Читать книгу Out of Time - Miranda Sawyer, Miranda Sawyer - Страница 7

1. Is This It?

ОглавлениеThe start is always quiet. Even when the event is catastrophic, when it’s sudden and violent and crashes in, a meteor blazing from the sky to change everything you know – even then, what people say is: ‘It happened out of the blue. Everything was normal. Nothing seemed any different. It was a complete shock.’

When what is happening is gradual, when it seeps under the door, like water or smoke, then the start is even quieter. It’s silent. You don’t notice it at all.

Middle age is a time of settled status, when your achievements, your experience and your knowledge knit together to create sustenance and prestige, and you are taken seriously, valued as a high-contributing member of society.

‘You’re a smelly bum-bum,’ says F, my daughter. Her face is full of sneer and delight. ‘And when you die, I can have all of the sweeties that are in the tin up there. And I can go to Africa to see the funny cows that Miss telled us about. And I can have your shoes that are sparkly.’

We were talking about us not having a garden, about moving flat maybe, probably not. I was feeling frustrated.

‘But, you know, feelings aren’t facts,’ said my husband, S. He had been saying this a lot to me: ‘Feelings aren’t facts.’

What you feel is not what is actually happening here.

S is an emotional man, and he uses his mantras to reassure himself as much as me. He was right. The facts remained; they were unchanging. How I felt about them – how I feel about them – makes no difference. The sun rises, the day begins, the school opens, the children go out and then they come back, I work, ideas are sent off, plans are made, the plans succeed or they don’t, meals are eaten, and off to bed, and again, and again. Time passes, more quickly than you dare to think about.

These are the facts. I am in my forties. I have a job. I am married. We have children and a flat with no garden, and a mortgage and a fridge-freezer and a navy blue estate car. None of this is a surprise. Is it?

Except … a mood can gradually take over, change the way you feel about the facts. Warp them into something different. You know how it is to fall out of love with someone? How the simple reality of them walking into a room, or the way their teeth clink on a mug as they drink their tea can make you hate everything about them, even though they are the very same person you once found so bewitching? I did not feel this about my husband. I was wondering if I felt it about myself. About my life, and who I had become.

There were other feelings. A sort of mourning. A weighing up, while feeling weighed down. A desire to escape – run away, quick! – that came on strong in the middle of the night.

But the main feeling I had came in the form of a moving picture, a repeat action. I am standing in a river, the water flowing, cold and silver, bubbling and churning around my feet. It’s lovely, really lovely, and I’m plunging my hands in, over and over, trying to catch something. Have I dropped it? Is it a ring? Or was it a fish I wanted?

No. It’s the water itself. It’s so beautiful. I want to hold it in my palms, bring it up close, clutch it to my heart. I want to stop it rushing past me so fast.

A crisis sounds so thrilling. A breakdown. A revolution. A sudden change, institutional collapse. Something dramatic.

One that happens in your forties? Hmm. Less so. We all know what that is. We see the outward gesture – the new car, the extreme haircut, the unusually positioned piercing – and we smile. We patronize. Look how silly he is, in his baseball cap, on his motorbike, with his new lover on his arm. Not dashing, not carefree, not youthful. Sad. And see her, with her tragic attempts to slow time, the clothes that are too young for her, the organic diet, the new lips. Ridiculous. Laughable.

Under the showiness of the exterior, there is a change within. All the stuff we see, no matter how clichéd: that’s just telling the world.

No show, here, however. I wasn’t running off with a Pilates expert. I didn’t blow thousands on a trip to find myself. I didn’t even get a shit tattoo. There was nothing to witness. From the outside, all remained the same. Work, kids, marriage, mortgage, blah. The facts didn’t change.

If the crisis seeps in, if the start is silent, you need a jolt to realize it. Having F was my jolt.

Our second child, she arrived late (five years after P, our son), a quarter-year before I turned 44. S and I knew we were very lucky. No matter what age you are when you have children, if they are healthy, you are lucky; and no matter what age you are when you have children, their arrival makes you feel young and old at the same time. The difference is, if you have them in your forties, the old part is more of a head-nag.

