroach in your house, what do you do? You kill it.’

On 8 October 2008 Lekota ‘served his divorce papers’ on the ruling party. In a guarded statement he said that those who shared his concerns about the ANC should ‘join in a collective effort to defend our movement and our democracy’. No explicit mention of a new party was made, but it was widely expected that one would be formed.

The ruling party hit back by suspending Lekota and his former deputy minister Mluleki George’s ANC membership. It was made abundantly clear that similar action would be taken against any other members who dared challenge the ANC’s leadership. ‘It’s cold out there if you are out of the ANC, very cold,’ said Zuma[2]. This warning didn’t deter Shilowa from throwing in his lot with the splinter group. A few weeks after Lekota and George’s resignations he announced his intention to join them. ‘I have decided to resign my membership of the ANC with immediate effect and to lend my support to the initiative by making myself available on a full-time basis as the convenor and volunteer-in-chief, together with comrade Mosiuoa and others,’ he announced.

Less than six months before the country was due to go to the polls, the writing was on the wall for a split in the ruling party. Crucially, no one knew how deep the split would run. Would the ANC be able to mend the divisions? Would the ruling party keep the core of its support? Or did Lekota and Shilowa have more supporters who were ready to jump ship before the elections?

It was the most exciting political development since Mandela’s release, and from the first moment it was followed with eager anticipation.