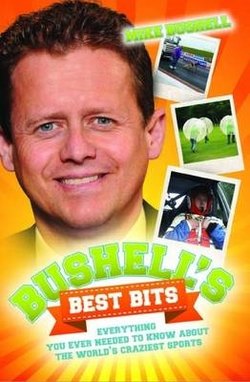

Читать книгу Bushell's Best Bits - Everything You Needed To Know About The World's Craziest Sports - Mike Bushell - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PIGEONS

ОглавлениеI end this chapter on my way to see the fastest long distance athletes of them all, those marathon travellers who are involved in one of the oldest sports, and whose place in our history is guaranteed. I am talking about the racing pigeon.

They may be the cousins of the feral mangy-looking ones that we see in towns and cities, which Ken Livingstone once described as rats with wings, but racing pigeons are very different. Many come from a long line of pedigree birds going back over 20 years. They are vaccinated against various diseases and parasites, and dine only at the top bird tables eating the finest food. You may well spot one in your garden at some point and as well as looking smarter, the racing pigeon will have a ring around one of its legs.

If you find one, you are looking at a remarkable bird – one which has made its mark on society throughout history. There is evidence that they were reporters for the ancient Olympics in Greece, flying the results out to the surrounding communities. But it’s their subsequent use in wars that really underlined their heroic status. They were used by the ancient Egyptians in the siege of Rome. A racing pigeon brought news to England of the death of Napoleon after the battle of Waterloo, and over a century later nearly half a million birds served their country in the two world wars. They were a vital part of the war effort.

They had proved so effective at getting messages back home from the trenches in the First World War that at the outbreak of World War Two, some 7,000 of Britain’s pigeon fanciers gave their birds to the military to act as carriers. The National Pigeon Service was formed and as a pigeon fancier himself, my Uncle Don was allowed to stay at home rather than being sent to fight. It was more important that he was supplying and training his pigeons. During the war, pigeon lofts were built at RAF and army bases and nearly a quarter of a million birds were used. All RAF bombers and reconnaissance aircraft carried pigeons in special waterproof baskets, and in case the plane had to ditch into the sea, a message was placed in a container on the pigeon’s leg so it could fly back and report what had happened. Many more were dropped by parachute to help the French, Dutch and Belgian resistance.

The intelligence they ferried back saved thousands of lives at a time when using a radio was far too dangerous. Pigeons themselves though carried a risk. As their reputation spread, being caught with a racing pigeon meant death by German firing squad.

It wasn’t just the British who had cottoned on to their value. The homing pigeon was also used by American, Canadian, and German forces all over the world. And their work didn’t go unrecognised. Animals that served in the war were later awarded the Dickin Medal, commonly known as the Animal Victoria Cross. Horses, dogs and a naval cat were among those to have the medal hanging around their necks, some posthumously, but of all the 53 Dickin medals handed out for animal bravery, 32 of them went to pigeons.

One bird, GI Joe, was awarded the honour for saving over 1,000 Allied soldiers in one move. On 18 October 1943, an American infantry division called for a heavy aerial attack on a town called Colvi Vecchia in Italy. It was occupied by the Germans, or so it was thought. To the Allies’ surprise, the Germans retreated from the town and a British brigade was able to secure the area that day. They would have become the victims of a friendly fire massacre, because radio signals were failing to get through to their base telling the Americans to call off the bombing. So GI Joe was released, with the lives of a whole division resting on his wings. He flew 20 miles in 20 minutes and arrived just as the American planes were on the runway. The mission was aborted.

Another pigeon, Winkie DM, helped rescuers find his stricken crew after their plane had crashed into the sea in 1942. And then there was White Vision. He flew 60 miles over stormy seas from the Hebrides off the north of Scotland, through thick mist and against a vicious headwind. Visibility was no more than a hundred yards for most of the journey and so rescuing her stricken RAF crew would have been impossible without precise information about where they were. Thanks to White Vision struggling against the odds, this crew was also saved. Even more recently, in the Gulf War pigeons were again valuable, because their messages weren’t affected by electronic jamming.