The jolt. I can pinpoint it. It happened one day when I was in the kitchen, working on my laptop. F was only a few months old. She was a good baby, cheerful and self-contained. She liked her bouncy chair and I would put it on the kitchen floor so we could smile at each other as I wrote. I typed, the washing machine spun, she bounced and grappled with a toy monkey called Monkey. All was serene. We were happy in our tiny life.

I looked at her as I wrote and I thought, You are amazing.

And then I thought, By the time you’re 18, I will be over 60.

I stopped writing.

I thought, When you’re 18, I will just about have the strength to push you out of the front door and into your adult life before I have to check into an old people’s home.

I thought, What about university fees? What if you don’t leave home completely, and want to move in again? We’ll need to sell the flat to get the money for the old people’s home.

Then I thought: If I’m tired now, that is nothing compared to how knackered I’m going to be dealing with two teenagers in my mid to late fifties. Plus, I still have all these things I need to do! Like … well, I don’t know. But things that are important for me and my development. Also, we really need to get the front gate mended.

I looked at F and she looked at me, smiling, kicking her legs. She said, ‘De du da de du,’ and twisted her hands in front of her as though she were changing channels on a 1980s TV. I thought: That’s an old-school motion right there. Then I thought: You’re showing your age.

What F made me realize was that I was over halfway through. At 40, I could still convince myself that, with a decent diet and some luck when crossing the road, I could well have more than forty years to go. It’s a lot harder to do that at 44.

I looked at F and I suddenly knew – really knew – that I had less time to go than I had already lived. That the time I had was a limited resource, that life was an astonishing gift and both were diminishing every day.

Lots of people get weird around this age, I did realize that. If you don’t get Fear of Forty, then Fear of Fifty will do it. The Fear: of everything that you have become, and everything you have not.

Eugene O’Neill, in A Long Day’s Journey Into Night, wrote: ‘None of us can help the things life has done to us. They’re done before you realize it. And once they’re done, they make you do other things until at last everything comes between you and what you’d like to be and you’ve lost your true self for ever.’

(What has life done to me? What have I done? What would I like to be?)

Victor Hugo wrote this: ‘Forty is the old age of youth; 50, the youth of old age.’

I thought about this a lot. So what happens in those ten years in between? And who wants to be a young old person? Even though that is all we ever are?

I’d had my jolt. I’d clocked my unmarked midpoint; I knew that time was running out … But what to do about it? Life is busy in your forties, whether or not you have children. It’s hard to keep everything tied down. Most days, I felt like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz when the twister hits and the house goes up, gazing out of the window as essential parts of her life whirl past. Her family, her friends, adversity (witchy Miss Gulch on the bike), livelihood (the cow – all out of control, spiralling towards the future, out of Dorothy’s reach and remit. She can’t help them, though she knows she must.

That is how my life is in middle age. So many people to take care of, so many jobs to do. A lot to catch and tether, and who can grab hold of anything when all the important bits are constantly in motion? Round and round, faster and faster. Are we moving forward or just spinning on the spot?

What I really wanted was for everything to stop, for the house to land, with me still inside. I wanted to arrive in a sunlit place, to be celebrated as a new magical queen, and to have the time to enjoy it. A place made of sweets, where the small people who surrounded me – let’s call them my children – all sang in tune and did what I told them to. Also, that when I landed, I’d crush the life out of my enemy, whoever my enemy is. That would be brilliant. Splat, gone, byeee. Gimme your shoes. And when you die, I can have your shoes that are sparkly.

Now that F is no longer a baby, she talks about death all the time. She kicks it around in her head, riffs on it to delay me putting her to bed. She doesn’t want to go to bed. Too much to do, and she’s scared of the dark (of death). She talks about death as though it’s a cool result. To her death has glamour, because it’s frightening and exotic and it won’t happen.

The idea of death. In your teenage years, your twenties, it becomes an existential concept. Actually, it can be a comfort: nothing matters, because we’re all going to die anyway. We’re all going to die, so what’s the point in learning quadratic equations, or cleaning under the bed?

