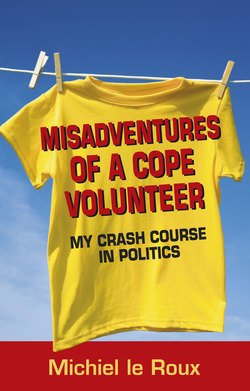

Читать книгу Misadventures of a Cope Volunteer - Michiel le Roux - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 First contact

ОглавлениеIn October 2008 I was in a steady job with a local investment bank in Johannesburg. My days comprised of meetings, emails and PowerPoint presentations. I’d wake up at 6.30am, tolerate half an hour of traffic, a day of office work, and some exercise in the afternoon if I was lucky enough to escape before dark. I shaved, wore suits, owned a Blackberry and had some cash to spend. I worked hard, impressed my clients, and got along well with my colleagues. The routine was settled and easy. But something was amiss.

Problem was I didn’t really know what I wanted. I got increasingly interested in politics, but didn’t consider it as a career. Despite suspecting that I would enjoy being politically active, I was not inspired to get involved, even on an informal basis. From a distance, the ANC seemed to be reserved for comrades only, while the DA appeared to be made up of a bunch of ex-high school debating team captains. Hence, when the prospect of a political realignment surfaced, it both intrigued and excited me.

During my time as a banker I had become a regular attendee of Wits University’s Public Conversations, which were colourfully chaired by the charismatic academic and political commentator Xolela Mangcu. I enjoyed these forums, partly because of the fascinating topics discussed and partly because the discussions satisfied my desire to be more politically active. One day in late October, after Mosiuoa Lekota wrote his open letter to the ANC Secretary General, and when the formation of a breakaway movement from the ANC seemed a certainty, Mbhazima Shilowa was invited to address the forum. I made sure not to miss it.

I arrived a little late and was further delayed by the tight security. What for? I wondered. The lecture hall was packed and I was forced to take up a front row seat. Though I did not realise it at the time, I happened to be sitting next to Wendy Luhabe, the Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg and Shilowa’s wife. I was there to see Shilowa, despite not even knowing what he looked like! Yet, he was immediately recognisable when he entered the room. He had a sense of purpose about him, and the glow that celebrities seem to acquire from spending so much time in the spotlight.

His speech was a little guarded for my liking. He spoke about the need for a direct elective system to improve accountability. He avoided levelling direct accusations at the ruling party, apart from saying that the ANC was a voluntary organisation and that members who chose to resign should be allowed to do so without being harassed. He explored the differences between a liberation movement and a developmental state, implying that the ANC’s struggle mentality had become outdated. The issue which everyone wanted to hear more about received only fleeting attention. Almost as an afterthought, Shilowa mentioned that a new political party would certainly be formed. He went on to invite us to what he called a convention of South Africans where, he said, this topic would be explored further.

Throughout Shilowa’s address a cluster of youngsters, clearly from the ANC Youth League, attempted to disrupt the speaker. This gave rise to a rather awkward situation, especially given the modest size of the gathering (about 50 or 60 people). After each statement by Shilowa one of the main agitators would shout something that I couldn’t understand, but which was clearly a ‘yeah right’ or ‘in your dreams’-type comment. Then all the others would bounce in their chairs, cover their faces and giggle. It was juvenile to the point of being pathetic. At some point the chairman interrupted proceedings in an effort to stop them, but to no avail.

Question time was even more painful. The first question contained the words ‘former comrade’ no less than fifteen times, and with each mention of the phrase the entire gaggle of youth leaguers repeated the bounce-and-giggle routine. Their ‘questions’ hardly qualified as such; they were not of the type to which one would normally affix a question mark. The majority of people in the audience sympathised with Shilowa, however, and found the young protesters’ behaviour deplorable. Despite the shenanigans I got home that evening feeling inspired. I itched to be part of the new movement.

Perhaps because I always regretted missing the excitement of the early 1990s, having been too young to really appreciate what was happening, I have been looking for a repeat of the miracle. All I can remember of politics in the transition years is how my friends’ parents stocked up on canned food and paraffin, and how bored I was waiting in the queue when my parents took me along to the polling station to cast their vote in 1994. They voted in Jamestown, a small town on the outskirts of Stellenbosch, which, under the old regime, was designated a ‘coloured’ area. Obliviously ignorant of the magnitude of the event I sadly missed out on the elation that accompanied the experience for so many South Africans.

