Читать книгу Out of Time - Miranda Sawyer, Miranda Sawyer - Страница 8

2. Adult-ish

ОглавлениеJanuary is always a bastard. Not only because it’s January, but because it’s my birthday, on the 7th. Exactly one week after New Year’s Eve, two weeks after Christmas Eve, when nobody wants to go out, or drink alcohol, or spend money, or see anyone they know well ever again, other than to tell them precisely what they think of them and their crappy idea of a gift or a joke or a long-term partner. S has used up all his present ideas for me over Christmas. And even if I do celebrate my birthday, the next day when I wake up, guess what? It’s still January.

But, you know, the kids love a birthday. They love giggling outside our bedroom door and then sneaking up to the bed with all the noiseless subtlety of piglets in mining boots. They love nudging each other – ‘You go, go on, one, two, three’ – before shouting, ‘HAPPY BIRTHDAY, MUM,’ and singing the birthday song and its coda: ‘How old are you now? How old are you now? How old are you NO-OW? How old are you now?’ They know the answer. Those birthday bumps would break your back.

Downstairs, on the kitchen table, my array of presents is minimalist. A card from my mum. A printout of a photo of the four of us from S, with a promise to ‘buy you something later’. Two packets of Haribo Tangfastics, my favourite sweets, from P, wrapped wonkily in Christmas paper. Not exactly bumper. But you know what? It’s fine.

I take the kids to school and F tells everyone it’s my birthday, and my age. This is also fine. I’m not going to start lying about it. How old am I no-ow? I am 44. I am 45. Or 46, 47, 48. Not much has changed in the past few years. I am an adult. Whatever that is.

I watch P as we walk to school. Though I often forget how old I am, and when I remember it pulls me up short, he is of an age when every birthday is vital, when how many years (months, days) you’ve lived add up to power. When two years’ age difference is a chasm, an insurmountable status gap. Another small boy, a head taller than my son, just another kid to me, is as thrillingly attractive and powerful to P as a pop star. He keeps trying to play football with the older boys. He trots faster to catch up with them. I can see them tolerating his breathless jokes, bearing his presence, but only just.

P’s birthday parties involve football, usually; sometimes the cinema or Laser Quest. What did I do when I was his age? How about older? 15? I can remember my 17th birthday (in a Scout hall) and my 21st party (above a pub) and my 30th, and my 40th, just a few years ago. My 40th birthday party was very like my 30th. The main difference was that when a stranger offered me ecstasy, I didn’t take it.

I don’t want a party like that now. I’m not sure why. Some time over the past few years I lost the desire to be the centre of attention and the stamina required for all the organizational palaver. I wouldn’t mind a party in the summer, maybe, with champagne cocktails and up-and-at-’em music, around a heated open-air swimming pool. A barbecue. Nicely dressed young people topping up drinks. In Los Angeles.

But in January, in London, in an expensive, cramped, roped-off area of a pub that you have to vacate at 11 p.m. or share with whichever punters decide to wander in? No, thanks. Maybe I’ll think differently when I’m 49 and a half.

Our idea of adulthood is formed by our youth. Adults were a puzzle to me when I was young. I looked at them and thought: How did they ever get married? Who could love these enormous, slow-moving creatures, with their pitted skin and springy hair? Their trousers hung loose over their flattened behinds. Their chipped, crumby teeth were like the last biscuits in the tin. When they were close, unpleasant smells leaked from hidden places. They talked a lot, in booming voices, about nothing important. They sat down. Then they stayed sitting down.

(‘Come on, Mum!’ says F, in frustration. ‘Stop talking! Let’s PLAY!’)

Not all adults were the same. I settled on my dad’s lap and put my hands on the outside of his hands. I tried to force them together, to make him clap. He’d resist, hold steady, until suddenly, he relaxed, and let my pushing win. Blapp! His big hands, cupped, made the most impressive noise I’d ever heard. A gunshot, a crack that split the air, indoors or out. I used to try to copy him. But the Dad Power Clap cannot be made by the young. Only dads, with their dad hands, can create such thunder.

I liked my dad’s smell. He smelt of nothing much, Swarfega sometimes, toast sometimes, talc. He didn’t wear aftershave. My mum didn’t wear perfume. She had a bottle of Chanel No 5, which I played with, but the liquid was orange, the scent was off. Sometimes, she smoked in the car on the way from work and her clothes smelt, not like fire, but chemical, metallic. She hid her cigarettes from us in her handbag. ‘Death sticks’, some people called them. I took them one by one, from the golden box, examined them, slit them open to scrutinize the curling tobacco slivers. Death looked a lot like wood shavings.