When we’re young, we like to be scared by death, because it seems so remote. But in your middle years, it starts moving closer, nearer to you. Coming into focus. Becoming real.

When F was still a baby, after that moment in the kitchen, death started doing weird things in my head. It kept merging with maths. I was adding and subtracting, calculating how long I had left, how little time I had to do what I thought I had to do. Earn money. Fulfil my potential. Do whatever it was I should be doing, rather than worrying about my age and my life and what that meant.

Death maths. I was doing my death maths and I didn’t like the way the sums were adding up.

I started noticing the middle-aged men who said, ‘I’m going to live to a hundred.’ There were quite a few. The head of Condé Nast said this. A French actor. Eddie Izzard said it to me, in an interview, in a fabulously positive way.

‘I’m going to live to a hundred. Why not?’ he said, a man who ran 43 marathons in 51 days, at the age of 47, for a laugh. And then ran 27 marathons in 27 days, at the age of 54, for another giggle. Why not indeed? When Eddie said it, I was almost convinced. Maybe I, too, still had a long way to go.

But one day, when I was meant to be doing something else, I bothered to look up the stats. I saw the true death maths, and the death maths was clear. If you were born in the UK between the late 60s and late 70s, and you’re a man, then all the research says that your life expectancy is 80. If you’re a woman, it’s 83.

You can probably add on a few years if you’re middle class and don’t smoke. I thought that, too. After I’d read the research, I looked around online and found a more accurate life expectancy questionnaire. I filled it in. Carefully, I totted up my nicotine years, how much I drink, how much I exercise; I converted stones into pounds and pounds into kilograms. There were no boxes that referenced illegal drugs, or rubbish food, or terrible housing or love-life decisions. The questionnaire gave my life expectancy as … 88.

So. It doesn’t matter if you have just run the furthest you ever have in your life, or you neck kale smoothies every day, or you know some brilliant DJs. It doesn’t even matter if you yourself are a brilliant DJ, or if you are Eddie Izzard. At some point between the ages of 40 and 50, you and I will have lived more than half our lives. We have less time left than we have already lived. The seesaw has tipped. There are the facts. And these are the feelings.

It was the death maths that did for me, the pinpointing of the years left, that new (old) knowledge. It started a revving in my head, a pain behind my eyes, a loss of nerve so strong I could barely move. I’m not sure that anyone knew, though. I had dark circles round my eyes, I was tired, but so is every parent of a child under one. And, yes, I was tired because of F, but also because the panic – that dark, revving provocateur – came at night.

I would wake at the wrong time, filled with pointless energy, and start ripping up my life from the inside. Planning crazy schemes. I’d be giving F her milk at 4 a.m. and simultaneously mapping out my escape, mentally choosing the bag I’d take when I left, packing it (socks, laptop, towels of all types), imagining how long I’d last on my savings (not long, because I’d had children, so I didn’t have any savings). I’d be leaving the kids behind. Rediscovering the old me, the real one that was somewhere buried beneath the piles of muslin wipes and my failing forty-something body. I’d be living life gloriously. Remember how I was in my twenties? The travelling I did? That, again, but with wisdom …

Then I’d remember that I couldn’t leave the kids behind, because I loved them so much, and I’d start planning a different escape.

Even while I was doing it, I knew it was vital not to get involved in such thinking, that I really needed to stay put, to look forward. Certainly not hark back. If you keep staring at your past, believing your best times are done, you’ll be facing the wrong way for the next few decades. You’ll reverse into death, arse-first.

And, anyway, hadn’t I’d done those best times wrong? I would consider my younger self and shake my head. I’d decide on the turning points of my life and then spend hours bemoaning the way I’d dealt with them. What had I been thinking, refusing that job? Why did I waste so much time on that deadbeat dickhead? Why didn’t I prioritize what I really enjoyed, rather than trying to please other people? Why didn’t I push myself? What a waste! What a waster!