To be born and brought up in Stellenbosch in the eighties, as I was, didn’t make for the most racially diverse childhood. I can recall thinking how brave the first, and at that stage the only, coloured pupil in my historically white primary school was. In standard five I had to break up a fight between a white pupil and a coloured pupil, the former allegedly having called the latter a ‘hotnot’. The fact that it was the first time I’d heard that word, and that I found it more amusing than offensive, testifies to my childish naivety.

I grew up with little exposure to the ugly aspects of society. I cycled to school, played in the neighbourhood streets, went to Voortrekkers and Sunday school, and was given enough pocket money to buy sweets and go to the movies when I wanted to. I had a couple of bicycles stolen and our house was robbed a few times, but I never heard of anyone who was hijacked, held up, raped or murdered. I was raised in an open-minded household and my parents taught me to challenge stereotypes. I was only confronted with racism when my friends, who were all white, made racist jokes.

During high school, with the country changing around me, I started paying more attention to current affairs. I joined the school debating team and developed some of my own opinions, but still knew more about WP rugby than about the cabinet. I got along with the coloured pupils in my class, but never thought about inviting them over for weekends. I played a game of rugby with the farm workers on my friend’s wine farm once, but ran away laughing when the supporters started breaking bottles. I didn’t spend much time thinking about either race or politics.

I only became genuinely interested in these topics after returning from Melbourne, Australia, where I spent three years at university directly after high school, doing a degree in finance. When Australians asked me about the political situation in my home country, as they often did, I tended to paint a rosy picture. I dismissed racial tensions and ascribed the country’s problems to the economic disparities. White Australians are as racist as white South Africans, if not more, I used to argue. South Africa’s race problems are just more widely publicised.

Only upon my return home did I realise the discrepancy between that picture and reality, and start fretting about it. Far from being the reconciled people I described, South Africans from different race groups seemed permanently at odds with one another. Racial tension was everywhere: in public debates, in the media, in education, in business, in sport, you name it. Where most of my peers in Melbourne were colour blind, or at least pretended to be at risk of being vilified, the Stellenbosch students were often openly racist. It was an unpleasant eye-opener and a shock.

A year later I was in limbo before I planned to head abroad again and so decided to dedicate a few months to NGO work. This opened up a world to which I was previously oblivious, and which I was intrigued by. I held two jobs: one with TSiBA Education, a free university offering business degrees, and another with Impumelelo Innovations Award Trust, which rewards public sector projects based on their innovations. The latter required me to appraise government projects and recommend the good ones for the awards. My job was to do write-ups about previous winners and drive around looking for new ones.

The first project I evaluated was the Sexual Abuse Victim Empowerment, or SAVE. SAVE is situated in Observatory, Cape Town, and assists the state prosecutor in cases of sexual abuse involving intellectually disabled victims. Dealing with persons with an intellectual disability can be complicated, and their abuse cases used to go unheard because the prosecutor didn’t know how to approach them. Since SAVE was started, the number of these cases that reached the courts each year increased from two or three, to over a hundred. Furthermore, the conviction rate increased dramatically.

Further searches for innovative projects led me to the North West province, a region I had only driven through once or twice on my way to some holiday destination. I encountered a wide variety of projects, some of which were moderately successful while others failed spectacularly. The most inspirational was the Animal Feed & Medical Distributors Co-op (AFMD) in Mafikeng. Project manager Joseph Sebolecwe told me how he came up with the idea of supplying animal feed and medicine to subsistence farmers in the rural areas when he was a young and unemployed graduate. He approached the Department of Agriculture and received seed capital for the business. Three years later, AFMD had a wide client base over an area stretching a hundred kilometres in each direction and was growing into a sustainable business.

Another inspirational project was the Ikageleng Tshwaraganang ka Diatla Project in the Mokutu township outside Zeerust. The project was run by Florence Modisane, who used to be a local social worker. In 1999 she brought together a group of women from the community to fight the problem of drug-resistant tuberculosis. It started as a nursing group doing home-based care, but with the help of government funding, Ikageleng grew into a neat medical centre with 32 nurses, two food gardens, a soup kitchen, a crèche and even a laundry service. However, Ikageleng faced a reduction in government funding, and the results were visible with infrastructure falling apart. This was a problem for all these projects: once the government stopped paying, things deteriorated rapidly.

I also came across some terrible money wasting. A poultry and vegetable project in the rural Tlhatlagandyane Village, where I had to meet the tribal leader before being allowed in the village, bought a brand new tractor that no one knew how to drive, a computer without power and an abattoir with nothing to slaughter. Yet, the water pump was broken and the dam leaked. A medical care project in Lomanyaneny Village filled an entire hall with fancy hospital beds, even though consultations were always conducted at the patients’ homes. In both cases, the government agency responsible for the funding determined how the money should be spent without consulting the project managers. Project managers complained that they had to use up their budgets, even on useless things, otherwise the budgets would be cut the following year.