She stood in front of me and my brother and said, ‘Look, my thighs join all the way up, too.’ This was to my brother. He was weird about his legs, because mine were a different shape, and he was younger and wanted to be like me. I knew it didn’t matter – who cared what your legs looked like? It was whether you could run fast that was important – but it was another reason to lord over him. I liked to emphasize our differences, though we were very similar. Our bodies were small and strong. We hung them upside-down from anything.

My mum wore no make-up. Her cosmetics bag contained one brown mascara, old and dried up, one lipstick and some shiny blue eye shadow. She rarely used any of them. Not when she went to work, as a secondary-school teacher, not when she saw friends. Only on special birthdays, when we went out to a restaurant to sit quietly and worry over cutlery selection. She wore trousers, no heels. In heels, she towered over my dad.

Neither of my parents put much effort into their appearance – odd, when we lived in a suburb that judged you by what you wore when you put out the bins – but, still, I thought they looked good. Handsome, rather than cute. Slightly 1960s, even in the 70s and 80s. My mum changed her hairstyle a lot: in the space of five years, she had a long orangey bob; a cap of sleek, dark curls; a blonde Purdey-style crop. She wore blouses that looked like shirts, nothing girly, no florals.

And, even when my dad got burnt in the sun, when his stomach reddened in stripes where the skin had folded as he’d sat reading, I thought he was fantastic. (His feet burnt too, so after one day of holiday he wore socks and sandals, like the university lecturer he was.) He was great at sport: football, cricket, throwing and catching, crazy golf, anything to do with a ball. Also, card games, building dens, drawing. He worked out the Rubik’s Cube in a matter of minutes. He could skim a stone so it bounced seven times. He had a side parting and his hair flopped over his right eye.

When I was P’s age, my mum was 37, my dad 40. When I think of my parents, I think of them then, and a little older, as I grew into my teens. I see them in their middle age. Was that their prime? It seemed so, to me.

Now, their elderliness comes as a surprise. How careful they are as they get out of the car, the time it takes, the probing for the pavement with extended foot, how they grip the door frame to pull themselves up and out. Every time they come to stay, and I notice their slowed movements, I have to readjust my image of them, overlay it with the reality. They have changed shape. My dad, once slim as a reed, is rounder. My mum has grown thinner. Their hair, their teeth, all different. They have the accessories of the senior citizen. Age-related discount cards. Spectacles: off-the-shelf, from Boots. Mouth plates, with odd teeth on them, like sparse standing stones. Hearing aids. Sudoku.

Despite all this, they are not as old to me as they once were. When I was a child, when my parents were younger than I am now, they were ancient. But now the gulf is not as wide.

I knew that my parents – my adults – were not like other grown-ups. They were special because they were mine. They loved me, as I loved them. Though I couldn’t truly fathom how they could love each other – not as a separate unit, not without us children to mediate, to inspire passion. I loved my parents in a devoted but patronizing way, convinced that nobody else could want such battered specimens. They were like old teddies. The only people who valued them were those who’d cared for them for a long time.

Other children’s adults were bewildering. Their nostrils were enormous – you could see the hairs in there, sometimes the bogeys. They breathed at you and asked you questions to which there were no proper answers, such as: Haven’t you grown? How’s school? (I do this now.)

They told you off for different faults from the ones your parents chose. Leave your shoes out the back! Don’t blow bubbles in your drink! Use a teaspoon for the sugar! The women wore make-up that made their faces all slidy, the men dressed exclusively in shades of mud-brown, from shoes to spectacle frames. Those slurpy noises they made when they drank their tea, the ‘oof’ when they sat down, said in a comedy voice, to get a giggle. How old were they? Who knew? 25? 42? 117?

At junior school, I loved a few teachers. Mr Buckley, who had a beard and liked a laugh. Miss Braben, who taught us stories. Matronly, shaped like a peg doll, with a shelf bosom and padded hips. Once, she stopped the class to tell us all to look through the window. There was a horse, somehow free to roam south Manchester, galloping past the school, sweaty and wild-eyed. Its enormous head flicked and twisted through the air, its legs glistened; an astonishing sight. We stared. Then we went back to I Am David.

But most teachers – most adults – were scary. Horror-story characters. The headmaster resembled a giant winged insect, striding around in his billowing black gown, leading us in succinct, reasonable prayer at assembly: ‘Dear Lord, we ask you to grant us … a GOOD day … Amen.’ When I went to senior school, there were science teachers with stains on their shirts; a maths teacher who smelt so rank that, when you asked a question, you held your breath as he talked you through what you should be doing. He crouched down to check we understood, kind, careful man that he was; we let out our breath dramatically when he moved on.