Sometimes, during the day, as I performed all the tiny, repetitive actions required of an adult when children are young – the wiping, the kissing, the picking up, the starting again – my mind would wander. Worse: it would assess. (No new parent wants assessment: they just want to get through.) I would assess my efforts – my life – so far, and all would come up juvenile and insubstantial. Grown-up epithets burnt in my mind, as though they were absolute truths. It would have been better to have your kids young. Buying a house with a garden is adulthood’s be-all-and-end-all. A good steady job, a good steady love life and a good steady pension are all vital for you to function in today’s world, and you should have established all of those by the time you were 30. At the latest.

In contrast, when I held up my own long-standing beliefs to the light, they seemed broken. The belief that convention was just that, conventional. That, if you and your family weren’t starving, money couldn’t make you much happier. That you were always better to go out than stay in. That a life packed full of experiences was more valuable than one packed full of possessions. I’d rushed around in my twenties and thirties because I’d wanted to enjoy myself out there, to live in the big world, rather than a small one based around acquisition. Where was the pleasure in contemplating the polished wondrousness of a wooden table, or a neatly maintained lawn?

In the middle of the night, when I wasn’t planning to run away, I found myself contemplating those pleasures with envy. We didn’t have a big table, or any outside space. We lived in a stuffed, scruffy flat.

I’d stuck with so many old prejudices – a hatred of wheelie suitcases, of drawer tidies for cutlery drawers – that I’d started to believe my prejudices were my personality. But my new-found late-night hobby of demented self-deconstruction made me see that they were not. They were merely affectations, kickbacks against my childhood and upbringing, the reactions of an overgrown teenager. An overgrown teenager with a family, a mortgage, a fridge-freezer, all that.

And part of my panic was caused by what a friend calls ‘the baby-cage stage’ – how small your world becomes when your child is small, and how manic and locked into it you are – and part of it was the fear of being over halfway through, and part of it was realizing that all the plans I had would remain unfulfilled.

Because I was middle-aged.

Still, could I be, really? There is something about middle age that is terrifically embarrassing. So embarrassing, in fact, that it cannot apply to me. Or you, either. We are of the mind to be young or old. There is cachet in both, even dignity. But not in between. Not in the middle.

Because we know middle age. It belongs to Jeremy Clarkson. It’s blouson leather jackets. Terrible jeans. Nasty out-of-date attitudes manifesting themselves in nasty out-of-date jokes. Long-winded explanations of work techniques that everyone else bypassed years ago. Micro-management of events that mean nothing – e.g. a cake sale. Useless competitiveness about useless stuff that actually boils down to an argument about status, such as Whose Child Is The Most Naturally Gifted? or How Amazing Was Your Holiday In That Villa Of Your Really Rich Mate? or Have You Seen Our New Kitchen? Christ. Who’d want any of that?

Nobody. Or at least nobody I know. I’m surrounded by people my own age who are convinced they’re not middle-aged. They know they’re not young – they sort of know they’re not young – but they’re definitely not middle-aged. And they’re boosted in this belief by mad midlife journalism. There are a lot of articles out there about how middle age doesn’t start until your fifties. Or your sixties. Or never. Everyone over 49 is shagging rampantly while shovelling in the drugs, apparently, just as they were in their twenties, thirties, forties …

Fine by me. Because that means it’s possible that they – that I – will switch easily from their youthful selves into well-maintained, sexy, eccentric, yet wise older citizens. No worries about middle age for us. Suddenly – preferably overnight, if that can be arranged – we will all transform into Helen Mirren and Terence Stamp (looking good!), with the added bonus of Bill Murray’s wit and insouciance. We will merely walk out of one room (marked Young) and into another (Old). No corridors in between, no panicked running from room to room, opening the wrong doors, searching for the exit.

Around this time, the death-maths time, I went for lunch with an old friend. In the 90s, he was a scabrous, hilarious journalist, a man who’d be sent to a far-right politics convention or a drugs den because he’d come back with something funny. Now, he was the same but different (like me, like us all). He was travelled, rather than travelling. And he, too, was struggling with midlife.