The projects had two things in common: heavy reliance on government funding and a dire lack of skills. There were no mentorship programmes to assist any of the project leaders – they all had to figure things out for themselves and learn from their mistakes. The consequences were most visible at Nkagisang, a land reform project outside Klerksdorp. On what was once a thriving farm, judging by the remnants of infrastructure, I found a few dozen discouraged beneficiaries sitting around with nothing to do. They complained that the government gave them the farm and then disappeared. They didn’t know what to plant where, how to manage livestock, where to sell their produce or how to maintain their equipment. All the machinery on the farm was totally dilapidated, the animals dead and the soil barren. The instigator of the land reform reportedly took a job in town and never visited again.

Impumelelo also organised conferences on service delivery issues, such as housing, water provision and job creation. At these conferences public servants were encouraged to share their ideas and learn from each others’ successes. My role was to arrange the facilities and click the mouse to change slides while speakers were presenting. Looking out over the audience, my impression was that attendees were usually more interested in the fancy accommodation (such as the Radisson Hotel in Cape Town) than in the discussions. Session attendance was usually poor, especially early in the morning and late in the afternoon. Yet the mints and writing pads on the tables would be gone by the end of the day. It seemed as if nothing came from our efforts, except for a pile of outstanding room service expenses which I was left to follow up, usually without success.

In stark contrast to the lethargy and apathy I encountered at government projects, great things seemed to happen at TSiBA, where I volunteered as a lecturer and tutor. TSiBA, an acronym for the Tertiary School in Business Administration, is a private initiative founded by four go-getters with a shared passion for education and a mission to improve lives. The institution was only a year old when I joined, but had already achieved amazing things. The students were confident, articulate and clued-up, the facilities were fancy and the staff motivated. The curriculum reached beyond conventional academic subjects and was tailored to address the issues specific to TSiBA’s students: ‘scaffolding’ subjects like professional communication, career planning and life skills were compulsory. The directors knew about every student’s problems and made great efforts to resolve them.

TSiBA wasn’t perfect. Several students dropped out, unable to cope academically or under pressure from their families to start earning money. Nonetheless, TSiBA improved more lives than 90% of the government projects I dealt with that year. The only fundamental difference between TSiBA and the government projects, as far as I could tell, was the instigators’ bloody-minded commitment to empowerment.

My contrasting experiences through Impumelelo and TSiBA left me sceptical about the ability of our government to effect real change. Though there were some amazing people in government doing wonderful jobs, there weren’t enough of them. Many state officials did not seem to have the desire to spend government money effectively and achieve the type of sustainable development that would lift people out of poverty. Without the right people our government’s development state model was destined to fail. This was a concerning realisation for someone who always assumed that, in the new South Africa, poor people’s lives were improving every day. The insight stuck with me, and no doubt contributed to a growing desire to become involved in the world of politics.

To appreciate the impact that the formation of Cope had on the South African political landscape and to understand why there was such hype around the party, one has to understand something of the political evolution of post-apartheid South Africa. The significance of the decision by a few ANC leaders to jump ship and to form a rival movement should not be underestimated. It’s only properly assessed in the light of the history of the liberation movement, post-1994 political rivalry, the ANC’s awkward attempt to accommodate all political creeds from centre-right to far left, the personalisation of politics, and, perhaps most importantly, in view of the great face-off between Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma.

The formation of Cope represented a great deal more than a mere political defection. To many, some of whom would never even consider voting for this new party, it represented a promise of change: a realisation that ‘things don’t have to go on like this forever’. Particularly to those who felt marginalised under ANC rule, Cope suddenly presented the possibility of an alternative.

For a number of ANC members, the birth of Cope was a vindication of growing unease about the direction in which their party was heading. For an even larger number of disempowered non-ANCs, it presented an opportunity to find a political home. And for a few politically discarded old-timers, it was a chance for a last hurrah in their fight against the ANC.

It was also relevant in the context of post-colonial African politics, which is traditionally seen as being plagued by one-party dominance, tribal rivalries and personal fiefdoms. It was an act of defiance against those who claim that blind loyalty to the liberation party is somehow an inherently African characteristic. Finally, and quite coincidentally, it saw Africa’s youngest political party challenge the continent’s oldest liberation movement at the poll.