Racing pigeons were already been involved in sport long before the world wars. Long distance racing grew with the spread of the railway system and was officially organised in 1897 with the formation of the Royal Pigeon Racing Association. The spread of the railways was important, because one of the ways pigeons find their way home is by recognising landmarks or lines on the ground, be it a railway line or road. That’s not their only talent, because on their own, map reading skill wouldn’t be enough to get them back home during 1,000-mile races.

Research is still being done to pinpoint exactly what it is, but it’s thought they have an inbuilt ability to navigate using the position of the sun in the sky and the earth’s magnetic fields. Some scientific evidence which is being studied by university teams suggests they have a magnetic receptor in their brains. Other research points to them using smell.

After the war, pigeon racing became fashionable, thanks in part to footballers. In the days before they earned huge amounts of money, they would own racing pigeons rather than racehorses. They made the sport popular with the masses. Some involved in football today have maintained their love for the birds. The former England football captain Gerry Francis was one of the big names involved, and he still has a loft. At the time of writing, he is assistant to Tony Pulis at Stoke City.

What attracted the footballers was that the birds were cheap to buy, but were fast and unpredictable to race. What’s more, according to Stewart Wardrop, General Manager of the Royal Pigeon Racing Association, you just never know what may happen.

‘You can be a beginner or have a pigeon that has a pedigree you have nurtured for many generations, but everyone has an equal opportunity. No one knows if the weather is going to be right, or if the elements are going to be in your favour. You all have the chance to win the big race.’

Footballers may have moved on to horse racing, but the attraction is still the same. You can still become an owner for ten pounds, and in one race your bird could win you £20,000. You do pay a one-off fee, perhaps in the region of £100, if you want to keep your bird with a manager and trainer at a professional loft. Here it will be trained, and its natural instincts honed. Jeremy Davies is the manager of the One Loft near Malvern, where one of the big annual races is held and where 1,500 pigeons are housed. Jeremy gets birds in when they are around four weeks old. He then provides their health care and gives them the right nutrients and food to help them settle in. They learn to fly around the loft before eventually being taken for their first flight home. To begin with, Jeremy will take them a mile away. Then days later it will be two miles, and then he will release them from five miles and 10 miles, building up gradually to 50 miles. All the time, the birds are programming the map of the ground below into their brains. In races they will often track a road, even to the point of going around the outline of a roundabout in the sky.

‘It’s like managing a racehorse,’ says Jeremy. ‘You have to give them the right diet so they stay really fit and healthy. I take them out to increasing distances to train them so they get to know their way home, but it’s all about them really and their natural ability to read the earth’s magnetic fields and the sun. I make sure they have the right food, and make it nice here for them, so that they want to come home, to the hens and the cocks. These are all motivational factors to make them go that little bit faster. It’s the love of home really.’

Jeremy’s greatest reward is breeding a winning line that runs through several generations.

‘I love the creating the true pedigrees, that give birth to offspring who then also go and win races. You get to know them all, and it’s a great feeling when you see them come in from a long race.’

Not as many birds are making it back, though. 2012 was one of the hardest years on record for the sport, with 20,000 pigeons going missing. They have been hit by a triple whammy. According to Stewart, the sun’s behaviour has changed. Solar activity has increased to a level that hasn’t been seen for a thousand years. Its poles have switched for the first time in 11 years, and the resultant unseasonal weather has confused some birds.

Then there are birds of prey. Their population has been booming to such an extent that they have been moving into towns and cities where most racing pigeons are kept. Some have nested near to this free food source and even preyed on the pigeons in their own lofts. ‘It’s been an incredibly tough year,’ mourned Stewart. ‘To see 20 years of hard work disappear in a hawk attack is very upsetting, and it is driving people away from the sport.’ The main diet of a peregrine falcon is racing pigeon, while sparrow hawks will join the feast if the supply of songbirds is running out.

According to the RPRA, when a sparrow hawk attacks a flock of racing pigeons, it’s not just over for the one it choses for lunch, but the other pigeons will panic and scatter and their homing instincts are destroyed. Pigeon fanciers are bird lovers, so they insist they have nothing against the birds of prey, but they want help in protecting their sport. There used to be around 120,000 pigeon fanciers in the UK. Today there is half that number, with 45,000 association members. They are now working on ways to reduce raptor attacks. One is a £32,000 project at Lancaster University to develop ways of deterring the birds of prey. It may be in the future that pigeons carry bells or wear sequins, to make them less appealing.