I told him of how hard I found it to combine work with little kids. He told me he would like to have children, ‘because then you know what to live for, what the whole point of everything is’.

We had a great lunch and he recommended a book to me. It was about survival. It told the tales of people who have successfully come through extreme events (successfully, meaning they didn’t die). The book was designed to inspire others to reassess their approach to life, meant to excite us boring people into living without fear.

The book was jam-packed with action. A woman was shot by her husband in front of her children. A man was attacked – part-eaten! – by a bear. Another woman had a daughter, a healthy, beautiful, 4-year-old daughter, who caught a virus and died.

God, I hated that book. But there was an image in it that stayed. I can’t remember now why it was mentioned, how it came up, but it was about a chess game. I’ll tell it as I saw it – as I see it – in my head. It’s like a recurring dream.

I am in a bar. It’s a great bar, filled with stimulating people I know a little, but not so well that they’ve heard all my best anecdotes. Someone convivial invites me to play a chess game. ‘Hell, yes!’ I shout, and sit down, slopping my caipirinha as I do so. It doesn’t matter. I am funny, good-looking and clever. Everyone in the room loves me. I am sure to win, but also, as I don’t really care about chess, I’m going to win simply by playing as I wish. No strategy, no sell-out, but many thrilling, unexpected moves that simply pop into my head. Because I’m great!

After about an hour when, in truth, I haven’t really been concentrating on what’s been going on, I go out of the room for a moment. When I come back, the atmosphere is different. The bar seems colder. All the exciting people have disappeared. The lights have dimmed; the person I’m playing chess with is hard to make out clearly.

I look down at the chessboard and see that my hot-headed, non-strategic play has meant that I have lost some vital pieces: a bishop, both rooks, a knight, several pawns. Where did they go? How could I have discarded them so unthinkingly? My armoury is diminished. Moves have taken place that I didn’t even notice, and now my position is weak.

I can see that it’s going to be tough to get anything at all out of this particular match. I’ve played it too casually. I’ve played it all wrong.

I say, with a smile: ‘Perhaps I could start again?’

And someone – my opponent, my conscience, God – answers me, in a voice that’s quiet and calm, but that fills the room, makes my ears ring, my stomach shudder: ‘No. This is the game.’

This is the game.

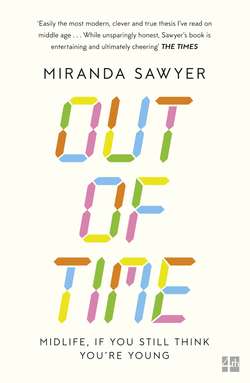

So I did the only thing I could think of that didn’t involve running away: I wrote about how I was. The fact of being over halfway through my life, and the feelings that fact created. The Observer ran the article I wrote, accompanied by a photograph of me, in a lot of make-up, looking younger than I usually do. This was very kind, though not so useful for the piece.

The article’s title was ‘Is This It?’ And it was, I suppose. Except I couldn’t seem to shake off the uncomfortable feeling, the anxiety itch.

I was still in the grips of my teeny tiny crise d’un certain age (French = more exciting), and it still didn’t show. No alarms and no surprises. I yearned for my desperation to become more flamboyant; I was like the child with stomach-ache who wants a bruise, a plaster, an ambulance rush to A&E. Nothing occurred.

It was pathetic. Who was I kidding? I didn’t pack my bag anywhere except in my head. I couldn’t leave, and a quiet crisis seems, to everyone outside it, like no crisis at all. Why couldn’t I turn my panic into flight – abandon my home, even for a few months – to have a true middle-aged catastrophe? Why didn’t I shag a builder, or a bendy yoga dullard? Why wasn’t I taking a long, solo hike across an unfamiliar landscape, pausing only to meet authentic people who would tell me the meaning of life?

I talked to S about this. I said: ‘Would you mind if I staged a midlife drama, if I left you and wandered around a bit for a couple of months?’

He said: ‘Not a bother. As long as you take the kids.’