Developments on the international scene also played a role in putting Cope in the spotlight. While the disaffected leaders who would later form Cope were holding secret meetings in smoky boardrooms to discuss their uncertain future, Barack Obama, on the other side of the globe, was pulling off one of the most incredible election victories in American history. His campaign demonstrated the value of grassroot support (on which Cope would later rely), and his enchanting oratory created a world-wide atmosphere of hope (an effect Cope would later try to emulate). Obama’s campaign was closely observed in many parts of Africa and particularly, given his heritage, in Kenya. Later in the same year, the governing party in Ghana was defeated at the polls in a historical election which was almost too close to call. When America elected a black president, suddenly anything seemed to be possible. Surely South Africans could also now vote for … well … not the ANC! Change was certainly in the air.

Hence the emergence of a splinter movement out of the ruling ANC occurred against a complicated historical backdrop at the southern tip of a continent struggling to come to grips with independence, and with an optimistic world looking anxiously on. All these factors contributed to the hype.

And there certainly was a disproportionate amount of hype around Cope. Throughout 2008 it was almost impossible to open a newspaper without reading about what was initially called the ‘Mbeki camp’, then ‘Shikota’ – the nickname for Shilowa and Lekota’s movement – and eventually Cope. In the weeks leading up to the election, I recorded between 40 and 70 newspaper articles referring to the party every single day. Cope featured in nearly every opinion column, on every radio talk show and in every news bulletin. Judging by the excitement, it was difficult not to believe that the Congress of the People was about to win the election, or at least come very close to doing so.

Cope fascinated me from the very start. That night in October 2008 when I heard Mbhazima Shilowa mention that a convention was to be held as the next step towards the formation of a new political party, I knew that I had to be there.

Checking it out on the Internet I was surprised to find that there was an application process for the convention. The application form contained a tricky question: ‘Which organisation or region do you represent?’ Mmm, well. Given that this was probably the question which would determine whether I was to be admitted into the fold or left out in the cold, I thought it wise to do better than just answer ‘none’. But how does one come to represent a region? I was certainly not distinguished enough to represent Gauteng, or even Johannesburg. Neither could I imagine who, apart from the mayor or local councillors, would qualify – not that I expected too many of them to attend. That left me with the option of representing an organisation. The only one I could think of was a youth organisation whose annual conference I had attended once. (In my defence, I did afterwards email the president of the organisation to ask for permission.)

Lo and behold, I was invited to attend. All I had to do was pick up my accreditation form and arrive at Sandton Convention Centre at 9am on the Saturday morning, to the envy of my sister who had also applied to attend but, representing ‘no one’, had been rejected. I was bubbling with excitement and for the rest of the week struggled through the intricacies of bond pricing. There were other, far bigger things on my mind.

I was such a political virgin, and it showed. Expecting registration to start on time, I arrived at a shambolic Field and Study Centre in Parkmore on the Friday evening before the convention with little patience and much puzzlement. It looked more like a bring-and-braai than a registration process. Why was the queue not moving? Why were people sleeping in buses? And why were people singing Thabo Mbeki songs when he was old news? And, most importantly, were they going to check my organisational affiliation and expose me as a hoax? I had much to learn.

Waiting in the stagnant queue with about 50 other people, I started suspecting trouble when an official-looking person emerged at half-hour intervals, shouted twenty-odd random names (usually without eliciting any response), and disappeared again. I had read earlier that 6 000 people were expected at the convention. It didn’t require complicated arithmetic to figure out that this could turn out to be a long night. Apparently I wasn’t alone in this realisation, because before long the impatient amongst us had forced our way into the little room where the action was supposed to be taking place.

The room looked as though it had been hit by a paper bomb explosion. Accreditation forms were scattered everywhere, while a few shell-shocked volunteers were desperately trying to locate people’s forms one at a time. Imagine trying to locate Sipho Nghona or Michiel le Roux’s accreditation form from amongst 6 000 randomly scattered forms. The process would have taken not hours but days. The situation called for intervention.

Along with my fellow intruders, I started organising the registration packs alphabetically. Before long, we found ourselves carrying tables around and helping to look for names. With darkness falling and little light around, I was able to make myself useful, thanks to the little key ring torch I always carry. Eventually we managed to set up alphabetically arranged collection points. Logic had prevailed, and the queue was finally moving.

I was so caught up in the organisation that I forgot about the reason for my being there in the first place. When I stumbled upon my own accreditation form, it took a while for the realisation to sink in that the purpose of my intrusion into the registration room had actually been achieved. I was tempted to stay and spend the evening in this frenetic but exhilarating disorder. But patience has a limit, so I went home to rest before the big day. I didn’t even spare a moment to reflect upon how misplaced my fears had been that my organisational representation would be questioned.

