Читать книгу Contempory Netsuke - Miriam Kinsey - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPhotographers' Notes

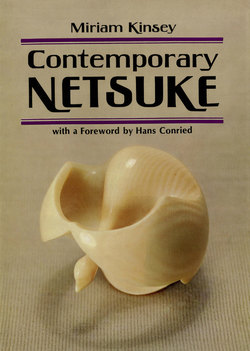

SEVERAL years ago when Mrs. Miriam Kinsey contacted me and requested that I do some photographic work for a book she was compiling on contemporary Japanese netsuke, my countenance must have divulged my inner reaction. I felt that anyone so involved with “new" netsuke must be a “naive foreigner," unaware of the beauty of traditional Japanese arts and of “old" netsuke carvings. While watching Mrs. Kinsey speak, I immediately recognized the deep attachment she had for the little netsuke objects she held in her hands. To her they were like little living objects. I also noticed that she had respect and admiration for the contemporary ivory and wood carvers, since she spoke about them as dear friends. Needless to say, I accepted the photographic task because I felt a kindred spirit with Mrs. Kinsey and also because I was delighted to face the creative and technical challenge the project offered me.

For the past thirty years, I have been “a fellow crazy about Oriental bowls, pots, and paintings" and my life has revolved around them. During the past ten years, thanks to Mrs. Kinsey, I have become acquainted with the names of most of the outstanding contemporary netsuke carvers of Japan, and I have become truly familiar, through visual and tactile experiences, with the “new" netsuke. And, surprisingly, I have found a great many of them truly outstanding as honest expressions of creativity on the part of the skilled artist-craftsmen. In many cases, I must admit that from the skill and artistic integrity of some of the living carvers have come “new” netsuke masterpieces just as great as, or even greater than, the masterpieces of the past.

Before pointing my large 4-by-5 camera lens and the lights toward each netsuke, I have made it a habit to hold the gentle object in my hands and to “communicate” with it through my fingertips, with my eyes, and even with words. Would you be surprised if I told you that each netsuke has taken the trouble to relate something to me? Some messages have come through in soft whispers while others were loud bellows. I have learned, not only through the netsuke but also through handling other art objects, that each item is a crystallized formation of the love that possessed its creator. Without this deep devotion to one's art or craft and to the objects produced, how can one expect these little items to survive the gigantic waves of changes of the times?

Each object has given me a challenge to show it in its most advantageous pose and to make certain that I can still help maintain the “life spirit" of the netsuke. If I have succeeded in capturing the spirit and form of the netsuke even to a small degree, I must first credit the netsuke carvers for their originality and Mrs. Kinsey for her patience, kindness, and trust.

TOMO-O OGITA

Los Angeles, California

IN YEARS past, many craftsmen in Japan were called "masters" (meijin). However, there are only a few people of this type left today—people whose lives revolve around one skill or one craft, like the metalsmith who can produce oxidized silver. In some cases, there may be only one person, or perhaps no one, left in all of Japan to carry on a specific traditional craft.

The contemporary artists of Japan who are shown in the pages of this book are still quietly working in the authentic tradition of their craft. These netsuke carvers are people who have their art truly in their hands and are manifesting the skills of the traditional meijin.

It is my thought that the hands of the craftsmen or the netsuke carvers are precious creative instruments. With their skilled hands, the raw wood or ivory is soon transformed into something new. We are told that the value of the item starts from that point.

A work created in earlier years is passed on to someone in the next generation. Based on the way of life of that time, as well as the thoughts given to the work over a long period of time, changes will be reflected in the color and form of the work. Tradition changes with the life and times of the people and readily shows how strongly the beauty of the object influences our life and livelihood.

The hands that have worked to make things eventually discover “creativity,” and the created objects, each with special characteristics, bring joy to our senses. There in front of our eyes we do not view a manufactured item but an object made by the hands of man. Machines cannot produce such work. An object made by the skilled hands of an-artist gives aesthetic joy to the beholder and also imparts the realization that one is gazing upon a “true thing."

Fortunately, there are still about twenty first-rank netsuke carvers in the Tokyo area and several in the Kyoto region. By casting light upon these quiet, talented, and dedicated artists, it will be possible to have a larger audience that truly understands the meaning and value of "things made by hand."

TSUNE SUGIMURA

Tokyo, Japan