On the radio, I heard a writer talking. There was a five-part series of his musings, inspired by the lengthy hikes he takes across cities. An imposing man, he mostly walks at night. I quite fancied this, but it’s a different prospect, going for solo rambles in the early hours when you’re a shortish woman. I thought about cycling, or going for 3 a.m. drives, but both seemed pointless – plus slowing down to talk to a pedestrian when you’re in a car at night could easily give the wrong impression. Also, I still had the days to get through, sorting the kids and earning a living; and S was going away for work, so – babysitting bills.

Still. As a result of the ‘Is This It?’ article, I got a deal from a publisher to write a book about midlife. A book. This book. And I tried to write it. God, I tried. I would bundle P to school and F to the child-minder, and then I would go to the kitchen and sit in front of my laptop, and put my coffee next to it to the right and my phone (switched to silent) to the left; and I would try to write. But the words didn’t come easy, and I had to earn a living, so I would put the book aside and go back to journalism. The quick turnaround kept me busy.

It might have been the head-mush you get when your children are small. Or denial, I suppose. But for some reason, I didn’t seem to be able to approach middle age face on. I couldn’t see it clearly. The panic was there, the Fear, the feelings. I knew how to write about them. But the fundamental crisis seemed to be happening off-camera, just out of sight, weaving itself in and around my everyday life without ever becoming distinct.

For a while, instead of writing, I talked to people. I tried to separate the personal from the more universal. Some of what I was churned up about seemed only to do with me, and some of it was timeless, a classic midlife shock and recalibration, and some of it was hooked into the time I was in, where we all were right now.

There is an element of middle age that is the same for anyone who thinks about it. Not just the death maths, but how the death maths affects your idea of yourself. Your potency and potential. Your thrusting, optimistic, silly dreams, such as they are. As they were … They’ve been forced to disappear. Suddenly, you’ve reached the age where you know you won’t ever play for your favourite football team. Or own a house with a glass box on the back. Or write a book that will change the world.

More prosaically, you can’t progress in your job: your bosses are looking to people in their twenties and thirties because younger workers don’t cost so much or – and this is the punch in the gut – they’re better at the job than you are. Maybe you would like to give up work but you can’t, because your family relies on your income, so you spend your precious, dwindling time, all the days and weeks and months of it, doing something you completely hate. Or you sink your savings into a long-nurtured idea and you watch it flounder and fail. Or your marriage turns strange. You don’t understand each other any more.

In short, you wake one day and everything is wrong. You thought you would be somewhere else, someone else. You look at your life and it’s as unfamiliar to you as the life of an eighteenth-century Ghanaian prince. It’s as though you went out one warm evening – an evening fizzing with delicious potential, so ripe and sticky-sweet you can taste it on the air – you went out on that evening for just one drink … and woke up two days later in a skip. Except you’re not in a skip, you’re in an estate car, on the way to an out-of-town shopping mall to buy a balance bike, a roof rack and some stackable storage boxes.

‘It’s all a mistake!’ you shout. ‘I shouldn’t be here! This life was meant for someone else! Someone who would like it! Someone who would know what to do!’

You see it all clearly now. You blink your eyes, look at your world, at your gut, your ugly feet in their awful shoes and think: I’ve done it all wrong.

I joined internet forums about midlife crisis where men – it was mostly men – lamented their mistakes.

‘I could have done more, been more successful, been a better person,’ said one. ‘I used to be someone but now I’m just part of the crowd.’

‘Maybe,’ said another, ‘I should just resign myself to the fact that I’m not what I used to be. But, see, this is my problem, I can’t …’

Women talked too. A friend’s Facebook status: ‘… the slow realization over the past year that I’ve messed it up. I’ve had a crap start in life and I went on to make a series of poor decisions, so now I’ve made my bed, I’ve got to lie in it. I could be so much more than a fat, grey, toothless, 44-year-old harpy living in a fucking council house with one child who despises me, another who will never live independently, and a marriage that will forever be in recovery … I know it’s up to me to change things. What’s not entirely clear is how to choose the right path. Because I don’t know where I’m going …’

I spoke to a friend who said: ‘I wonder if we messed it up for ourselves, having such a good time when we were young.’