The next morning, having learnt my lesson from the night before, I arrived at the crowded Maude Street entrance to the convention centre an hour after the scheduled start, presuming myself to be only a touch late. Grave miscalculation; I was still about an hour early. Everyone appeared to be part of a group, or maybe a region. There were people whose name badges proclaimed them to be, for example, Eastern Cape representatives. How on earth did they manage that? I wondered. It all left me feeling a bit out of place.

I took the first open seat that I could find that was neither close enough to the front to imply that I knew what I was doing there, nor too far into the middle of a row as to prevent my escape should that become necessary. My chosen seat landed me between a hyper-charged young man who didn’t notice me at all, and a large, endearing old lady who laughed at my pronunciation of her name.

Proceedings eventually started with a stirring rendition of the national anthem and a prayer. The convention itself was nothing short of magical. There was a real sense of occasion. In a great big hall colourfully decorated with hundreds of national flags, South Africa and its constitutional democracy was the main focus. Political celebrities took turns to bemoan the threat posed by ANC hegemony. Phrases like ‘defending our democracy’, ‘protecting the Constitution’ and ‘being equal before the law’ echoed across the packed venue. And the messages were received with the enthusiasm of a hungry mob having loaves of bread tossed at it. The seed that had been planted months earlier was growing into a sturdy little tree.

Little flags were eagerly waved about while everyone sang. And there was so much singing: beautiful, harmonious songs that seamlessly flowed into another. I was awestruck. The songs seemed to originate not from any particular group of people, but from the furniture, the walls and the floor. Every person but me seemed to know the words to every song, as well as the accompanying synchronised moves. One or two people would lead and the crowd would answer. For example, someone would sing ‘The agenda of Malema’, and then the entire crowd would answer ‘We don’t want it here!’

Multiple competing songs would be struck up at the same time, but would soon fuse into one coordinated melody that reverberated across the vast hall. I don’t know how many of the songs were stolen from the ANC, but some were clearly created on the spot, such as the song that proclaims in isiZulu: iCope le, ayina shower, iCope le, ayina mshini! (‘Here at Cope we have no showers, here at Cope we have no machine guns!’)

A Sotho one that would later become a favourite within the party, translates into: ‘I will carry the fate of Cope on my shoulders.’ Phrases like siyeza and sisendleni (‘we are coming’ and ‘we are on our way’) repeatedly echoed across the hall, again and again, louder and louder, inexhaustibly building the movement’s momentum. I wish that it was possible to portray the vivacity of the singing on paper. I did record many songs on my cell phone, but even these recordings do not do justice to the atmosphere created by the singing and the emotion it inspired. Suffice it to say that it left me with the most remarkable sense of purpose.

Thus, amidst much celebration, the conference commenced. Most of the speakers were unknown to me and I can recall very little of what was said. The crowd was so fired up that any speech that was even mildly stirring received raucous applause. The speakers merely needed to tap into the exhilaration that filled the hall on that day. None was better at this than Mosiuoa Lekota. His every word was met with applause. He spoke about the things that Cope came to represent in my mind: respect for the Constitution and a place in this country for all who live in it.

Lekota’s words set the stage for one of the many special moments which encapsulated the spirit of patriotism, non-partisanship and non-racialism that prevailed. Because it was a convention of South Africans and not a party conference, other political leaders were invited to address the crowd. When Helen Zille, leader of the Democratic Alliance, was called forward and bolted to the podium carrying a tiny national flag overhead, she received thundering applause. After her rousing speech, the crowd burst out in song: ‘Helen, Helen wethu, Helen!’ It was the politics of optimism, of reconciliation and of hope. It was intoxicating.

There were hardly any low points during the day, but with so much talk some daft statements were bound to be made. One lady called for conscription into the police service. That was awkward. Others harped on the role of communist policies in creating jobs, which didn’t sit too well with Andile Mazwai’s incredible speech about the economic climate and the role of business in politics.

At the end of a long day I left the venue with a spring in my step, determined to be part of this historical development. I timed my exit to beat the crowd, so that when they closed the convention that evening – a day early – I remained ignorant of the fact. But even returning to an empty venue the following day failed to dampen my enthusiasm. ‘They finished last night, everything was done,’ the doorman told me. ‘Eish, this Cope is going to give me many headaches,’ I replied. ‘Ja, but it will give you more smiles,’ came the doorman’s retort. We were both right.