One teacher had an enormous pus-filled spot that moved daily from the side of his nose to the space between his eyebrows. One, who taught sports, a woman, made sexy jokes that we didn’t quite understand. One, a Latin teacher, eccentric and funny, was so well-known as a pervert that whenever he told me, or any of my gang of five girlfriends, to stay behind for being naughty, another of us remained too. We didn’t even talk about it, just made sure there were two of us. We backed around the desks as he advanced.

Though I liked many of them – the Latin teacher was one of my favourites – they were all, fundamentally, repellent. Coarse, bloated, unsmooth, hairy. But it wasn’t just their looks. They were Other, a different species from me and my friends, and we were happy with that. I was an anti-adult bigot. I believed in child/grown-up apartheid. I didn’t want to think of them as anything other than alien. I didn’t want them to think of me at all.

Even as I grew into my early twenties, adults remained off-putting. They operated outside us, in their different world. We were in our own gated community, within theirs. This suited us. We looked inwards, we liked our prison. But sometimes our elders would crash across the invisible fences. It was always uninvited, always a surprise.

During the summer I was 21, I worked for a few weeks teaching English as a foreign language in a residential school in Kent. The school was like a stately home, and we taught children from all lands: Italy, Japan, Israel, what was then Yugoslavia. Any child whose rich parents chose to go off shopping in London rather than risk a week’s holiday with their offspring.

At the end of the three weeks, there was a staff party. All of us teachers got drunk; I jumped, fully clothed, into the swimming pool. In the corridor by the kitchens, another teacher, our team leader, a man in his forties, said something irrelevant and plonked his lips on mine. He had a moustache. It was like having your mouth explored by an adventurous damp nailbrush – as sexy as that.

That same summer, I used my TEFL money, plus cash I’d earned as a cleaner, to get a train to Barcelona with three girlfriends. We hung out on the Ramblas, at a square where tourists mingled with black-clad heroin addicts. Another middle-aged man with another moustache: this one grabbed me on the way to some restaurant toilets.

Why did drunk older men think that snogging was an inevitable consequence of having fun? The way they kissed wasn’t sexual, but controlling. It was as though they clamped their mouths on yours to shut you up. But we hadn’t even noticed them before they talked to us.

Adults are outsiders in young people’s real lives, until we make ourselves known, by forcing our way in, by telling them what to do. Until we blunder over, unwelcome gate-crashers at the party.

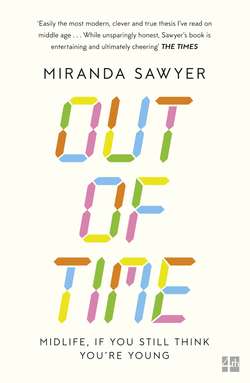

On the front of a magazine, I see this: ‘Adults Suck and Then You Are One’. A slogan on a jumper. I would like to own this jumper.

Because now I am an adult – one of those inappropriate, frightening, physically bizarre people. I’m quite good at talking to kids, but isn’t there something creepy about that? There’s no hiding my sagging skin, my English teeth. I don’t stick my tongue down anyone’s throat unless I’m married to them. But when I grab my son’s friends as a joke, pretend to chase them round the kitchen for a kiss, COME HERE, LITTLE BOY, MWAH MWAH MWAH, a lumbering dinosaur great-aunt, I wonder: Is this funny or am I properly freaking them out?

What is it about adulthood that is still so unappealing? I don’t want to go back to school, with its bewildering, kid-enforced social rules, so rigid they couldn’t be broken, so fluid they changed every day. But I don’t want to be like the grown-ups I grew up with. So … separate, in such an unappealing world. Dull. Rule-bound. Constricted by paying bills and by convention. Even in what you wore: no one had many clothes then, and what adults wore was practical, designed not to stand out, except on special occasions. Despite the outré flamboyance of some grown-ups’ going-out wear, their working clothes were joyless: suits and sensible skirts, overalls, pinnies.

Adults, teenagers and children were all demarcated when I was young. But something happened between then and now. Children got older (they gained status within the family) and parents got younger – if not actually younger, then in the way they looked, their approach to life. Everyone’s a teenager now, and for a lot longer. The teenager has become revered, absorbed into our normal. Parents and their older children go to the same places to eat, to dance, to hang out. They listen to the same music.

Those teenage tenets of non-conformity, of staying true to your beliefs, rather than compromising them for an easy life, of rebelling against rules that you know are worthless and mean nothing … These are now the attitudes that we all respect. Even in adults, even in politicians. Authenticity is all, and authenticity means an anti-establishment, punching-up strength of character. Tedious, conventional adulthood, that refuge of phoneys and scoundrels, of lecherous old men with moustaches, of the boring, the selfish, the power-hungry – that doesn’t cut it any more. We have extended youth so far that its values have become universal and nobody interesting can ever fully grow up.