We are each of our age. We share a culture, whether The Clangers, or Withnail, or ‘Voodoo Ray’. Our heroes are communal, our references the same. Everyone has their own story, but it’s shaped by the time in which it’s told.

I’ve always enjoyed being part of something bigger. In the late 80s, I believed in rave and the power of the collective. Even now I like crowds, especially when music is playing; I love gigs, clubbing, festivals, marches, football matches, firework displays. I’m not mad about the hassle of getting to those places, but once I’m there, I’m fully in. As long as it isn’t too mediated, so that you can feel in and of an experience or an audience, so you are there, singly, but also consumed within a whole other entity, the crowd. The crowd has its own emotions, its own rhythm.

It’s good to lose yourself in that. I find it comforting to feel as others do, to share a moment; to know that I’m unique, but not that special. I like to know that what I’m going through, while personal to me, is also part of a pattern.

I thought about the 90s. I was very social. Always out, usually with other people. Most of my twenties took place then, in that time when youth was celebrated, where youth culture came in from the side, where the mainstream was altered by the upstart outsiders. And we – me, my friends, the crowd of us all – felt the rush of it, the need for speed. There was an up-and-out head-fuck that we searched for, constantly. Was that still within us, even now? That weird hyperactivity, the hunt for the high, a hatred of slowing up? A desire to escape the mundane, to be busy and crazed with endorphins. Even now?

In the 90s, drugs were involved in this, of course, and I thought about the people I know who have continued their hedonism into their forties. There were others who waited until middle age to start what used to be called dabbling. Others had given up everything – no booze, no drugs – but seemed driven to find other highs, through exercise: running, cycling, triathlons. Or they turned their drug obsessiveness into a new delight in food. Tracking down the most exclusive, carefully sourced ingredients from an expert, then taking such trouble over the preparation and timing that the moment of ingestion dominated their whole week … I noticed that all the new gadgets had names like ecstasy tablets. The Spiralizer. The Thermomix. The Mirage. The Nutribullet, made by a company called the Magic Bullet.

If you were young in the 90s, how does that affect your middle age?

I tried to think about this as I got up in the mornings, laid the table, helped small limbs in and out of uniforms, checked homework. S was away a lot, at this time, and I was alone with the kids. That was okay. Once you’ve had a child, and that child goes to nursery, or school, or a child-minder, you become plugged into a system. I had numbers to call, in case my arrangements fell through. And F was still little. Until she started crawling, I took her to meetings, showed her off like a new handbag. She was a good distractor.

My thoughts came and went. They mostly turned into questions.

Music was one, of course. I don’t think I know anyone who doesn’t believe in music, in what it can do. I’m of a generation that knows that music can save your life, give your life meaning, express the inexpressible, alter your course. People came into nightclubs while on a train track to normality and left believing they could be anything they liked. Their minds were opened up to a different way of living, a new way to work. They rejected the norm, the factory job, the lawyer training. Freelance creativity was their way out.

But what does music mean when you’re older? How does freelance feel when you’ve reached your forties, when you’re in a position where other people – your children – are relying on your work being stable, on the regular pay cheque that comes in every month? The internet had changed most of the creative jobs: journalism, media, photography, books, film-making, acting, fashion, comedy, music. There were fewer jobs and they paid less. All the work that seemed like an escape when we were young wasn’t proving to be so now.

Music, creativity, community, getting out of it. These were more than the habits of a generation: they were – they are – our touchstones. They had been how we got through life, what we had used to help us negotiate its pitfalls and terrors. It could be that part of my midlife angst was concerned with whether the old ways – our old beliefs – were effective any more. And what I could do if they weren’t having the same effect. If they don’t work, if they make it worse, then what?

In Bristol I gave a talk at a Festival of Ideas. I wasn’t sure I had any ideas worth festivalizing, but as what I’d been thinking about was midlife, I talked about that. I brought up death maths, and expensive bikes, drinking too much, and mourning the rush, and middle-aged sex lives. I made jokes about spiralizers.