The sport is now on a mission to get new people owning racing pigeons. The RPRA has started sponsoring keen youngsters to enter a pigeon in the name of their school. They want newcomers, like seven-year-old Heather Davies, Jeremy’s daughter, to get hooked. ‘I like the white ones, they’re quite pretty,’ she explained as she reached across the loft to prize her favourite from its perch. ‘I love them coming home at the end of the race and once I came fifth. My friends think it’s really cool that I am involved in the racing.’

I was invited to see the attraction too. I picked a bird called Louise who had recently won a race from France and was in top international form. I also thought it would appeal to my Breakfast colleague Louise Minchin, who would be on the sofa on the Saturday when the piece went out. I helped load the birds into a basket before they were taken to a table to be electronically recorded, ready for the race. Then it was into a car for a short journey into the picturesque Malvern Hills. I was allowed a quick pep talk with Louise through the slightly ajar lid of the basket. ‘Just turn left at the trees, keep out of the wind and head in a straight line and think of what you did to the rest on the way back from France’ were my words of wisdom, as Louise fidgeted and looked away. It didn’t seem quite the right moment for the Sir Alex Ferguson hairdryer treatment.

Then I stepped back with the other hopeful trainers and held my breath for the liberation: the moment when the birds are released. The door to the basket flipped down and for a second, nothing. Then one bird – but not Louise – stepped tentatively into the sunshine. A quick look to the right and to the left, and having given the signal that it was safe to go, the leader was followed into the sky by the whole flock. A sweeping kite of grey and white was swallowed up by the blue and within seconds they were dots above the trees, veering off to the right at incredible speed. The average speed they get up to is 60 miles per hour, but they have been recorded doing 110 mph, with the wind behind them in Australia.

In reality we would never have made it back to the loft in time to see the even the slower birds finish this five-mile race. It is a sprint for them, a race for the Usain Bolts of the pigeon world. So the birds were released for a second time, and this time, in the race that mattered, I waited the whole time at the finish. I got the call to say they were on their way. Silence descended over the loft as we anxiously watched the skies.

Within minutes of them taking off, they suddenly came into view, a flying carpet of feathers circling the trees, getting lower and lower before a group of them started to descend towards the loft. Cries of ‘come on!’ had punctured the vacuum. ‘That’s it, Louise!’ – I joined the clamour, pretending that I could tell she was in the breakaway group.

She was, as it happened, but this is where it can be interesting, and where your skills as a trainer are really tested. The pigeon has to cross the line and actually enter the loft if it’s to claim the prize. Yet Louise decided to rest on top of her home along with three others. They were sunbathing, having arrived in the leading group. This can happen, even after they’ve travelled hundreds of miles, and races can be lost and won in these few critical moments. £20,000 can be gone in an instant and so trainers like Jeremy rattle buckets and use whistle and voice commands to coax their birds over the final few inches. This is where experience counts and I didn’t have any. My calls to Louise just seemed to vex her. She eventually followed in ninth. Even though I had followed the advice and not fed her before the race, she still had no sense of urgency when it mattered.

I had seen what a lottery this sport can be, with a twist at the end that you don’t get in any other sport. Imagine Frankel stopping to eat some grass or to admire the view a couple of lengths from the winning post. Punters would be tearing their hats into pieces.

It can even happen in the biggest race in the world, the Million Dollar race in Sun City in South Africa. As the name suggests, one million dollars is given to the winner. In some parts of the world like China where the sport has really taken off, some birds have sold for hundreds of thousands of pounds. In Europe the highest price paid was €300,000. The sport has become big business and yet for a tenner, anyone of us can still get involved.

For more information of the sport and if you want to join Her Majesty the Queen and become the owner of a racing pigeon (Her Royal Highness has a loft at Sandringham) then visit the website of the RPRA at www.rpra.org

What’s more if you find a stray pigeon in the garden with a ring around its leg, it will be a racing one. It may be resting, but if it stays and looks lost, then get in touch with the RPRA via the website or via twitter on @pigeonracinguk and they can find its owner.

That’s it for this chapter on our sporting animal friends, but bigger creatures also feature later in the book when we focus on unusual sports from around the world.