Afterwards, there were questions from the audience. One man in his early 40s put his hand up and said, ‘I still feel 22.’ (‘Feelings aren’t facts!’ I didn’t say.) He had recently bought a skateboard. He didn’t know whether to learn skateboarding or hammer the skateboard to the wall, as a decoration.

How can we make our minds, which insist that we’re still 22, match up with our bodies, which are twice that age? How do we get rid of the sense of having missed out? How can we stop worrying about looking silly, because of our age? What should we do with our old MA1 jackets, or 12-inch remixes, or twisted Levi’s jeans? Does it matter if we don’t like new pop music? Is it okay to go to all-nighters if we go with our kids? What if we haven’t had kids?

I did my best with the questions. But I hadn’t studied mindfulness or sociology. I’m not a self-help guru. I can never tell if a new moisturizer makes any difference at all to my wrinkles. I was uncertain about many things, including time and consciousness and whether my mood (which was upbeat) was due to the warmth of the hall or the peri-menopause.

I wondered, what is an adult? We stretch our youth so far, so tight. We pull it up over our ageing bodies, like a pair of Lycra tights. We all do it to a certain extent, and yet we’re cruel to those who seem to hold on too hard for too long. We laugh about MAMILS (middle-aged men in Lycra) and cougars (middle-aged women sleeping with younger men). We mock women who have Botox and surgery, even as we urge them to stay as young-looking as they can. We giggle at dad-dancing, post up patronizing ‘Go on, my son!’ clips of grey-haired ravers on Facebook.

But it’s double standards. Because didn’t we, in our hearts, believe that youth is better than middle age? I think we did. I think we do. And our youthful ideals were clashing with our ideas of adulthood. There was a fight going on, inside and out. We take our children to festivals and get more trashed than they do.

‘What do you do in nightclubs?’ asked P. ‘I know you dance, but how long for? Can you choose the music? Why does everyone drink alcohol if it makes them ill?’

P once had a severe dancing-and-sugar comedown after a wedding. He danced for hours, fuelled on Coca-Cola and sweets. In the morning, he woke, white as a sheet, was sick, and had to go back to bed. He actually said, ‘I’m never doing that again, Mum. Never.’ His hangover was textbook, even though he didn’t drink.

I was great in nightclubs, but what did that qualify me for now? Could I continue with what I did – writing about popular culture, especially music – now that I was twice the age of those I talk to? A music writer. A critic. These jobs are as old-fashioned as being a miner, and as destined for redundancy. That’s a proper hangover.

Anyway, weren’t clubs partly about fancying people? I seemed to have a shifting sense of who I am. If you’re settled in a relationship, what does that mean? How does middle age affect your idea of love, of sex, of faithfulness? What about money? Not only did I know many people who earned a lot more than me, money, in general, seemed to have changed its meaning.

And what of the shallower stuff? How I looked. What my body could do, how it worked. My blood still pumped, I still bled. Did my body bleed as it used to?

Gradually, gradually, in between the bubbling, same-old rigmarole of everyday life, I came up with a plan. I would look back for a short time. (What’s the phrase? ‘Looking back is fine but it’s rude to stare.’) I would look back quickly, just long enough to investigate my prejudices and assumptions about adulthood. I would recall my twenties, check in on my thirties. There would be no beating myself up about wrong decisions, I would merely tell the tale. And then, I would arrive at my forties and I would look at that. At this middle decade, between the old age of youth and the youth of old age.

I would think about what I looked like. What my body can do. What marriage means, what happens when it changes over time. Work, and how our 90s’ assumptions might affect how we work now. Money. Money, which leads to jealousy. Anger, and patience, how they grow or die.

How children impact on your life in the everyday. Not the love – the love is assumed, we know the love – but what having children means for those who care for them, the routine of them, the stability. Parents. Family.

And death, I suppose. Time. The time left.

If I couldn’t tie these subjects down, catch them, skewer them with a ready pin for labelling and exhibition, then at least I could watch them fly. I could marvel at their existence. I might even see them settle (from the corner of my eye), and then I might glimpse their colours.